Sport is popular as never before and, if practiced with moderation, is very healthy. Whereas in the past it was mainly younger people who played sports, today it is almost normal to run into 70-year-old joggers. With the increase in awareness of health, the number of seniors participating in sports is increasing. The question of why it is athletes over the age of 35 who dominate ultramarathons is now also occupying researchers. The following article discusses the findings to date and provides an overview of the physiological changes that occur with age.

A generally valid definition of the term senior athlete does not exist. Various scientific authors and international sports federations include people aged 35 and over for most sports . The Swiss “Swiss Master Athletics” sets the threshold for the definition of senior athletes already at 30. This somewhat arbitrary definition is based on the scientific knowledge that top performance in a wide range of sports declines after the age of 35, i.e. the sporting zenith has been passed. However, it is this observation that has generated a lively discussion in recent years as to where the causes of the decline in performance of these so-called senior athletes lie.

Formula for the calculation of heart rate

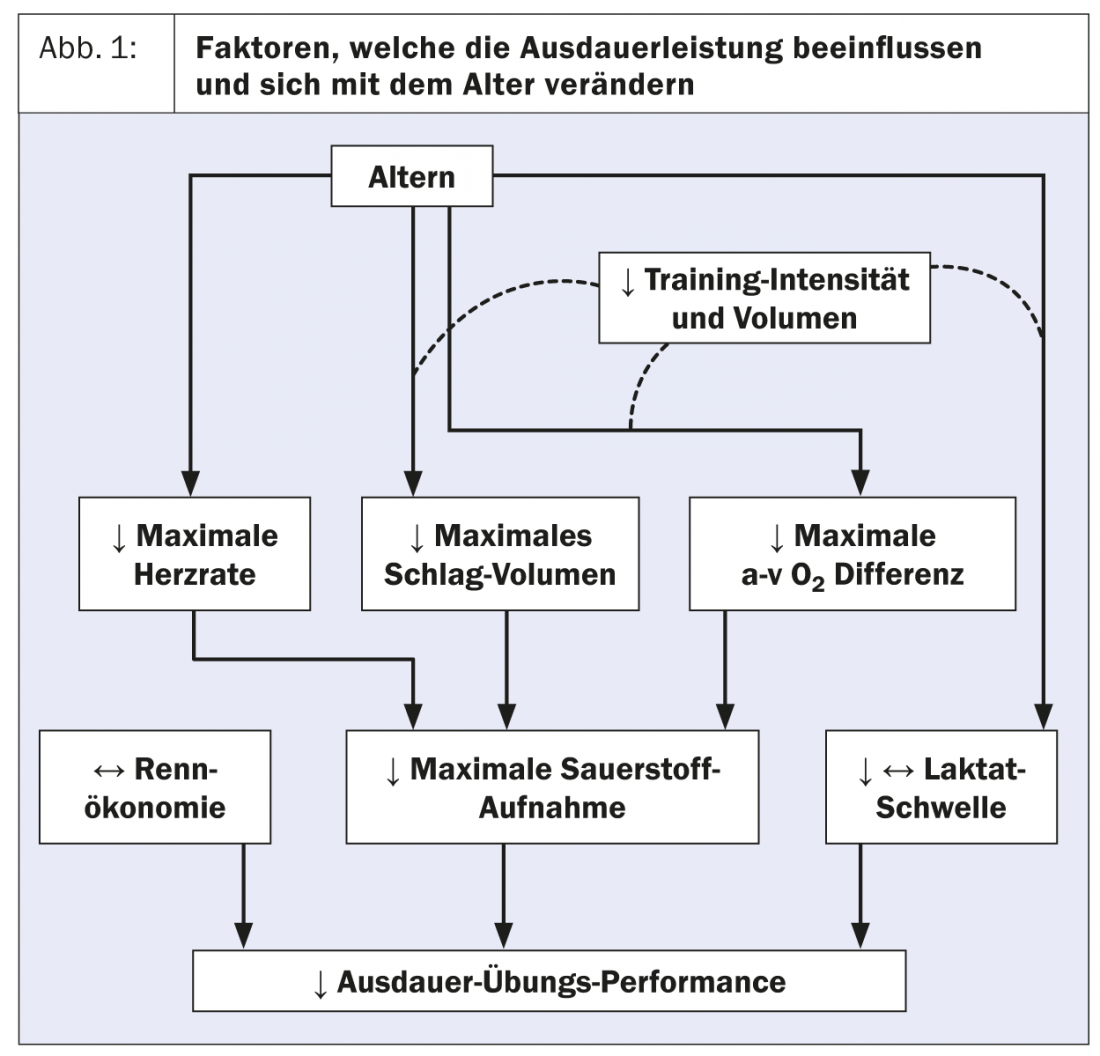

The maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) decreases continuously from the age of 35. VO2max is a direct measure of the global power of a heart as an oxygen pump as well as the ability of the relevant body muscles to take up oxygen. Endurance athletes are thus increasingly lacking the essential component for developing strength, since aerobic energy cannot be produced without oxygen.

