In view of the new and mostly well-tolerated therapies, the palliative life and treatment time of oncological patients is increasingly extended. It is a major challenge to identify patients in need of palliative support in an accurate and needs-based manner, as recommended in guidelines. In the context of Germany and Switzerland, a distinction is made between general palliative care (APV) and specialized palliative care (SPV).

In view of the new and mostly well-tolerated therapies, the palliative life and treatment time of oncological patients is increasingly extended. It is a major challenge to identify patients in need of palliative support in an accurate and needs-based manner, as recommended in international and national guidelines in terms of timely integration [1]. In the context of Germany and Switzerland, a distinction is made between general palliative care (APV) and specialized palliative care (SPV). APV is provided by the primary care team and, in the outpatient setting, usually by the primary care physician. In the inpatient sector, specialized treatment is provided by palliative services, palliative care units and hospices. Specialized outpatient palliative care (SAPV) is provided by teams that are deployed in the home environment or nursing homes. That is why there are different goals and approaches to screening for palliative care needs. It should be determined whether low-threshold, even low-specificity screening should identify both patients with general palliative care needs and those in need of specialized palliative care support (screening for palliative care needs, APV&SPV) or whether screening should specifically filter out patients in need of specialized palliative care co-management (screening for SPV needs). Screening for palliative care needs (APV&SPV) mostly uses prognostic screening to identify patients with potentially limited lifespan. Screening for SPV needs should identify non-curative patients with complex needs. Therefore, the patient group to be screened is usually specifically limited, such as to the group of non-curable or metastasized cancer patients (as operationalized in the new palliative index in the survey form for DKG certification of oncology centers).

