With the publication of the new European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension, there has been some movement away from strict recommendations toward more flexibility and simplification in the care of patients with arterial hypertension. Thus, blood pressure measurement outside the doctor’s office and hospital is becoming much more important. A blood pressure of <140/ 90 mmHg should be aimed at as a largely uniform therapy target value. In elderly patients, a blood pressure reduction below 160 mmHg systolic is often sufficient. In addition, the new guidelines reemphasize the central importance of individual cardiovascular risk stratification. This should not only include information on cardiovascular risk factors, but also a targeted search for pre-existing end-organ damage or manifest cardiovascular and renal diseases. The results of risk stratification serve as the basis for decision-making regarding the best possible therapeutic strategy and choice of drug therapy.

With a prevalence of 30-45%, arterial hypertension remains the main risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the European population [1]. On the occasion of the “23rd European Meeting on Hypertension & Cardiovascular Protection” in Milan, the new joint guidelines of the European Societies of Hypertension (ESH) and Cardiology (ESC) on the diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension were presented [1]. The guidelines, developed by 40 European reviewers over 18 months, continue to emphasize the paramount importance of early diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension. At the same time, however, there has been some movement away from strict to more flexible recommendations in the care of patients with arterial hypertension. Even more than before, the guidelines emphasize using overall cardiovascular risk as a key decision criterion for initiation and type of treatment. Another important focus is the treatment of arterial hypertension in special patient groups. The aim of this overview is to highlight the most important clinically relevant innovations and changes.

