The most common causes of halitosis are tongue coating or gingivitis. Blanket and blind therapies usually lead to failure, which is why treatment should be strictly cause-related.

Due to increasing media presence and a rise in scientific studies, the taboo subject of bad breath has become the focus of patients and physicians in recent years. Nevertheless, halitosis is still a widespread problem. About 10-40% of the population have halitosis at least some of the time [1,2,3]. Before patients visit a professional halitosis consultation, more than half have already seen one or more physicians [4]. This shows that in practice there is a certain helplessness in dealing with such patients. Often blanket therapies are performed without success, which takes a lot of time as well as costs and ultimately leads to frustration of the patient and practitioner. Not infrequently, gastrointestinal endoscopies as well as tonsillectomies are performed or an antibiotic is prescribed, all without success. Many patients suffer from halitosis for several years, which becomes an increasing psychological burden and can greatly reduce the quality of life of those affected [4].

This article provides an overview of the complex topic of halitosis. For a deeper insight, reference is made at this point to the book “Halitosis. Professional treatment of halitosis in dental practice” [5].

Terminological differentiations

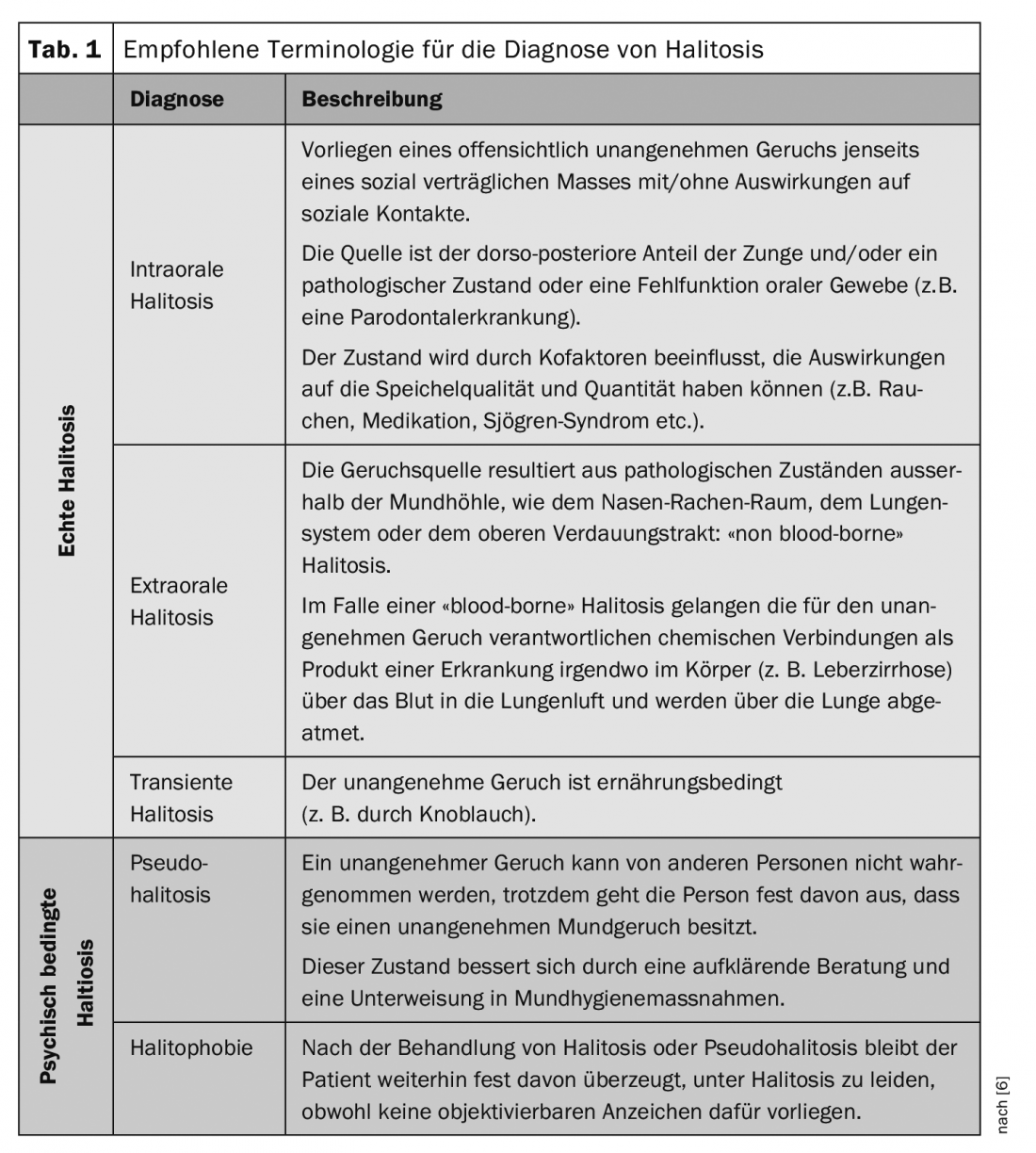

Halitosis is derived from the Latin word halitus (breath, haze) and describes an unpleasant smelling breath independent of the place of origin. Synonymously used terms such as halitosis or foeter ex ore refer only to cases with a cause in the oral cavity. In order to include all clinical pictures as far as possible, only the term halitosis should be used today. Depending on the origin, a distinction is made between intraoral and extraoral halitosis. In addition to this true halitosis, there is also psychologically induced halitosis (pseudohalitosis/halitophobia). The patient describes an unpleasant odor, which cannot be confirmed objectively or with measuring instruments. Patients with pseudohalitosis, unlike patients with halitophobia, can be convinced that halitosis is not present through appropriate diagnosis and education. Transient halitosis is caused by foods such as onion or garlic [6] (Table 1).