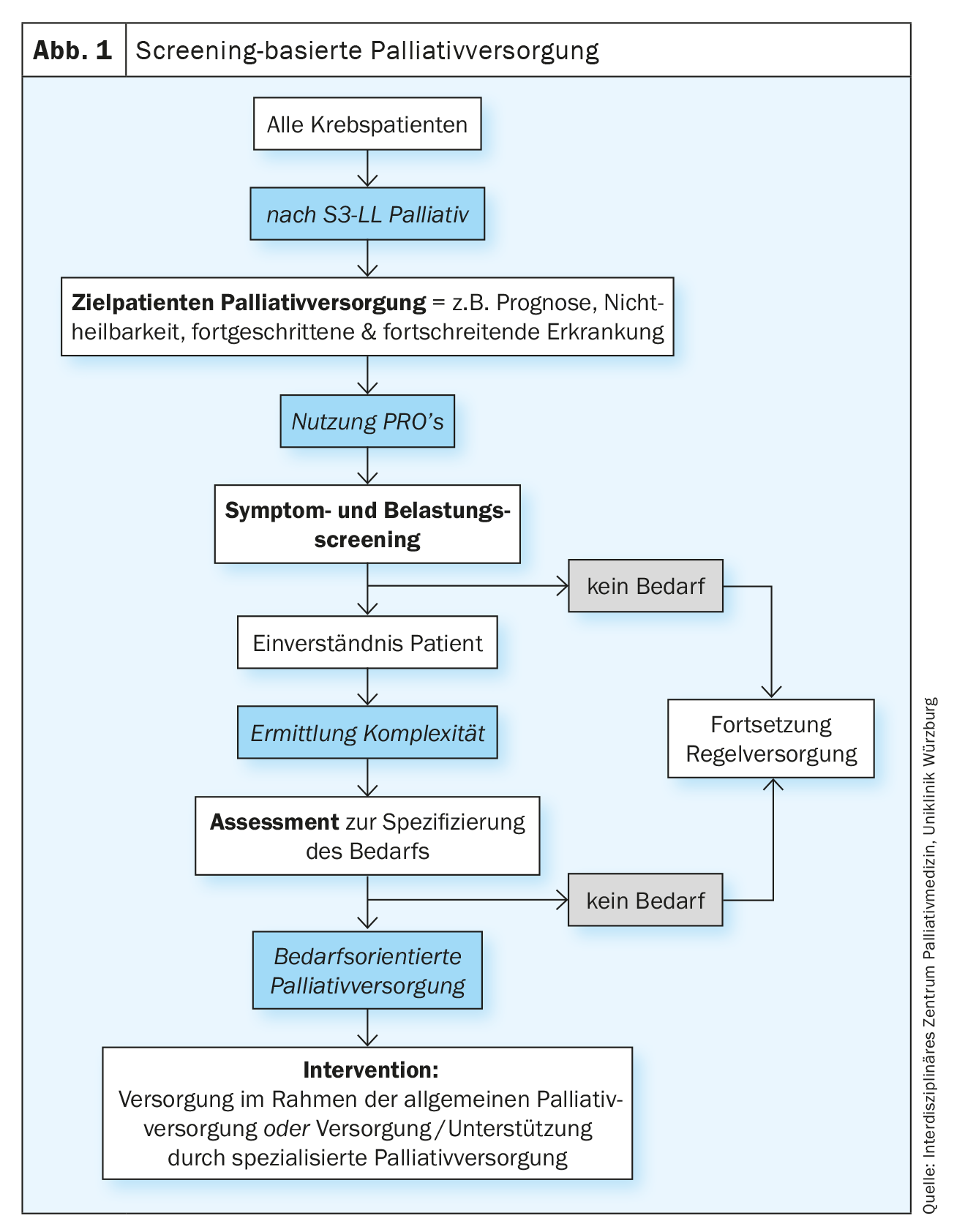

Successful screening concepts are also characterized, among other things, by an optimal pre-selection of the group of people that screening is intended to divide into high probability and low probability groups with respect to the target disease or risks. The screening procedure is usually a two-step process. In order to overlook as few potentially affected persons as possible, a sensitive but not necessarily specific test is first performed on the defined target group (screening). Screening-positive persons are assigned to the group of “ill” or “affected” persons or to the group of “non-ill” or “non-affected” persons within the framework of a specific professional clarification (assessment). The ill or affected individuals are then referred to an intervention (Fig. 1) . Screening and evaluation is usually the responsibility of primary care providers, while assessment after positive screening is then undertaken by the appropriate specialists (as recommended, for example, in psycho-oncological stress screening). Also, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for screening-based supportive and palliative care, referral to specialists is made by primary care providers after positive screening [2]. Transferred to a palliative care needs screening in oncology, this means that the screening for palliative care needs should not be performed by palliative care specialists, but by staff members of the oncology teams. The German S3 guideline Palliative Medicine for Patients with Non-Curable Cancer (S3-LL Palliative Medicine) takes up this idea in chapter 5 “Care Structures” without explicit reference to prior screening as follows: “Everyone involved in the care of patients with cancer […] should be able to identify palliative medical needs and recognize the need for palliative action in order to initiate palliative care. […] Patients should be offered a needs assessment by an SPV team after a diagnosis of noncurable advanced cancer.”, Rec. 5.8 [3].

The palliative care needs assessment is intended to assess patients with a high complexity of their overall situation in the physical, psychological, social and spiritual sub-areas in order to tailor care individually and according to need. In this context, the SNI needs assessment corresponds to the basic palliative care assessment at initial contact with the SNI, regardless of whether or not a screening was performed beforehand. The following sections will explain in more detail the various options for both palliative care needs screenings and the basic palliative care assessment.

Prognostic screening to identify patients with palliative care needs (APV&SPV).

In medicine, screenings are used to estimate survival, allowing an impression of a disease pattern or injury pattern in a short time using comparable parameters. Prognostic screenings can also be used to identify patients in need of palliative care and, if appropriate, end-of-life care. Several tools are available to estimate temporal prognosis in patients with advanced cancers. The state of knowledge was last reported in 2019 in a review by Hui et al. rehashed [4]. In light of the prognosis-based recommendations for identifying patients with palliative care needs (APV&SPV), the tools for identifying patients with an expected survival of 6-12 months and for identifying dying patients are particularly relevant, i.e., patients with an expected survival of 3-7 days or less. Probably the oldest instrument is the so-called “Surprise Question,” i.e., the question: “Would you be surprised if this patient died within the next 12 months?” The answer: “No, I would not be surprised” indicates the limited prognosis. The Surprise question is varied many times in terms of the survival time to be estimated (“hours”, “days”, “weeks”, “6 months”, …). Van Lummel et al. analyzed 59 studies in a recent review and found a sensitivity of 71.4% (95% CI 66.3-76.4) with a specificity of 88.6% (95% CI 69.3-78.6) for the original surprise test. In contrast to previous analyses, there was no difference depending on the profession of the assessor (medical staff vs. nurses). Even with highly variable mortality rates, the negative predictive value was high [5].