UPDATE: Blood pressure measurement and forms of hypertension

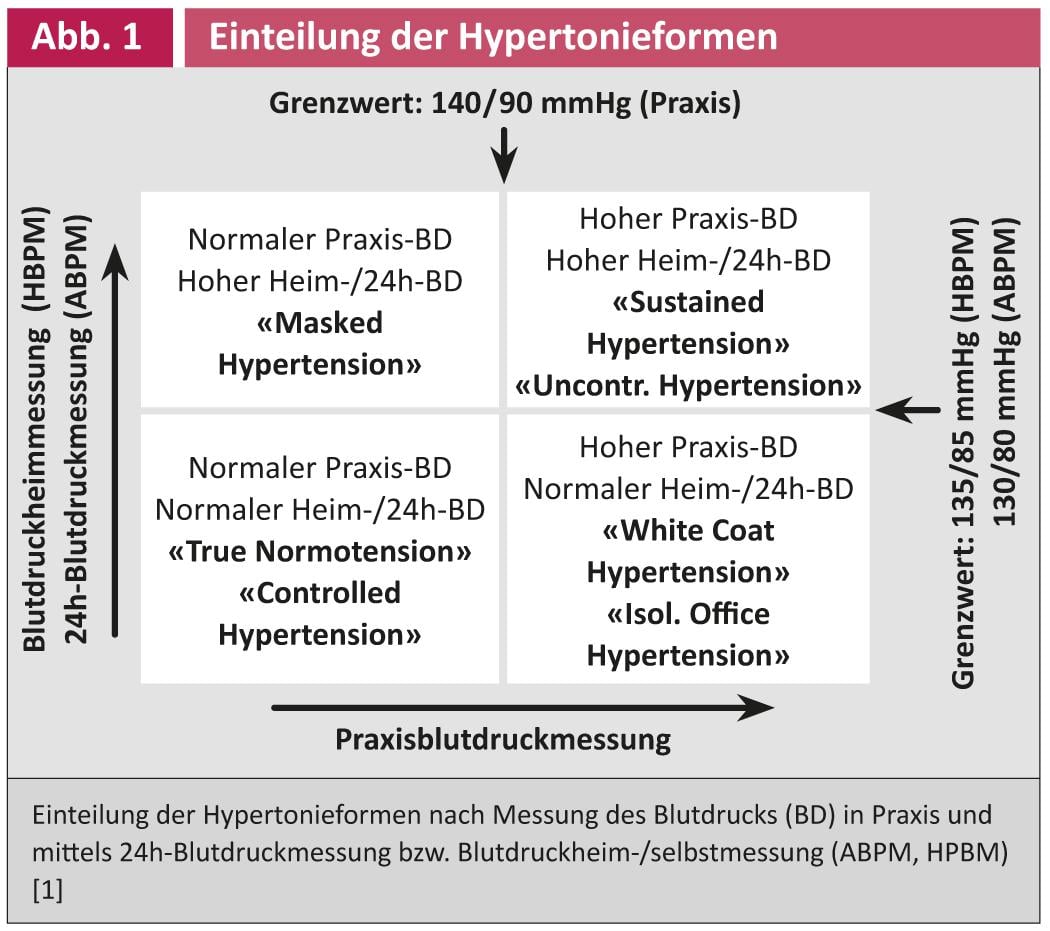

Repeated office blood pressure measurements remain the gold standard for the diagnosis of arterial hypertension. However, out-of-office blood pressure measurement – 24h blood pressure measurement or blood pressure self-monitoring – is rapidly gaining importance, not least because of health economic advantages [2] and because of the greater involvement of patients in the control of arterial hypertension [3]. Furthermore, it is only the measurement of blood pressure outside the practice that makes the diagnosis of certain forms of hypertension possible at all. Here, of course, the so-called white coat hypertension (“White Coat Hypertension”, elevated blood pressure in, but normal blood pressure outside of practice or hospital), but also the “masked arterial hypertension” (“Masked Hypertension”, normal blood pressure in, but elevated blood pressure outside of practice or hospital) should be mentioned (Fig. 1).

While the prognostic significance of white coat hypertension is still not conclusively established, it is assumed with regard to masked arterial hypertension that this form of arterial hypertension is comparable to permanently elevated blood pressure in terms of the associated cardiovascular risk [4].

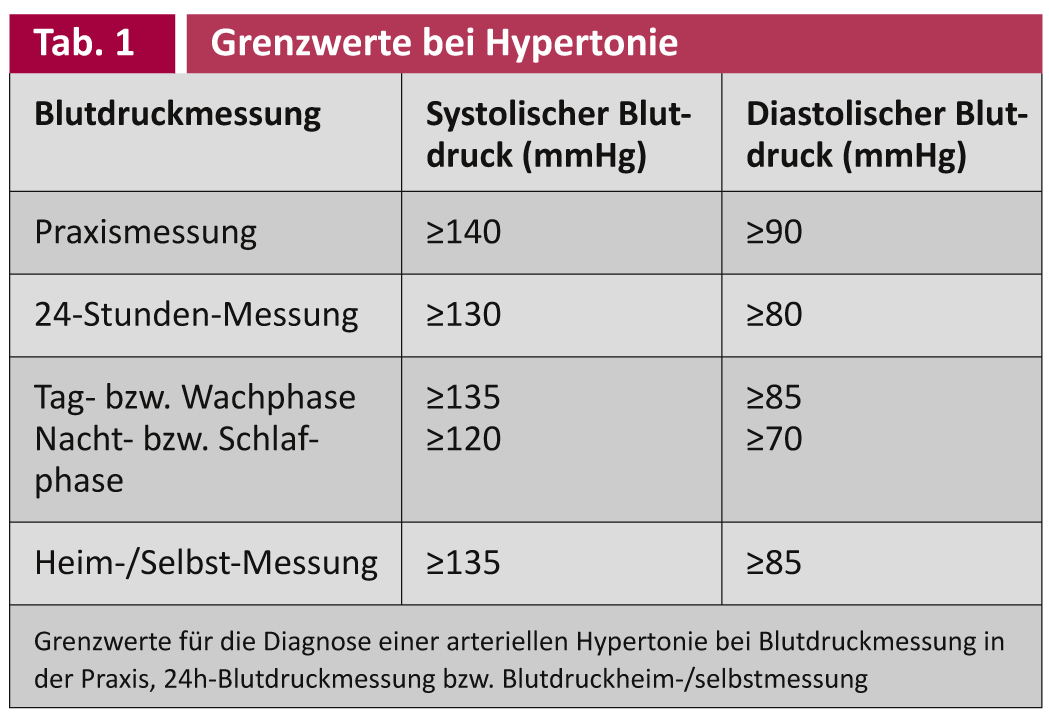

Also with regard to the decision for or against an antihypertensive therapy or the decision about changes in therapy, both 24h blood pressure measurement and blood pressure self-measurement are often more target-oriented than practice blood pressure measurement; they additionally complement the risk stratification of the patient. In many situations, these methods are therefore recognized as an alternative to office blood pressure measurement (exceptions: Clarification of nocturnal hypertension, determination of the “dipping” status and blood pressure variability). However, it should be noted that both 24h blood pressure measurement and blood pressure self-measurement have different limits compared to practice blood pressure measurement (Table 1) [1].