Causes mostly localized in the oral cavity

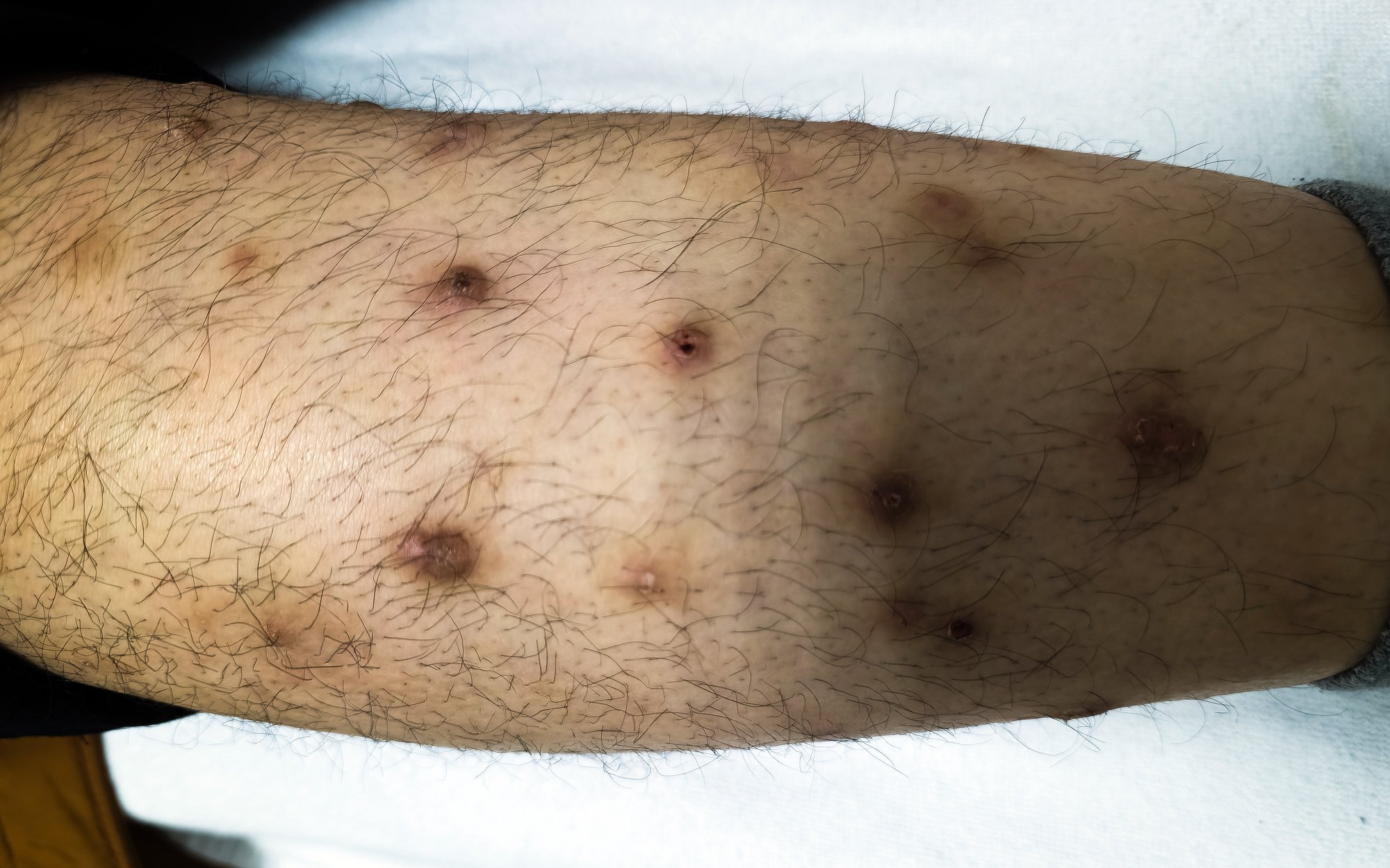

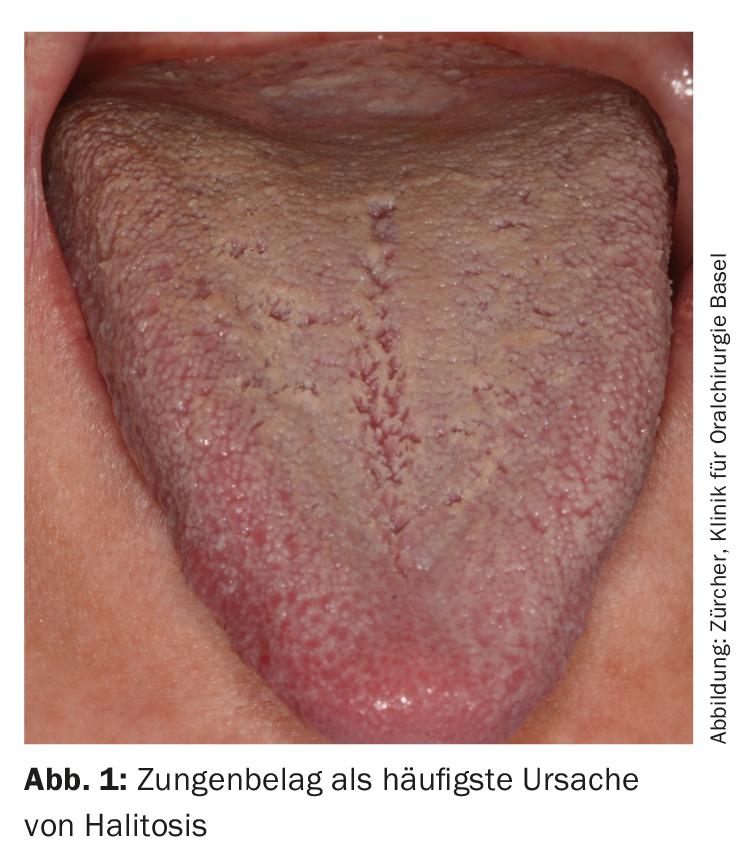

Various studies showed that the source of the unpleasant odor is in the oral cavity in about 80-90% [4,7]. Because more than half of oral bacteria are localized on the tongue surface, the dorsum of the tongue in combination with tongue coating (Fig. 1) is the most common cause of halitosis. Gram-negative, anaerobic bacteria, which reside in the oxygen-protected microfurrows and crevices of the tongue epithelium, metabolize organic material from saliva, food debris, and sloughed-off epithelial cells. Proteins containing sulfur-containing amino acids (e.g., cysteine, cystine, and methionine) are converted to volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) and enter the air we breathe. In halitosis, hydrogen sulfide, methyl mercaptan, and the somewhat less volatile dimethyl sulfide play the most important roles [8]. The special bacteria are also responsible for inflammation of the gums (gingivitis) and periodontium (periodontitis marginalis), which are other possible oral causes in addition to poor oral and denture hygiene and local infections [4,5,7].

