After the death of a young girl who died of a pulmonary embolism, many are asking: How safe is the pill? The conclusion: the absolute risk is low, the combined pill is best tolerated. However, one should pay attention to contraindications and know when to stop taking the pill immediately.

Two years ago, the case of a young woman occupied the media and doctors: the girl had died of a pulmonary embolism ten months after she had started taking the pill. In Switzerland, 40% of 15- to 34-year-old and 14% of 35- to 49-year-old women use oral contraceptives [1]. A safe contraceptive method, easy to use, which additionally helps some against acne or dysmenorrhea. But after the tragic case of the young girl, many wondered: How safe is the pill? Depending on the preparation, women taking the pill have about a three- to sevenfold higher risk [2, 3] of developing thrombosis. “Because thousands of women take the pill, it is to be expected that some of them will get a thrombosis,” says Jan-Dirk Studt, MD, senior physician and head of the hemostasis laboratory at University Hospital Zurich. “However, young women’s baseline risk for thrombosis is low, so the absolute risk for individuals still remains low.”

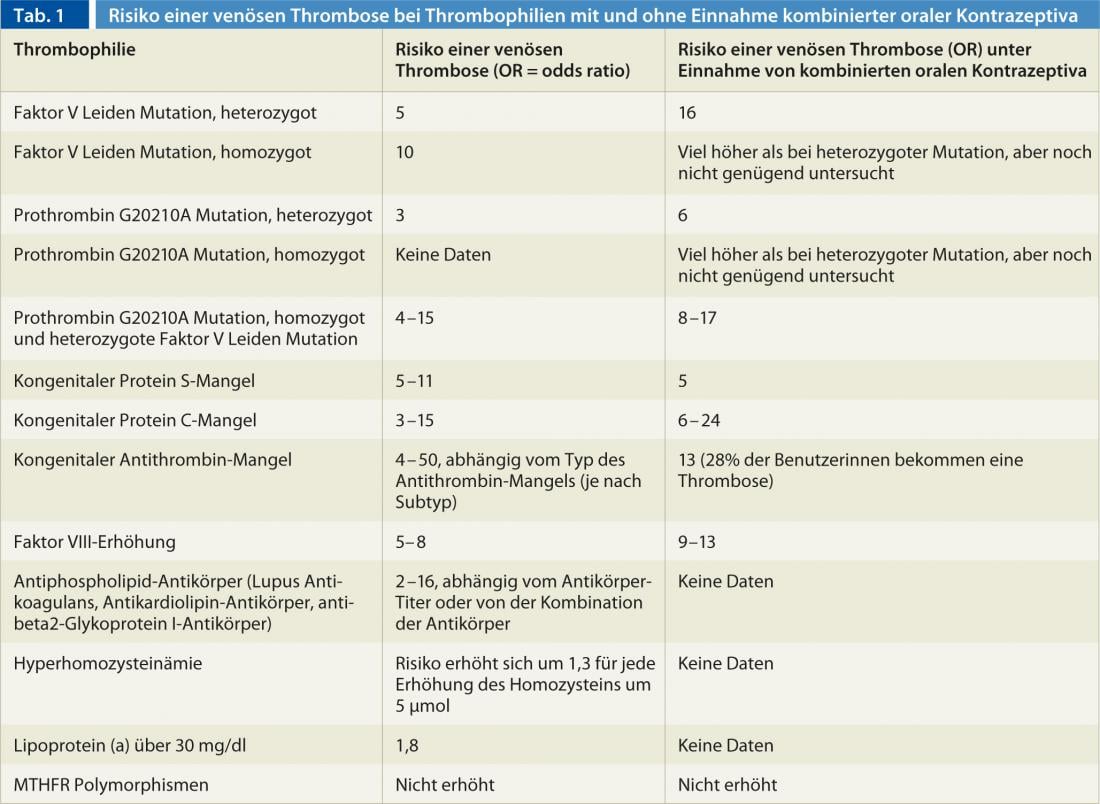

The risk for thromboembolism depends on age, genes, and other risk factors. A common calculation parameter is the so-called woman-years. For example, the risk of thrombosis without the pill is 1-2 per 10,000 woman-years in women aged 15-35, and 3-8 in women aged 35-44. This means that if 10,000 women are observed for one year, one to two or three to eight thromboses will occur. For those on the pill, the risk is about twice as high, so it would be 2-4 or 6-9 thromboses in 10,000 women within a year. Obesity, smoking, varicose veins, immobility due to surgery, injury or travel, and genetic factors can increase the risk of thrombosis severalfold (Table 1).