UPDATE: Risk stratification

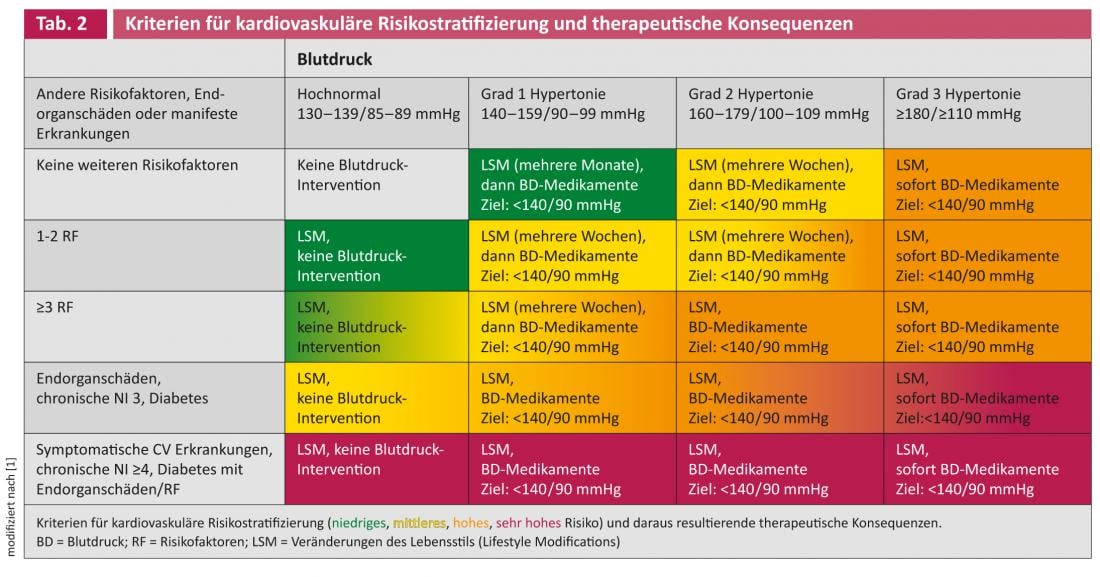

The decision regarding the initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy and the therapeutic strategy should take into account not only the level of blood pressure, but very significantly the patient’s individual overall cardiovascular risk. Known cardiovascular risk factors such as age, smoking status, abdominal girth or body mass index, blood glucose and cholesterol levels, and physical inactivity are used to determine this individual risk. With appropriate risk scores, such as the Euro-SCORE [5], the individual cardiovascular risk can be estimated by including these parameters. Despite being easy to use, these scores have a major disadvantage: they do not include existing subclinical end-organ damage or the presence of manifest disease in the risk assessment (Table 2).