One of the main factors influencing VO2max is maximum cardiac output (HMVmax), which in turn depends on maximum heart rate (HRmax) and stroke volume (SVmax).

HRmax can be estimated by a simple calculation for each age (200-age[Jahren] = HRmax). It decreases continuously with age. However, the highly simplified formula was repeatedly described as inaccurate, and alternative formulas were proposed. The sole influence of age on maximum heart rate seemed to eclipse important other influencing factors, so gender, physical activity, and body mass index were examined.

However, even in large meta-analyses such as the HUNT Fitness Study, age alone was shown to have a significant effect on HRmax. The current formula of this study is HFmax = 211 – 0.64 × age.

Can seniors counteract the decline?

So now the HFmax decreases with age. Senior athletes would need to raise their SVmax to achieve the same HMVmax as younger athletes. The SV is a measure of the maximum force of the heart and thus of the heart muscle. However, because with age the heart muscle increasingly loses elasticity and parts of the muscle are replaced by connective tissue, SV increase with age is not expected. The arterial vessels, which, as downstream organs of the heart, on the one hand pass on and on the other hand even reinforce the performance of the heart (the function of the large arteries as a wind chamber), also lose their capacity with increasing age. Accordingly, senior athletes cannot achieve the same maximum performance.

However, HMVmax is not the only factor influencing performance. The anthropometry of a person also changes with advancing age, for example, the percentage body muscle mass decreases and the fat mass increases in the opposite direction. While extra muscle is an active performance-enhancing factor, extra body fat is just ballast.

