Acute abdomen is frequently encountered by the primary care physician. At this year’s SGIM Great Update in Interlaken, possibilities in diagnosis and therapy were presented. In elderly patients in particular, five potentially lethal diagnoses should be actively sought: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, perforations, pancreatitis, mesenteric ischemia, and obstruction.

Prof. Dr. med. Roland Bingisser from the emergency department at the University Hospital Basel opened his lecture with a casuistry: A 72-year-old man comes to the emergency department with increasing abdominal pain. He vomited twice between 2 and 4 a.m., seems a bit feverish and weak, but actually thinks the visit to the doctor is excessive. His vital signs are: Respiratory rate 22, pulse 90, blood pressure 120/60. “What would you do first?” was Prof. Bingisser’s question to the audience. “In any case, you should give the patient a good analgesic first, such as morphine 2 mg i.v., so do early analgesia.”

How to deal with acute abdomen?

Acute abdomen is defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by sudden severe abdominal pain requiring emergency treatment. The problem with this definition, however, is that it only captures a subset of patients who require emergency therapy. So specifically for older patients, it is not comprehensive.

“In general, analgesia should be given as early as and as judiciously as possible: Investigability is still ensured and diagnoses are therefore not missed more frequently. The outcome is comparable, but patients are significantly more satisfied with treatment than if early analgesia is dispensed with. The only problem is that 61% of older surgeons and 40% of young surgeons are still opposed to this acute therapy,” says Prof. Bingisser.

In addition, antibiotics should be given immediately if sepsis is suspected, and antibiotic prophylaxis is useful in appendicitis.

Diagnostically, the exact medical history (Tab. 1) and a detailed repetitive status are supplemented by a laboratory (blood count, CRP, lipase, blood glucose, lactate) and imaging, e.g. by means of abdominal X-ray, sonography as well as CT. If laboratory values are completely normal, surgery is seldom necessary, but it should be borne in mind, especially in older patients, that leukocytosis is less frequent. In terms of imaging, CT is superior, but expensive and radiant.

