Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is the most common liver disease worldwide. The German S2k guideline, updated in 2022, recommends screening patients at risk. The proposed screening algorithm includes fibrosis assessment and detection of steatosis as main elements and is largely consistent with EASL recommendations. The main pillars of therapy are lifestyle modification and control of comorbidities.

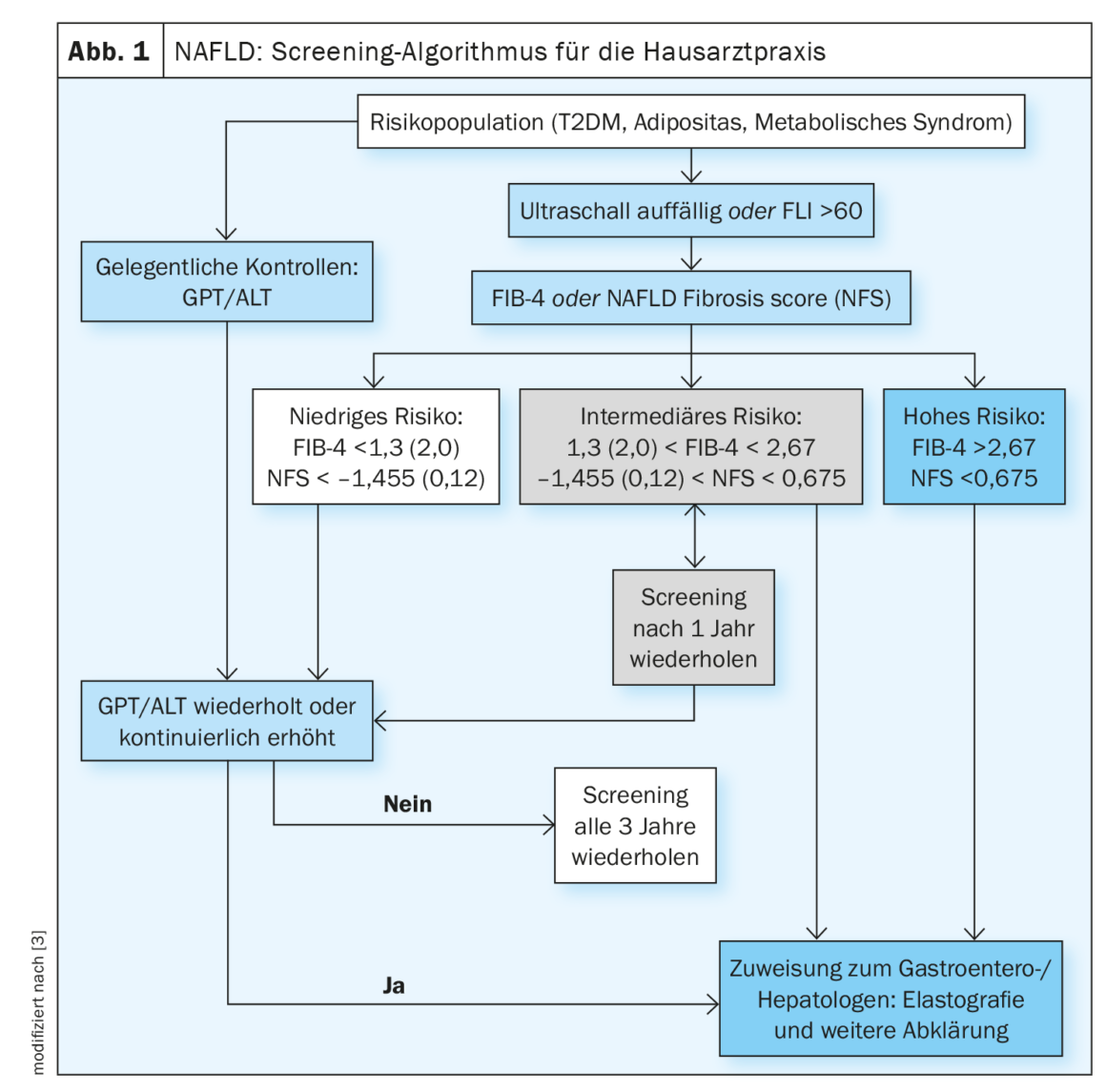

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a leading cause of liver-associated complications and death. An elevated fibrosis score is associated with an increased risk of complications. Regression from cirrhotic remodeling is possible [1]. In a study published in 2022, improvement in liver fibrosis was shown to reduce the risk of complications by 10-fold (HR, 0.08; 95% CI: 0.02-0.32) [2]. The screening algorithm for NAFLD proposed for the primary care setting (Fig. 1) includes scores such as AST/ALT quotient or FIB-4 [3]. Patients should be screened if they have one or more risk factors for advanced fibrosis: Age >45-55 years, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), metabolic syndrome, obesity (BMI >30 kg/m²), arterial hypertension [2,3]. T2DM and obesity are independent risk factors for the development of NASH-related fibrosis [4]. In patients with suspected NAFLD, transabdominal ultrasound acts as the primary imaging modality in screening.

