Wound care was one of the first therapeutic measures ever used and developed by humans. Especially in the last 50 years, there has been a complete paradigm shift as far as the use of wound dressings is concerned.

The model of wound healing lies in nature. Probably since the beginning of mankind, it has been observed that trees and plants secrete sap or resins when they are injured. These juices agglutinate the defect and quite obviously lead to the healing of the injury. Thus, today it is believed that this inspiration about nature gave rise to the first wound dressings made of leaves, resins and barks.

Wound care was one of the first therapeutic measures ever used and developed by humans. Especially in the last 50 years, there has been a complete paradigm shift as far as the use of wound dressings is concerned.

Wound treatment at that time

One of the first literary references to the treatment of wounds is the papyrus of Edwin Smith, which dates back to 1900 BC. In it, there are detailed descriptions and instructions for the care of acute injuries: “Now that you have sewn up his wound, you shall put fresh [Fleisch] on it the first day. You must not connect them. Anchor the patient to his or her anchorage (by which is likely meant maintaining the patient’s usual lifestyle) until the wound heals. You have to treat it daily with lard, honey and sharpie.”

As dressing material fine linen is mentioned in the writings as it was used e.g. also by the mummy makers. Another testimony of the ancient bandaging technique is the image on a clay bowl of Achilles bandaging his friend Patroclus in 500 BC.

A few centuries later, Claudius Galen (129-210 AD), a Roman physician and philosopher of Greek origin, dealt intensively with the subject of “wound healing”. He also described the classic signs of inflammation that are still used today: Rubor (redness), Tumor (swelling), Calor (warmth), Dolor (pain), Functio laesa (functional restriction). One of the main concerns of his scientific work was the theoretical foundation and systematization of medical knowledge.

The first three books dealing exclusively with the treatment of wounds were written by Paracelsus (1493 to 1541 AD) and were first published in 1563. They are entitled “Drei Bücher Von wunden und schäden, sampt allen jren zufellen, und derselben vollkommener Cur, Des Hochgelarten unnd weitberhümpten Aureoli Theophrasti Paracelsi von Hohenheim” (Three Books on Wounds and Damages, together with All Their Accidents, and the Perfect Curation of the Same) and describe in great detail on 152 pages the observations that Paracelsus made on the “living object” during the healing process of injuries. Here, too, we find statements that are still valid today, such as “The healing of wounds and injuries happens according to certain laws. Nature does not follow you, but you must follow it”.

In the course of the following centuries, wound care methods became more and more sophisticated and differentiated. Linen, hemp, wool and cotton were used as dressing materials. In 19th century Germany, two books were long considered the standard works in the field of wound treatment: “Gründlicher Bericht von den Bandagen”, written by Heinrich Bass around 1720 and “Kurze praktische Verbandlehre” by Joachim Friedrich Henckel from 1849.

The discovery of wound cleansing with antiseptic fluids by Joseph Lister (1827-1912) also occurred during this period. By chance, he discovered the bactericidal effect of carbolic acid in 1864. A major danger for the patient, namely the infection of his wound by bacteria, could thus be limited. It was not until years later that the many side effects caused by carbolic were recognized and described. However, the absolute necessity of treating infected wounds antiseptically has remained paramount to this day.

However, it was still not known how wound healing really takes place. All recommendations and theories were derived from the observations and conclusions of the researching physicians, but there was no evidence or even measurement results for them yet.

