Neck cysts usually occur unilaterally and in rare cases bilaterally. In particular, if cervical swelling persists for more than 4 weeks, further evaluation with imaging (ultrasound, CT, or MRI) is indicated.

In recent months, numerous articles have already been published on the subject of “dysphagia”, showing how varied the causes of this symptomatology are and what diagnostic measures may be required to identify the underlying disease. The case casuistry presented also demonstrated the effort that is sometimes expended and that the outcome of diagnostics is not always clear. Today’s case report, on the other hand, is one of the simpler and more reliably diagnosable changes that can cause dysphagia: the cervical cyst. Cervical cysts are residuals of the gill ducts and thus congenital anomalies. Of the anomalies of the neck region, they represent about 30% and, depending on the size and location, are asymptomatic in most cases [1,2]. They may occur medially or laterally in the neck region and in 2-3% of cases bilaterally. About 20% of cervical cysts are diagnosed in children and adolescents with swelling in the neck area, and between the ages of 20 and 40 in about 75% of patients. Most neck cysts are asymptomatic. However, local pain, sensation of pressure and phlegm with dysphagia may also determine the clinical picture. Fistula formation is possible, primarily into the tonsillar fossa or caudally to the cutis, extending to periclavicular. Significant inflammatory complications occur rather rarely, but can then lead to a serious symptomatology characterized by the inflammation. As a consequence, a change from the controlling position to minimally invasive or microsurgical therapy is then required.

Radiographs do not play a role in the diagnosis of neck cysts. Although large and superficially located cysts may cause soft-tissue shadowing and, especially in the a.p. projection, asymmetry in the visualization of the neck, exact diagnostic assignment is not possible with the low soft-tissue contrast of the radiographic examination.

Sonographically, especially the superficially located cysts can be detected well [2].

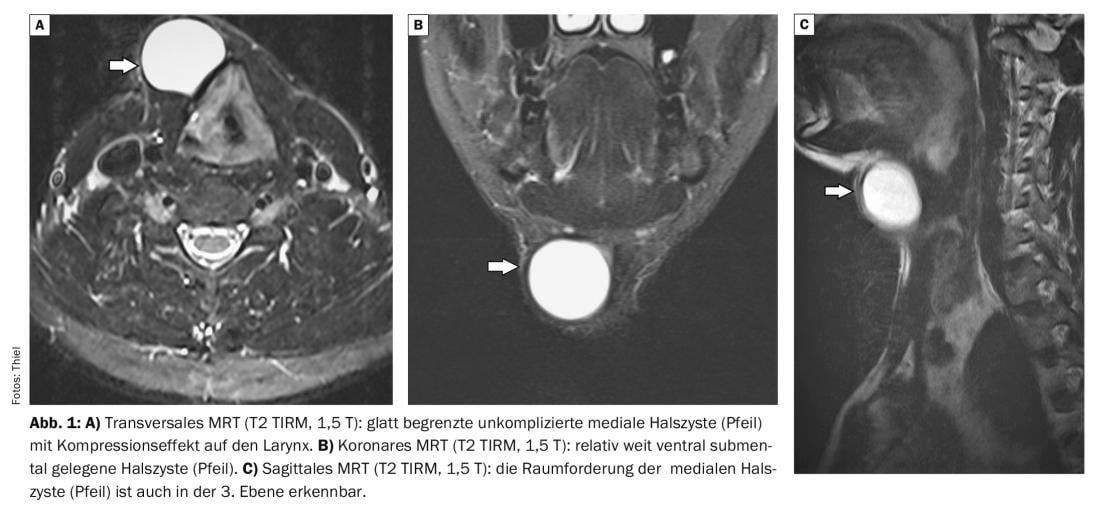

Computed tomographic examinations can delineate cystic processes of the soft tissues of the neck. The uncomplicated cyst is a smoothly confined fluid-equivalent structure with a delicate capsule [4]. If an inflammatory complication is suspected, intravenous contrast application can demonstrate wall thickening of the cyst with enhancement, and fistula formation can also be readily demonstrated by computed tomography with probing of the fistula opening and contrasting of the fistula tract [3].

