Sports activities can lead to structural and electrical changes in the heart in a volume- and intensity-dependent manner. A comprehensive overview of the resulting peculiarities in high-performance athletes, including advice on possible sports and competition fitness.

There is no universal definition of competitive sports. From a sports cardiology perspective, this is understood to mean regular physical training of more than ten hours per week, combined with competitive activity in individual or team sports and frequent peak loads at the athletes’ personal limit [1].

Sports activities can lead to structural and electrical changes in the heart in a volume- and intensity-dependent manner. Especially for sports with a high dynamic component (e.g. jogging, cycling, cross-country skiing) a high cardiac output is required. Competitive exercise can lead to harmonic enlargement of all cardiac cavities and eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy [2].

Even though the “athlete’s heart” is a physiological adaptation to exercise, it can promote cardiac remodeling, bradycardia, and tachycardia. In this context, atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia, usually occurring after the top sports career (>35 years), which was documented for the first time in former Finnish orienteers [3]. In addition, increased sinus bradycardia (<40/min), AV block (PQ >250 ms), and implanted pacemakers were found in former Tour de Suisse professional cyclists compared with age-matched control subjects [4]. Controversy exists as to whether intense exercise can lead to a phenotype similar to arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) and consecutive ventricular arrhythmias via volume and pressure loading of the right ventricle. However, this probably requires a certain predisposition (genotype) [5].

Preventive examination and cardiological clarification

In Switzerland, according to European recommendations, an annual physical examination, personal and family history, and ECG are performed in cadre athletes [5]. The ECG must be evaluated according to specific criteria [6]. Even in asymptomatic athletes, arrhythmias or a possible risk for arrhythmias can be detected in this way. In addition, palpitations are among the most common symptoms for which athletes are referred for a cardiological examination. In addition to dizziness and decreased performance and, in rare cases, syncope, these complaints may indicate an underlying cardiac arrhythmia.