Wound treatment today

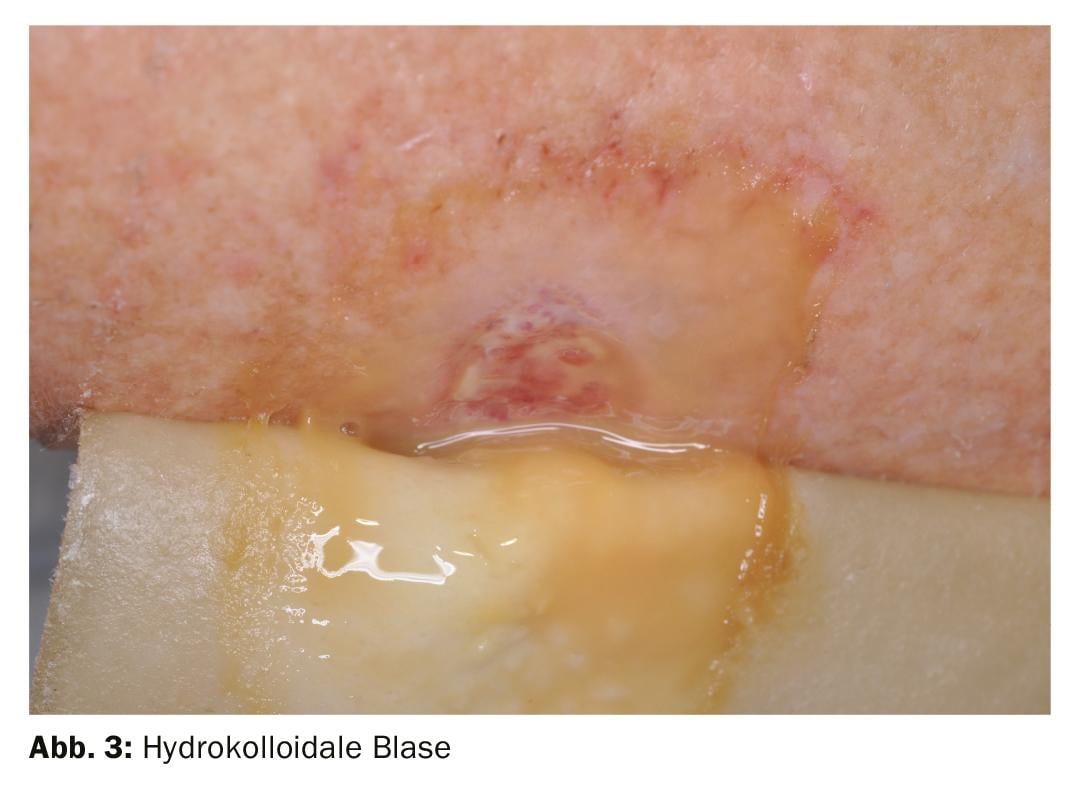

The story of modern wound care today begins in 1962. George D. Winter discovered in experiments on pigs that new tissue formation can take place up to 50% faster in a moist wound environment, closed to external influences, than under dry crust, scabs or dry dressings. [1] The natural model for his research was the blister, which is formed by friction (e.g. when hiking) and which heals according to exactly the same principle. The previously prevailing opinion that a wound must be treated dry and preferably in the air so that it can breathe has been refuted.

He was able to determine that a moist wound environment provides an optimal climate for the many substances that promote wound healing. The importance of the substances contained in the wound exudate was discovered!

In 1963, another clinical study also proved that not only does the moist environment contribute significantly to faster healing, but that a constant temperature (approximately 35 to 37°C) is also essential for optimal healing conditions. [2] The temperature should be maintained for as long a time as possible (several days). In this context, the term “wound rest” has become established.

These groundbreaking findings led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of acute and chronic wounds. Many researchers of various scientific orientations discovered the topic for themselves and, based on Winter’s findings, tried to further investigate the process of wound healing.

Acute and chronic wounds

An acute wound (Fig. 1) is damage to the skin that occurs in intact tissue (e.g., abrasion). The cause or trigger of the damage is known and the healing procedure follows a clearly described scheme. An acute injury is usually healed after 21 days [3].

The chronic wound (Fig. 2) results from a more or less long previous disease that leads to tissue damage or prevents new tissue from forming. [4] A wound is described as chronic if it does not show any healing tendency even after 3 months [5].

When selecting a wound dressing, it does not matter whether the wound is acute or chronic. Only the prioritization changes: In the case of an acute injury, the wound-healing effect occurs immediately after application. In the case of the chronic wound, the cause of the healing disorder must first be clarified and, if possible, eliminated before a wound dressing can develop its full effect.