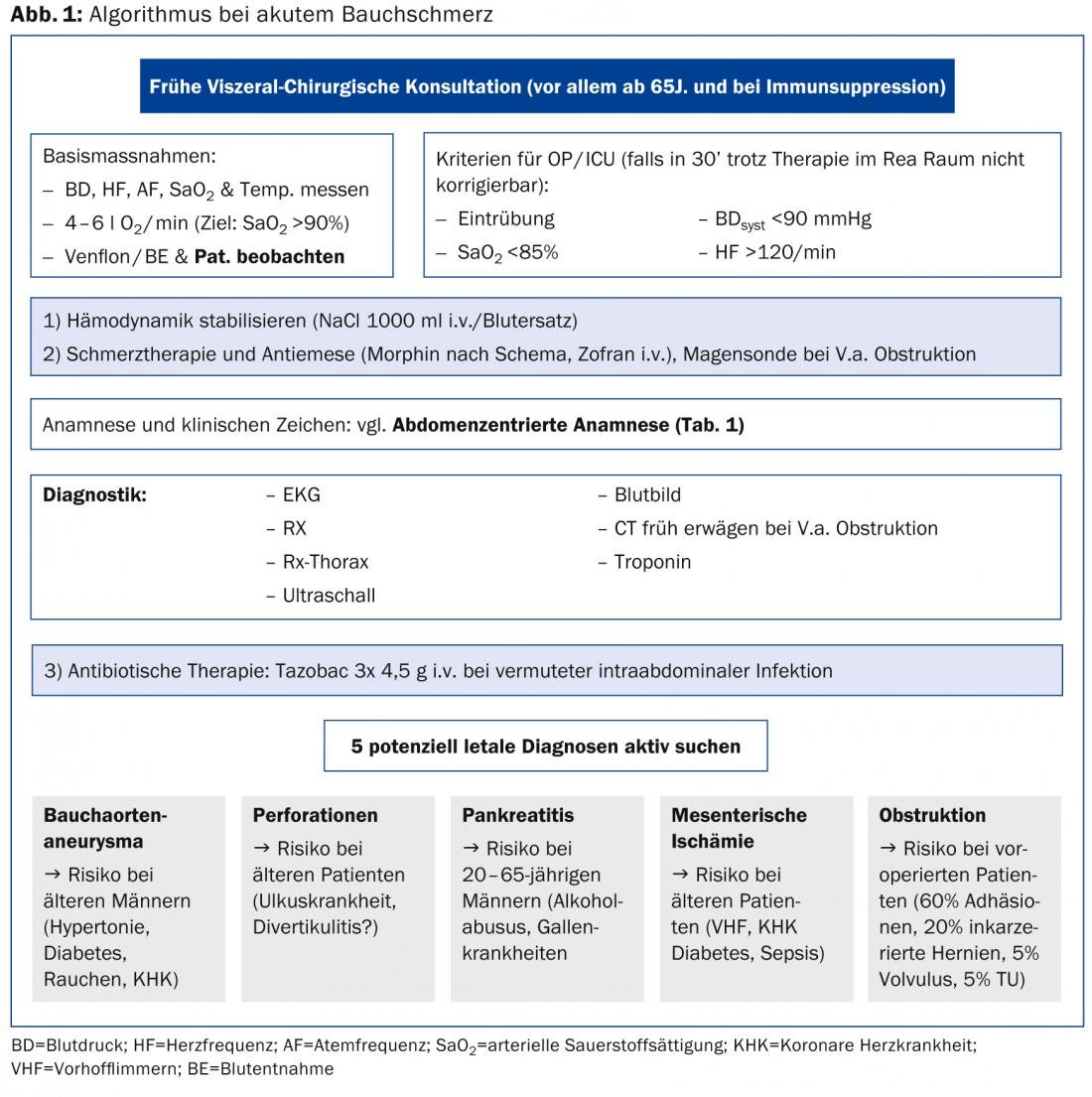

“Personally, I follow an algorithm in diagnosis and therapy (Fig. 1) . This also mentions the five most important potentially lethal diagnoses, which one should actively look for in any case. For older patients in particular, an increase in risk can be assumed in these areas. A plain radiograph of the abdomen is not necessary, as it was shown in the OPTIMA study that one does not change the clinical diagnosis,” Prof. Bingisser explained.

Causes and presentations in old age

Common causes of acute abdominal pain include appendicitis, biliary colic, ureteral colic, diverticulitis, peptic ulcer, gastroenteritis, and nonspecific abdominal pain. Abdominal aortic aneurysm (BAA), intestinal perforation, acute pancreatitis, intestinal obstruction, and mesenteric ischemia are life-threatening. “Age is definitely a risk factor to consider in this regard: Patients over 50 years of age appear to be at increased risk for biliary pathology, nonspecific pain, appendicitis and obstruction. Older patients also present later and require a broader differential diagnosis. 20-33% require emergency intervention, and mortality rates are 15-34%,” Prof. Bingisser explained. “What we actually often miss are the malignancies, yet a full 10% of patients with nonspecific abdominal pain over the age of 50 suffer from such. Unfortunately, it eventually turned out that the patient from the casuistry was also one of them. Accordingly, special caution is required here.”

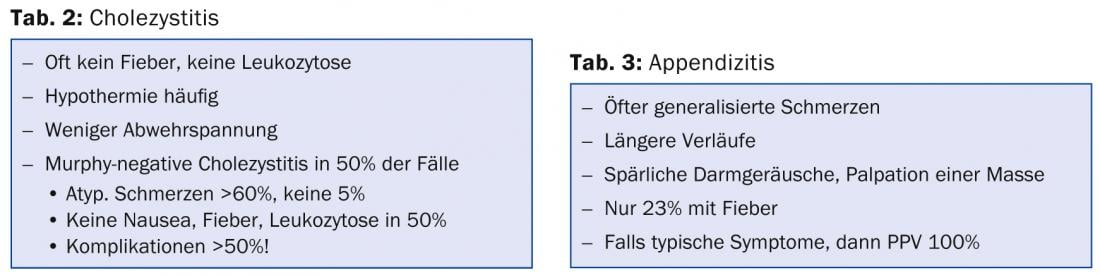

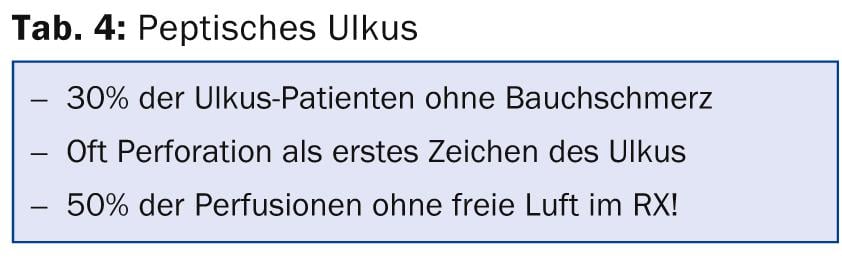

Practical tips and potential pitfalls in the management of cholecystitis, appendicitis, and peptic ulcer summarize Tables 2-4 .

Source: “Acute Abdominal Pain”, Seminar at SGIM Great Update, November 14-15, 2013, Interlaken.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(2): 38-40