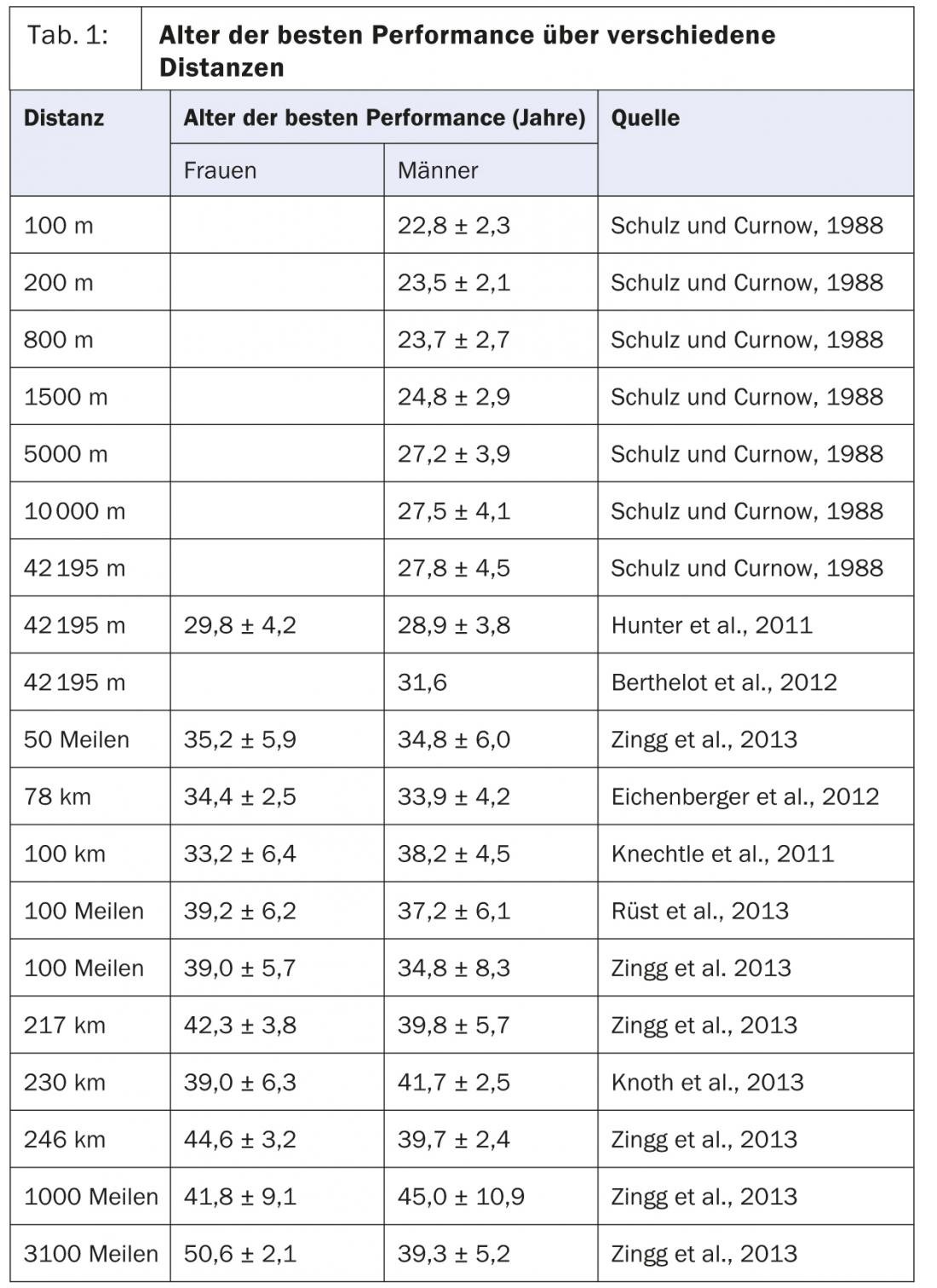

Table 1 shows the age of best performance over different distances, collected from different studies.

Seniors do sports

Why, despite all these age deficits (Fig. 1) , have reports of outstanding performances by older athletes increased in recent years? A well-known and specifically noteworthy example is Ed Whitlock, the only 70+ year old runner to date to ever run a marathon under 3 hrs. Such extreme examples are frequently publicized, but the phenomenon of older elite athletes is little known in the broader community as a whole. In running, senior athletes are regularly among the best ultramarathon runners. An ultramarathon is defined with a running distance that exceeds the classic 42.195 km distance. Compared to the normal marathon, it is less frequent and has a much less widespread press. The ultramarathons have become much more popular, with some events reaching starting fields of several hundred or even a few thousand people. The phenomenon that runners over the age of 30 are already the dominant age group in normal marathons intensifies as the distance or duration of a race increases.