Contrary to the still widespread opinion, causes outside the oral cavity are rather rare, accounting for about 5% of cases [4,7]. Most commonly, these are in the ear, nose, and throat (e.g., tonsillitis, maxillary sinusitis), followed by the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux, diverticula). Systemic diseases, metabolic and hormonal changes, hepatic or renal insufficiencies, and respiratory diseases may also be responsible for halitosis [5]. Recent studies revealed evidence that a genetic defect in SELENBP1 can lead to cabbage-like body odor [9].

Furthermore, so-called cofactors also play an important role, as they can promote the development of oral halitosis. Reduced salivary flow rate is the most important cofactor, for which there are many different causes. For example, many patients take medications that cause dry mouth as a side effect. This changes not only the quantity but also the quality of saliva: it becomes more viscous and sticky. In a dry oral cavity, the rinsing and diluting effect of saliva is greatly reduced, which promotes biofilm formation. Smoking, coffee and alcohol consumption, low daily water intake, mouth breathing, unbalanced diet and too high or too low body mass index can also promote the development of halitosis [5].

Diagnosis and therapy concept at a glance

Prior to the appointment, the patient receives a four-page medical history form (www.andreas-filippi.ch). This serves as the basis for the introductory discussion with the patient and provides information about the type and frequency of halitosis, self-therapies already performed as well as treatments with other physicians and the level of suffering. With this general and specific history, possible co-factors are also recorded. This is followed by a clinical assessment with the aim of identifying predilection sites in the oral cavity. This is followed by an inspection of the oral and pharyngeal soft tissues (especially tongue coating, Waldeyer’s pharyngeal ring, salivary gland excretory ducts). Furthermore, dental fillings and restorations, periodontal conditions and oral hygiene are assessed [4,5]. If the patient complains of dry mouth or if this could be confirmed during the examination, a saliva test (Saliva-Check BUFFER®, GC) is also performed. Microbiological examinations, on the other hand, are rarely used because they basically have no influence on therapy [5].

Breath diagnostics are performed organoleptically (using the handler’s sense of smell) and with measuring instruments [4-6, 10-12]. During the introductory interview and clinical examination, the severity of halitosis is recorded depending on the distance from the examiner to the patient (distance 1 m=grade 3, distance 30 cm = grade 2, distance 10 cm = grade 1) [4,5,12].

