Schizophrenia is a common mental illness with alteration of perception of thinking and self-experience. It has a major impact on the daily life of those affected and can severely limit their quality of life and functionality. Psychopharmacological treatment of negative symptoms is a key factor in the success of therapy and is essential for improving the patient’s quality of life.

With a lifetime prevalence of 0.5-1.6%, schizophrenia is not a rare disorder in the general population worldwide. The probability of developing schizophrenia at some point in life is even higher if there is a family history of the disease. If a parent or sibling has the disease, the prevalence may be as high as 5-10% [1].

Schizophrenia is associated with impaired functioning, as well as loss of years of life and quality of life. In addition, this chronic condition causes increased healthcare utilization. The average cost in Switzerland in 2012 was EUR 39,408 per patient. Of these costs, 64% were for lost production, 24% were for direct medical costs, and 12% were for family care [2].

However, with well-controlled therapy to manage symptoms while minimizing side effects, good medication adherence can be achieved, which in turn is associated with INCREASED patient functionality and reduced healthcare resource use [14].

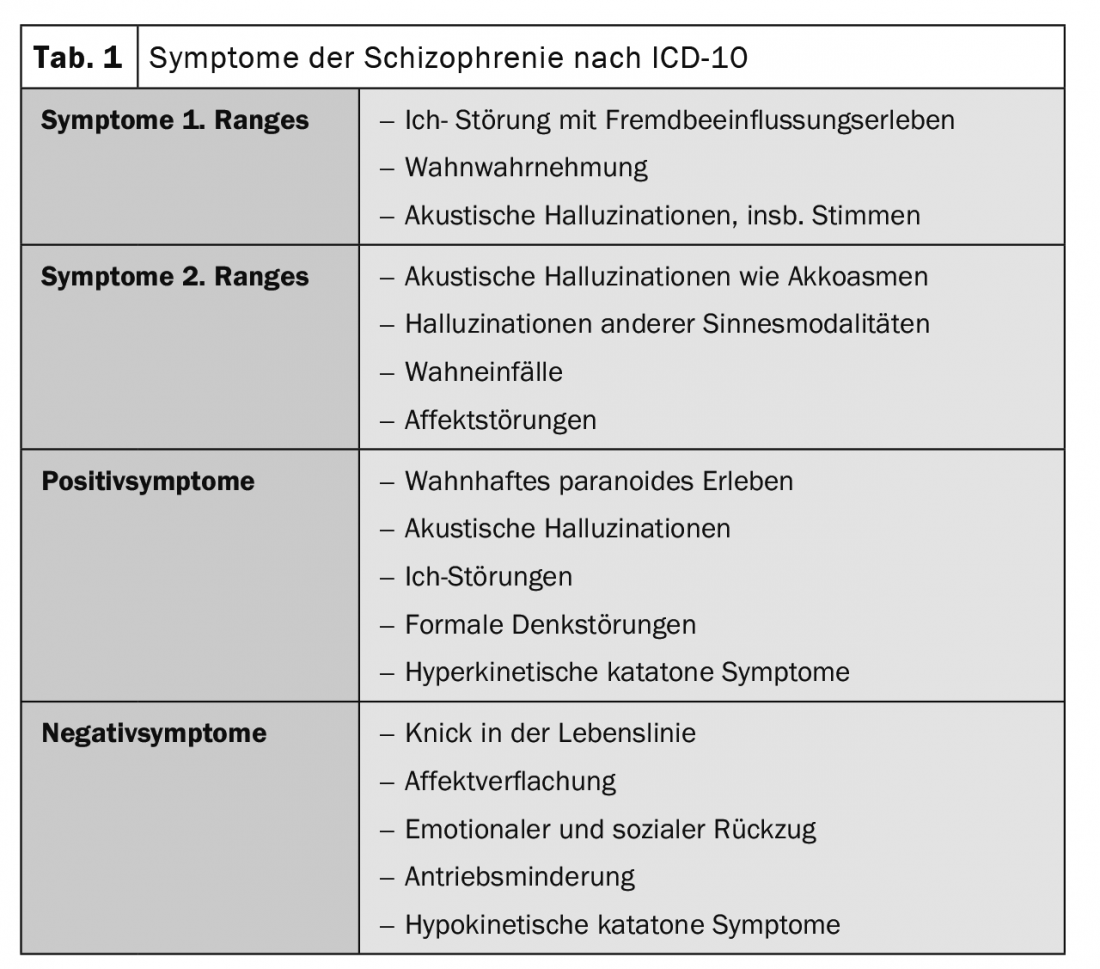

Distinguishing schizophrenia from acute polymorphic psychosis is essential in terms of prognosis. Here, by definition, the time course of the disease is decisive. According to the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria, at least one of the first-order symptoms or two second-order symptoms must be present continuously for at least one month (Table 1). Acute polymorphic psychosis represents a significantly lower restriction for the functionality of patients in their everyday life compared to schizophrenia [2].