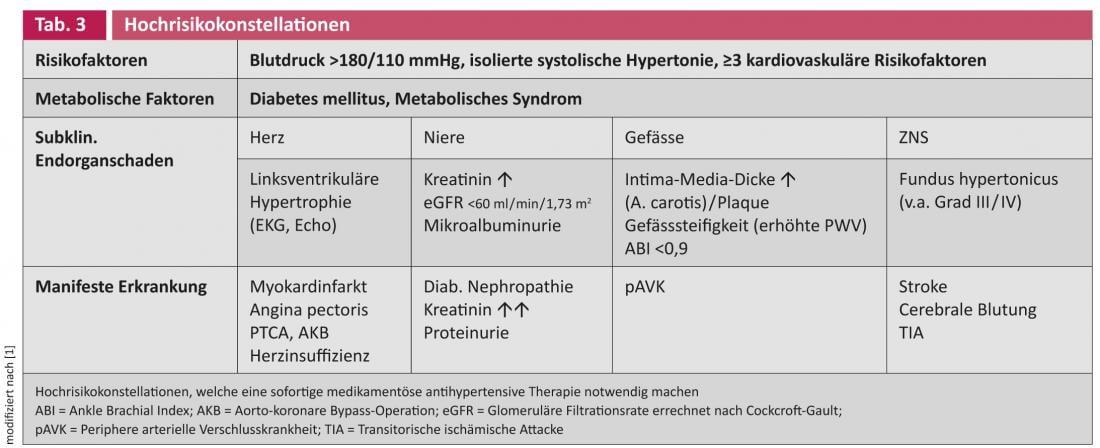

For example, left ventricular hypertrophy, which can be detected relatively easily by ECG or echocardiography, represents both end-organ damage and an independent and potent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [6]. The same applies to the restriction of renal function, which can be estimated very well with the help of creatinine determination, as well as to microalbuminuria, which can be easily and reliably detected in clinical practice [7]. Because of its very good cost-effectiveness, in terms of improved risk stratification and implications for the choice of the most appropriate antihypertensive drug, at least the search for the above-mentioned end-organ damage should be an integral part of the routine work-up of the patient with arterial hypertension. Other constellations that are associated with high to very high cardiovascular risk and can be diagnosed cost-effectively in clinical practice are summarized in Table 3. In addition, of course, other and usually much more expensive methods exist for cardiovascular risk stratification, such as coronary calcium scoring, endothelial function measurements, or MRI for the detection of cerebral lacunae or “white matter lesions.” However, these procedures are currently only recommended for specific questions [1].

UPDATE: Antihypertensive therapy [1].

General Aspects: Furthermore, lifestyle modifications (“LSM”) represent the basis not only for prevention but also for therapy of the patient with arterial hypertension. These lifestyle changes include, for example, restricting daily salt consumption to 5-6 g, controlling body weight, exercising regularly, and not smoking. In patients at low to moderate risk, these measures can be tried for a few months. If there is no success, however, a drug therapy must be initiated quickly.