In further prognosis screenings, which have also been developed for advanced cancer patients, mostly disease- and history-related parameters as well as clinical items such as functional status, mobility or food intake are combined, sometimes supplemented by relevant clinical symptoms such as shortness of breath or loss of appetite. The individual parameters are weighted differently in some cases. When added together, this results in point values that are backed by percentages for expected e.g. 6-month or 4-week survival [6]. Various prognostic screenings have been developed in specific settings, such as radiation therapy, family medicine, or specialized palliative care, or are recommended for specific clinical situations, such as hospital admission. Kirkland et al. Analyzed 35 publications with 14 instruments to screen for palliative care needs in emergency departments. The most widely used instrument was the Surprise-Question, followed by the Palliative Care and Rapid Emergency Screening tool (P-CaRES) and the Screening for palliative and end-of-life care needs in the emergency department SPEED instrument. The median sensitivity was 63% (IQR 16-40%) and the specificity was 75% (IQR 57-84%). The median negative predictive value was high (91%). Between 5% and 85% of patients had palliative care needs [7]. A new and resource-efficient approach is the use of routine data. Gensheimer et al. developed a promising prognosis estimation model using the electronic medical records of 12 588 metastatic cancer patients, which is currently being tested prospectively [8].

Prognostic screenings are intended to sensitize treating teams to the potentially very limited lifespan of their patients and to help identify the need for palliative action and initiate palliative care (APV&SPV) when appropriate. This is also useful and possible concurrently with causal therapy. Research shows that approximately 60% of physicians significantly overestimated the prognosis of patients with advanced tumors, and only 5% underestimated the remaining life span. A team-approach based on the Surprise question or the use of standardized screening instruments can contribute to a more realistic situation assessment of all parties involved and help to adjust therapy goals and treatment plans, optimize symptom relief, review the level of education and information of patients and close relatives, (re)address the possibilities for advance health planning, and adjust the care concept if necessary. In this context, the need for specialized palliative care should then also be clarified.

Screening with patient self-assessment questionnaires (PROs, APV&SPV).

