Raw or insufficiently cooked food can transmit pathogens. The origin of the food and the method of preparation are therefore important pieces of information. However, with a few precautions, you can enjoy typical and local specialties.

“Fools tour the museums in foreign lands, wise men go to the taverns” (Erich Kästner).

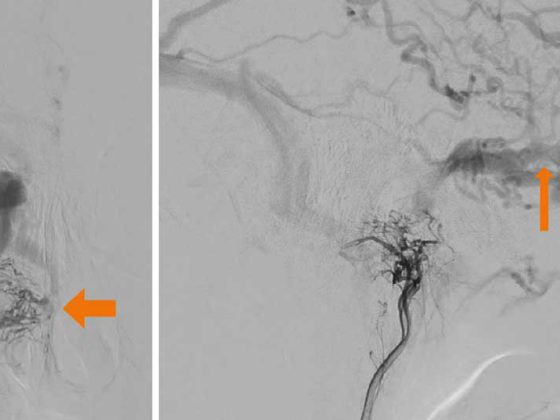

Those who travel would also like to gain culinary experience and try typical dishes of the country (Fig.1). From the medical side, we give the typical advice “cook it, boil it, peel it or leave it” for this, in order to generally prevent traveler’s diarrhea in countries with lower hygiene standards, which is caused by viruses, bacteria and less frequently by parasites. This advice sounds simple and convincing, but it is almost never implemented. For example, 90% of all travelers still eat fresh salad on the road. The incidence of traveler’s diarrhea is 10-30% in the first two weeks, depending on the region [1].

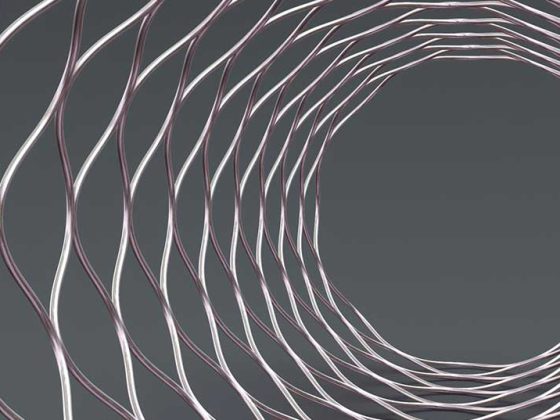

In addition to diarrhea, systemic complications may develop. For example, Figure 2 shows an amoebic liver abscess that did not manifest until approximately one month after the actual diarrhea episode. Hepatitis A and hepatitis E infections are also important. These non-chronic hepatitides are endemic in most travel destinations (including the Mediterranean region!) and can in principle be transmitted by all types of food or drink [2,3]. Hepatitis A can be prevented by vaccination, hepatitis E vaccination is approved in certain countries, but not yet in Switzerland.

However, this article does not focus on the classic traveler’s diarrhea (“Delhi belly”), but is intended to point out specific infectious risks based on individual dishes.

