Sleep disorders are one of the most common complaints in the normal population. Up to a quarter suffer from problems falling asleep or sleeping through the night, or from non-restorative sleep lasting at least six months. Negative consequences are fatigue and drowsiness-related attention and concentration disorders with sometimes fatal consequences in road traffic or in exposed occupational groups. The international classification system (ICSD-2) [1] summarizes a total of 88 sleep/wake disorders. Against this background, rational diagnostics and therapy are essential.

Rational therapy requires accurate diagnosis of sleep-wake disorders. The history should initially divide sleep-wake disorders into two main classes, insomnia with difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep, and hypersomnia in the form of daytime sleepiness and increased sleep duration. Daytime sleepiness refers to a reduced ability to maintain wakefulness and sustained attention. Clinically, sleepiness manifests as a subjective feeling and a tendency to fall asleep, especially in monotonous situations. Sleepiness can be assessed in a standardized manner with questionnaires (e.g., Epworth Sleepiness Score) and objectified and quantified with vigilance tests (Multiple Sleep Latency Test; MSLT and Maintenance of Wakefulness Test; MWT) [2]. Daytime sleepiness should be distinguished from fatigue, which refers to a reduced ability of the entire organism to perform its functions. This concerns motor (musculature) and mental functions in different dimensions (perception, cognition) and psychosocial performance. Clinically, fatigue manifests itself in the subjective feeling of activity-related languor and exhaustion. Increasingly, the Anglo-American term fatigue is also used, which corresponds to a persistent subjectively perceived physical or cognitive state of exhaustion, even without previous stress. Fatigue cannot be objectified or measured, but is scaled in severity using questionnaires (e.g., Fatigue Severity Scale).

