“Personalized medicine” is almost a buzzword these days. But it doesn’t just affect the genetic side of medicine. Today, it is also impossible to imagine everyday practice without taking (inter)subjective concepts of illness and patient-centered communication into account.

Consideration of individual personality traits is also important in the clinical context and can contribute decisively to successful conversation and patient management [1]. “Personality traits determine under which life circumstances a person becomes sensitive to certain illnesses, how he or she reacts to such, how the relationship with the doctor is formed (i.e. how the conversation with him or her also proceeds), how he or she implements the suggestions, recovers from the illness or not,” said conference chairman Prof. Roland von Känel, M.D., chief physician for psychosomatic medicine, psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Barmelweid Clinic.

Prof. Dr. med. Rainer Schäfert, structural professor and head physician for psychosomatics at the University and University Hospital Basel, went into more detail on one of these aspects, namely the doctor-patient relationship. While disease/organ-centered medicine primarily illuminates the biological dimension of a disease in a differentiated manner and targets objective findings, patient-centered medicine attempts to build a bridge to the subjective condition and thus perceive the person not only on a biological level, but also on a psychological and social level, i.e. as a whole. Patient-centered care can be conceptually understood in five dimensions [2]:

- Under the bio-psycho-social perspective form

- the patient as subject,

- but also the doctor as subject together a

- therapeutic alliance with

- shared power and responsibility.

Doctor-patient relationship

While the earlier paternalistic doctor-patient model still placed the majority of decisions to be made with the doctor and expected compliance from the patient, the participatory model with shared decision making and an optimally adherent patient – in recent times even partly replaced by a consumer-oriented information model – has been increasingly gaining ground since the 1990s, where the physician exclusively assumes the role of an expert, provides the patient (or “customer”) with information, advises him and largely leaves (even difficult) decisions to him (which can lead to excessive demands on the part of the patient).

The shift toward participation requires a patient who is willing and able to participate actively and communicatively in the new style of treatment. At least the will seems to be there: According to major surveys, a good half of patients in Germany prefer the participatory style. And Scandinavian respondents [3] also recommend primary care physicians especially if they involve them in their decisions about medical treatments, listen to them, take an interest in their personal situation, make it easy for them to talk about problems, and help them deal with feelings related to health. But not only that: comprehensive information, thorough physical examination and competent approach, clear goal setting, and good preparation in the context of referrals are also important.

Consequently, both competencies, a more biomedically motivated one and a patient-centered one, are desirable and complementary.

How do I communicate with my patient?