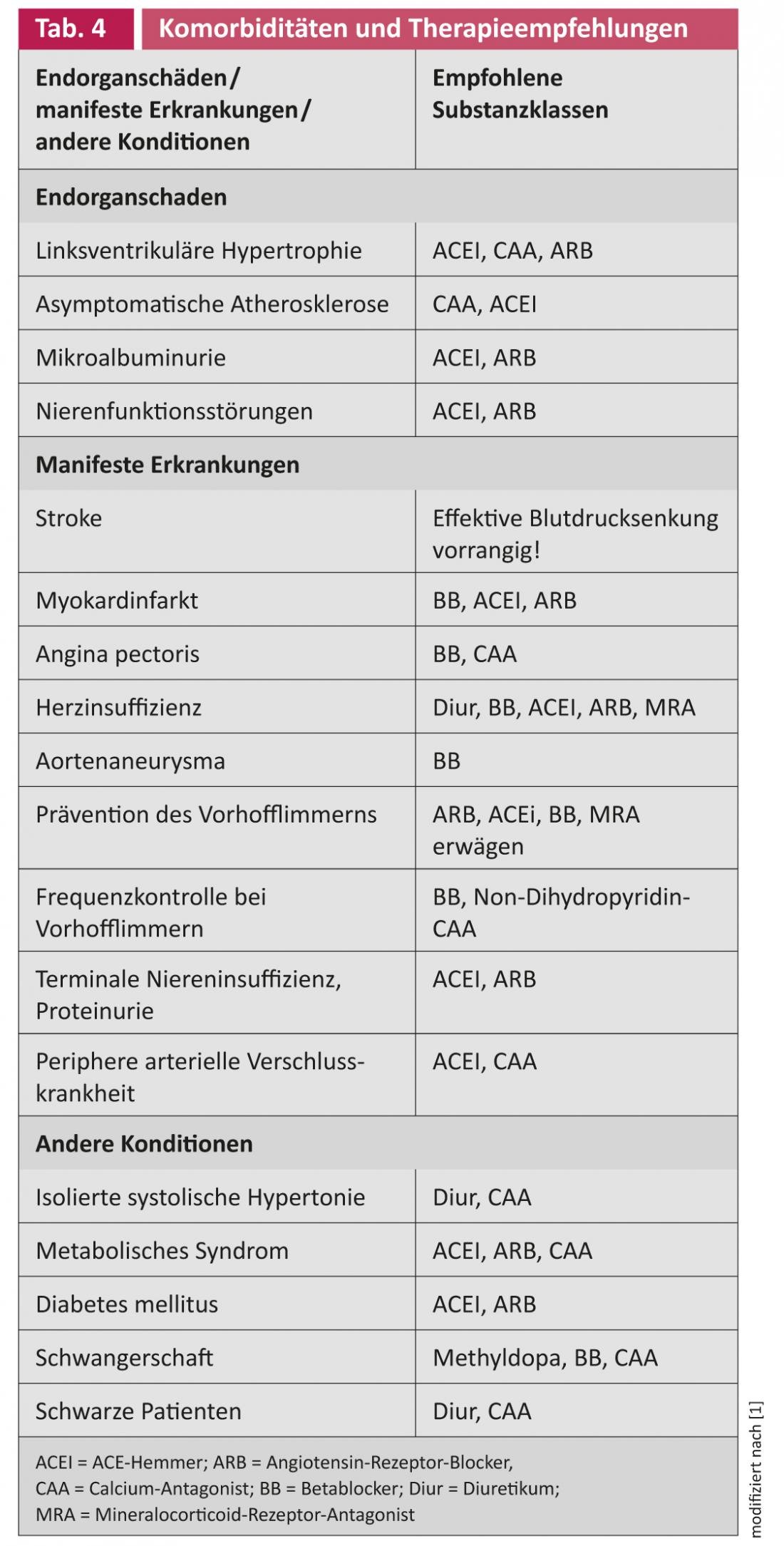

Drug therapy: After various clinical studies and meta-analyses have shown that, with regard to the patient’s prognosis, the reduction in blood pressure itself is primarily decisive, there is no longer a hierarchy of drugs to be preferred (i.e., first-, second-, or third-choice agents) in the new guidelines with regard to initial monotherapy. The major drug classes have similar effects on reducing cardiovascular events; accordingly, ACE inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta blockers (BB), calcium antagonists (CAA), and diuretics (Diur) can be prescribed equally. However, if the patient already has end-organ damage or manifest cardiovascular or renal disease, the choice of drug class should be based on the existing comorbidities (Table 4).