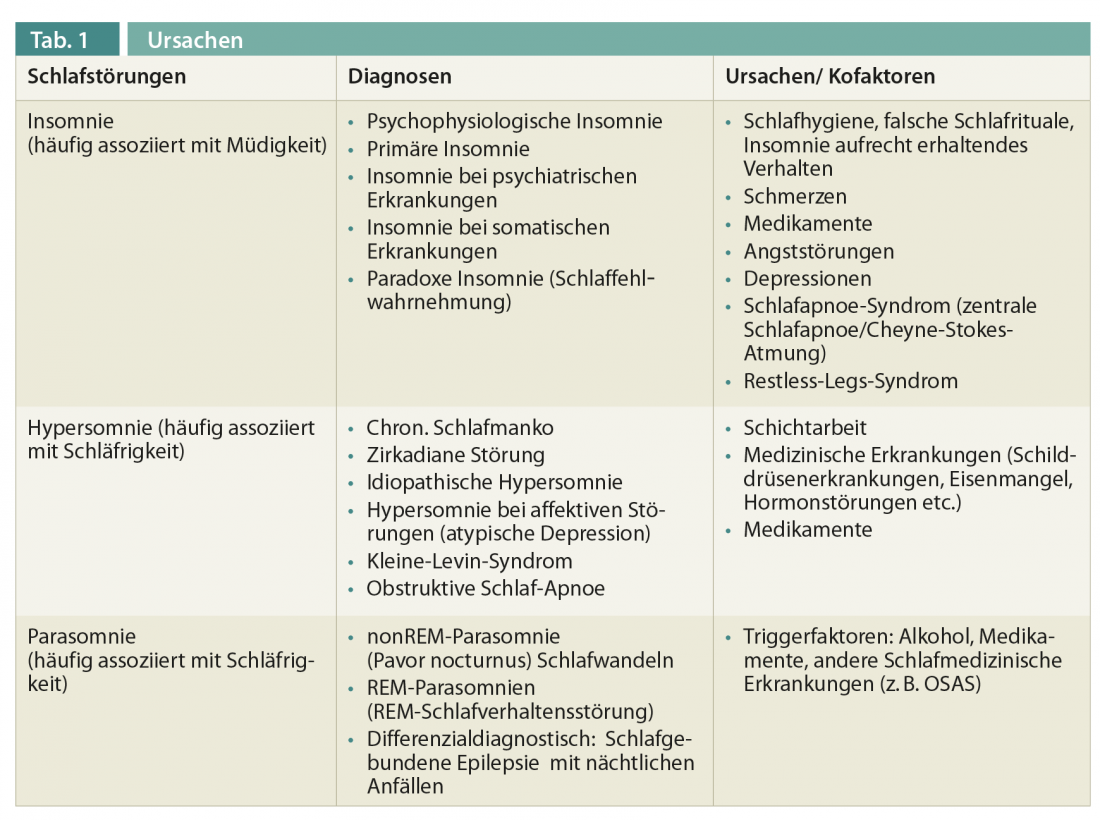

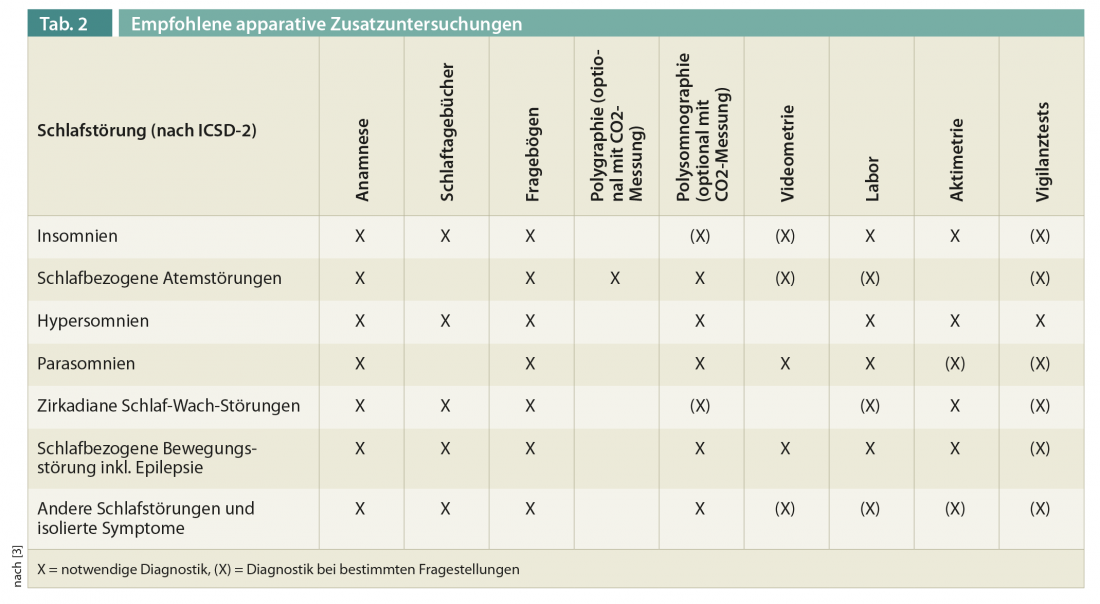

As a third main group, parasomnias should be delineated as inadequate motor, sensory or mental phenomena during sleep, sometimes with complex behavioral patterns. In addition to the three main groups, the ICSD-2 classifies other sleep-wake disorders that cannot necessarily be classified as insomnia, hypersomnia , or parasomnia (e.g., circadian disorders) or that can induce both insomnia or hypersomnia (e.g., sleep-disordered breathing). Extensive additional instrumental and laboratory tests are sometimes necessary for accurate diagnosis. Tables 1 and 2 provide an overview of the most common causes of sleep-wake disorders and the recommended additional apparative examinations. Rational therapy of sleep-wake disorders should be guided by three aspects:

- Which group of sleep-wake disorders is present? (insomnia, hypersomnia, parasomnia, others).

- What is the urgency of the therapy? In addition to medical aspects, occupational health issues and insurance law aspects also play a role here (e.g., can the patient drive a vehicle? Can the patient continue to practice his profession, e.g. pilots).

- What can the non-specialist physician/doctor do and when is a referral to a specialized center necessary?

Insomnia

Most insomnia patients are treated with medication by non-specialist physicians, which often leads to problems in long-term therapy. In addition, the treatment of insomnia has undergone a transformation in recent years. Whereas in the past it was assumed that treatment of the underlying disease (e.g., depression) would simultaneously treat the insomnia sufficiently, today the concept of comorbid insomnia is followed, in which the sleep disorder must also be specifically treated. The basic idea of non-drug therapies involves the identification and treatment of insomnia triggering and maintaining factors [4]. Basic therapeutic rules include providing an adequate sleep environment, establishing evening rituals, avoiding caffeine or alcohol consumption, maintaining a regular sleep/wake rhythm, restricting bedtimes to actual sleep time, leaving the sleep environment if sleep onset or sleep through disturbances occur, and avoiding daytime sleep even after “sleepless nights.” Special psychoeducational sessions play a central role, correcting misinformation (e.g., “I need 8 hours of sleep every day”) and teaching rumination interruption techniques and/or relaxation techniques (progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training) and biofeedback.

