Migraine therapy has made great strides in recent years. Nevertheless, not all patients are well adjusted and are often underserved in prophylaxis. Refractory migraine can be the result – but at what point do we even talk about it?

Although migraine therapy has made great progress, some patients do not respond to guideline-based treatment [1]. In addition, some sufferers were found to be undertreated with regard to prophylactic medication, which promotes chronicity [2].

It starts with the definition

The problem starts with the clinical definition. What refractory migraine is is not conclusively understood. In 2008, the American Headache Society (AHS) presented criteria according to which, based on the primary diagnosis of ICHD-II (chronic) migraine, refractory chronic migraine (rCM) was present as soon as the headache resulted in significant limitations in function or QoL (MIDAS ≥11) despite trigger modification. In addition, rCM patients do not respond to preventive medication in at least two of four drug classes (beta-blockers, anticonvulsants, tricyclics, calcium channel blockers) during a trial period of >2 months and do not respond to triptan and DHE and either NSAIDs or combination analgesics [3]. The 2014 European Headache Federation (EHF) definition builds on the primary diagnosis of ICHD-III chronic migraine without medication overuse. Prophylactic migraine medication must have been used unsuccessfully for >3 months per drug and there is either contraindication or no effect with >3 drugs of the classes beta blockers, anticonvulsants, tricyclics, flunarizine or cardesartan, onabotulinumtoxinA; a drug is considered effective as soon as it reduces headache days by >50%. It must be possible to exclude secondary forms of headache; neither MRI nor laboratory and CSF pressure measurements may indicate other causes [4].

Dreaded crossing

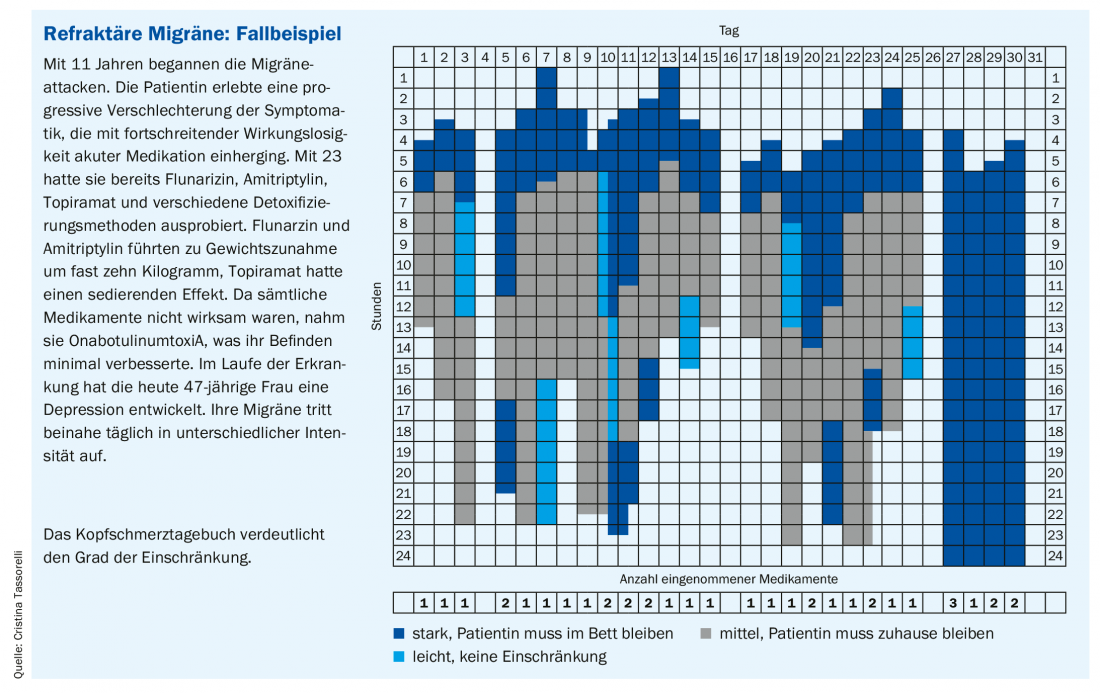

Refractory migraine is not uncommon. And yet there are few studies, which Cristina Tassorelli, MD, director of the Headache Science Centre and Neurorehabilitation Unit at the National Neurological Institute C. Mondino (IT), attributes to the inconsistent definition. In a study of 370 headache patients, 5% presented with refractory migraine, with a mean MIDAS score of 96. Younger women tend to be affected more often. Nearly 37% take medications too frequently [5].

What should be noted is the volatile nature of migraine forms: “Migraine is a dynamic disease. It varies depending on the patient and also changes within the individual,” emphasizes Tassorelli, MD. Duration and frequency vary and change throughout life. An episodic course may become a chronic course. The rate of transition from episodic to chronic migraine is 3% annually according to data from the CaMEO study [6]. Transition is not infrequently associated with the development of comorbid conditions (especially depression, chronic pain, anxiety disorders) [7]. Being out of action many days a month despite medication is an unbearable burden for those affected (case study).

Where is there a need for action?