It is clear that in terms of the bio-psycho-social approach to therapy, psychotherapy is an extremely important component of therapy, but this article will focus primarily on drug therapy.

In the initial acute setting, psychopharmacologically, D2 blockade is crucial to treat positive symptoms. Positive symptoms, which are more dramatically impressive and often the cause of a patient attracting the attention of medical professionals and police, have been the main target of treatment. However, modern research is increasingly concerned with long-term effects of the drugs and the functionality of patients back in their daily lives. Whether patients with schizophrenia can live independently, maintain stable social relationships, or return to work is clearly determined by the degree of negative symptoms. These reflect the loss of normal functions and feelings, such as loss of interest and inability to feel pleasure [3].

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the effects of atypical antipsychotics and to address patients’ negative symptoms and quality of life.

Physiology of the dopamine system

The neurotransmitter dopamine plays an important role in the cerebrum, diencephalon as well as in the brainstem. Four pathways are relevant in the context for schizophrenia. They include the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, the mesocortical dopamine pathway, the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway, and the tuberoinfundibular dopamine pathway [3,4].

Mesolimbic: The mesolimbic dopamine pathway projects from the ventral tegmental area of the midbrain to the nucleus accumbens, a part of the limbic system. This area is involved in many behaviors, thinking and perception. From pleasurable sensations to the euphoria of drug abuse, this area is heavily involved. Also, here the positive symptomatology such as delusions and hallucinations in psychosis seems to be caused by hyperactivity of these pathways. This overactivation of D2 receptors is considered the main target of antipsychotics against the positive symptoms of schizophrenia [3,4].

However, because stimulation of D2 receptors in the mesolimbic pathway also leads to the experience of pleasure, blocking these receptors may not only reduce positive symptoms but also block reward mechanisms. This deprives patients of motivation, interest, and pleasure in social interactions, leaving them apathetic and anhedonic [3,4].

Mesocortical: Also originating in the ventral tegmental area of the midbrain, the mesocortical dopamine pathway sends its axons to the prefrontal cortex. In the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the mesocortical dopamine pathway is sometimes responsible for cognitive symptoms. Decreased dopamine concentration in this brain area leads to impaired attention, information processing, or serial learning, among other things. Executive functions such as priority setting and goal setting or behavioral modulation based on social cues may then be further impaired. Further blockade of D2 receptors in this area by typical antipsychotics may lead to worsening of negative symptoms.

In contrast, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex appears to be the origin of the affective symptoms of schizophrenia [3,4].

Nigrostriatal: In the brainstem, dopamine sometimes performs an important function in the control of motor function. The dopaminergic fibers of the nuclear area substantia nigra project to the striatum, where they have an inhibitory effect on the motor impulses of the cerebrum. Thus, the substantia nigra performs an essential function of movement initiation and influences extrapyrimidal motor function and muscle tone.

In untreated schizophrenia, this pathway is not affected. However, if the D2 receptors are blocked by the administration of antipsychotics, motor side effects may result, which are grouped under the term extrapyramidal symptoms [3,4].

Tuberoinfundibular: The fourth dopamine pathway of interest to us is the tuberoinfundibular dopamine pathway. This projects from the hypothalamus to the anterior pituitary and controls prolactin secretion. Blocking dopamine increases prolactin levels, which can cause side effects such as galactorrhea or amenorrhea [3,4].

Regulation in the vomiting center: Furthermore, dopamine has regulatory functions in the formatio reticularis, where it has an activating effect on the area postrema, the vomiting center, and thus triggers nausea and vomiting [3,4].