Before applying a wound dressing: wound cleansing

A central component of the treatment of acute as well as chronic wounds is the targeted wound cleansing of the wound surface, the wound margin and the skin surrounding the wound. The aim of wound cleansing is to remove coatings, foreign material and microorganisms from the wound as completely and as atraumatically as possible by physical measures and/or antibacterial treatment of the wound. There are several ways to do this:

Clean

Sterile gauze or fleece swabs are suitable for wound cleansing, which are moved vigorously over the wound bed in circular movements, either moist or dry. For an effective result, it is necessary to apply this method of procedure several times.

Sinks

In both acute and chronic wounds, irrigation of undermining and ducts is of great importance. The density of germs in a wound can be reduced many times over by extensive rinsing with an antibacterial wound irrigation solution. Conventional syringes with attached button cannula or catheters can be used for this purpose.

Wet-dry phase

The wet-dry phase is a special form of wound cleansing. In contrast to cleaning or rinsing, the wet-dry phase involves the wound margin and the wound environment.

The procedure is carried out in 2 steps: For the wet phase, multilayer compresses are soaked with a neutral solution or a wound antiseptic and applied to the wound and the skin surrounding the wound. The duration of the wet phase is between 10 to 20 minutes and depends on the carrier solution used and the condition of the wound bed.

For the drying phase, multi-layer compresses are again applied, but this time dry. It usually lasts 10 minutes and is used to absorb excess moisture, cell debris and adhesive residues from the stratum corneum.

Debridement

Stubborn coatings of necrosis or fibrin cannot be removed from the wound by the methods already described. Here, “bed-side” debridement has established itself as a fast, effective and inexpensive measure. Use a sharp spoon, a ring curette or a scalpel for this purpose. If pain occurs, the wound area can be treated in advance with a local anesthetic.

Whether acute or chronic, only a clean wound can heal.

Modern wound dressings

With Winter’s discovery, the industry sensed potential for modern wound therapeutics. In 1967, the first hydrocolloid dressing was launched on the market: Varihesive®. This dressing used the knowledge of moist wound treatment and mimicked the bladder given by nature. You can also compare the effect with a greenhouse, which creates an optimal climate for the plants. Active ingredients are not necessary for this.

Arriving in the 21st century, we have an almost unmanageable number of modern dressings that guarantee moist wound healing, regulate exudate flow and can remain on the wound for several days.

Requirements for a modern wound dressing

In order to be able to optimally implement the experience gained in the last 50 years in daily practice, modern wound dressings should meet certain requirements.

The most important role is played by the warm, moist environment. The climate under the wound dressing should not be too dry, but also not too wet. To regulate this, the absorption and retention capacity of the dressing must be precisely matched to the local conditions (Fig. 3). Most manufacturers provide information on this in the package insert.

Another point is the water vapor permeability (MVTR). As described above, a dressing does not need to be able to maintain oxygen circulation to the outside. But the water vapor released by the skin must be able to diffuse through the dressing in sufficient form. Otherwise, maceration of the wound bed and surrounding skin will occur.

In addition, a modern wound dressing should protect the wound from external influences (all around 360°), provide mechanical protection and ensure temperature regulation in the wound area.

Selection of the appropriate wound dressing

The selection of the appropriate wound dressing depends on the exudate flow of the wound and its location on the body. Wounds that exude heavily should be covered with a pad that can absorb enough fluid for several days.

An important part of selecting an appropriate wound dressing is an accurate assessment of the dressing that has been removed. It provides information on the amount of exudate, the color, the odor and the absorption and retention properties of the product used (Fig. 4). A close look before disposal in the waste garbage can is always worthwhile.

Today, wound dressings are divided into substance groups, similar to drugs. Products that are mainly used for the treatment of chronic wounds include:

Wound filler

One issue that must be included in the decision-making process is wound depth. Since the effect on the healing process can only take place if the wound dressing is applied directly to the wound bed, so-called wound fillers must be used for deep wounds (>3 mm). Here are the most important product groups: [6]

Alginates

Alginates consist of fibers of brown algae and can absorb about 20 times their own weight in exudate. They can be conveniently tamponaded into a wound cavity and promote autolysis of the wound due to their high calcium content. In addition, they can be used to stop bleeding.