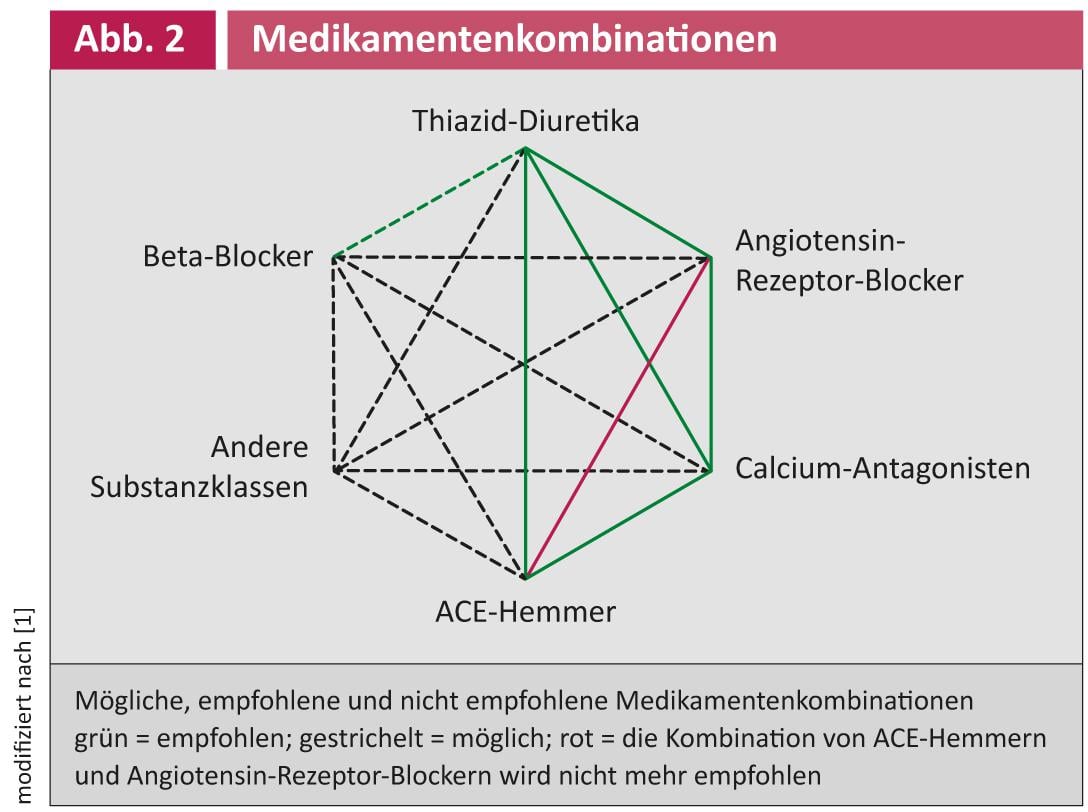

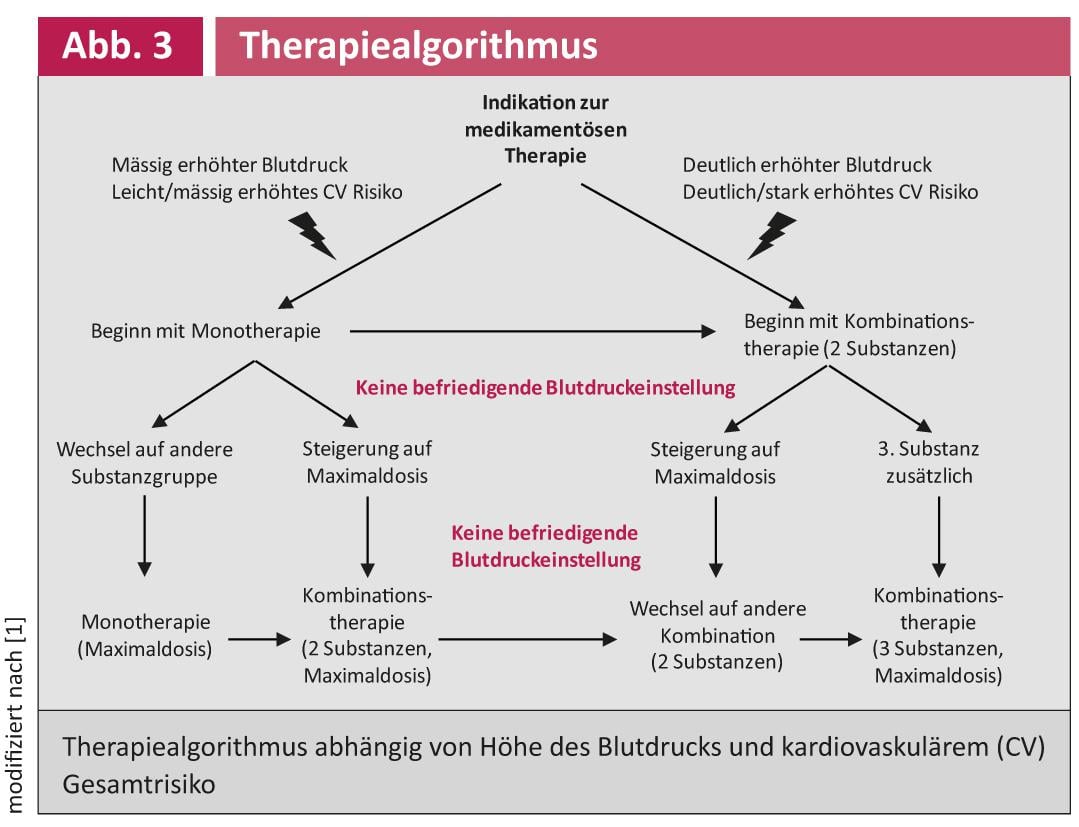

To achieve target blood pressure levels, most patients require more than one medication. The importance of combination therapy was again emphasized in the new guidelines, which is reflected, among other things, in the recommendation to primarily start with combination therapy in cases of high cardiovascular risk or initially significantly elevated blood pressure values. In this context, certain combinations, such as the combination of ACEI with ARB, should be avoided because of a lack of additional benefit with an increased rate of side effects. The currently recommended combinations and the recommended treatment algorithm are summarized in Figures 2 and 3 .