The age of peak performance

Senior runners make up the majority of successful participants in ultramarathons. On average, a 100-km runner is 45 years old. While early and mid-twenties dominate the short (up to 400 m), middle (up to 1500 m) and long-distance distances (10,000 m), the marathon elite is already mostly much older with an average age of almost 30 years. This so-called “age of peak performance” (ADSL) continues to rise beyond the marathon distance. Thus, both sexes show an average ADSL of about 35 years already from 80 km, which interestingly just corresponds to the scientific definition of the senior athlete. The oldest ADSL was collected from the nearly 5000 km self-transcendence of New York at about 50 years. Since there are no longer official runs so far, the question about an upper limit of the ADSL cannot be answered.

Reasons for the success of senior athletes

Why do so many seniors seem to be overcoming their physiological or anthropometric deficits? While the aforementioned deficits of late thirties still seem insignificant, the question of why mid-forties dominate runs beyond the 200-km mark is much more difficult to answer.

The majority of researchers seek explanations in the fact that senior athletes who have been trained to the maximum throughout their lives hardly lose any of their performance capacity. The age-related decline in VO2max of untrained individuals is reported to be approximately 1% per year of age after age 35. This loss can be significantly reduced by regular training, so that top athletes lose only about 0.5% per year.

Other studies investigated muscle mass loss resp. Fat mass gain with age. This showed a clear difference between non-athletes and athletes. For example, senior athletes lose significantly less muscle mass and gain less fat mass with age than non-athletes. This raises the suspicion that these anthropometric changes are due to underuse of the musculature rather than pure age increase.

Race economy

Senior athletes thus forfeit less of their physiological and anthropometric prerequisites. Still, this doesn’t explain why they win ultramarathons. Is it because of the experience? But what should be understood by experience in running? Is this the perfect planning of a race, the race economy regarding the division of forces or perhaps pure psychology in the sense of motivation, colloquially called “fighting spirit”? While the former is difficult and therefore hard to quantify, it has been suggested that senior athletes may travel more economically. Race economy is defined as the energy required to maintain a constant speed in the submaximal range and is calculated from the oxygen consumed per unit time. Especially in long and ultra long distance races this has a great relevance, because the runners are always in the submaximal range. This explains why even a certain loss of maximum performance can still be sufficient to keep up with the fastest. A study by Quinn et al. were even able to show that race economy has no influence on power loss with increasing age [1]. Since senior athletes showed comparable race economy to young elite runners, this cannot be cited as a decisive advantage of senior athletes either. Especially in ultramarathons, race economy seems to be more strongly associated with performance than the VO2max discussed.

Psychological influences

Psychological influencing factors have hardly been investigated so far. Since the “fighting spirit” is a hardly quantifiable quantity, the few works published to date on the subject of motivation and ultramarathons have mainly focused on the goals pursued by ultra runners. Ultra runners were found to be more intrinsically motivated and fact-based. Whether and how large a possible psychological advantage of senior athletes is needs to be evaluated in future studies.

The factors discussed thus far appear to provide little benefit to senior athletes. For this reason, non-personal factors were sought and an economic reason was supposedly found: While marathon running has developed into a million-dollar business in recent years and sometimes yields large starting fees and bonuses for top runners, ultra-marathon runners are, with few exceptions, unpaid amateurs. This could provide an explanation as to why the most competitive runners are not involved with ultramarathons, but with runs up to and including the classic marathon distance.

Future areas of research

Ultimately, we cannot answer the question of why senior athletes dominate ultramarathons. While great strides have been made in recent years in the knowledge of physiology and anthropometry, potential psychological causes still lag behind. Future studies are needed to scientifically quantify the benefits of seniors.

Conclusion for practice

- Physiologically, the performance peak is exceeded at around 35 years of age. Nevertheless, senior athletes (>35 years) dominate ultramarathons.

- As the distance and/or duration of an ultramarathon increases, the age of peak performance increases.

- Lifelong endurance exercise reduces the age-related decrease in maximum oxygen uptake by about 50%.

