At the Update Refresher, one presentation was dedicated to COPD and emphysema. It was shown which questions should already be clarified in the family practice and how the patient can be supported specifically pharmacologically and with lifestyle measures. If emphysema patients remain symptomatic despite optimal medical care, lung volume reduction is a possible treatment option. Various endoscopic procedures have become established here in recent years.

Six questions in particular are important for the primary care physician in COPD, according to Lukas Schlatter, MD, Pulmonary Practice Wohlen:

- Does my patient really have COPD?

- If yes, what is the phenotype?

- Does my patient (still) smoke?

- Is he moving?

- Does he inhale? And if so, with which preparation and how?

- Does it need the addition of a pulmonologist?

To clarify the first question, it is important to make an accurate differential diagnosis, which can be quite challenging. The leading findings of COPD – cough, sputum, obstruction, dyspnea, and O2 deficiency – open up a large field of possible clinical pictures. Examples include bronchial asthma, bronchiectasis, or heart failure for cough, sputum, and obstruction. The latter is also an important differential diagnosis in dyspnea and O2 deficiency, as are pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), coronary artery disease, and ventilatory disorders.

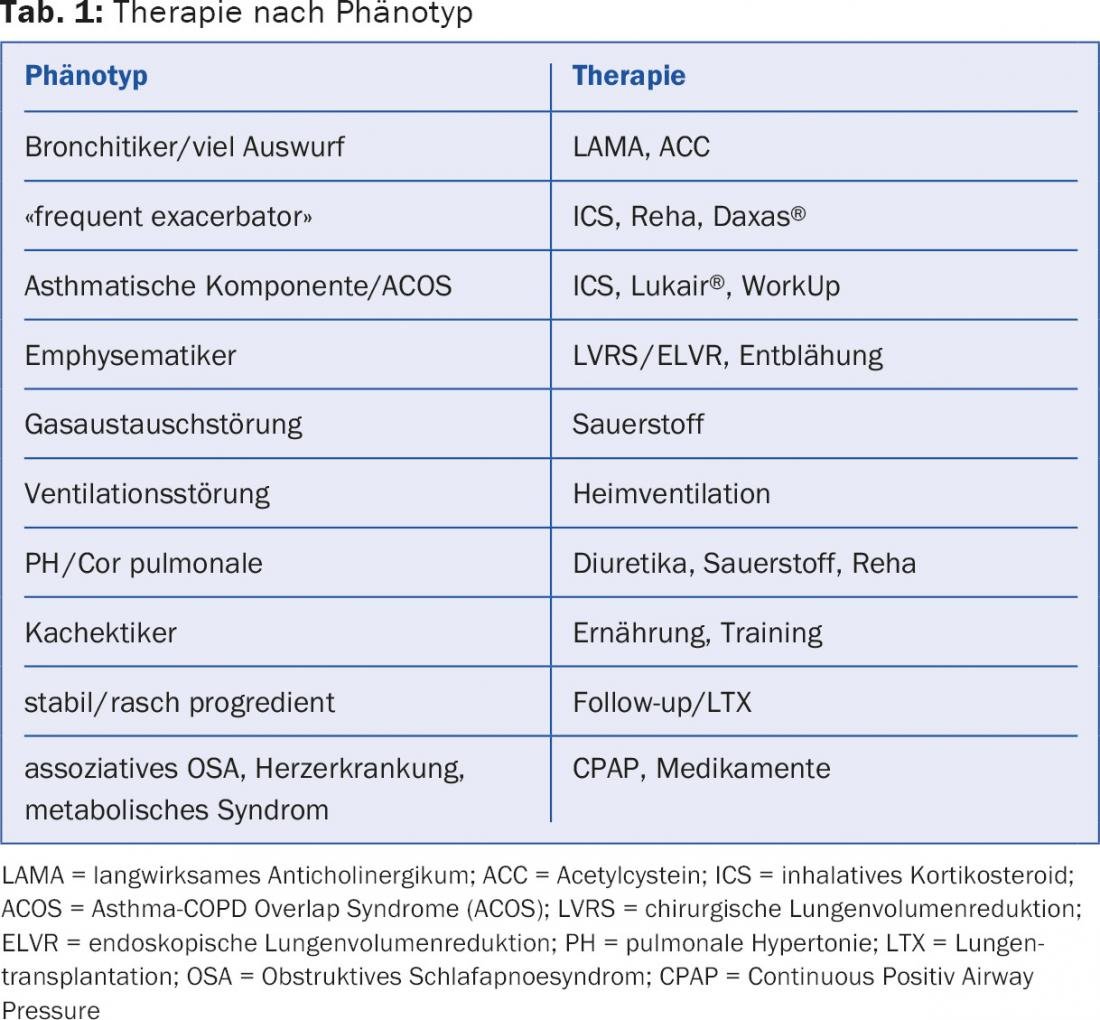

Depending on the phenotype, different active substances and principles are used. Table 1 provides an overview of this.

Smoking cessation and exercise useful at any time

“Quitting smoking not only reduces the risk of developing COPD in the first place, it is also the most effective measure for all stages of the disease that has already set in,” the speaker said. “This slows FEV1 decline and significantly reduces mortality, both that of COPD itself and associated comorbidities [1–3].” It is important to specifically address smoking cessation in the consultation. Minimal medical consultation (“Do you smoke? Have you considered quitting?”) already achieves significantly higher abstinence rates than standard consultation, according to one study [4]. Even more effective is intensive counseling, e.g., via the so-called “step model of behavior change” according to Prochaska et al. However, the greatest effect in terms of abstinence is achieved by intensive counseling combined with pharmacotherapy (e.g. Zyban® or Champix®). The impressive effect of quitting smoking can be complemented by physical activity. Again, the evidence is clear: exercise reduces mortality and exacerbation risk [5–7].