Physiology serotonin

In the case of atypical antipsychotics, in addition to D2 binding, the additional effect at serotonin receptors is crucial for their function. The binding of clozapine for example, is significantly stronger towards the 5HT2A receptor than to the D2 receptor. Thus, in addition to providing adequate antipsychotic effects, clozapine causes significantly lower EPS, as 5HT2A antagonization in turn leads to dopamine release in the striatum. More specifically, serotonin is released in the cerebral cortex, binds to 5HT2A receptors on glutamatergic pyramidal neurons, and thus activates them. Activation of these neurons in turn leads to glutamate release in the brainstem, which stimulates GABA release. GABA then binds to dopaminergic neurons projecting from the substantia nigra to the striatum, inhibiting dopamine release. When 5HT2A receptors are blocked, this effect is eliminated and dopamine neurons are disinhibited, reducing side effects. With atypicals such as risperidone or paliperideone, as well as aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine, 5HT2A binding is much weaker in comparison, but these also exert a partial agonistic effect on 5HT1A receptors. 5HT1A receptor stimulation in the cortex also stimulates downstream dopamine release in the striatum [3,4].

Negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients.

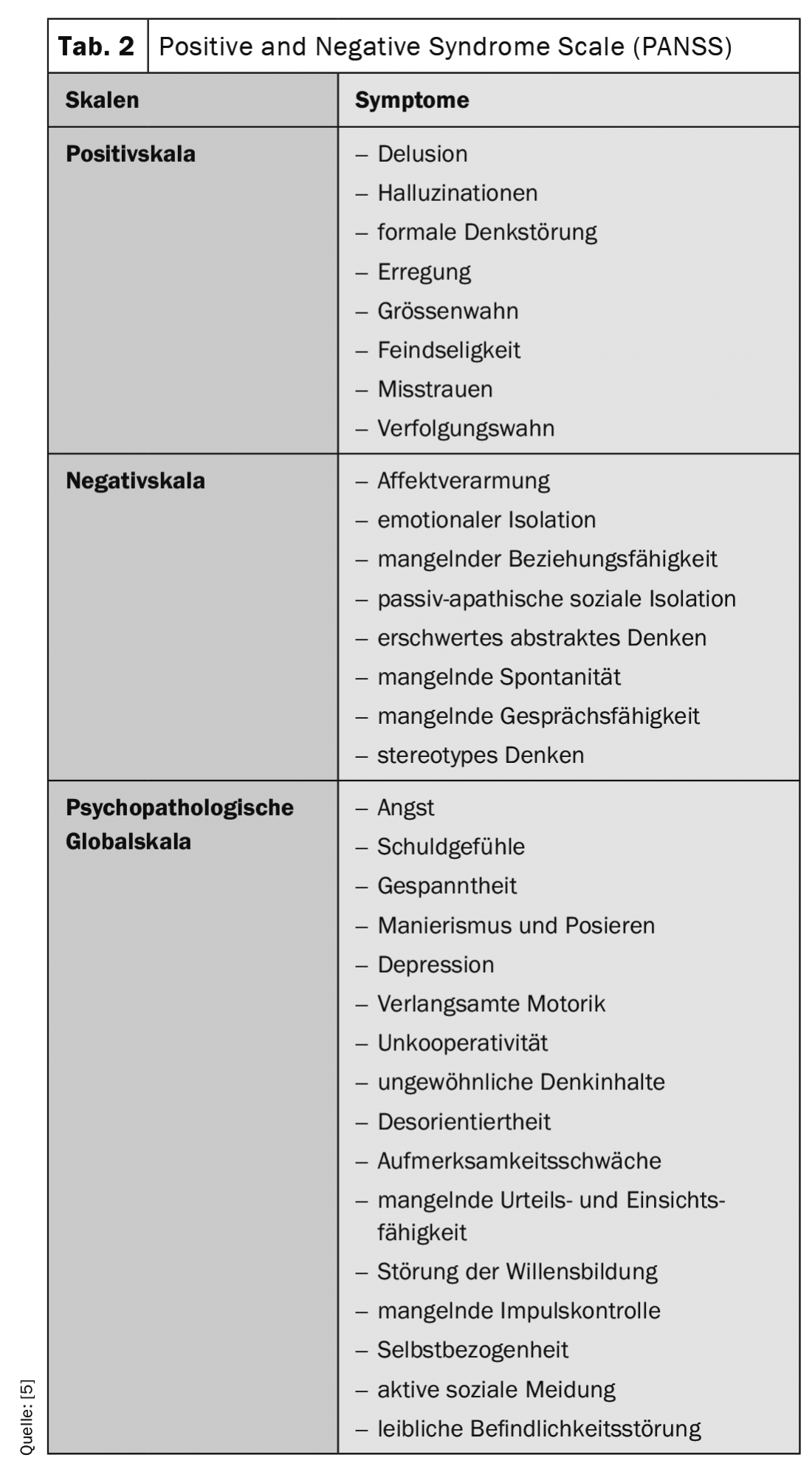

As a further development of the Psychopathology Rating Schedule (Singh and Kay 1975), Kay et al. 1987, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Table 2). The PANSS consists of a formalized psychiatric interview lasting approximately 45 minutes. In the interview, 30 symptoms are scaled. There are levels from 1 to 7, with seven being the most pronounced symptomatology. Symptoms are assigned to three scales: the positive scale, the negative scale, and the psychopathological global scale. This assessment is based on the individual’s condition over the past week. Information obtained through staff or family members is also considered in the assessment. Information on daily behavior is a great help in detecting emotional withdrawal, passive-apathetic social isolation, affect lability, active social avoidance, hostility, unwillingness to cooperate, agitation, and slowed motor function. During the interview, direct observations of the patient’s affective, cognitive, and psychomotor functions, as well as receptive and interaction skills, are possible [5].

