Acne inversa is often confused with furunculosis, which means that it often takes years before a correct diagnosis is made. Smoking and obesity are strongly associated factors. Local disinfection of the skin lesions should be performed as a complementary therapy regardless of the severity of the disease. In case of non-response to therapy, it is recommended to quickly change the therapeutic approach. The affected patients often suffer from a significantly reduced quality of life and secondary psychological disorders.

The exact etiology of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa has not been fully elucidated to date, which is also expressed in the parallel diagnostic names used. Neither the original naming, describing the association with the apocrine sweat glands, nor the more recent term acne inversa, which classifies it as a member of the follicular occlusive triad, are pathogenetically correct. For this reason, the international study group for hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa has decided to use both names in parallel. In this article, which aims to convey the central contents of the guideline of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies [1], the term acne inversa is used for practical reasons.

Acne inversa is a chronic inflammatory disease of terminal follicles in the intertriginous areas. Affected patients often suffer from impaired quality of life and secondary mental disorders [2]. It often takes several years before a diagnosis is made.

The prevalence of the disease is approximately 1%, and women and men appear to be affected with equal frequency. The age at first manifestation is usually less than 30 years.

Pathogenesis

The inflammatory changes primarily affect the terminal hair follicle. Hyperkeratosis is thought to cause follicular occlusion. Follicular rupture and secondary infection induce an inflammatory reaction and subsequently a strong connective tissue reaction. In the course, nodules, fistulous ducts, sinus formations and scarring in the dermis develop.

Several trigger factors are known to influence this event. These include smoking, obesity, bacterial colonization, genetic predisposition, regional hyperhidrosis, and mechanical irritation.

Of particular note is the strong association between acne inversa and active smoking. A recent multivariate analysis showed that 90% of patients are smokers, making acne inversa a nicotine-dependent dermatosis [3]. Nicotine promotes follicular hyperkeratosis on the one hand, and acute inflammation on the other.

Unlike acne vulgaris, sebum production does not seem to influence the disease.

Clinic

Acne inversa manifests with fistulous comedones (Fig. 1) and painful, solitary, deep-seated nodules (Fig. 2).

In the course, abscesses and fistula tracts develop (Fig. 3), which are accompanied by considerable fibrosis. The occurrence of scar contractures may result in restricted movement.

The disease is limited to the intertriginous areas. The preferred sites are inguinal (90%), axillary (69%), perianal and perineal (37%), gluteal (27%), submammary (18%), and genitofemoral and the mons pubis. In most cases, more than one region is affected and a symmetrical affection is seen. Pilonidal sinus is present in 23-30% of acne inversa patients.

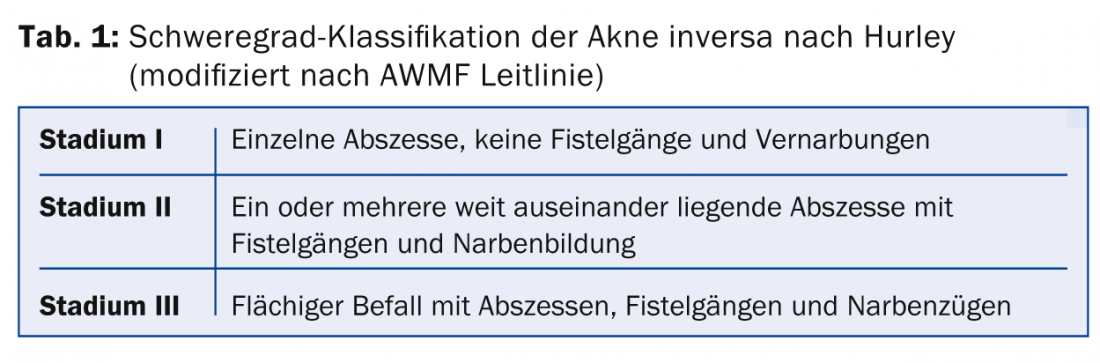

Severity classification

For documentation purposes, the classification according to Hurley (stages I-III), which includes a clinical assignment (Tab. 1) , has proven to be useful. This classification facilitates the development of therapy goals and the monitoring of therapy success.