Looking at the current mixed situation in the field of refractory migraine, from a scientific perspective, the establishment of diagnostic criteria in particular is urgently needed. Episodic and chronic forms need to be defined consistently. For example, by knowing the specific targets of treatment resistance (acute or preventive medications?), how often treatment attempts have failed, or whether medication overuse and comorbidities are present, the burden of disease can be better quantified and studied in specific trials. This includes the identification of biomarkers. Ultimately, better care could be derived from the results.

On a practical level, it is important on the one hand to highlight possible secondary factors – using a psychiatric assessment, CSF pressure measurement, MRI and testing for other medications and medication overuse – and on the other hand to make lifestyle adjustments and reduce triggers and reinforcing factors. This includes such things as normalizing sleep, weight control, regular exercise, avoiding triggers, and treating comorbid conditions. Acute therapy aims to achieve migraine-free status as quickly as possible, minimal AEs, and reduced frequency of headache. Here, Tassorelli, MD, advocates a stratified and situation-adapted approach [8] and early initiation of therapy. The use of analgesic combinations and additionally administered antiemetics may be useful.

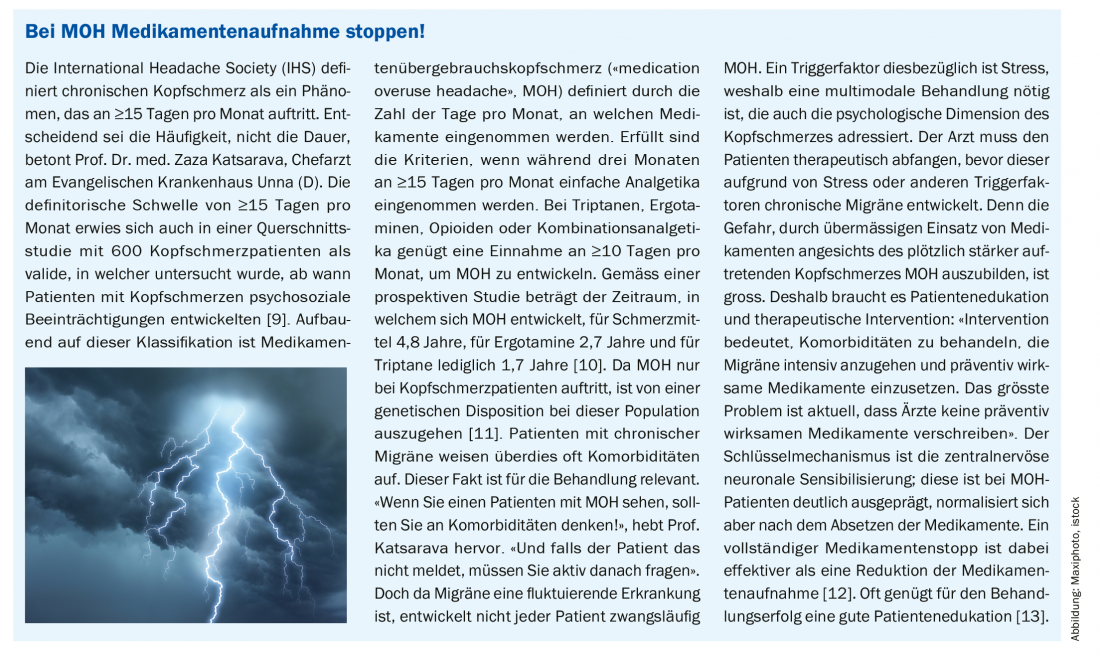

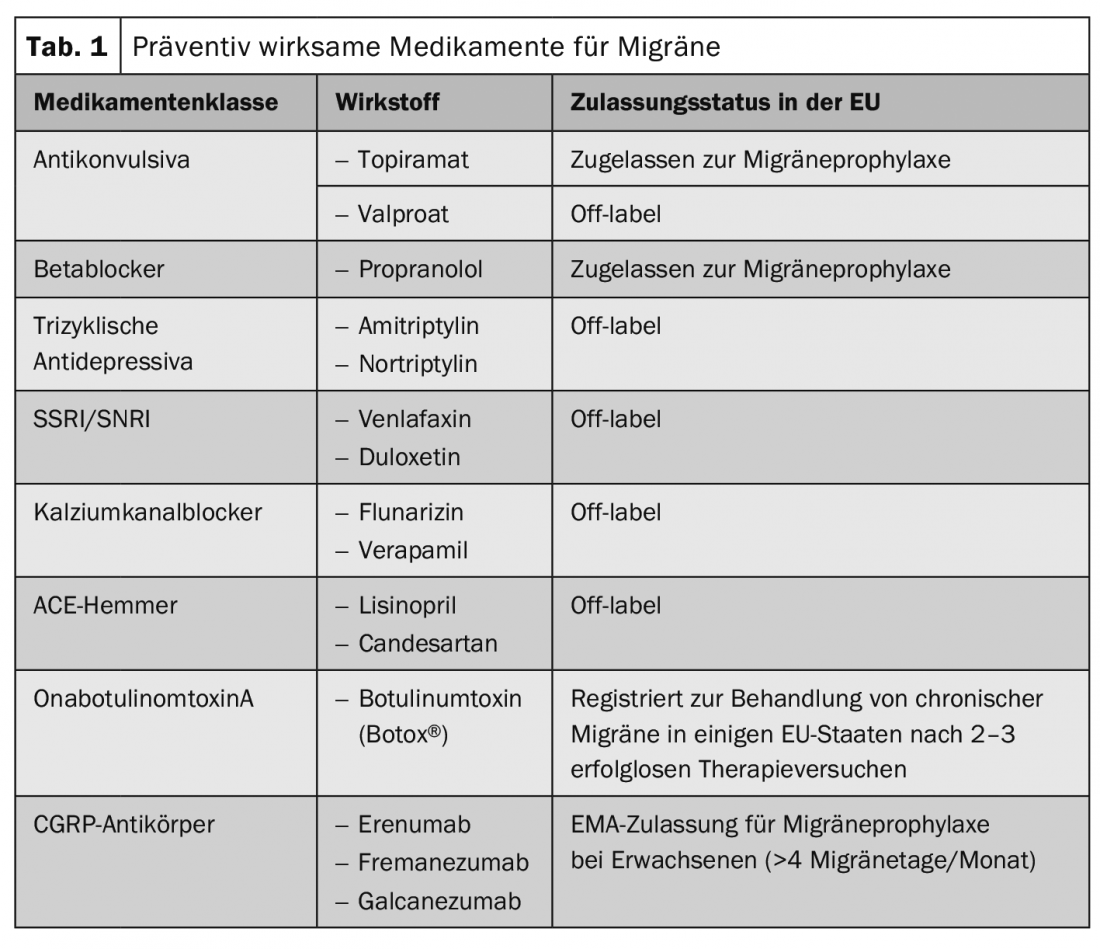

Preventive strategies aim to reduce migraine burden (frequency, intensity, duration), increase medication response, and prevent medication overuse; the latter in particular can contribute significantly to chronicity and is closely linked to the problem of refractory migraine. (Box). The prevention pillar of treatment also needs to be optimized, according to MD Tassorelli, e.g., by developing new migraine-specific medications or an escalation approach. On the one hand, this can consist of combinations of preventive drugs (Table 1). On the other hand, the use of nerve stimulators has been shown to be helpful, although the evidence is limited. Especially supraorbital nerve stimulation (stimulation of the ophthalmic nerve or the greater occipital nerve) as well as vagus nerve stimulation are well applicable, especially since both can easily be combined with medication.