Depending on the fibrosis stage, NAFLD patients have increased liver-related mortality and all-cause mortality compared with healthy controls [5,6]. Cardiovascular causes of death rank first among these [7,8].

In a retrospective analysis of 619 NAFLD patients over the period 1975-2005 and a median follow-up of 12.6 years, cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death (38%), followed by non-hepatic tumor disease (19%) and complications of liver cirrhosis (8%) [9]. Similar data come from two prospective studies from Sweden with follow-up up to 33 years: cardiovascular causes of death 43% and 48%, non-hepatic tumors 23% and 22%, and liver-related mortality 9% and 10%, respectively [10,11].

Screening of fibrosis progression in high-risk patients.

The s2k guideline suggests screening at-risk patients every 2-3 years using an algorithm that is largely consistent with that of the European Association for Study of the Liver (EASL) Clinical Practice Guidelines and other consensus recommendations for primary care physicians and diabetologists, but is simpler to use (Fig. 1) [3,12]. The FLI (fatty liver index) can be used for non-invasive determination of the fat content of the liver. Commonly used tools for noninvasive fibrosis prediction are the FIB-4 and the NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS).

The FIB-4 is easily calculated from the values of AST, ALT, platelets and the age of the patient. The evaluation is based on two cutoff values: patients with a value <1,45 haben ein geringes Fibroserisiko, während Patienten mit einem Wert>2.67 are at high risk for advanced fibrosis [13].

The NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) is easily calculated from standard laboratory values via an online input screen. The following parameters are entered for the calculation: Age, BMI, diabetes yes/no, AST, ALT, platelets and albumin. A value below -1.455 excludes advanced fibrosis with 90% sensitivity. An NFS >0.676 diagnoses advanced fibrosis with 97% specificity and 67% sensitivity.

Because both scores are largely based on routine parameters, they are well suited for use in a screening setting. Other noninvasive fibrosis scores, such as the AST/platelet ratio ( APRI) or the BARD (BMI, AST/ALT ratio, and diabetes) score, show good negative predictive values and are therefore useful for excluding advanced fibrosis.

The sequence of FLI (Fatty Liver Index) and FIB-4 has been decisively studied for screening in a high-risk population of type 2 diabetics [14].

The use of age-adjusted cutoffs may be appropriate to reduce the high proportion of intermediate-testing individuals. The management of intermediate-risk patients is a matter of debate and may vary (re-screening or direct referral to a hepatologist). Future studies need to show whether new surrogate markers (e.g., NIS4, FAST score) or imaging techniques such as MR elastography or MR-PDFF can also be used to assess individual fibrosis progression and progression in NASH [15].