Therapy for High-Normal Blood Pressure? The previous recommendation to start antihypertensive therapy for high to very high cardiovascular risk and high-normal blood pressure values (130-139/85-89 mmHg) was based on rather weak evidence. A re-evaluation of the existing data has now resulted in the new European guidelines no longer recommending therapy in this blood pressure range. However, these patients should continue to be monitored closely.

Therapy in young and old patients with arterial hypertension: In young patients, isolated systolic elevated blood pressure values are not infrequently found. To date, there is no clear evidence that these patients derive significant benefit from antihypertensive therapy, nor that these patients develop manifest arterial hypertension over time. However, these patients should be counseled regarding lifestyle changes and monitored closely.

At the other end of the age spectrum, however, antihypertensive therapy can highly significantly reduce cardiovascular events, especially the incidence of heart failure or stroke. Various studies have shown beneficial effects for Diur, CAA, ACEI, and ARB. Diur and CAA have been shown to be effective in isolated systolic hypertension, which is very commonly found in the elderly [1].

UPDATE: Blood pressure target values

The relevant remeasurements and Changes from previous guidelines include the decision to recommend a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg as a target for (almost) all patients. Previously, 140/90 mmHg was recommended as the target for patients at low and moderate cardiovascular risk, but a blood pressure target of 130/80 mmHg was given for high-risk patients. In people over 80 years of age, a target systolic blood pressure of less than 160 mmHg may be sufficient.

The results of the ACCORD study have contributed significantly to this reassessment [8]. Thereafter, aggressive antihypertensive therapy was not able to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with arterial hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Instead, the number of patients with a decrease in glomerular filtration rate doubled to less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, corresponding to severe renal function impairment.

UPDATE: Therapy-resistant hypertension and new forms of therapy.

Refractory hypertension is defined as a form of hypertension that is not controlled despite lifestyle modifications and therapy with a diur and at least two other antihypertensive agents from other substance classes at adequate doses. Therapy-resistant hypertension can be an expression of lifestyle-associated problems, chronic use of blood pressure-increasing substances, secondary forms of hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, but also an expression of previously undetected end-organ damage – such as renal insufficiency – which leads to high blood pressure. Good antihypertensive effects have been observed in this situation with the use of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA; spironolactone, eplerenone), doxazosin, an increase in diuretic dose, or with the use of loop diuretics [9].

New treatment methods for refractory hypertension – above all renal denervation as the most important innovation in the field of antihypertensive therapy (see article by Dr. Ewen et al., p. 10 ff.) – are currently spreading at a rapid pace. Studies to date show promising results in terms of blood pressure reduction [1, 10]. However, long-term studies on safety and efficacy compared to best available drug therapy are still lacking. In addition, it is not yet known whether the new technical procedures can reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

PD Thomas Dieterle, MD

Literature:

- The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1281-1357.

- Lovibond K, et al: Lancet 2011; 378: 1219-1230.

- Nielsen M, et al: Benefits of implementing the primary care patient-centered medical home: a review of cost and quality results 2012. www.healthtransformation.ohio.gov. Last access: 14/09/2013.

- Fagard RH, et al: J Hypertens 2007; 25: 2193-2198.

- Graham I, et al: Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 2375-2414.

- Bombelli et al: J Hypertens 2009; 27: 2458-2464.

- Ninomiya T, et al: J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 1813-1821.

- The ACCORD Study Group: NEJM 2010; 362: 1575-1585.

- Volpe M, et al: Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2010; 8: 811-820.

- Schmieder R, et al: J Hypertens 2012; 30: 837-841.

CARDIOVASC 2013; no. 5: 4-8.