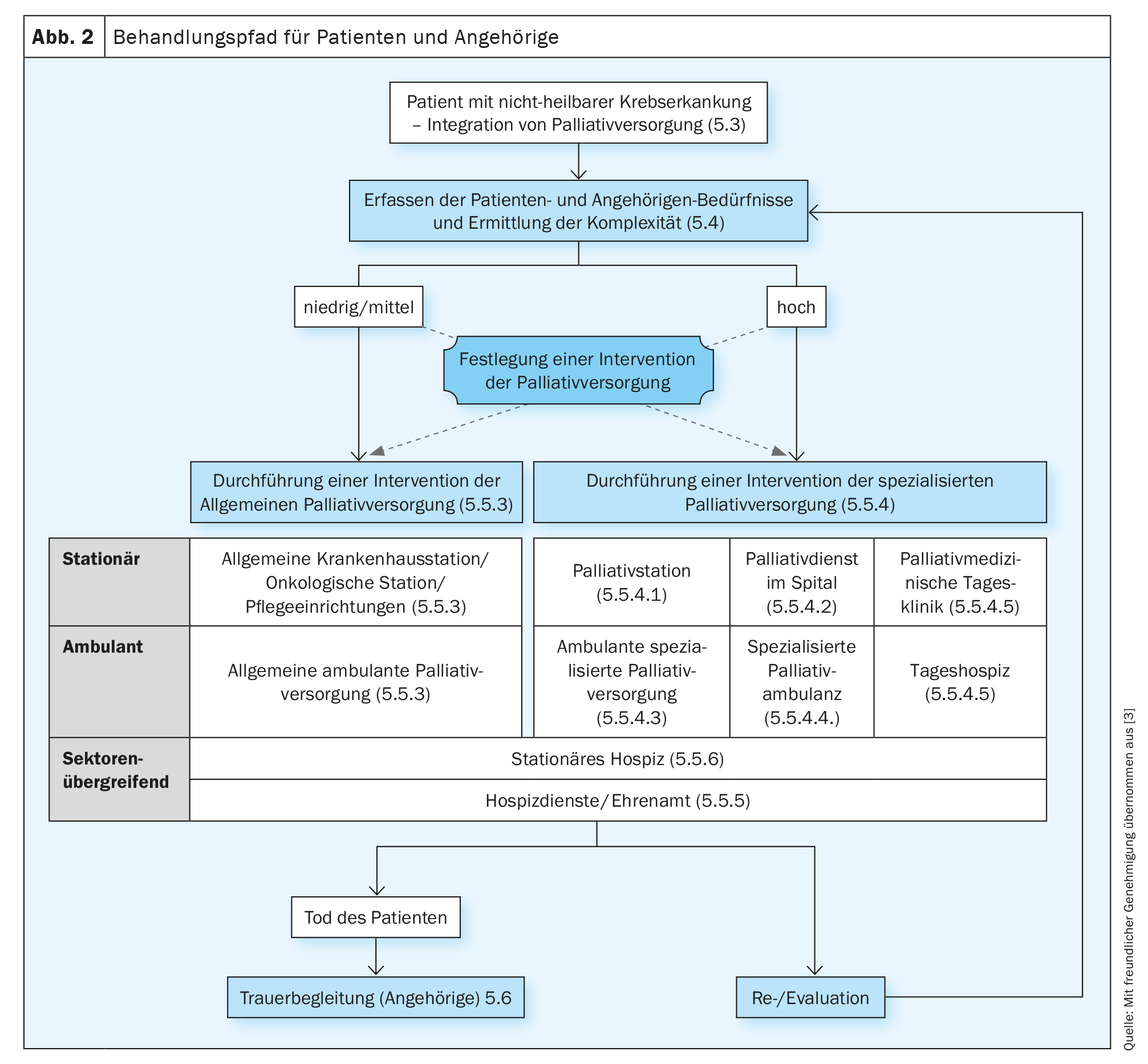

The S3-LL Palliative Care for Noncurable Cancer Patients recommends repeated assessment of symptoms, distress, and information needs so that treatment goals and the individual treatment plan can be adequately adjusted. Validated multidimensional recording instruments should be used for this purpose (S3-LL Palliative Medicine, Rec. 5.5), ideally self-assessment questionnaires (Patient Reported Outcome instruments, PROs). The S3-LL Palliative Medicine does not explicitly speak of screening at this point, but of a needs assessment by the SNI, in which the complexity of the situation is to be assessed in addition to symptoms, needs and burdens. Although the needs assessment does not necessarily have to be conducted by specialized palliative care (SPV) staff, the criteria for requesting specialized palliative care intervention must be established by the specialized palliative care (SPV) staff. A corresponding algorithm can be found in the S3-LL Palliative Medicine (“Treatment pathway for patients and relatives”, p. 47 S3-LL Palliative Medicine, Fig. 2). The need for specialized palliative care support should be assessed based on complexity. When determining complexity, patient and family needs, functional status, and disease phase should be considered (Rec. 5.7, S3-LL Palliative Medicine). The complexity rating differentiates between “low/medium” and “high”. Patients with low/medium complexity should receive general palliative care interventions (APV, estimated 70-80% of all patients) and high-complexity patients should receive specialized palliative care (SPV, estimated 20-30% of patients).