Cheese and dairy products

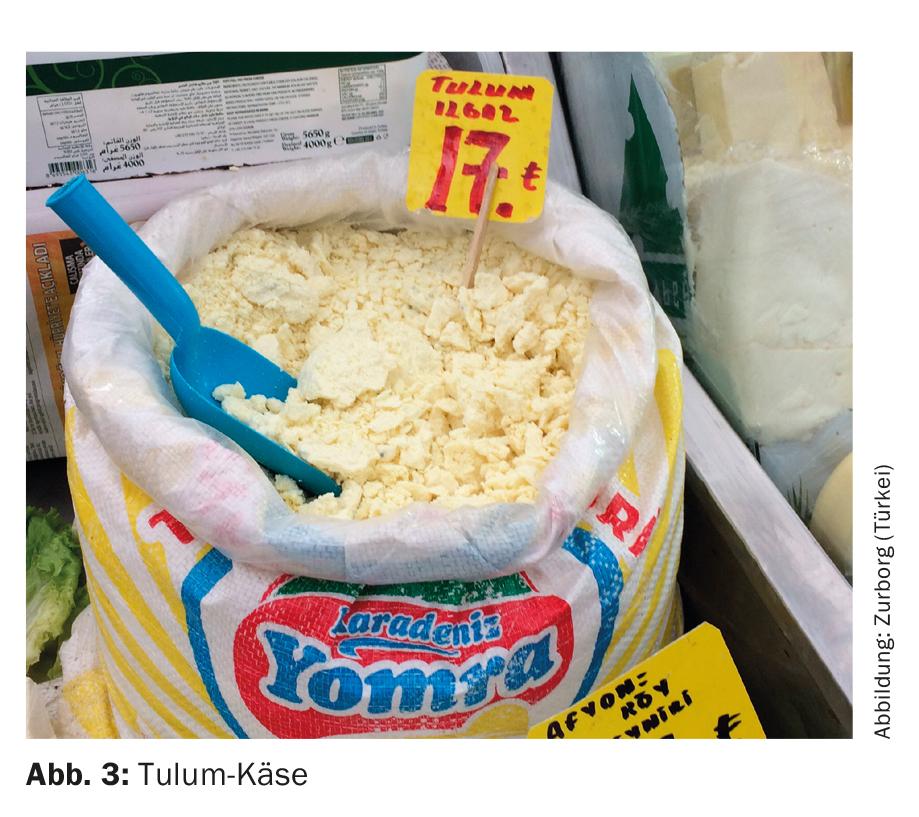

Especially as a traveler from Switzerland, one would naturally like to make a cheese comparison. But this carries risks in many countries, as cheese is partly made from unpasteurized milk. For example, North Indian fresh cheese “Paneer” can also be made from unpasteurized milk, as can “Tulum” (Fig. 3) or “Beyaz peynir” from Turkey. Consumption of raw milk or raw milk cheese, among other things, can result in brucellosis. Brucellosis is the most common bacterial zoonosis worldwide, with 500,000 new cases annually [4]. The infection is caused by Gram-negative bacteria of the genus Brucella . Human pathogens are B. melitensis (camel, sheep, goat brucellosis, known as Malta fever in humans), B. suis (porcine brucellosis), B. abortus (bovine brucellosis), and B. canis (canine brucellosis), with B. melitensis being the most common worldwide. The clinical spectrum is broad, ranging from subclinical to acute febrile courses to chronic disease. Since it is a systemic disease, all organs can be affected. In the chronic course, spondylodiscitis or arthritis as well as endocarditis are possible; however, lymph nodes, liver or spleen are frequently also affected due to dissemination in the reticuloendothelial tissue.

Previously, South America, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean region had high prevalence. In many regions, improved sanitary conditions and surveillance of livestock have led to control of human brucellosis, changing the epidemiology over the past 20 years. In South America, the incidence has decreased significantly. In contrast, there was an increase in incidence in Central Asia. Furthermore, the Middle East and North Africa are strongly affected. The worldwide incidence of brucellosis can be found in reference [4].

In Saudi Arabia or the Middle East, fresh camel or goat milk is often offered on the street. Fresh camel milk in particular is considered a delicacy. Desserts made from raw milk such as “Kunafa” are also popular. Just the aspect that the milk is quite fresh is a fallacy. Travelers need to be educated that brucella can persist in milk for several days, multiply in fresh goat or sheep cheese, be detected in ice cream for up to four weeks, and in butter for up to five months [5]. Pasteurization kills the bacteria, so only products made from pasteurized milk should be eaten.

Fish

Fish dishes are often on the menu of travelers in subtropical or tropical areas. Here you need to pay attention not only to the preparation, but also the type of fish. Especially eating predatory fish can result in fish poisoning. The most common fish poisoning is ciguatera, which is caused by ciguatoxin. There are over 50,000 cases worldwide each year. In travelers to endemic areas, occurrence is suspected in up to 3% of those exposed. Poisoning occurs through the consumption of predatory fish, which accumulate toxic metabolic end products of marine protozoa, dinoflagellates (Gambierdiscus toxicus), in their tissues through the food chain. The protozoa live on algae of coral reefs and are ingested by herbivorous fish, which in turn are eaten by predatory fish. The lipophilic ciguatoxin is concentrated mainly in the liver, intestine and head of predatory fish. The toxin is heat stable and is not destroyed when fish meals are prepared. The higher the fish in the food chain, the higher the risk that it contains ciguatoxin. Gastrointestinal symptoms occur within 5-24 hours when consuming predatory fish. Later, cardiovascular (hypotension, bradycardia), neurological (paresthesias, myalgias, dysesthesias), or neuropsychiatric (anxiety, depression) symptoms may occur. In most cases, the symptoms disappear after a few days. Rarely, neurologic symptoms persist for several months [6]. In total, about 200 species of fish can be carriers of the toxin, with reef predators such as barracuda, mackerel, snapper and grouper being particularly affected. Ciguatera occurs epidemically in subtropical and tropical coastal regions between 35° north and south latitude. It is particularly common in the Pacific, Indian Ocean and Caribbean. Since G. toxicus reproduces well especially on dead coral reefs, an increase of Ciguatera can be assumed despite progressive destruction of the reefs [7].

