Periodic, very painful and extensive lymph node swelling may also indicate a rare Castleman’s disease. The rare disease is divided into unicentric Castleman’s disease (UCD) and multicentric forms. The multicentric form is a serious systemic disease that is not easily diagnosed.

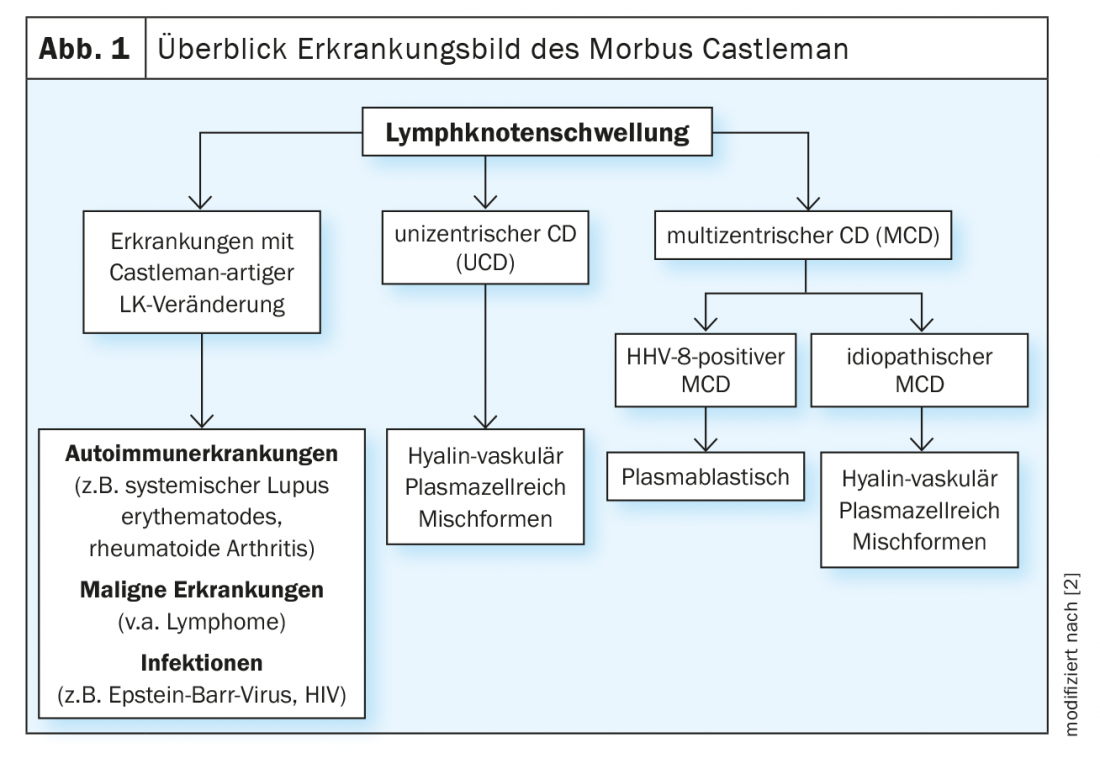

Lymph node swelling occurs quickly and is not a concern per se. On the other hand, if there is periodic, very painful and marked extensive swelling of the lymph nodes, Castleman’s disease should also be considered. The rare disease is differentiated into unicentric Castleman’s disease (UCD) and multicentric forms and is often overlooked. UCD is a benign form of the disease with localized hyperplasia of the lymphoid tissue [1]. In this case, excision of the affected lymph node is the method of choice [2]. In contrast, it becomes more problematic in multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD). This is a serious systemic disease with a frequently unfavorable prognosis. Overproduction of different cytokines, especially interleukin-6 (IL-6), results in a heterogeneous symptomatology. A close association exists with human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8). This in turn is largely congruent with HIV infection. Accordingly, over 90% of HIV-infected patients are also HHV-8 positive. Conversely, in HIV-negative patients, the rate is only 10-15% – in this case, idiopathic MCD predominates [3] (Fig. 1).

Epidemiology

Basically, Castleman’s disease is a very rare disease, which, however, is certainly not correctly diagnosed for the most part. Per million inhabitants, 2.4 cases are expected, which corresponds to about 20 cases in Switzerland [4]. In this context, MCD seems to occur less frequently (approximately 35.4%) than UCD (64.6%) [5]. The incidence is higher in HIV-infected patients. According to a British study, it is 4.3 cases per 10 000 patient-years, with a slight upward trend in recent years [2,6]. In observational studies, mortality in the first 5 years after diagnosis was 30-35% [7]. According to a systemic review, disease-free survival in iMCD at 3 years was 45.7% [8].