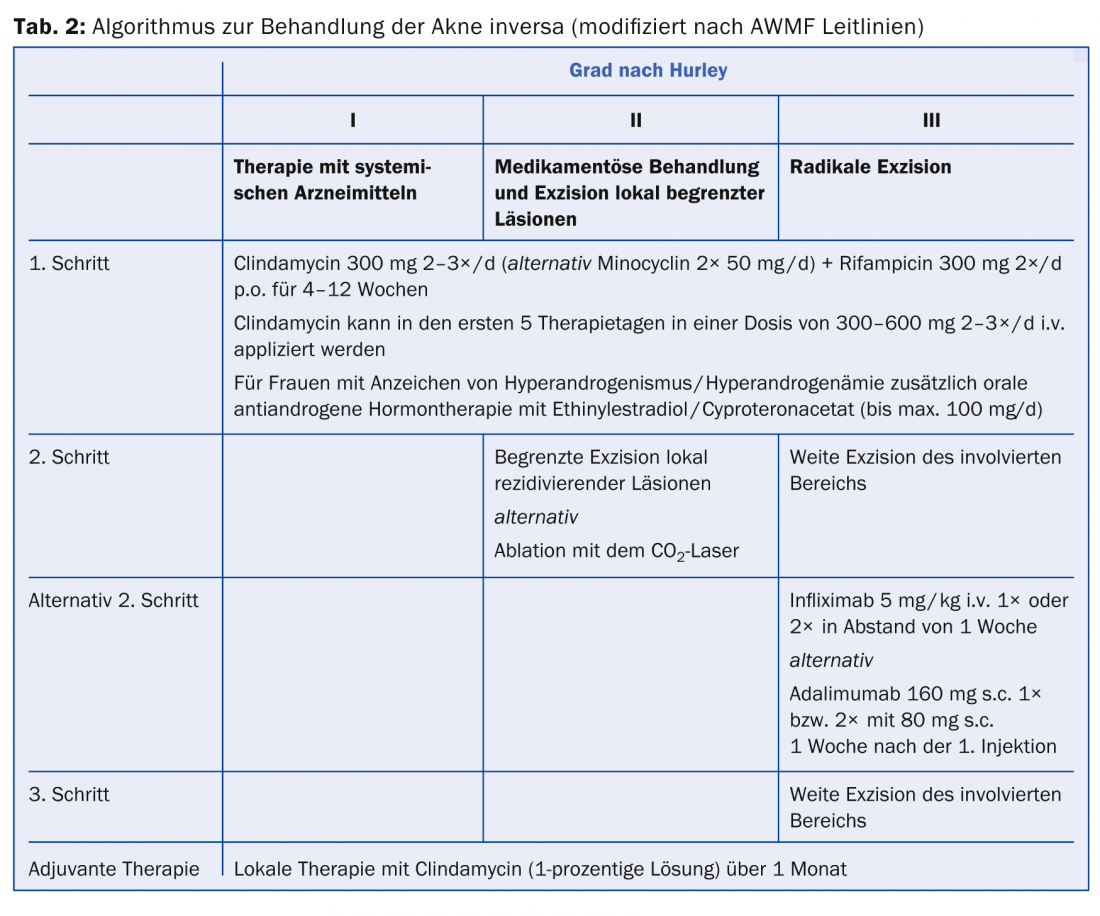

Therapy

There is no universal scheme for the therapy of acne inversa. It is important to change therapy regimens early in the absence of response to prevent disease progression. When selecting a suitable therapy, the clinical manifestation (corresponding to the Hurley stage) must also be taken into account (tab. 2) . In addition to the forms of therapy described below, accompanying measures such as nicotine cessation, weight reduction, refraining from shaving and avoiding tight-fitting clothing are important therapy goals [4]. Since secondary psychological problems often occur in acne inversa, depending on the severity of the disease, particular reference should also be made to psychological care.

The care of acne-inversa patients is a great challenge and requires interdisciplinary care by dermatologists, psychiatrists, surgeons and gynecologists due to the comorbidities and therapeutic approaches.