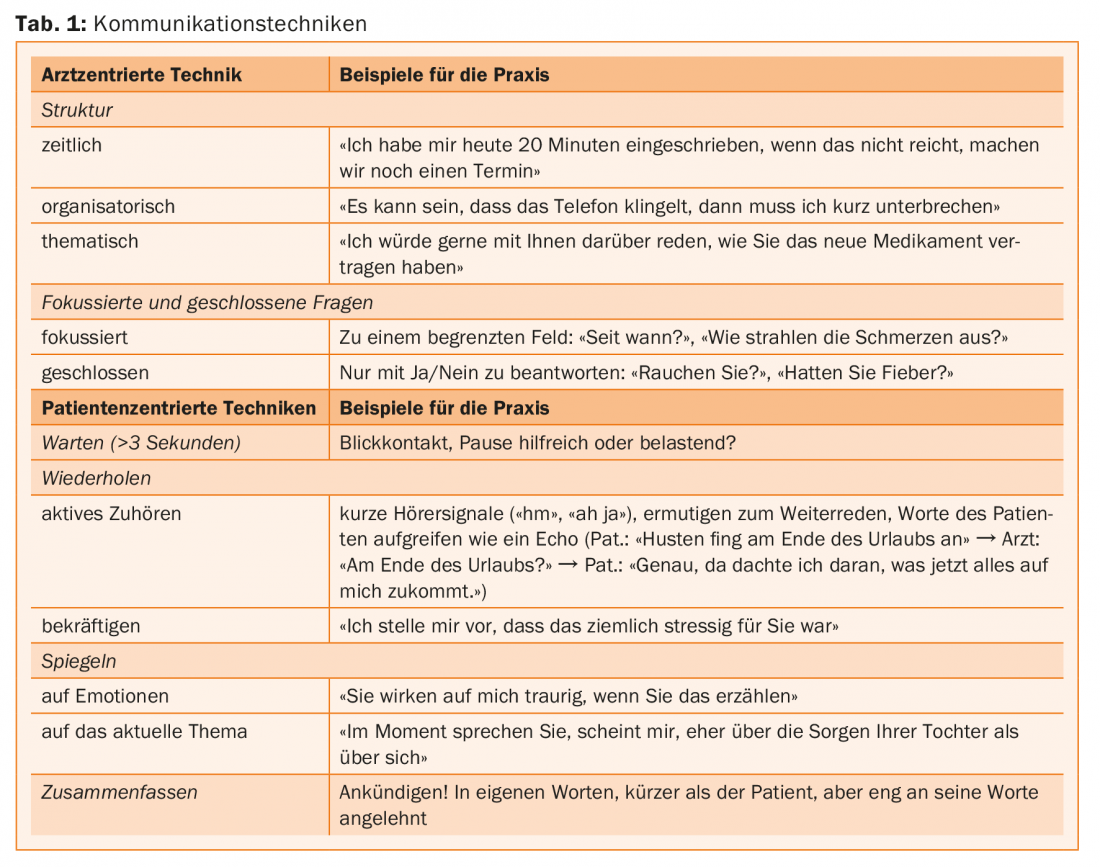

Communication as a field of activity and mirror of the doctor-patient relationship should contain both aspects, the doctor-centered and patient-centered perspective [4,5]. “It is important to be able to use the approaches in a complementary and competent way when talking to the patient,” he said. The physician-centered technique includes clear indications of the temporal, organizational, and thematic structure of the interview, as well as focused and closed questions. Narration tends to be inhibited; it is a matter of testing hypotheses. Patient-centered technique includes deliberate pauses, eye contact, repetition, mirroring emotions, and summarizing. Narration is encouraged, hypotheses are generated together (Tab. 1). “When switching from one modality to the other, the reins are metaphorically handed over to the interlocutor, which of course involves a certain danger, since you don’t know where the new carriage driver will take you,” Prof. Schäfert explained.

You move from doctor-centered communication to patient-centered communication by purposefully establishing eye contact and building in pauses, asking open-ended questions, and actively listening. “By the way, one open question is usually enough (so it is not: the more, the better). This is already a strong invitation to the patient, which is usually used,” the expert elaborated.

Returning to the physician-centered perspective is accomplished by summarizing what has been said, announcing the change and obtaining consent, and transitioning into more focused and closed questions. This may also be necessary if the patient is not at all familiar with the area, takes too large detours, or “runs away with the horses” (to stay with the coachman metaphor), i.e. very strong emotions, pronounced hopelessness, or dissociation occur.

Is patient-centered communication effective, then?

“In this context, I’m afraid I have to give you a bit of a damper: For if the patient-centered approach is intuitively useful and enriching, the evidence base is complex: communication training, even shorter programs, has been successful in training conversational techniques [6], but mixed results have been found to date for patient satisfaction or health outcomes [6]. A training of residents and nursing trainees in communication about end-of-life care even led to an increase in depressiveness at the patient level-possibly because the candidates’ therapeutic competence was insufficient to absorb the emotions that arose [7]. After all, the limited poolable data from the Cochrane review on patient-centered communication show small positive effects on health status [6], and its use in patients with IBS also resulted in significant improvement in symptom severity and quality of life [8].

Pitfalls of personalized medicine

“Genetics as a hobbyhorse of personalized medicine is developing immensely and is also taking on an ever greater role in everyday practice – an impressive example being oncology,” said Prof. Andreas Papassotiropoulos, MD, of the Department of Molecular Neuroscience at the University of Basel, introducing his talk. “We’re seeing a revolution in genetic and biological findings, which of course can be correlated to clinical findings – just as everything in medical research is actually correlative. However, you have to be careful what you correlate and what conclusions you draw from it.” On the one hand, the phenotype that you want to correlate with certain genes is crucial. The search for a gene for the extremely complex construct “religiosity” (in the sense of a personality trait), for example, appears to be a nonsensical application. Second, and this is a common misconception, the separation of group statistics from the individual is central. “Unfortunately, this difference is very difficult to communicate,” the speaker said. But imagine, for example, using age and gender, which were found to be statistically significant risk factors for Alzheimer’s dementia in a large enough group, to predict an individual’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Of course, these risk factors are highly significant, but that does not mean that they can really discriminate well in the clinic. To do this, we need a method like ROC analysis, which distinguishes a good test with an area under the curve (AUC) 90% from a poor one with an AUC 65%. To stay with the above example, even if one adds the gene component, i.e. APOE, as a further statistically significant risk factor in AD – or even all known genetic loci associated with AD, the clinical discrimination in the single individual, i.e. the individual risk prediction thus remains deficient [9].

“Predictions based on such studies, as commercially undertaken by 23andMe, are not only amusing (e.g., 23andMe predicts one’s earwax type), but carry a real danger, such as when they pretend to be able to predict an individual’s risk of suicide or depression – and promote it in the sense of a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy.’ In fact, we experienced the misapplication of such study results firsthand, so to speak, namely when I noticed that our study on the KIBRA protein [10], which is associated with memory performance, was being used by 23andMe to predict individual memory performance in the paying customer – which is, of course, highly unscientific and therefore problematic.”

Source: 3rd Swiss Symposium on Psychosomatics, September 1, 2017, Zurich

Literature:

- Adler R, Hemmeler W: Anamnesis and physical examination. 3rd ed. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart 1992.

- Mead N, Bower P: Soc Sci Med 2000 Oct; 51(7): 1087-1110.

- Vedsted P, Heje HN: Scand J Prim Health Care 2008; 26(4): 228-234.

- Langewitz W: Patient-centered communication. In: Adler RH, et al. (Ed.): Uexküll. Psychosomatic Medicine. Theoretical models and clinical practice. Munich, Elsevier, Urban & Fischer, Munich 2011; 338-347.

- Schaefert R, Hausteiner-Wiehle C: Taking a medical history. In: Rief W, Henningsen P (eds). Psychosomatic and behavioral medicine. An introduction to psychosomatic medicine and health psychology. Schattauer, Stuttgart 2015; 296-312.

- Dwamena F, et al: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Dec 12; 12: CD003267.

- Curtis JR, et al: JAMA 2013; 310(21): 2271-2281.

- Kaptchuk TJ, et al: BMJ 2008; 336(7651): 999-1003.

- Seshadri S, et al: JAMA 2010; 303(18): 1832-1840.

- Papassotiropoulos A, et al: Science 2006; 314(5798): 475-478.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(5): 37-39.