NAFLD registry data provide insightful findings

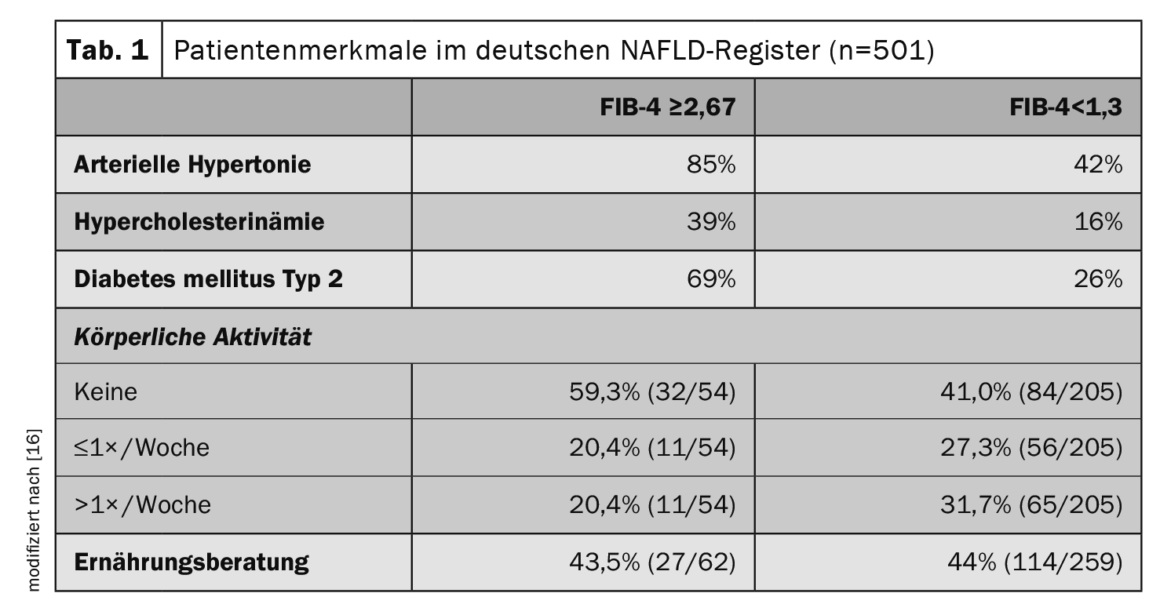

To find out more about the risk markers and prognostically significant factors associated with NAFLD, registry data are informative. The German NAFLD Registry is a prospective non-interventional study of the German Liver Foundation to describe clinical characteristics and disease courses of NAFLD patients in secondary and tertiary care settings [16]. Of 501 patients with NAFLD (mean age 54 years, 48% women), 13% had a high risk of advanced fibrosis (FIB-4 index ≥2.67) and 10% had a clinical diagnosis of cirrhosis. Statins were used in 22% of the total study population, whereas in diabetic patients, metformin, GLP-1 agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors were used in 65%, 17%, and 17%, respectively. Among patients with advanced fibrosis (FIB-4 ≥2.67), 85% had arterial hypertension, 69% had type 2 diabetes, and 39% had hypercholesterolemia (Table 1). Control of metabolic comorbidities and lifestyle changes (weight loss and exercise) are the mainstay of NAFLD therapy.

Congress: Praxis Update

Literature:

- «Leber», Gastroenterologie, Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Stallmach, Praxis Update, Berlin, 28-29.04.2023.

- Sanyal AJ, et al.: Cirrhosis regression is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2022; 75: 1235–1246.

- Roeb E, et al.: Collaborators: Aktualisierte S2k-Leitlinie nicht-alkoholische Fettlebererkrankung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS) – April 2022 – AWMF-Registernummer: 021–025. Z Gastroenterol 2022; 60(9): 1346–1421.

- Jarvis H, et al.: Metabolic risk factors and incident advanced liver disease in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based observational studies. PLoS Med 2020; 17: e1003100

- Dulai PS, et al.: Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017; 65: 1557–1565.

- Vilar-Gomez E, et al.: Fibrosis Severity as a Determinant of Cause-Specific Mortality in Patients With Advanced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Multi-National Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 443–457.

- Younossi ZM, et al.: Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016; 64: 73–84.

- Kim D, et al.: Association between noninvasive fibrosis markers and mortality among adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States. Hepatology 2013; 57: 1357–1365.

- Angulo P, et al: Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 389-397.e310

- Nasr P, et al.: Natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective follow-up study with serial biopsies. Hepatol Commun 2018; 2: 199–210.

- Ekstedt M, et al.: Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology 2015; 61: 1547–1554.

- Berzigotti A, et al.: EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines (Cpgs) On Non-Invasive Tests For Evaluation Of Liver Disease Severity And Prognosis- 2020 Update. J Hepatol 2021; DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.025.

- Kaswala DH, Lai M, Afdhal NH: Fibrosis Assessment in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in 2016. Dig Dis Sci 2016; 61: 1356–1364.

- Ciardullo S, et al.: Screening for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes using non-invasive scores and association with diabetic complications. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020; 8.

DOI: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000904. - Loomba R, et al.: Multicenter Validation of Association Between Decline in MRI-PDFF and Histologic Response in NASH. Hepatology 2020;

DOI: 10.1002/hep.31121. - Geier A, et al.: Clinical characteristics of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Germany – First data from the German NAFLDRegistry. Zeitschrift für Gastroenterologie 2023; 61: 60–70.

| Cover picture: Micrograph of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Masson’s trichrome & Verhoeff stain. Author: Nephron, wikimedia |

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(7): 28–29