Assessment of functionality and well-being in schizophrenia patients.

In recent years, in addition to the objectifiable disease and health indicators, the patient’s individual experience, well-being and functionality in everyday life have increasingly become the focus of therapy goals. Patient well-being and quality of life are now important endpoints in drug trials [6–8].

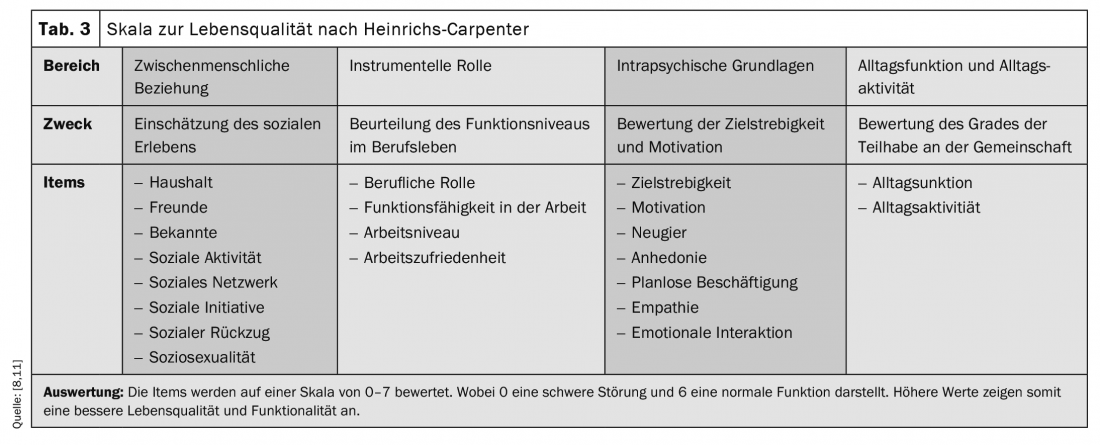

Until now, the main focus has been on the reduction of positive symptoms and long-term stabilization with extrapyrimidal symptoms kept as low as possible. However, in order to capture the whole symptom picture of schizophrenia, the semi-structured questionnaire with 21 items by Heinrichs & Carpenter was published for the first time in 1984 (Tab. 3) . This questionnaire sometimes includes negative symptoms and has become a standard instrument for assessing the quality of life of schizophrenic patients [9]. Since then, new questionnaires have been continuously developed, such as the WHO generic questionnaire [10].

Psychopharmacological treatment options and adherence.

Thanks to second-generation antipsychotics, it is now also possible to influence symptoms such as neurocognition, negative and affective symptoms, as well as functional level and quality of life [6,12]. Whereas, according to cross-sectional and long-term studies, a higher quality of life in turn contributes to better patient adherence in the long term and to func-tio-neal remission [13].

In general, it is important to avoid pronounced blockade of the D2 receptor. According to the S3 guidelines for schizophrenia, there is evidence for amisulpride and olanzapine. In addition, meta-analyses show clozapine as the drug with the greatest effect sizes on negative symptoms but also with the highest rates of side effects. A recently published study was able to show the superiority of cariprazine compared to risperdone for negative symptoms [14].