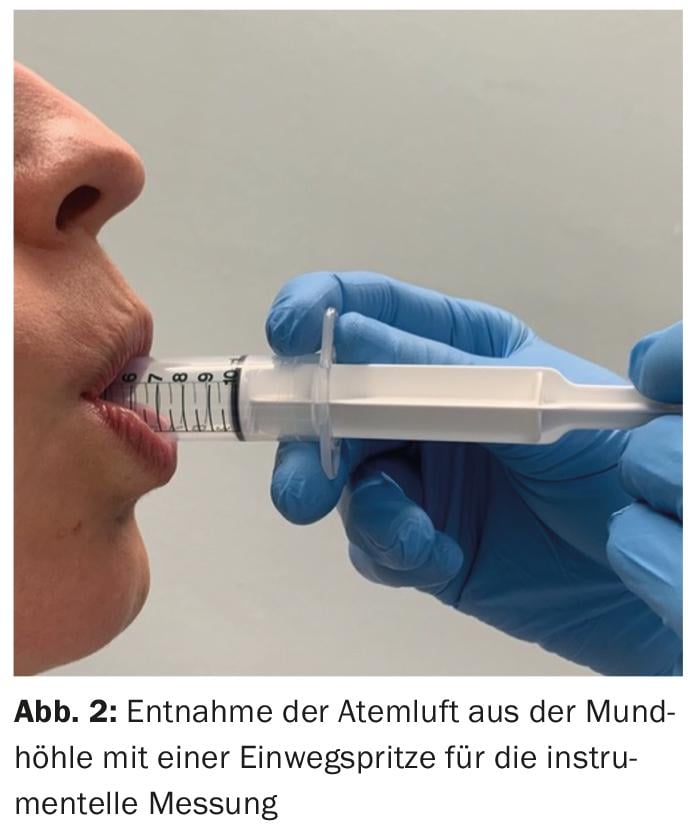

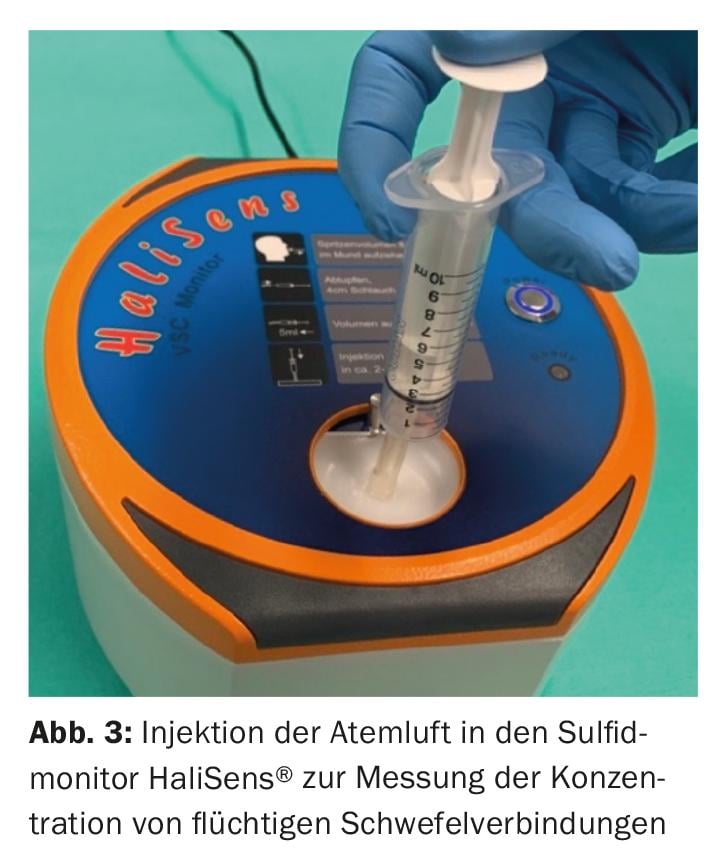

The instrumental measurement is performed with a sulfide monitor (HaliSens®, Al Analytical Innovations GmbH, Moosbach, Germany) (Fig. 2 and 3) and a gas chromatograph (OralChroma™, Fa. Abilit, USA). This objectifies the patient’s olfactory symptoms and shows the distribution of volatile sulfur compounds [4,5,11,12].