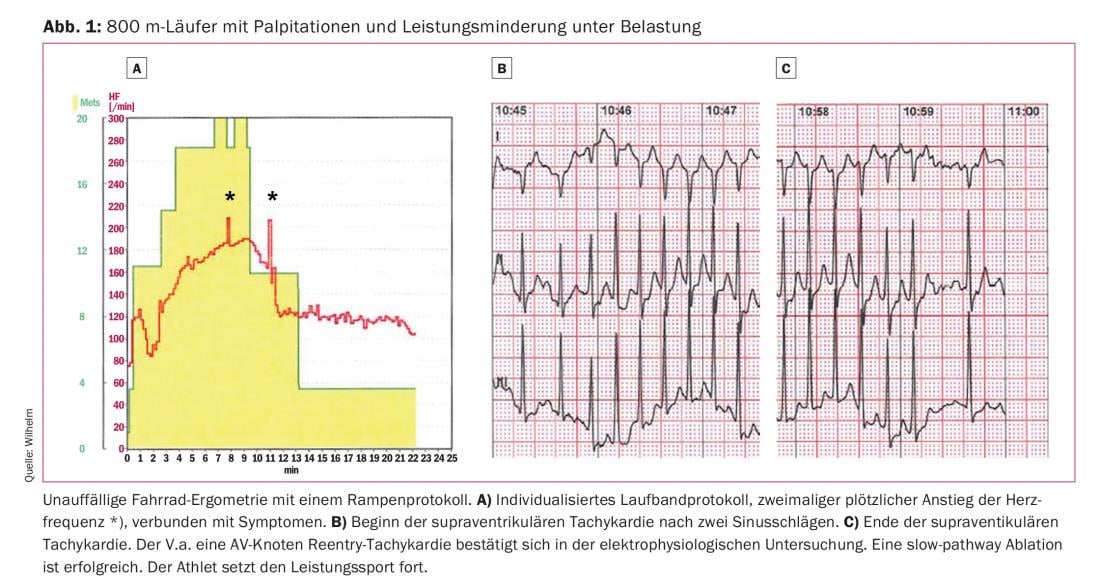

The important goal of the evaluation is to exclude structural, electrical or coronary heart disease, as well as to determine the fitness for sports and competition. Hyperthyroidism, anemia, or iron deficiency should be ruled out by laboratory chemistry. Diagnostics for symptom-rhythm correlation are required. This can be done in the performance test and/or by long-term monitoring of the heart rhythm. It should be noted that exercise-induced arrhythmias may not be triggered in a conventional performance test with a ramp or step protocol, but require a protocol adapted to the sport-specific exercise situation (Fig. 1). The exclusion of structural heart disease is initially performed with transthoracic echocardiography. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful for specific issues (myocarditis, ARVC). If pretest probability is appropriate, cardiac CT may be performed to rule out coronary artery disease. Very rarely, invasive diagnostics are required. An electrophysiologic study is usually performed in combination with ablation when cardiac arrhythmia is already documented [7].

Bradyarrhythmias

Sinus bradycardia (≥30/min), junctional replacement rhythm, AV block I° (PQ <400 ms), and AV block II° type Wenckebach at rest are normal findings in high-performance athletes. In addition to a high vagotone, this is also caused by remodeling of the stimulus formation and conduction system. They do not require further clarification in asymptomatic athletes [6].

If symptoms are present, a performance test should be performed to document physiologic adaptation of the heart rhythm. Sinuatrial (SA) block with pauses >3 seconds or sinus bradycardia <30/min should be further evaluated, especially in symptomatic athletes. AV block II° type Mobitz and AV block III° indicate infrahissary conduction disturbance and require further evaluation. A pacemaker indication is made according to the general guidelines [7]. Even with a pacemaker, competitive sports can often be continued. Limitations exist in the case of underlying structural heart disease. Attention must be paid to a potentially somewhat higher risk of electrode dysfunction in corresponding high-risk sports (contact sports). Athletes without intrinsic rhythm should be discouraged from competitive sports in these disciplines.

Supraventricular arrhythmias

Sinus arrhythmias and ectopic atrial rhythms are normal findings in high-performance athletes and usually do not require further evaluation [6]. Thyroid dysfunction should be excluded in cases of clustered supraventricular extrasystoles [7].

AV nodal reentry tachycardia, AV reentry tachycardia (WPW syndrome), and atrial tachycardia do not occur more frequently in athletes than in the normal population. However, physical activity can be a trigger for a tachycardia episode, and the rapid heart rate with loss of AV synchronization can lead to dizziness and decreased performance. Drug therapy is often not indicated. After explanation of the benefits and risks, ablation is the treatment of choice [7].