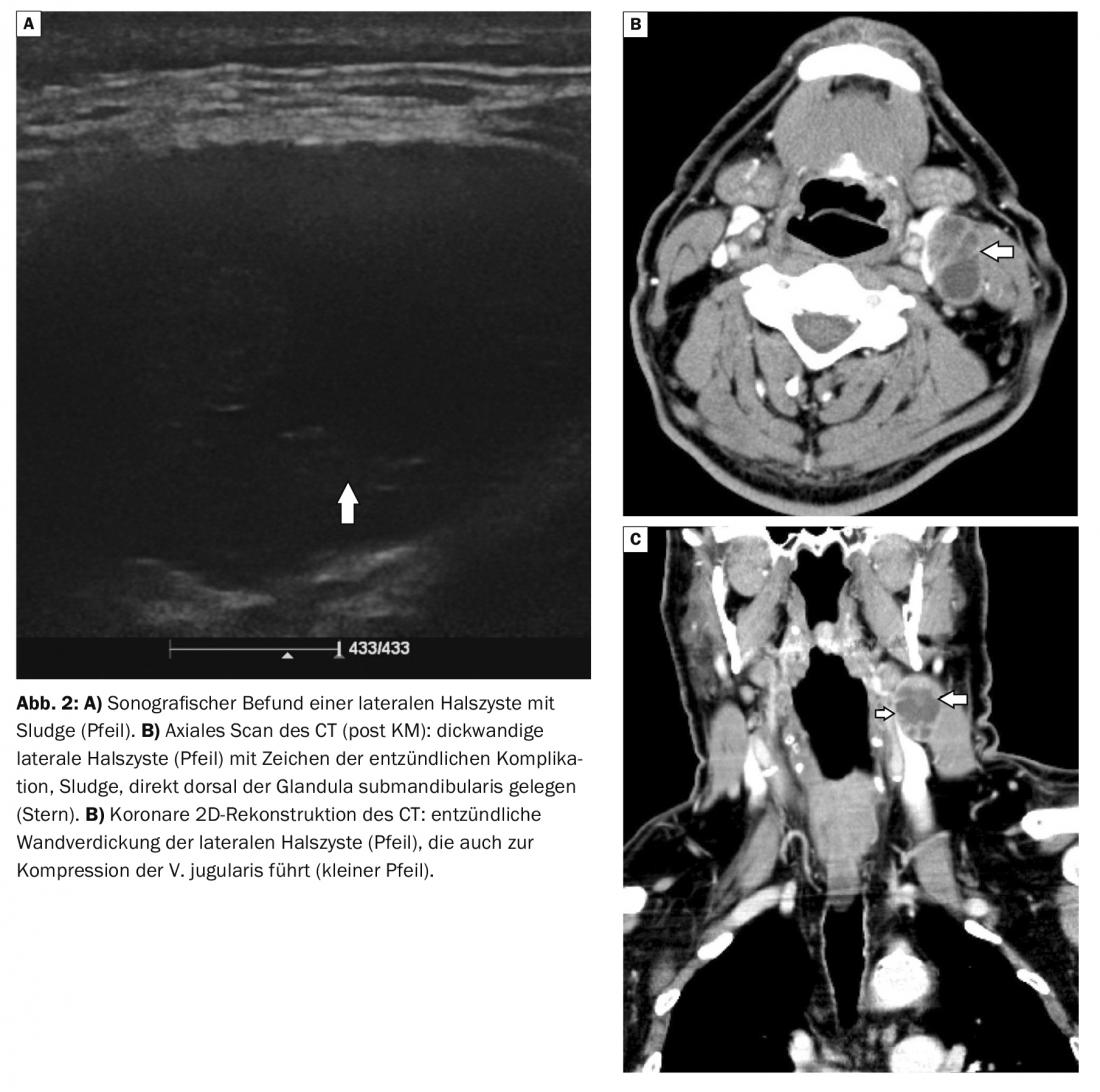

Magnetic resonance imaging also reveals a fluid-equivalent structure in the corresponding sequences. When the protein content of the fluid is high, the signal of the T1w sequence may be intermediate to hyperintense, otherwise hypointense [5]. As in CT diagnostics, if an inflammatory complication of the neck cyst is suspected, intravenous administration of contrast agent leads to a signal increase of the wall and, if the inflammation breaks through, also of the adjacent soft tissue

Case study

The first case report shows a 41-year-old patient with a median cervical cyst (Fig. 1A to C) that led to increasing swelling at the larynx with local sensations of pressure and laryngitis within 6 months.

A 62-year-old man in case 2 complained of recurrent pain and episodes of fever within a short period of time with progressive swelling in the cervical region caudal to the left mandibular angle (Fig. 2A to C) . Laboratory signs of inflammation were positive. The primary sonography performed did not yet show any further inflammatory change except for minor sludge in the lateral cervical cyst. Days later, computed tomographic scans demonstrated a thick-walled cystic space-occupying process without surrounding infiltration, consistent with a complicated lateral cervical cyst.

Take-Home Messages

- Cervical cysts are embryonic relics of the gill arches.

- They may be localized on the neck medially or laterally. Bilateral neck cysts may occasionally occur.

- The main age peak is between 20 and 40 years.

- If the neck cysts are asymptomatic, imaging follow-up is warranted.

- Size progression, neurological or functional symptoms, inflammation or fistulae are reasons for surgical repair.

- Imaging is performed by sonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

Literature:

- Thiel HJ: Anomalies and norm variants. Changes in soft tissue 5.2: Lateral neck cyst. Deutscher Ärzteverlag. MTA Dialog 2019; 20(3): 14-16.

- Bocchialini G, et al: Unusually rapid development of a lateral neck mass: Diagnosis and treatment of a branchial cleft cyst. A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017; 41: 383-386.

- Goff CJ, Allred C, Glade RS: Current management of congenital branchial cleft cysts, sinuses, and fistulae. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012; 20(6): 533-539.

- Alyono JC, et al: Second brachial cleft anomaly with an ectopic tooth: a case report. Ear Nose Throat J 2014; 93(9): E1-3.

- Burgener FA, Meyers SP, Tan RK, Zaunbauer W: Differential diagnosis in MRI. Stuttgart New York: Georg Thieme Verlag 2002; 248-249.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(11): 30-31