Risk of thrombosis depends on amount of estrogen

With the pill, the amount of estrogen and the type of progestin determine the risk. “That’s because hormones affect components of the clotting system,” Dr. Studt explains. Thus, ethinyl estradiol promotes clotting by causing procoagulant factors to increase and anticoagulant factors such as protein S to decrease. “Shortly after the introduction of the pill in the 1960s, it became apparent that the risk of thrombosis was largely dependent on the dose of estrogen,” Dr. Studt reports. Over the years, the estrogen dose was reduced more and more, which also reduced the risk of thrombosis. Today’s preparations usually contain 30 µg or 20 µg of ethinyl estradiol. The progestin component appears to counteract the prothrombotic effect of estrogen.

Second generation pills perform best

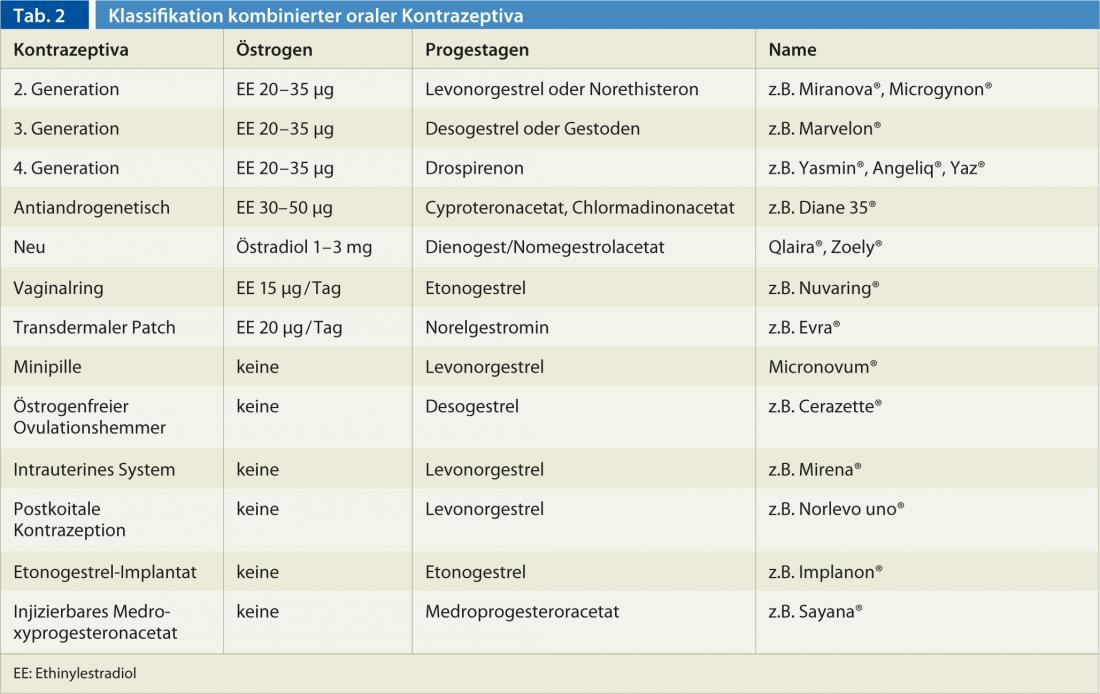

Combined contraceptives containing ethinylestradiol and levonorgestrel belong to the second generation, those containing gestodene or desogestrel to the third, and preparations containing drospirenone to the fourth (table 2). Those containing cyproterone acetate, chlormadinone acetate or dienogest are called antiandrogenic pills. “In addition to the estrogen dose, the progestin component of a pill also affects the risk of thrombosis,” Dr. Studt continues. “Second-generation pills containing the progestin levonorgestrel perform best in this regard.” Thus, second-generation preparations are associated with a fourfold higher risk than if the woman does not take the pill; for gestodene, the risk is about 5.6-fold, for desogestrel 7.3-fold, and for drospirenone 6.3-fold [4]. The antiandrogenic pills, on the other hand, have a fourfold higher than that of the second and thus appear to be the contraceptives with the highest risk of thrombosis [5].

Recently, two new pills without ethinyl estradiol came on the market. One contains estradiol valerate and dienogest (Qlaira®) instead, the other estradiol and nomegestrol (Zoely®). Procoagulant factors are said to be less activated than with second-generation pills, and metabolic parameters such as HDL are said to be less affected [6–8]. Whether fewer thromboses also occur with these pills remains to be seen.