Hydrofibers

Hydrofibers consist of carboxymethylcellulose, can also absorb approx. 20 times their own weight in exudate and have the positive property that, in contrast to an alginate, they have an exclusively vertical absorption capacity. This prevents maceration of the wound edges.

Hydrogels

Gels consist mainly of an amorphous mass, up to 96% of which is water. They are used for wounds that do not promote enough exudate to create a moist environment. Sometimes they are also used to rehydrate coatings such as fibrin or necrosis.

Special case: the medicinal honey

Honey has long been known as a remedy. Hippocrates and Paracelsus used honey in many of their prescriptions.

Important supplier for healing purposes is the New Zealand Manuka honey. In order for the natural product to become medicinal honey, it receives treatment with gamma rays. This results in a medical product with approval for wound treatment. Manuka honey contains methylglyoxal (MGO) as an essential ingredient.

According to current medical law, no “normal” honey (not even organic products) may be used for wound care. Food and dietary supplements are not allowed by law to be used for medical purposes.

Medicinal honey is available as a gel, honey alginate or honey plate.

Wound covers

So-called wound dressings are used for superficial wounds or for closure when using wound fillers. These are the most important product groups:

Hydrocolloids

Hydrocolloid is the oldest “modern” wound dressing. Hydrocolloids contain strongly swelling particles embedded in a carrier substance of synthetic rubbers. Following the example of the blister, the wound exudate is converted into a gel-like mass by the ingredients used, so that the wound remains moist (Fig. 5). Hydrocolloids are no longer used so often today because they can increasingly be replaced by more modern products such as foams.

Foams

Nowadays, a variety of different foam dressings are available. They consist of either hydropolymers or polyurethane. They have good absorption and retention properties, especially when equipped with an additional layer of polyacrylate. Cellular components and wound exudate are absorbed into the structure of the foam and stored. A foam dressing protects the fresh tissue from traumatic effects and secondary infections from the outside without impeding gas exchange.

Slides

Medical films consist of a polyurethane backing layer coated with a hypoallergenic polyacrylate adhesive. Films are ultra-thin, transparent and highly permeable to water vapor. Since they cannot absorb wound exudate, they are mostly used to fix wound dressings. Taped with a foil, each wound dressing becomes waterproof and the patient can go showering with it.

Conclusion

Choosing the right wound dressing can be helpful in many ways: The wound heals faster, more painlessly and there is a more beautiful scar result afterwards. Plus, the right dressing in the right place at the right time helps save money.

Nevertheless, the best dressing is of no use if the cause of a wound healing disorder is not clarified and diagnosed.

Literature:

- Winter George D: Formation of the Scab and the Rate of Epithelization of Superficial Wounds in the Skin of the Young Domestic Pig. Nature volume 1962; 193: 293-294.

- Winter George D: Effect of Air Drying and Dressings on the Surface of a Wound. Nature volume 1963; 197: 91-92.

- Lippert H: Wound Atlas. MVH Medical Publishers 2001.

- Münter C: Advances in modern wound care. Uni-Med-Verlag Bremen 2005.

- Dissemond J, et al: pH of the environment of chronic wounds, Dermatologist 2004; 54: 959-956.

- Wound Material Compendium Switzerland, Medinform 2019; www.wundmaterialkompendium.ch

Further reading:

- Panfil EM: Caring for people with chronic wounds. Verlag Hans Huber Zurich, 3rd edition 2015.

- DNQP: Expertenstandard Pflege von Menschen mit Chronischen Wunden, Verlag Hochschule Osnabrück, 2nd edition 2015; www.dnqp.de

- DGfW: S3 guideline on local therapy of chronic wounds in patients with the risks peripheral arterial occlusive disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic venous insufficiency, 2012; www.dgfw.de

- SAfW: Wound Compendium of the Swiss Society for Wound Treatment, mhp Verlag Wiesbaden 2012; www.safw.ch

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(10): 6-11