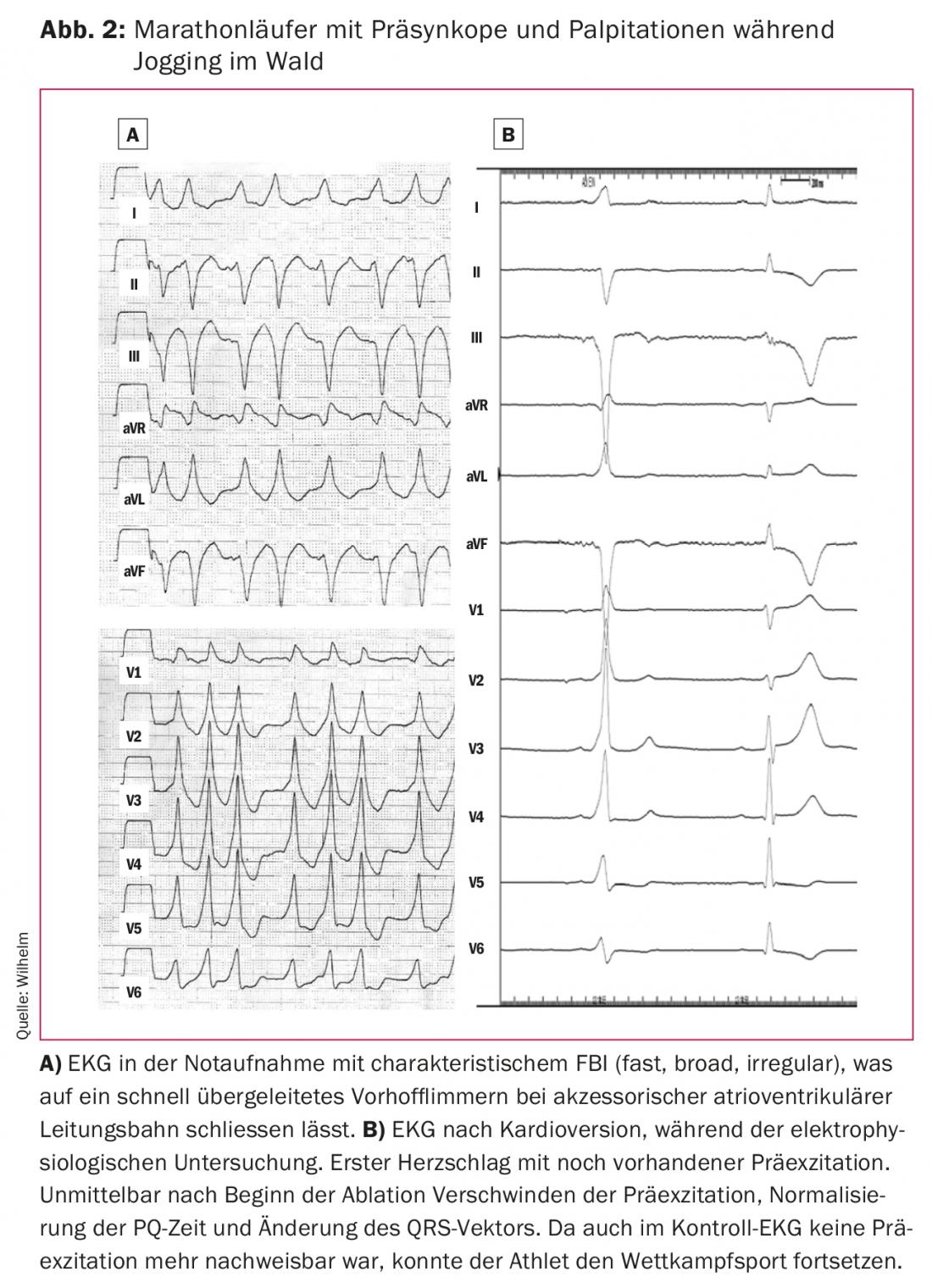

On resting ECG, asymptomatic preexcitation in accessory atrioventricular pathway should not be missed. Preexcitation and endurance exercise favor atrial fibrillation. The high atrial frequencies can then lead to rapid ventricular rhythms via the accessory pathway, which is often not frequency modulating, and these rhythms can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation (Fig. 2) . In these cases, the accessory pathway should be ablated in any case. In the case of incidental findings, without documentation of tachycardia, ablation is performed after appropriate risk stratification (documentation of a rapidly conducting pathway in the electrophysiological study or exercise test, generous indication in competitive sports) [7].

Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter occur more frequently in high-performance athletes than in the normal population. There is an association with training volume and intensity [8]. Even if a reduction in training volume would be the therapy of choice, this is not preferred by many athletes. Drug and interventional therapy, as well as anticoagulation strategy, follows general guidelines. Because drugs like Cordarone® cause photosensitization, they are not well tolerated in outdoor sports. Therefore, in atrial fibrillation, pulmonary vein isolation may be the first-line therapy. Isthmus ablation should be preferred to drug therapy for typical atrial flutter [7].

Competitive sports can usually be continued after successful treatment (ablation, rate control in atrial fibrillation) and exclusion of structural heart disease in all supraventricular arrhythmias.

Ventricular arrhythmias

Ventricular extrasystoles (VES) are a common incidental finding in athletes. If they occur infrequently (≤1 VES per side rhythm strip at 25mm/s), they do not require further workup [6]. They often disappear in the stress test. If there are two or more VES per side rhythm strip or if VES increases with exercise, a 24-hour ECG should be performed. In one study, athletes with more than 2000 VES in 24 hours or nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (≥3 VES) had underlying heart disease in 30% of cases [9]. Structural heart disease should be excluded in these athletes.