Plasters and ring also increase the risk of thrombosis

Hormone-releasing patches or vaginal rings contain a third-generation progestin component in addition to 20 µg or 15 µg of ethinyl estradiol. The risk of thrombosis does not appear to be lower with this method of application either. Thus, transvaginal and transdermal application also resulted in activation of the coagulation system [9, 10].

Contraceptive methods that work only with progestins, such as the “mini-pill” or the Mirena® intrauterine device, do not activate the coagulation system. Although there are few studies to date that have examined the risk of thrombosis with progestin-only contraceptives, the risk appears to be minimally increased, if at all [11].

“If a girl or young woman wants the pill, I advise the combined pill with estrogen and progestin because it is best tolerated,” says Prof. Michael von Wolff, MD, head of the Department of Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine at Inselspital in Bern. The second-generation pills are the safest in terms of thrombosis risk. “Those of the third or fourth, however, might be more likely to be considered if the patient has certain desires.” For example, pills containing cyproterone or dienogest are more likely to relieve acne. “In no case should you forget to take a detailed medical history to rule out risk factors for thromboembolism and contraindications.” Screening all women for thrombophilia, on the other hand, is not useful, he said. “If there is a family history of thromboembolism, it should be decided on a case-by-case basis.” Dr. Studt advises having the index patient examined first, which is the one in whom the thromboembolism had occurred. “Only if the latter is found to have hereditary thrombophilia should the woman be selectively screened for this thrombophilia.”

Stop taking the pill immediately in case of ACHES

Prof. von Wolff advises against the combined pill only in the case of absolute contraindications. These are migraine with aura, age over 35 and more than 15 cigarettes per day, history of thrombosis, poorly controlled hypertension, migraine without aura in women over 35, and certain liver diseases. “I’m cautious with any marked obesity, large nicotine use, and history of thrombosis in the family – then I advise a progestin pill first.”

The gynecologist has a simple mnemonic for when to stop taking the pill immediately: For ACHES: Abdominal pain (liver problems), Chest pain (pulmonary embolism, heart problems), Headache (migraine), Eye (vision problems, cerebral circulation, migraine), Swelling (thrombosis). At the same time, however, Prof. von Wolff warns against exaggerated caution: “Discussions about the thrombosis risk of the pill are good and important, but this is exaggerated.” It should not be forgotten that pregnancy also carries an increased risk of thrombosis and that pregnancy itself is a risk for young girls. “If you choose the pill carefully, it is a reliable contraceptive, especially for young girls, and very safe in absolute terms,” says Prof. von Wollff. “The benefits outweigh the minimal risks in most cases.”

Literature/Sources:

- Hess T: Checklist Hormonal Contraception. Ars Medici 2011, 64-67.

- Van Hylckama Vlieg A, Middeldorp S: Hormone therapies and venous thromboembolism: where are we now? J Thromb Haemost 2011; 9: 257-266.

- Rott H: Thrombotic Risks of oral contraceptives. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2012; 24: 235-240.

- van Hylckama Vlieg A, et al: The venous thrombotic risk of oral contraceptives, effects of estrogen dose and progestogen type: results of the MEGA-case control study. BMJ 2009; 339: b2921.

- Klipping C, et al: Hemostatic effects of a novel estradiol-based oral contraceptive: an open-label, randomized, crossover study of estradiol valerate/dienogest versus ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel. Drugs 2011; 11:159-170.

- Junge W, et al: Metabolic and haemostatic effects of estradiol valerate/dienogest, a novel oral contraceptive: a randomized, open-label, single-center study. Clin Drug Investig 2011; 31: 573-584;

- Agren UM, et al: Effects of a monophasic & combined oral contraceptive containing nomegestrol acetate and 17b- oestradiol compared with one containing levonorgestrel and ethinylestradiol on haemostasis, lipids and carbohydrate metabolism. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2011; 16: 444-457.

- Gaussem P, et al: Haemostatic effects of a new combined oral contraceptive, nomegestrol acetate/17b-estradiol, compared with those of levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol. A double-blind, randomised study. Thromb Haemost 2011; 105: 560-567.

- Sitruk-Ware R, et al: Effects of oral and transvaginal ethinyl estradiol on hemostatic factors and hepatic proteins in a randomized, crossover study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92: 2074-2079.

- Jick SS, et al: Risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using a contraceptive transdermal patch and oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception 2006; 73: 223-228.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Venous thromboembolism and hormonal contraception. Guideline No. 40. London: RCoG 2004; 13; World Health Organization. Cardiovascular disease and use of oral and injectable progestogen-only contraceptives and combined injectable contraceptives. Contraception 1998; 57: 315-324.

FAMILY DOCTOR PRACTICE