Finally, the neurologist calls for a multidisciplinary approach. Patients should not only be cared for by a headache expert, but – depending on the individual situation – additionally by e.g. a psychologist or psychiatrist (also with a view to dealing with early childhood traumas that may trigger epigenetic modifications), a physiotherapist or other caregivers who contribute to patient education. The improved outcome also justifies the increased human and time resources. Last but not least, patient care includes close follow-up (every 3-4 months), which should be performed by the same physician if possible.

Source: EAN 2019, Oslo (NO)

Literature:

- Lionetto L, et al: Emerging treatment for chronic migraine and refractory chronic migraine. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2012; 17: 393-406.

- Kristoffersen ES, et al: Management of primary chronic headache in the general population: the Akershus study of chronic headache. J Headache Pain 2012; 13: 113-120.

- Schulman EA, et al: Defining refractory migraine and refractory chronic migraine: proposed criteria from the Refractory Headache Special Interest Section of the American Headache Society. Headache 2008; 48(6): 778-782.

- Martelletti P, et al: Refractory chronic migraine: a Consensus Statement on clinical definition from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain 2014; 15(1): 47.

- Irimia P, et al: Refractory migraine in a headache clinic population. BMC Neurol 2011; 11: 94.

- Adams AM, et al: The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia 2015; 35(7): 563-578.

- Buse DC, et al: Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010; 81(4): 428-432.

- Lipton RB, et al: Stratified care vs step care strategies for migraine: the Disability in Strategies of Care (DISC) Study: A randomized trial. JAMA 2000; 284(20): 2599-2605.

- Ruscheweyh R, et al: Correlation of headache frequency and psychosocial impairment in migraine: a cross-sectional study. Headache 2014; 54(5): 861-871.

- Limmroth V, et al: Features of medication overuse headache following overuse of different acute headache drugs. Neurology 2002; 59(7): 1011-1014.

- Katsarava Z, Jensen R: Medication-overuse headache: where are we now? Curr Opin Neurol 2007; 20(3): 326-330.

- Nielsen M, et al: Complete withdrawal is the most effective approach to reduce disability in patients with medication-overuse headache: A randomized controlled open-label trial. Cephalalgia 2019; 39(7): 863-872.

- Kristoffersen ES, et al: Brief intervention for medication-overuse headache in primary care. The BIMOH study: a double-blind pragmatic cluster randomized parallel controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(5): 505-512.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(8): 15-17 (published 8/22/19, ahead of print).