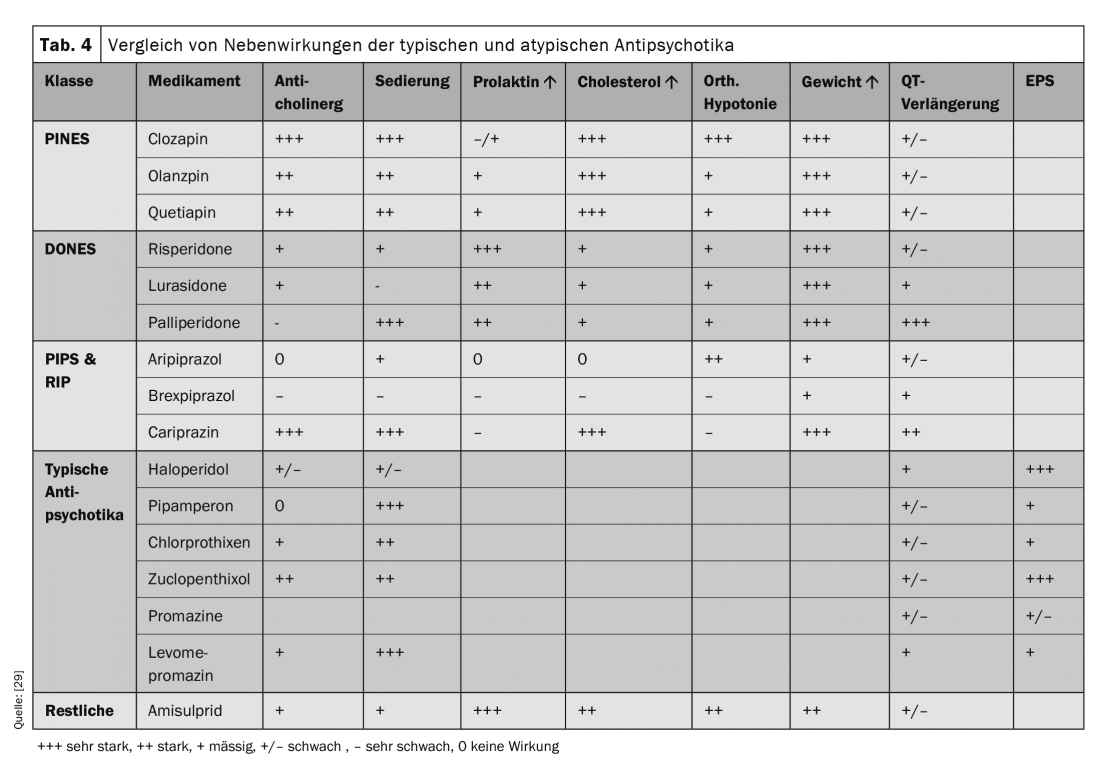

Discontinuation rates due to side effects are higher for classic antipsychotic medications than for second-generation antipsychotics [15]. The most commonly reported side effects that were at least moderately bothersome included difficulty thinking and concentrating (32.2%), restlessness and nervousness (28.2%), insomnia (28.4%), weight gain (25.8%), drowsiness (25.1%), and sedation (16.0%). Most of these side effects are significantly associated with decreased likelihood of drug adherence. EPS and agitation reduce adherence probability by 43% and metabolic side effects by 36%. Aside from side effects, patients who were younger, more highly educated, and not employed were less likely to be adherent [16].

Patients with full adherence are significantly less likely to be hospitalized for a mental health reason, hospitalized for a nonmental health reason, or visit the emergency department for a mental health reason [14].

In summary, side effects of antipsychotic medications are common and significantly associated with lower adherence, which is associated with increased healthcare resource use [16]. In addition, side effects also bring a significant reduction in life expectancy. In particular, metabolic side effects such as weight gain, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, alteration of sugar metabolism to diabetes. Currently, second-generation antipsychotics are prescribed about 95% of the time in the United States. However, the risk of metabolic syndrome (extreme abdominal fat, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension) is greater than with typical antipsychotics. Several antipsychotics in both classes can lead to QTc prolongation and ultimately increase the risk of fatal arrhythmias. These medications include haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. The metabolic side effects are especially important to consider with the so-called PINES. Not to be forgotten with clozapine is the risk of agranulocytosis, which is the most dangerous side effect and can occur in about 1% of patients [16,17].