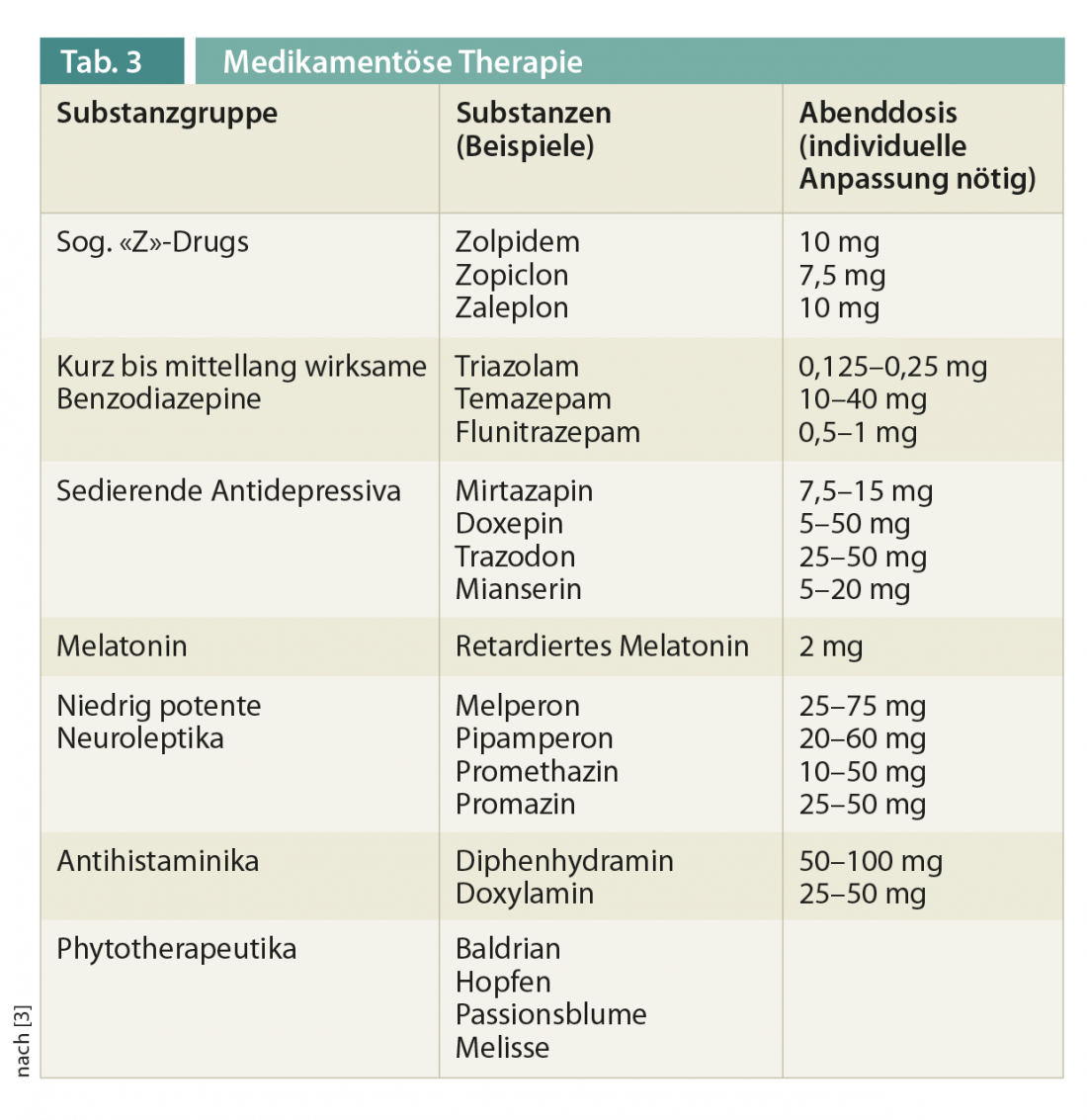

In drug therapy, hypnotics are only permitted for crisis intervention over a period of two to four weeks; general long-term treatment of insomnia cannot be advocated. Table 3 gives an overview of commercially available substances. Individual aspects should be briefly mentioned here. The benzodiazepine receptor agonists are equally effective as the classic benzodiazepines. Interval therapy with benzodiazepine receptor agonists may be a good alternative. The sedating antidepressants trazodone, doxepin, and mirtazapine may be recommended. The low-potency neuroleptics should be avoided in light of substance-specific risks. Melatonin cannot be generally recommended for the treatment of insomnia, with the exception of sustained-release melatonin for the treatment of insomnia in patients with an age >55 years.