PD Beat Knechtle, MD

Matthias Alexander Zingg, MD

Christoph Alexander Rüst, MD

Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Rosemann

Prof. Dr. Romuald Lepers

Literature:

- Quinn TJ, et al: Aging and factors related to running economy. J Strength Cond Res 2011 Nov; 25(11): 2971-9. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318212dd0e.

- www.pponline.co.uk/encyc/vo2-max-can-veteran-athletes-prevent-a-decline-in-aerobic-capacity-281.

- Saunders PU, et al: Factors affecting running economy in trained distance runners. Sports Med 2004; 34(7): 465-85.

- Tanaka H, Seals DR: Endurance exercise performance in Masters athletes: age-associated changes and underlying physiological mechanisms. J Pysiol 2008 Jan 1; 586(1): 55-63. Epub 2007 Aug 23.

- Knechtle B: Ultramarathon runners: nature or nurture? Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2012 Dec; 7(4): 310-2.

- Tanaka H, et al: Age-predicted maximal heart rate revisited. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001 Jan; 37(1): 153-6.

- Nes BM, et al: Age-predicted maximal heart rate in healthy subjects: The HUNT Fitness Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2012 Feb 29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01445.x. [Epub ahead of print]

- Shibata S, Levine BD: Biological aortic age derived from the arterial pressure waveform. J Appl Physiol 2011 Apr; 110(4): 981-7. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01261.2010. Epub 2011 Feb 3.

- Knechtle B, et al: Personal best marathon performance is associated with performance in a 24-h run and not anthropometry or training volume. Br J Sports Med 2009 Oct; 43(11): 836-9. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.045716. epub 2008 Apr 2.

- Wroblewski AP, et al:. Chronic exercise preserves lean muscle mass in masters athletes. Phys Sportsmed 2011 Sep; 39(3): 172-8. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.09.1933.

- Trappe SW, et al: Aging among elite distance runners: a 22-yr longitudinal study. J Appl Physiol 1996 Jan; 80(1): 285-90.

- Fournier PE : Elite senior athletes. Physiological modifications related to performance decrease in elderly. Rev Med Suisse 2012 Sep 26; 8(355): 1838-40.

- Wroblewski AP, et al: Chronic exercise preserves lean muscle mass in masters athletes. Phys Sportsmed 2011 Sep; 39(3): 172-8. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.09.1933.

- 14. Krouse RZ, et al: Motivation, goal orientation, coaching, and training habits of women ultrarunners. J Strength Cond Res 2011 Oct; 25(10): 2835-42. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318204caa0.

- 15. Eichenberger E, et al: Age and sex interactions in mountain ultramarathon running – the Swiss Alpine Marathon. Open Access J Sports Med. 2012;3:73-80.

- Hunter SK, et al: Is there a sex difference in the age of elite marathon runners? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011, 43: 656-664.

- Knechtle B, et al: Age-related changes in 100-km ultra-marathon running performance. Age Dordr 2012 Aug; 34(4): 1033-45. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9290-9. epub 2011 Jul 28.

- Knoth C, et al: Participation and performance trends in multistage ultramarathons – the “Marathon des Sables” 2003- 2012. Extreme Physiology & Medicine 2012; 1: 13.

- Rüst CA, et al: Analysis of performance and age of the fastest 100-miles ultra-marathoners worldwide CLINICS, in press Impact factor: 2.05 (2013).

- Schulz R, Curnow C: Peak performance and age among superathletes: track and field, swimming, baseball, tennis, and golf. J Gerontol 1988; 43(5): 113-120.

- Zingg M, et al: Analysis of participation and performance in athletes by age group in ultra-marathons of more than 200 km in length. International Journal of General Medicine 2013; 6: 209-220.

- Zingg MA, et al: Runners in their forties dominate ultra-marathons from 50 to 3,100 miles. CLINICS (Sao Paolo), in press.

- Korhonen MT, et al: Age-related differences in 100-m sprint performance in male and female master runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003 Aug; 35(8): 1419-28.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 11(10), 16-19