The metabolic side effects of atypicals include weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, as mentioned earlier. Before starting therapy, patients should be screened for risk factors. Family history should also be taken in detail, focusing on weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose levels, and lipid status. Patients clearly at risk should be treated with ziprasidone or aripiprazole if possible. Patients should have regular monitoring of weight, BMI, and fasting blood glucose [16,17].

The topic of personalized medicine is also very important in psychiatry. The goal is to find the right treatment for the right patient and is based on the widely held assumption that patients vary significantly in their response to treatments. Even with antipsychotic medications, the response of patients with psychosis is considered to vary widely among individuals [18].

In the recent meta-analysis by Winkelbeiner et al. However, no evidence was found that antipsychotic medications had an increased variance in responses compared with the placebo group. This indicated that there was no personal element of response to treatment. As noted in this study, it cannot be completely ruled out that subgroups of patients respond differently to treatment, but it suggests that the average treatment effect for the individual patient is a reasonable assumption [18].

Likewise, it must be pointed out that long-term treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications again appears to cause an increased tendency to relapse. This knowledge is based on the results of short-term weaning studies. Patients would relapse in 25-55% within the first 6-10 months after discontinuation. However, this relapse rate is higher the longer the antipsychotic therapy has already lasted [19–22].

It is possible that this discontinuation paradox can be attributed to the drug-induced buildup of an excess of dopamine receptors before discontinuation or to the prior buildup of hypersensitive dopamine receptors. However, the exact relationship of long-term medication and recidivism rate is still under discussion [20,22,23].

Treatment of depressive symptoms

An essential component of improving patients’ functionality and well-being is co-treatment of depressive symptomatology such as social withdrawal, listlessness, and depressed mood.

Depressive symptomatology must be distinguished from negative symptomatology in schizophrenia. Fifty to 80% of schizophrenic patients develop at least one negative symptom and about 30% experience persistent negative symptoms. Negative symptoms are a typical characteristic in schizophrenia and are less pronounced in other psychotic disorders. They influence the subjective quality of life and also the long-term course of patients. Negative symptoms include: reduced expression (flattening of affect, alogia) and apathy (asociality, anhedonia) with impairment of goal-directed activities. Negative symptoms lead to high levels of distress and affect quality of life, relationships, work life, and social functioning. Furthermore, this also increases the rehospitalization rate.

Differentiating negative symptomatology from depressive symptomatology can be challenging and requires clinical experience. Common to depressive symptomatology and negative symptomatology are: reduced drive and interest, and reduced expression. For pure depressive symptomatology, depressed mood, depressive cognitions (guilt, hopelessness, self-evaluation), and other symptoms such as decreased appetite, early morning awakening, and morning low are typical. Suicidality occurs more frequently with depressive symptoms [20, 22-24].

There is a long history of treating depressive symptoms with antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics, which have fewer adverse drug effects than classical antipsychotics, have been used as monotherapy or augmentation with antidepressants to treat depression with as well as without psychotic symptoms [25].

The antidepressant effect of typical antipsychotics is probably related to inhibition from DA2/DA3 receptors of the dopamine system in the prefrontal cortex. This increases the dopamine concentration there. The antidepressant effect of atypical antipsychotics includes rapid unlocking of dopamine receptors, reduced activation of dopamine and 5HT1A receptors, inhibition of 5-HT2A/2C receptors, inhibition of alfa-2 receptors, blockade of norepinephrine transporters (NET), regulation of the glutamate or GABA systems, decreases in cortisol, and increases in brainderived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is a growth factor found in the body in various tissues, such as the forebrain, hippocampus and cerebral cortex, where it strongly influences long-term memory and the increase in synaptic connections.

Thus, the effect of atypical antipsychotics on mood is related to the rapid release of dopamine from the receptor and the consequent consistent decrease in dopamine receptor activation.

SSRIs increase transmission from the 5HT in the telencephalon and nucleus ceruleus and thus decrease discharge from norepinephrine receptors. The atypical antipsychotics increase norepinephrine receptor unloading by inhibiting 5HT2A, α-2, or norepinephrine transporters. This may be why second-generation antipsychotics are effective against depressive symptoms in patients with limited benefit from SSRIs [25].