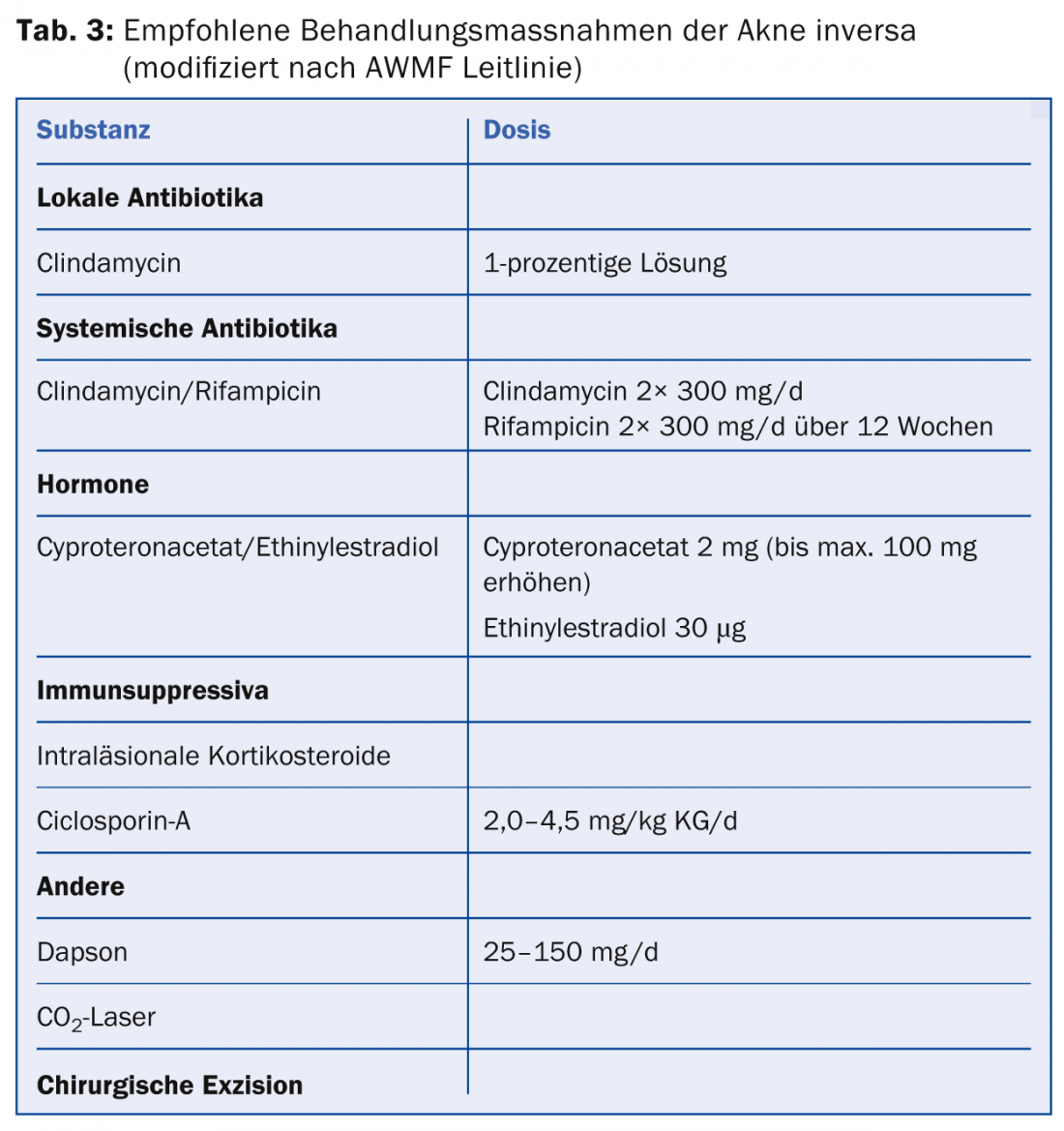

Table 3 provides an overview of the various therapeutic approaches, which are now described in more detail.

Surgical therapy

For lack of other suitable and curative forms of treatment, the most effective therapy continues to be complete excision of the diseased areas. The topic of surgical therapy in the context of acne inversa is explained in more detail in the article by Dr. med. Gerald Gubler (Senior Physician Surgery Stadtspital Triemli) and PD Dr. med. Dindo (Head of Proctology Stadtspital Triemli Zurich).

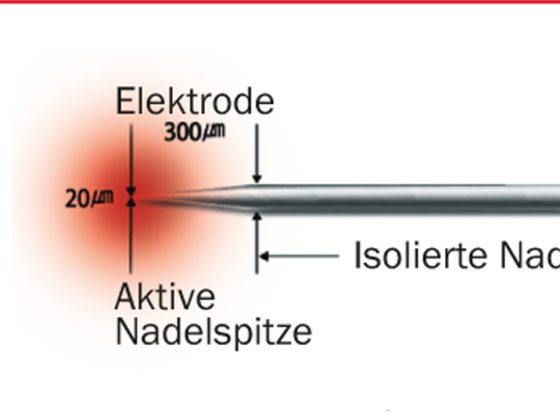

Laser therapy

In a study published in 2002, ablative laser therapy showed good results in the treatment of acne inversa with a recurrence rate of 12.5% and cosmetically and functionally good results [5]. However, no controlled comparative studies exist to date.

In contrast to ablative laser therapy, which acts as an alternative to surgical radical rehabilitation, conservative laser therapy aims to destroy hair follicles. In a controlled prospective study using long-pulsed neodymium YAG laser, there was a 65% improvement in symptoms, although symptom reduction varied by location [6]. Inguinal achieved the best results (73.4% improvement).