Inhalativa

The large variety of inhalatives does not make treatment decisions easy. According to the new multidimensional classification of COPD (so-called ABCD rule), different first-line therapies are recommended depending on the severity:

- A: short-acting anticholinergic if needed or short-acting β-2-agonist if needed.

- B: long-acting anticholinergic (LAMA) or long-acting β-2-agonist (LABA).

- C: inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) + long-acting β-2-agonist (LABA) or long-acting anticholinergic (LAMA).

- D: inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) + long-acting β-2-agonist (LABA) or long-acting anticholinergic (LAMA).

“The many alternative options (in first- and second-line) make it difficult to choose the best therapy. A possible way out is the individual approach as shown in Table 1 ,” Dr. Schlatter advised.

Does the patient need a pulmonologist?

The following are easily accomplished in the family practice setting: diagnose, assess severity, stop smoking, establish inhalants, vaccinate, promote activity, and follow-up. Optimally, the symptoms can be controlled, exacerbations can be avoided and the course stabilized. Quality of life and performance increase.

However, if the patient is still unwell after all these measures, a pneumological council should be considered in any case. This will allow specific further investigations and therapies (e.g. emphysema therapy, transplantation).

Treatment of emphysema

Peter Grendelmeier, MD, Senior Physician, Pneumology, University Hospital Basel, spoke about one of these therapies, namely lung volume reduction. The main patients eligible for this therapy are the so-called “pink puffers” – typically underweight emphysema patients with significant dyspnea and dry irritable cough. “What we’re looking for are signs of over-inflation,” Dr. Grendelmeier said. In body plethysmography, this is indicated by an increased residual volume (RV) or an increased ratio of residual volume to total lung capacity (TLC): In normal lungs, the vital capacity is about 65% and the residual volume is 35% – in hyperinflated lungs, the values can be about 50% to 50%.