Several studies confirmed that glutamate (GA) plays a key role in the neurobiology and therapy of depressive symptomatology. Glutamate is one of the main neurotransmitters in the CNS. Physiological functions are mostly implemented through mechanisms such as via the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA). The NMDA receptors belong to the glutamate receptors and are mainly found in the hippocampus and cerebrum. They play a significant role in the formation of memory via long-term potentiation in the brain, as well as in other interactions. An abnormally functioning glutamate system was found in patients with depressive symptomatology, and drugs with GA-like mechanism of action showed improvement in depressive symptomatology. Several metabolic GA receptors (AMDA, AMPA) and the GA transporters are associated with symptomatic treatment [25].

In many patients suffering from schizophrenia, the depressive symptoms and the pressure of suffering go so far that they increasingly think about suicide. Approximately 50% of schizophrenia patients attempt suicide during the course of their illness [26].

In a study comparing the effects of clozapine and olanzapine on suicidality, clozapine was shown to be superior to olanzapine in favorably affecting suicidality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychosis. Patients hospitalized or referred for crisis intervention with an indication for drug therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, and sedatives were also significantly less frequent on clozapine [26,27].

Comparison of effects of different drugs in negative symptoms.

A recently published systematic review compared the effects of 32 antipsychotics (Table 4) . In the overall reduction of symptoms, as well as in the individual categories of reduction of positive and negative symptoms, clozapine was clearly in the lead. With few exceptions, only clozapine, amisulpride, olanzapine, and risperidone were significantly more effective than other antipsychotics [27].

In patients with predominant negative symptoms, amisulpride was the only antipsychotic to show significant improvement in symptoms compared with placebo, but there was a concomitant reduction in depression [28]. The S3 guidelines additionally list olanzapine. A new study also suggests an effect of cariprazine.

In the improvement of depressive symptomatology, the PINES group of effects tended to show a very good effect, as did PIPS & RIP, with brexpiprazole showing significantly less effect. The DONES are more in the midfield. The fact that many medications significantly improve depressive symptoms may be due to a reduction in anxiety and distress associated with schizophrenia. Den-y aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lurasidone, and quetiapine are approved in several countries for major depression, bipolar depression, or both [27].

For improving social function, PINES are rated as good-performing antipsychotics. PIPS&RIP also scored positively here, while there is a clear range from good to no effect for the DONES [27].

Comparing patient adherence among the respective medications, there was a higher rate of treatment discontinuation with clozapine compared with the other antipsychotics. If one considers the clear side effects which can occur e.g. under Clozapin and if one considers that these move in the course of the successful therapy of the positive symptoms more and more into the foreground of the complaint picture of the patients, a possible explanation for the autonomous discontinuation of the medicine seems to lie here [27].

Clozapine and PINES in general had the most sedating effect, followed by DONES. PIPS&RIP perform less sedating. This can also be explained by the receptor action profile. Not all atypical antipsychotics are equally sedating because they do not all have potent antagonist properties at H1-histamine, muscarinic, cholinergic, and α1-adrenergicreceptors. Drugs that have potent effects at all three receptors are most sedating, which is true of clozapine [3,27].

PINES also stand out clearly as the drug group with the most side effects in terms of weight gain, whereas PIPS&RIP had the least impact on body weight [27]. In general, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine do not appear to have the pharmacologic effects associated with weight gain and increased cardiometabolic risk, such as that of increasing insulin resistance [3].

Conclusion

Schizophrenia is a common mental illness with alteration of perception of thinking and self-experience. A disease that has a major impact on the daily lives of those affected and can severely limit quality of life and functionality. There is an increasing number of psychopharmacological therapy options that treat the long-term relevant negative symptoms in addition to the positive symptoms that are initially in the foreground. The treatment of negative symptoms plays a central role in the success of therapy and is essential for improving the patient’s quality of life. For general reduction of positive and negative symptoms, clozapine clearly shows the highest effectiveness, although this drug again can have significant side effects such as weight gain and sedation and therefore also still often results in poor adherence. Therefore, it is classified as a second line. Good adherence is critical to avoid increased hospitalizations for both somatic and psychological reasons. Here, especially the so-called ABC substances (aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine) as representatives of the third generation of antipsychotics, which belong to the partial agonists, seem to be a good option.

Take-Home Messages

- Schizophrenia is a common mental illness with alteration of perception of thinking and self-experience.

- A disease that has a major impact on the daily lives of those affected and can severely limit quality of life and functionality.