The gold standard for recording symptoms, stresses, and problems are self-assessment questionnaires (PROs), in which patients document their concerns without other “intermediaries.” In external assessment (both by professionals and by loved ones), there are often misjudgments, both underestimation and overestimation of symptoms and distress. Hart et al. in a recent review, identified 81 studies from 2002-2022 on unmet needs of patients with solid tumors and hematologic diseases with advanced disease who require noncurative therapy and their loved ones [9]. The researchers identified six dimensions to which the unmet needs of the four affected groups could be assigned (see. in detail in Table 1) . 5/81 studies with 962/19 382 patients were conducted in German-speaking countries (6.1% of studies with 4.9% of patients), so the results are not necessarily transferable. The differentiation of the domains seems extremely helpful for the further development of the collaboration of the supportive disciplines.

Analogous to the psycho-oncological stress screening established in DKG-certified centers, palliative care self-assessment questionnaires are now also used to screen for palliative care needs, sometimes in combination with the recommended psycho-oncological patient self-assessment questionnaires [10]. Because PROs also factor into the assessment of complexity, symptom and distress screening with palliative care self-assessment questionnaires not only helps raise awareness of patient concerns among primary care providers, but also supports needs-based referral for specialized palliative (co-)care. It is the subject of current discussions and research projects how palliative care self-assessment questionnaires can be optimally used also for the identification of patients with need for specialized palliative care co-management (SPV need).

To assess patients’ problems and needs, the S3-LL Palliative Care recommends four validated self-assessment instruments as examples: the Minimal Documentation System (MIDOS-2 [11]), the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS/revised version ESAS-r [12]), the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS [13]), and the Distress Thermometer with Problem List [14]. Since the MIDOS-2 is in the German validated version of the ESAS-r, the number is reduced to three recommended instruments. Surprisingly for the reader, only MIDOS and IPOS instruments are recommended for the recording of the quality indicator related to the mentioned recommendation 5.5 (QI10, as often as possible symptom recording using MIDOS or IPOS in patients with non-curable cancer). It is possible that ambiguity should be avoided, as the distress thermometer is already recommended in the 2015 S3 guideline Psychooncology as a screening tool to assess the need for psycho-oncological treatment. On the other hand, this duplication also opens up the opportunity of a resource-saving coordinated approach and the use of synergies for the future.

In the multicenter piloting of the new metric “Symptom recording with MIDOS/IPOS in non-curable cancer patients” (KeSBa project [10]), the MIDOS was used more frequently than the (younger) IPOS in DKG-certified oncology centers. A strength of the MIDOS is a simple graduation to record the severity of ten physical/psychological symptoms (none, mild, moderate, severe) and a question about how well you feel (very bad, bad, moderate, good, very good). A strength of the IPOS – in addition to its proven sensitivity to change [13] – is its focus on the burden of the symptoms and problems asked about, based on the assumption that what matters for symptom relief is not symptom intensity but the impact on the patient (“burden”). Furthermore, in addition to respondents’ burden of ten physical/psychological symptoms, the IPOS also captures the burden of, among other things, relatives’ concern, insufficient information, and unresolved practical problems.

Basic palliative care assessment

Through the structured palliative care baseline assessment (PBA), the specific needs of a palliative care patient should be mapped in all dimensions. In Germany, the PBA is based on the recommendations of the professional society DGP (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin e.V.), and the definition of OPS 1-774 (“standardized basic palliative care assessment”). The PBA can be performed both as a palliative care assessment after positive screening or as part of the initial palliative care assessment after physician-triggered referral to specialized palliative care. In the PBA, in addition to a detailed medical history, the patient’s individual and current life situation is also recorded. Since palliative care does not only pay attention to physical dimensions, at least five dimensions/areas of palliative care should be surveyed in the PBA. These include symptom intensity, psychosocial distress, the degree of self-help ability, the extent of the patient’s social involvement, and the patient’s social situation and daily living skills. The survey of these areas is carried out using standardized measurement procedures incl. Patient self-assessment forms recommended. Thus, if MIDOS or IPOS have already been used in screening, they can also be used as part of PBA (if screening and PBA are done in a timely manner). The DGP provides a selection of recommended further instruments on its website. It should be noted that not every area has to be surveyed with a separate instrument, but that multidimensional instruments can also be used. The meaningful composition of a PBA should ideally reflect not only the patient’s baseline situation, but also his or her care needs and (expected) effort of the treating team. In addition, the data collected should also be usable for quality assurance, comparability, evaluation, and research, and ultimately meet an accrued compensation claim.