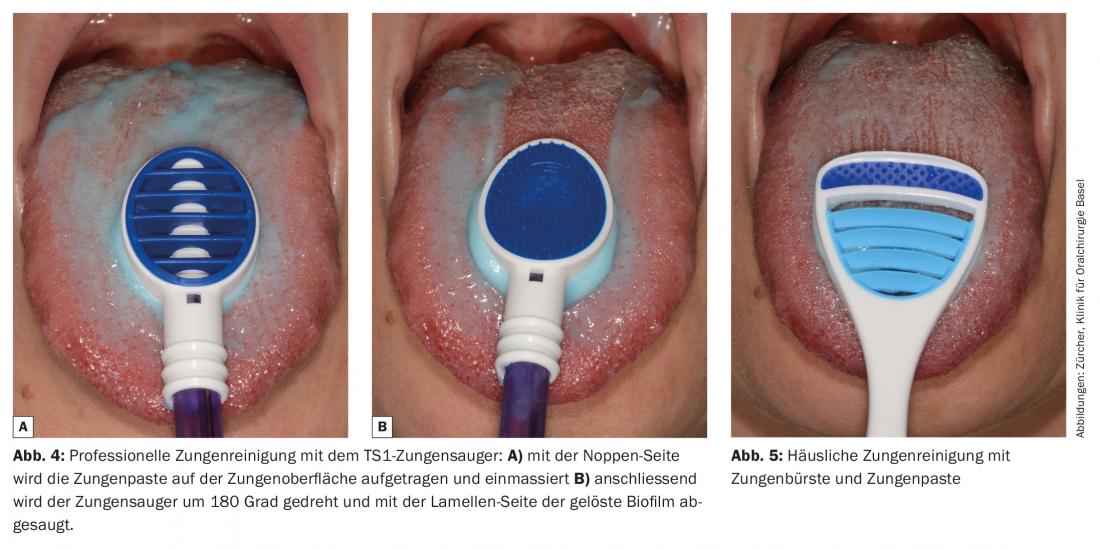

Depending on the cause, the individual therapy concept is discussed with the patient: Existing inflammations of the gums or periodontium and carious lesions are treated, if necessary with dental hygiene support. If the back of the tongue is covered with tongue coating, professional tongue cleaning is performed with the TS1 tongue aspirator (TS Pro GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany): The biofilm on the tongue surface is loosened with a tongue paste and with the two functional sides of the tongue suction device (nap side and suction side) and suctioned off [13] (Fig. 4a and 4b). In addition, the patient is introduced to home tongue cleaning with a tongue brush and tongue paste as part of the daily oral hygiene routine [4,5,12] (Fig. 5). If cofactors are present, they are discussed with the patient and corrected if possible. Consult with the primary care physician or attending physician as needed [4,5,12].

If the cause of halitosis is outside the oral cavity or if the patient suffers from halitophobia, he is referred to the appropriate specialist (ear, nose and throat specialist, internist, psychologist/psychiatrist) [4,5].

Additionally, the Halitosis app is recommended [14]. This allows the patient to read the information received at their leisure. In addition to many pictures, there is also a video tutorial that shows a reliable self-test. With an interactive diary, the user can become even more involved with the topic.

Conclusion

There is no blanket therapy for the treatment of halitosis. Only a strictly cause-related procedure leads to success. The therapy concept of the halitosis consultation at the UZB University Dental Clinics was repeatedly adapted during 16 years, so that a consistently high therapy success of over 90% could be achieved. This shows that today no one should suffer from halitosis.

Literature:

- Miyazaki H, et al.: Correlation between volatile sulphur compounds and certain oral health measurements in the general population. J Periodontol 1995; 66 (8): 679-684.

- Loesche WJ, et al: Oral malodour in the elderly. In: Van Steenberghe D, Rosenberg M (eds). Bad breath. A multidisciplinary approach. Leuven: University Press, 1996: 181-195.

- Bornstein MM, et al: Prevalence of halitosis in the population of the city of Bern, Switzerland: a study comparing self-reported and clinical data. Eur J Oral Sci 2009; 117(3): 261-257.

- Zürcher A, et al: Findings, diagnoses, and outcomes of a halitosis consultation over a seven-year period. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2012; 122(3): 205-216.

- Filippi A: Halitosis. Berlin: Quintessenz, 2011.

- Seemann R, et al.: Halitosis management by the general dental practitioner-results of an international consensus workshop. Swiss Dent J 2014; 124(11): 1205-1211.

- Quirynen M, et al: Characteristics of 2000 patients who visited a halitosis clinic. J Clin Periodontol 2009; 36(11): 970-795.

- Tonzetich J: Production and origin of oral malodor: a review of mechanisms and methods of analysis. J Periodontol 1977; 48(1): 13-20.

- Pol A, et al: Mutations in SELENBP1, encoding a novel human methanethiol oxidase, cause extraoral halitosis. Nat Genet 2018; 50(1): 120-129.

- Greenman J, et al: Organoleptic assessment of halitosis for dental professionals-general recommendations. J Breath Res 2014; 8(1): 017102.

- Laleman I, et al: Instrumental assessment of halitosis for the general dental practitioner. J Breath Res 2014; 8(1): 017103.

- Schumacher MG, et al: Evaluation of a halitosis consultation over a period of eleven years. Swiss Dent J 2017; 127(10): 852-856.

- Zürcher A, et al: A new instrument for professional tongue cleaning. Quintessenz 2016; 67(6): 729-733.

- Filippi A: Smartphone apps for dentists. Swiss Dent J 2018; 128(3): 252.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(4): 30-33