- Psychopharmacological treatment of negative symptoms is a key factor in the success of therapy and is essential for improving the patient’s quality of life.

Literature:

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e.V. (ed.) S3-Praxisleitlinien in Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie. (2019) – Schizophrenia treatment guideline. Darmstadt: Steinkopff-Verlag.

- Horst Dilling HJF: ICD-10 classification of mental disorders. Hogrefe Publishers (2019).

- Stahl SM: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th edition, Cambridge University Press (2013).

- Trepel M: Neuroanatomy: structure and function, 7th edition edn, Elsevier, Urban & Fischer, Munich (2017).

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13 (1987): 261-276.

- Bullinger M, Blome C, Sommer R, et al: Health-related quality of life – a key patient-relevant outcome in the benefit assessment of medical interventions. Bundesgesundheitsblatt – Health Research – Health Protection 58 (2015): 283-290.

- Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al: Content validity – establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1 – eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument (2011). Value Health 14: 967-977.

- Bullinger M, Kuhn J, Leopold K, Janetzky W, Wietfeld R (2019) Quality of life as a target criterion in schizophrenia therapy. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 87:348-356.

- Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT, Jr: The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome (1984). Schizophr Bull 10: 388-398.

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. (1998) Psychol Med 28: 551-558.

- Malm U, May PR, Dencker SJ (1981) Evaluation of the quality of life of the schizophrenic outpatient: a checklist. Schizophr Bull 7:477-487.

- Deutschebaur L, Lambert M, Walter M, Naber D, Huber CG (2014) Pharmacological long-term treatment of schizophrenic disorders. The Neurologist 85: 363-377.

- Karow A WL, Schöttle D, et al: The assessment of quality of life in clinical practice in patients with schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 16 (2014).

- Németh G, Laszlovszky I, Czobor P, Szalai E, et al: Cariprazine versus risperidone monotherapy for treatment of predominant negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial (2017). Lancet (London, England) 389: 1103-1113.

- Kemmler G, Hummer M, Widschwendter C, Fleischhacker WW: Dropout rates in placebo-controlled and active-control clinical trials of antipsychotic drugs: a meta-analysis (2005). Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 1305-1312.

- DiBonaventura M, Gabriel S, Dupclay L, et al: A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia (2012). BMC Psychiatry 12: 20.

- Correll CU, Rubio JM, Inczedy-Farkas G, et al: Efficacy of 42 Pharmacologic Cotreatment Strategies Added to Antipsychotic Monotherapy in Schizophrenia: Systematic Overview and Quality Appraisal of the Metaanalytic Evidence (2017). JAMA Psychiatry 74: 675-684.

- Winkelbeiner S, Leucht S, Kane JM, Homan P: Evaluation of Differences in Individual Treatment Response in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-analysis (2019). JAMA Psychiatry 76: 1063-1073.

- Harrow M, Jobe TH, Faull RN: Do all schizophrenia patients need antipsychotic treatment continuously throughout their lifetime? A 20-year longitudinal study (2012). Psychol Med 42: 2145-2155.

- Moncrieff J: Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse (2006). Acta Psychiatr Scand 114: 3-13.

- Jablensky A, Sartorius N: What did the WHO studies really find (2008)? Schizophr Bull 34: 253-255.

- Harrow M, Jobe TH: Does long-term treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications facilitate recovery? Schizophr Bull 39 (2013): 962-965.

- Samaha AN, Seeman P, Stewart J, et al: “Breakthrough” dopamine supersensitivity during ongoing antipsychotic treatment leads to treatment failure over time. J Neurosci 27 (2007): 2979-2986.

- Unger A, Erfurth A, Sachs G: Negative symptoms in schizophrenia and their differential diagnosis. psychopraxis neuropractice 21 (2018): 73-78.

- Wang P, Si T: Use of antipsychotics in the treatment of depressive disorders. Shanghai archives of psychiatry (2013), 25(3), 134-140.

- Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al: Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) (2003). Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 82-91.

- Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, et al: Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis (2019). Lancet (London, England) 394: 939-951.

- Krause M, Zhu Y, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, et al: Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or promi-nent negative symptoms: a systematic review and metaanalysis (2018). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 268: 625-639.

- Benkert O, Hippius H: Compendium of psychiatric pharmacotherapy, edition 13, Berlin.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(5): 6-12.