Not only marine fish, but also freshwater fish can pose a risk. For their consumption should take into account the method of preparation and the region. Thus, consumption of raw or inadequately cooked or fried fish, crustaceans, amphibians, or snails can result in gnathostomiasis or angiostrongyliasis. In both worm diseases, the human is a false host. Gnathostomiasis is most common in countries where a lot of raw fish is eaten. It is most prevalent in Southeast Asia and Japan, but in recent years there has also been an increase in disease in South America and Mexico. In addition, cases have been described in southern Africa. In particular, avoid eating sushi in endemic areas, where there are often no government controls on fishing and fish storage, and the sushi is often prepared from local, cheap freshwater fish. Gnathostoma spp . can also be transmitted by ceviche, a dish of raw fish marinated in lime, which is very popular in South America. The pathogens are killed by cooking as well as freezing food [8].

The disease is caused by ingestion of infectious larvae of Gnathostoma spp. that reside in cysts in the muscle meat of raw fish, shellfish, snails and other animals. Acute symptoms such as general malaise, fever, and gastrointestinal discomfort may occur within 24-48 hours. These symptoms are caused by the migration of larvae through the stomach or small intestine wall. Over the course of three to four weeks, the typical skin symptoms may appear: passive, itchy, subcutaneous swellings. Complicating matters, a visceral form may also develop as the larvae migrate through affected organs (liver, CNS, etc.). Gnathostomas are typically associated with marked eosinophilia.

Angiostrongylus spp. is mainly triggered by eating insufficiently cooked or raw mollusks, vegetables contaminated with snail mucus, or by ingesting other false hosts (such as crabs, freshwater shrimp). This roundworm is the most common cause of eosinophilic meningitis.

Other helminth infections that can be acquired by eating crustaceans or freshwater fish are the fish tapeworm (Diphyllobothrium latum) , which incidentally is also endemic in Swiss lakes, the Chinese (Clonorchis sinensis) or the Southeast Asian liver fluke (Opisthorchis viverrini).

Pork

In developing countries where pigs are kept for meat production and there are no meat inspections, infection by the porcine tapeworm Taenia solium is common. Humans can become infected in two ways. One is through the consumption of insufficiently cooked pork contaminated with fins. In the small intestine, these develop into the adult tapeworm, whose eggs are excreted in the stool (taeniosis). Infection with adult worms is usually asymptomatic. On the other hand, serious infection can result from ingestion of eggs in contaminated food. The eggs develop into larvae, which lodge as fins in tissues, especially muscle and brain. This corresponds to (neuro)cysticercosis. Thus, cysticercosis can also affect vegetarians. Neurocysticercosis is thought to cause up to 30% of new-onset epilepsies in adults worldwide [9]. As mentioned at the beginning, uncooked foods should therefore be avoided for this reason as well.

Take-Home Messages

- Raw or even insufficiently cooked, simmered or grilled food can transmit bacterial, viral or parasitic pathogens.

- The origin of the food and the method of preparation are therefore important pieces of information for the prevention of food-borne infectious diseases.

- There are few exceptions to this principle, e.g., ciguatoxin poisoning. Knowledge of local conditions is crucial here.

- Taking these (few) precautions into account, however, travelers should definitely try and enjoy local food and specialties!

Literature:

- Steffen R, et al: Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review. JAMA 2015; 313(1): 71-80.

- Aggarwal R, et al: Hepatitis A: epidemiology in resource-poor countries. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2015; 28(5): 488-496.

- Béguelin CF, et al: Hepatitis E. Swiss Medical Forum 2016; 16(24): 510-514.

- Pappas G, et al: The new global map of human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2006; 6(2): 91-99.

- Memish ZA, et al: Brucellosis and international travel. J Travel Med 2004; 11(1): 49-55.

- Friedman MA, et al: An Updated Review of Ciguatera Fish Poisoning: Clinical, Epidemiological, Environmental, and Public Health Management. Mar Drugs 2017; 15(3). pii: E72.

- Brunette GW (ed.): Centers for Disease Control, V.E.A.: Food Poisoning from Marine Toxins. The Yellow Book – CDC Health Information for International Travel 2016. Oxford University Press: Atlanta, Georgia, USA 2017.

- Herman JS, et al: Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22(3): 484-492.

- Garcia HH, et al: Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13(12): 1202-1215.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(6): 8-10