In the course of the 6th Annual Meeting of the German Society of Nephrology (DGfN) in Berlin, a press conference was held to discuss the extent to which modern dialysis influences long-term survival, how confidence in transplantation medicine could be strengthened, and what options exist for kidney regeneration.

According to Prof. Jan Galle, MD, Lüdenscheid, Germany, the 5-year survival of patients new to dialysis is 39.3% for those over 65 and 21.3% for those over 75 – these are still low figures. At the same time, there are so-called long-term dialysis patients, some of whom survive on dialysis for up to 40 years. Thus, there must be a significant difference between the average and long-term dialysis patients. “And there is: namely the concomitant diseases. Over 33% of neudialysis patients have diabetes and must receive dialysis due to diabetic nephropathy. The average patient is older and has numerous comorbidities – such as hypertension, diabetes, or obesity (metabolic syndrome). He may smoke, and it is not uncommon for him to have had heart attacks and strokes. All this, of course, significantly impairs the prognosis. To put it provocatively: it is not the need for dialysis that kills, but the concomitant diseases,” he said.

Young patients without damage to the vessels can benefit greatly from sophisticated dialysis technology and careful nephrological care; they not infrequently become long-term patients who survive years and decades on dialysis.

Postmortem vs. living donation

It is clear that the number of patients waiting for a kidney is disproportionately higher than the number of actual kidney transplants. Prof. Dr. med. Jürgen Floege, Aachen, spoke on this topic. The negative trend continues unabated (also due to the sharp decline in the number of donors), which means that waiting times are becoming longer and longer: On average, a patient currently has to wait about five to six years for a kidney.

Survival with a transplant is significantly better after living donation than after postmortem donation. “There is a comprehensive and clear body of data on this,” Prof. Floege affirmed. Based on individual case reports, living donation is also increasingly being critically examined – but are these expressed doubts well-founded and scientifically substantiated?

The assessment of donor risk depends to a crucial extent on the comparison group:

If this is the age-matched normal population, living kidney donors show longer survival and a lower risk of developing dialysis.

However, if these are control subjects who are considered to be in above-average health in most respects, living kidney donors have a slightly increased risk of needing dialysis themselves one day (in absolute numbers). So the risk is not zero, but the success rates are basically very good.

“Of course, there are also contraindications in the guidelines that prohibit kidney donation. Donors must have two normally functioning kidneys and must not suffer from any diseases relevant to donation (which, by the way, does not yet include moderate well-controlled hypertension),” the expert explained. In an initiative, the DGfN and the Bundesverband Niere e.V. call for a transplant registry (already in preparation) as well as a secure deposit of donor willingness (available at the intensive care unit). There are also calls for the creation of lay understandable educational questionnaires for patients (recipients and donors) as well as better information for the general population in general.

Regenerate diseased kidneys

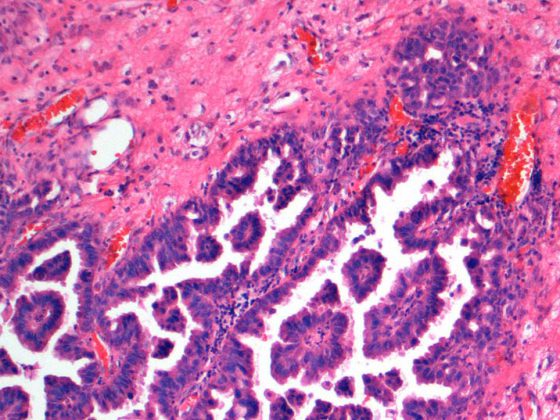

A research overview on the regeneration of diseased kidneys was provided by Prof. Christian Hugo, MD, Dresden. Of course, dialysis already represented a major advance in the field of kidney replacement procedures, but further development will go in a different direction: The goal is regeneration. At best, healthy kidney tissue should “grow back”, this is the approach currently still considered more of a vision by researchers worldwide. In the animal world, the regeneration of nephrons after damage already takes place, e.g. in zebrafish by means of various progenitor cells (as shown in 2011 [1]). To generate a large number of nephrons, transplantation of 10-30 such cells is sufficient. Similar progenitor cells also exist in mammals, so one would need to identify and engineer them (cell engineering) to develop regenerative kidney therapies. Among other things, the concept discovered by Shin`Ya Yamanaka that basically every mature cell (e.g. a skin cell) can be converted into a stem cell could help here.

A research project [2] has recently been able to direct the differentiation of embryonic stem cells – which per se raises ethical concerns – towards the formation of kidney-specific progenitor cells complete with nephrons and a renal structure.

Also in 2014, researchers [3] developed kidney-specific stem cells from human skin cells in the Petri dish, which then form kidney tubule structures.

The complete decellularization of the kidney down to the matrix with subsequent reconstruction (re-cellularization with healthy cells and further cultivation in a so-called bioreactor) represents another promising approach already tested in animal experiments [4].

Lastly, there are efforts to slow down the progression of the disease (in the ongoing process) and steer it towards a cure. Structures and cells would then need to be adequately replaced by adult stem or progenitor cells to stimulate/control the regenerative process. At this year’s DGfN congress, various theories on this were discussed and new results were presented [5–7].

Source: Press conference for the 6th Annual Meeting of the German Society of Nephrology (DGfN), September 8, 2014, Berlin.

Literature:

- Diep CQ, et al: Identification of adult nephron progenitors capable of kidney regeneration in zebrafish. Nature 2011 Feb 3; 470(7332): 95-100.

- Takasato M, et al: Directing human embryonic stem cell differentiation towards a renal lineage generates a self-organizing kidney. Nat Cell Biol 2014 Jan; 16(1): 118-126.

- Lam AQ, et al: Rapid and efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intermediate mesoderm that forms tubules expressing kidney proximal tubular markers. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014 Jun; 25(6): 1211-1225.

- Song JJ, et al: Regeneration and experimental orthotopic transplantation of a bioengineered kidney. Nat Med 2013 May; 19(5): 646-651.

- Starke C, et al: Renin-derived cells are adult progenitor cells of the mesangium in mesangial cell injury. DGfN Congress 2014; Abstract FV11.

- Hickmann L, et al.: Evidence for the existence of a precursor pool for renin-producing cells. DGfN Congress 2014; Abstract FV12.

- Sradnick J, et al: Regeneration of endothelial cell damage in the mouse kidney occurs without recruitment of cells from an extrarenal stem cell niche. DGfN Congress 2014; Abstract P027.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(5): 26-27