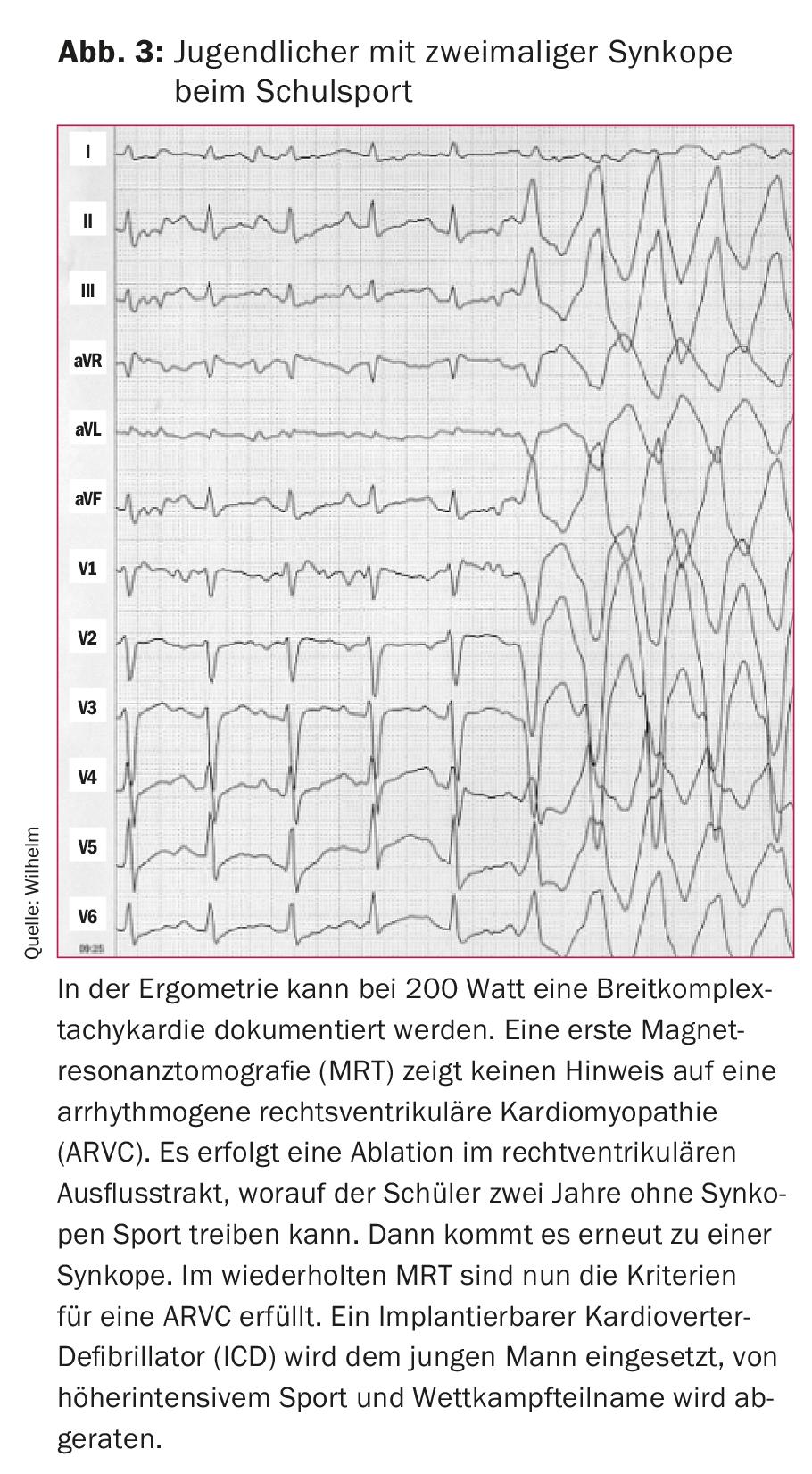

Persistent, monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) may be idiopathic or reflect structural heart disease (myocarditis, ARVC). In particular, rapid and symptomatic VTs originating from the right ventricular outflow tract should be ablated (Fig. 3).