Hypersomnias/daytime sleepiness

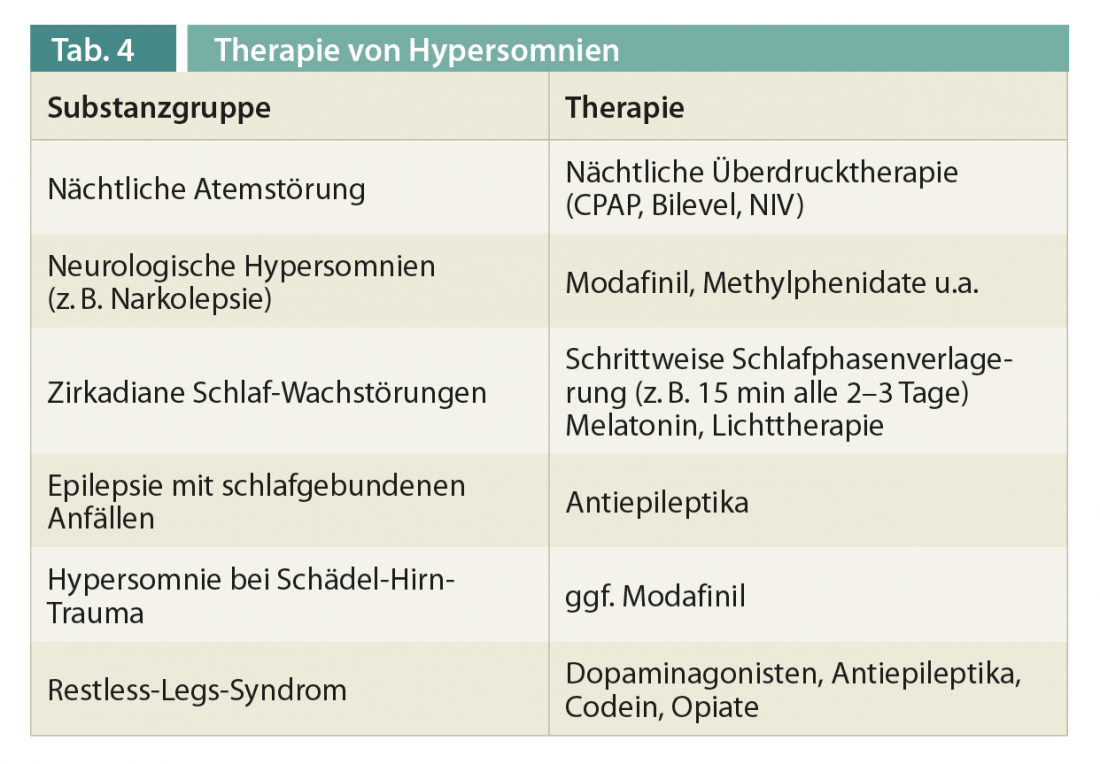

The therapy of hypersomnias depends exclusively on the underlying diagnosis and should be in the hands of a specialized physician. Chronic sleep deficit is one of the leading causes of daytime sleepiness today, and many patients do not know their individual sleep needs. As a rule of thumb, the (actigraphically measured) rest/activity times on workdays and non-workdays should not differ by more than 1.5-2 hours. Circadian disturbances that can lead to daytime sleepiness (or insomnia) should be treated gradually in the form of sleep phase shifting, supported by melatonin and light therapy. Here, careful clarification in the hands of a sleep physician or a chronobiologist is necessary, since the effect of light and melatonin depends on the time of application and the specific syndrome. An overview of therapy for specific hypersomnia/daytime sleepiness is given in Table 4.

Parasomnias

Treatment of parasomnias is aimed at avoiding the triggering factors (alcohol, medications, sleep deprivation, fever, and others) and adjusting the sleep environment (removing objects that are potentially injurious, closing windows). Special nonpharmacologic therapeutic procedures (anticipatory awakening, premedication) should be performed in specialized centers. The evidence on drug treatment is limited to single-case reports with low levels of evidence. Standard therapy consists of benzodiazepines, especially clonazepam or serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although paradoxically these substances can also be triggers for parasomnias. For REM sleep behavior disorder, clonazepam at low doses 0.25-0.5 mg (max. 2 mg) approximately 30 minutes before bedtime is effective in the majority of cases (over 80%). In the case of REM sleep behavior disorder, the patient should also be informed about the increased risk of neurodegenerative disease from the synucleinopathies.

Literature:

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 2nd edn. American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Westchester, Illinois 2005.

- Weess HG, et al, and Vigilance Working Group of the DGSM: Vigilance, tendency to fall asleep, sustained attention, fatigue, sleepiness – diagnostic instruments for measuring fatigue- and sleepiness-related processes and their quality criteria. Somnology 2000; 4: 20-38.

- Non-restorative sleep/sleep disturbances. S3 guidelines German Society for Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine (DGSM). Somnology 2009; 13: 4-160.

- Riemann D, Perlis ML: The treatments of chronic insomnia: A review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies.Sleep Medicine Reviews 2009; 13: 205-214.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2013; 11(1): 28-31.