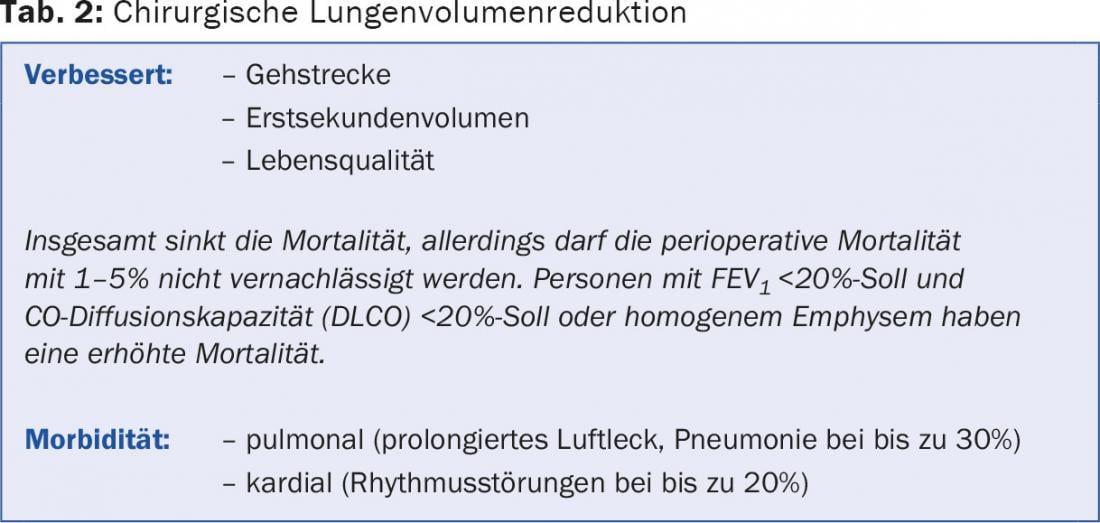

Surgical lung volume reduction: the large NETT trial [8] in 2003 showed that surgical lung volume reduction specifically benefited those patients who had predominantly upper lobe emphysema and low baseline exercise capacity. Here, the mortality risk was significantly reduced. In contrast, individuals operated on without upper lobe emphysema and with high exercise capacity had a significantly higher mortality rate than the comparison group with drug therapy. Specifically, individuals with FEV1 <20% target and CO diffusing capacity (DLCO) <20% target or homogeneous emphysema also performed significantly worse with surgery than the non-operated control group. Opportunities and risks of surgical lung volume reduction are shown in Table 2.

Endoscopic lung volume reduction: with new techniques such as the valves, coils or stents, the question arose whether a scalpel is really needed for lung volume reduction or whether an endoscope is sufficient. In the field of coils, a 2012 study [9] showed that the 6-minute walk test and disease-related quality of life in particular could be significantly improved. Adverse events possibly associated with the procedure or device included pneumothorax, pneumonia, exacerbations, chest pain, and (most commonly) mild hemoptysis <5 ml by 30 days after surgery. After this month, pneumonia and COPD exacerbations were still mainly found. Side effects were reversible under standard care measures.

Selection of patients

According to Dr. Grendelmeier, the decision on the possibility and type of lung volume reduction should be made on an interdisciplinary basis. The following questions, for example, can be used to select patients:

- Is the patient being anticoagulated?

- Is there collateral ventilation?

- What comorbidities exist?

- For example, is pulmonary hypertension present?

- Is it a st. n. surgical lung volume reduction?

- Is it severe emphysema with missing tissue?

- Is it homogeneous emphysema?

- What about the reversibility of the therapy?

Depending on whether the answer to these questions is yes or no, surgical lung volume reduction, endoscopic lung volume reduction, or no lung volume reduction is performed. “Very fundamentally, reduction should be thought of in ‘pink puffers’ after maximal or optimal therapy (pharmacological, home oxygen, rehabilitation) who have a residual volume of >175% target and COPD GOLD stage III/IV,” the speaker concluded.

Source: “Diagnosis and Treatment Options for COPD and Pulmonary Emphysema,” lecture at Update Refresher Internal Medicine, June 16-20, 2015, Zurich.

Literature:

- Anthonisen NR, et al: Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA 1994 Nov 16; 272(19): 1497-1505.

- Anthonisen NR1, Connett JE, Murray RP: Smoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002 Sep 1; 166(5): 675-679.

- Anthonisen NR, et al: The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 2005 Feb 15; 142(4): 233-239.

- Hoogendoorn M, et al: Long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in patients with COPD. Thorax 2010 Aug; 65(8): 711-718.

- Garcia-Aymerich J, et al: Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax 2006 Sep; 61(9): 772-778.

- Waschki B, et al: Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest 2011 Aug; 140(2): 331-342.

- Gimeno-Santos E, et al: Determinants and outcomes of physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Thorax 2014 Aug; 69(8): 731-739.

- Fishman A, et al: A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med 2003 May 22; 348(21): 2059-2073.

- Slebos DJ, et al: Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction coil treatment of patients with severe heterogeneous emphysema. Chest 2012 Sep; 142(3): 574-582.

FAMILY DOCTOR PRACTICE 2015; 10(10): 33-25