Polymorphic VTs, ventricular flutter, and ventricular fibrillation often lead to syncope, cardiac arrest, and, in rare cases, sudden cardiac death. They may be the initial manifestation of electrical (long-QT syndrome, catecholaminergic polymorphic VT), structural (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [HCM], ARVC, myocarditis), or coronary artery disease in otherwise asymptomatic athletes. Data from the United States and Italy suggest that cardiomyopathies (HCM, ARCV) are the most common underlying heart diseases. In contrast, studies from Switzerland and other regions of the world show that coronary artery disease and unexplained cases are most common in sudden cardiac deaths of young competitive athletes [10].

Therapy (beta blocker and/or implantable cardioverter defibrillator [ICD]) and possibility to continue competitive sports should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team (electrophysiology, medical genetics, sports medicine) including the athlete. An ICD indication does not automatically mean a ban on competitive sports. Rather, it is important to consider the underlying condition that led to the ICD indication (e.g., strict prohibition of competition in ARVC). The 2005 European Guidelines [1] are much more restrictive in this regard than the more recent 2015 guidelines from the United States [7]. Especially in patients with long-QT syndrome or HCM who are well controlled with medication and free of symptoms and arrhythmias, it must be decided on a case-by-case basis whether competitive sports and competition can be continued.

Take-Home Messages

- High performance exercise leads to structural and electrical remodeling of the heart. There are special criteria for resting ECG evaluation.

- Apart from atrial fibrillation, cardiac arrhythmias do not occur more frequently in high-performance athletes than in the normal population. In sports-associated ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, there is usually underlying heart disease.

- Asymptomatic athletes require further evaluation only if ECG findings are atypical for elite sports. Symptomatic athletes and/or positive family history of myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death should always undergo cardiac evaluation.

- The therapy of cardiac arrhythmias is carried out according to the guidelines.

- Continuation of competitive sports is usually possible in the case of supraventricular arrhythmias, in the case of ventricular arrhythmias and/or presence of a pacemaker or ICD depending on the underlying heart disease or decision in the multidisciplinary team involving the athlete.

Literature:

- Pelliccia A, et al: Recommendations for competitive sports participation in athletes with cardiovascular disease: a consensus document from the Study Group of Sports Cardiology of the Working Group of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology and the Working Group of Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2005; 26(14): 1422-1445.

- Maron BJ, et al: The heart of trained athletes: cardiac remodeling and the risks of sports, including sudden death. Circulation 2006; 114(15): 1633-1644.

- Karjalainen J, et al. Lone atrial fibrillation in vigorously exercising middle aged men: case-control study. BMJ 1998; 316(7147): 1784-1785.

- Baldesberger S, et al: Sinus node disease and arrhythmias in the long-term follow-up of former professional cyclists. Eur Heart J 2008; 29(1): 71-78.

- Mont L, et al. Pre-participation cardiovascular evaluation for athletic participants to prevent sudden death: Position paper from the EHRA and the EACPR, branches of the ESC. Endorsed by APHRS, HRS, and SOLAECE. Europace 2017; 19(1): 139-163.

- Sharma S, et al: International recommendations for electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes. Eur Heart J 2017. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw631. [Epub ahead of print]

- Zipes DP, et al: Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Task Force 9: Arrhythmias and Conduction Defects: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66(21): 2412-2423.

- Andersen K, et al: Risk of arrhythmias in 52 755 long-distance cross-country skiers: a cohort study. Eur Heart J 2013; 34(47): 3624-3631.

- Biffi A, et al: Long-term clinical significance of frequent and complex ventricular tachyarrhythmias in trained athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40(3): 446-452.

- Asatryan B, et al: Sports-related sudden cardiac deaths in the young population of Switzerland. PLoS One 2017; 12(3): e0174434.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(3): 8-11