In summary, structured symptom and needs assessment in cancer patients is useful and also highly recommended in terms of patient empowerment. Effectiveness in terms of patient-reported outcome criteria can be expected when symptom and distress recording is complemented by lived algorithms for the approach – ideally coordinated with the other supportive disciplines – to screening-eligible patients [10]. Palliative care questionnaires contribute to a broader understanding of patient concerns by recording physical symptoms and focusing on family members’ concerns, information needs, spiritual aspects, and practical problems, thus complementing psychosocial distress screening. The basic palliative care assessment is used for multidimensional assessment of the support and care needs of patients in specialized palliative care. Because the recommended self-assessment tools are recommended for both screening and palliative care assessment, it is straightforward to follow up on screening in the assessment. Single-item level treatment recommendations for patient care in specialized outpatient palliative care (SAPV) have been published for IPOS.

Take-Home Messages

- The estimation of the prognosis (prognosis screening) is helpful in order to

Identify patients with potential palliative care needs in a timely manner. - Palliative care involves an anticipatory approach to care, focusing treatment on quality of life, symptom relief, and support for those close to the patient (informal caregivers).

- Identifying patients with palliative care needs and initiating palliative care is the responsibility of the primary care teams (general palliative care).

- The involvement of specialized palliative care should be based on the complexity of the patient’s situation.

- To assess complexity, patient and family needs should be assessed with self-assessment questionnaires (PROMs), supplemented by functional status and disease phase.

Literature:

- Hui D, et al: Timely Palliative Care: Personalizing the Process of Referral. Cancers 2022; 14(4).

- Riba MB, et al: Distress management, version 3.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019; 17(10): 1229-1249; doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0048.

- Oncology guideline program (German Cancer Society, German Cancer Aid, AWMF): palliative care for patients with noncurable cancer, long version 2.2, 2020, AWMF registry number: 128/001OL, www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/palliativmedizin/ (retrieved on: 05/14/2023).

- Hui D, et al: Prognostication in advanced cancer: update and directions for future research. Support Care Cancer 2019; 27(6): 1973-1984; doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04727-y.

- Van Lummel EV, et al: The utility of the surprise question: A useful tool for identifying patients nearing the last phase of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliative Medicine 2022; 36(7): 1023-1046; doi: 10.1177/02692163221099116.

- Ueno Y, Kanai M: Prognosis Prediction Models and their Clinical Utility in Palliative Care 2017; www.intechopen.com/bookshighlights-on-several-underestimated-topics-in-palliative-care/prognosis-prediction-models-and-their-clinical-utility-in-palliative-care (retrieved on: 2/18/2021).

- Kirkland SW, et al: Screening tools to identify patients with unmet palliative care needs in the emergency department: A systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2022; 29(10): 1229-1246; doi: 10.1111/acem.14492.

- Gensheimer MF, et al: Automated Survival Prediction in Metastatic Cancer Patients Using High-Dimensional Electronic Medical Record Data. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 2019; 111(6): djy178; doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy178.

- Hart NH, et al: Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: A systematic scoping review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2022; 176: 103728; doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103728.

- Braulke F, et al: Systematic symptom screening in patients with advanced cancer treated in certified oncology centers: results of the prospective multicenter German KeSBa project. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023; doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-04818-8.

- Bruera E, et al: The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991; 7(2): 6-9.

- Stiel S, et al: Validation of the new version of the minimal documentation system (MIDOS) for patients in palliative care: the German version of the edmonton symptom assessment scale (ESAS). Pain 2010; 24(6): 596-604.

- Murtagh FE, et al: A brief, patient- and proxy-reported outcome measure in advanced illness: validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS). Palliat Med 2019; 33(8): 1045-1057.

- Mehnert A, et al: The German version of the NCCN Distress Thermometer. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2006; 54(3): 213-223.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(9): 10-14