Diode laser (1450 nm) and dye laser treatments have also been shown to improve acne inversa in case reports.

However, further comparable studies are needed to determine laser-assisted depilation as a generally recommended method.

Topical therapy

Local therapy with clindamycin (1-percent solution) is recommended both in the initial stage and as adjunctive therapy to systemic or surgical therapy.

Furthermore, resorcinol peeling and intralesional corticosteroid therapy may be considered for mild clinical manifestations.

Systemic therapy

First-line systemic therapy is equivalent to combination therapy of clindamycin 300 mg 2×/d and rifampicin 300 mg 2×/d for one to three months. This therapy decreases colonization of hair follicles with bacteria and various proinflammatory mechanisms. The main side effect of this therapy is clindamycin-induced diarrhea. If intolerant, clindamycin can be replaced with minocycline (50 mg 2×/d). Contraindications include severe liver dysfunction and, in the case of rifampicin and minocycline, pregnancy.

Hormonal antiandrogens

If there is no response to systemic antibiotic therapy, antiandrogenic therapy with ethinyl estradiol 30 µg/cyproterone acetate 2 mg is recommended. However, this should never be used as primary monotherapy. The recommended duration of therapy is at least six months. Hormonal antiandrogenic therapy may also be considered, particularly in patients with moderate acne inversa and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). The mechanism of action is via a reduction in free testosterone.

When initiating therapy, particular attention should be paid to the increased risk of thrombosis, possible drug interactions, and clarification of any risk factors in the context of cardiovascular morbidity. In this context, nicotine use is an absolute contraindication in women over 35 years of age.

Retinoids

Oral systemic therapy with retinoids is not recommended for acne inversa.

As an exception, positive results have been described in refractory acne inversa after acitretin therapy [7]. In skin, acitretin affects mitotic activity and differentiation of keratinocytes, slows intraepidermal migration of neutrophil granulocytes, and inhibits IL-6-induced induction of Th17 cells. Important contraindications are pregnancy due to embryotoxicity and severe renal or hepatic dysfunction.

Dapsone

Dapsone appears to produce good results at doses of 25-150 mg/d [8]. Before starting therapy, the enzyme activity of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase must be measured. Adverse drug reactions include hemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, blood count changes, and hepatitis. Regular blood count checks and determination of methemoglobin levels must be performed during therapy.

Immunosuppressants

Due to their anti-inflammatory effect, immunosuppressants show a moderate to good effect in acne inversa, but acute recurrences are observed after discontinuation of therapy. These effects could only be observed for ciclosporin A. Methotrexate and azathioprine are not recommended due to insufficient experience. Because of the side effect profile, the risk-benefit ratio must always be considered.

Biologics

Biologics have been successfully used in patients with severe acne inversa (Hurley III) as short-term therapy with respect to preparation for curative surgical intervention. Limiting factors for a therapy with biologics are the lack of curative effect, the high costs and the possible side effects in long-term therapy. The positive effect was seen with the tumor necrosis factor blockers adalimumab and infliximab, whereas etanercept was not very effective.

Possible contraindications such as heart failure NYHA III-IV, pre-existing severe infections (including tuberculosis), as well as pregnancy and lactation must be taken into account during therapy with biologics.

Other therapeutics

The use of botulinum toxin-A, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and cryotherapy must be discouraged due to lack of experience.

Radiotherapy achieved symptom relief in 38% of patients and improvement in 40% in one study [9], but radiotherapy is not recommended because of the risk of secondary tumors in the predominantly young patients. In addition, the presence of radiodermatitis may complicate subsequent surgery.

Literature:

- Zouboulis CC, et al: S1 guidelines for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. www.awmf.org.

- Meixner D, et al: Acne inversa. JDDG 2008; 6: 189-196.

- Revuz JE, et al: Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two case-control studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 5: 596-601.

- Mühlstädt M, et al: Acne inversa (Hidradenitis suppurativa). From diagnosis to therapy. Dermatologist 2013; 64: 55-62.

- Lapins J, et al: Scanner-assisted carbon dioxide laser surgery: a retrospective follow-up study of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47: 280-285.

- Thierney E, et al: Randomized control trial for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser. Dermatol Surg 2009; 35: 1188-1198.

- Boer J, et al.: Long-term results of acitretin therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa. Is acne inversa also a misnomer? Br J Dermatol 2011; 164: 170-175.

- Kaur MR, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa treated with dapsone: A case series of five patients. J Dermatolog Treat 2006; 17: 211-213.

- Frohlich D, et al: Radiotherapy of hidradenitis suppurativa – still valid today? Strahlenther Onkol 2000; 176: 286-289.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2015; 25(1): 6-10