Pathogenesis

The multicentric form with enlargement of numerous lymph nodes was first described in 1978. It occurs more frequently in HIV-positive patients. HHV8 is responsible for multicentric Castleman’s disease in nearly all HIV-positive patients and for about half of the disease in HIV-negative patients [9]. They produce a viral interleukin that is very similar to human IL-6 and has similar effects. It only needs to bind to one of the two IL-6 receptor subunits to be active. This explains the much broader effect on target cells and probably also the typical “cytokine storms” [10,11,2]. Interleukin-6 and other proinflammatory cytokines induce proliferation of B cells and plasma cells, secretion of vascular endothelial growth factors, and angiogenesis.

The causes of iMCD, on the other hand, are -currently still controversial. Scientists hypothesize that an inflammatory autoimmune disease, a viral infection, and a genetic predisposition may be responsible [12]. In addition to IL-6, other signaling molecules are involved, including VEGF (“vascular endothelial growth factor”), TNF-alpha, and interleukin-1 [13]. Lymphocytic proliferation in iMCD is usually polyclonal and a consequence of hypercytokinemia [14,2]. However, monoclonal proliferation has certainly been observed in some lesions of the hyaline vascular subtype [15,2].

Symptoms and complaints

Symptoms present very heterogeneously, which often makes effective diagnosis difficult. Generally, however, the disease is accompanied by pain of the affected lymph nodes. These swellings often occur episodically, especially in HHV-8 positive MCD. These are joined by clear B symptoms such as fever, night sweats and weight loss. Almost all patients complain of weakness and a feeling of illness, nausea, vomiting and loss of appetite. In addition, the spleen and liver appear enlarged. In addition, there is hepatomegaly, respiratory symptoms, and a tendency to edema with hypalbuminemia. There is usually severe anemia hematologically, which can often be accompanied by massive thrombocytopenia.

Typically, the disease progresses in episodes lasting several days to weeks, during which patients often have high fevers and are severely ill. In between, there are longer periods, lasting quite a few weeks, during which the patients feel much better again. The size of the lymph nodes may become almost normal. Frequency and intensity of relapses generally increase over time, although self-limiting courses are also known. However, there is a significantly increased risk of malignant lymphoma, especially rather rare lymphoma subtypes such as plasmablastic lymphoma or primary effusion lymphoma [2,12].

An iMCD manifests itself in a pronounced fatigue symptom, especially in the early stages. In contrast to MCD, symptoms such as fever, lymph node swelling, and anemia are much less pronounced and the relapsing course is less abrupt. The symptoms can range from mild constitutional symptoms to life-threatening courses with anasarca and multiple organ failure. A severe iMCD subtype, TAFRO syndrome, has been newly defined. This is a symptom complex of thrombocytopenia, ascites, fever, reticular fibrosis in the bone marrow, and organomegaly with normal γ-globulin [16]. In addition, associations with POEMS syndrome, a clinical picture consisting of peripheral neuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin lesions, are common [2].

Diagnostics

Castleman’s disease must be differentially diagnosed from lymphoma and other severe diseases. The severe form in particular is often mistaken for lymphoma. Histopathological examination of an extirpated lymph node is obligatory. A puncture is usually not sufficient. The preparation shows reactive lymphadenitis with plasma cell proliferation in the pulp and regressive changes in the germinal centers, which are usually layered like onion skins and interspersed with vessels. In HHV-8 positive MCD, a plasmablastic image is usually seen, often with a so-called moth-eaten pattern in the mantle zone. The characteristic onion skin pattern is often partially destroyed. Detection of HHV-8 is by staining for LANA-1 (“latency-associated-nuclear-antigen”). Blood drawn during a disease episode shows elevated IL-6 and CRP levels. The triad of B-symptomatology, HHV-8 viremia and histological findings are useful for diagnosis [17].

Diagnosis of iMCD is much more difficult because a variety of other diseases must be excluded. The histopathologic changes are also found, for example, in a variety of infections (including Epstein-Barr virus) or in lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, and some neoplasms, most notably malignant lymphomas. Therefore, in addition to histopathologic changes, clinical and laboratory parameters must always be considered. iMCD is differentiated into three histopathological subtypes: the hyaline vascular type, the plasma cell type, and the mixed type. All occur in about 20-40% of cases [18]. In the hyaline vascular type, dysplastic follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and atrophic germinal centers interspersed with hyaline vessels, around each of which lymphocytes are concentrically arranged. In the plasma cell type, the germinal centers are hyperplastic rather than atrophic and the FDCs and lymph node architecture are normal [2].

Therapy

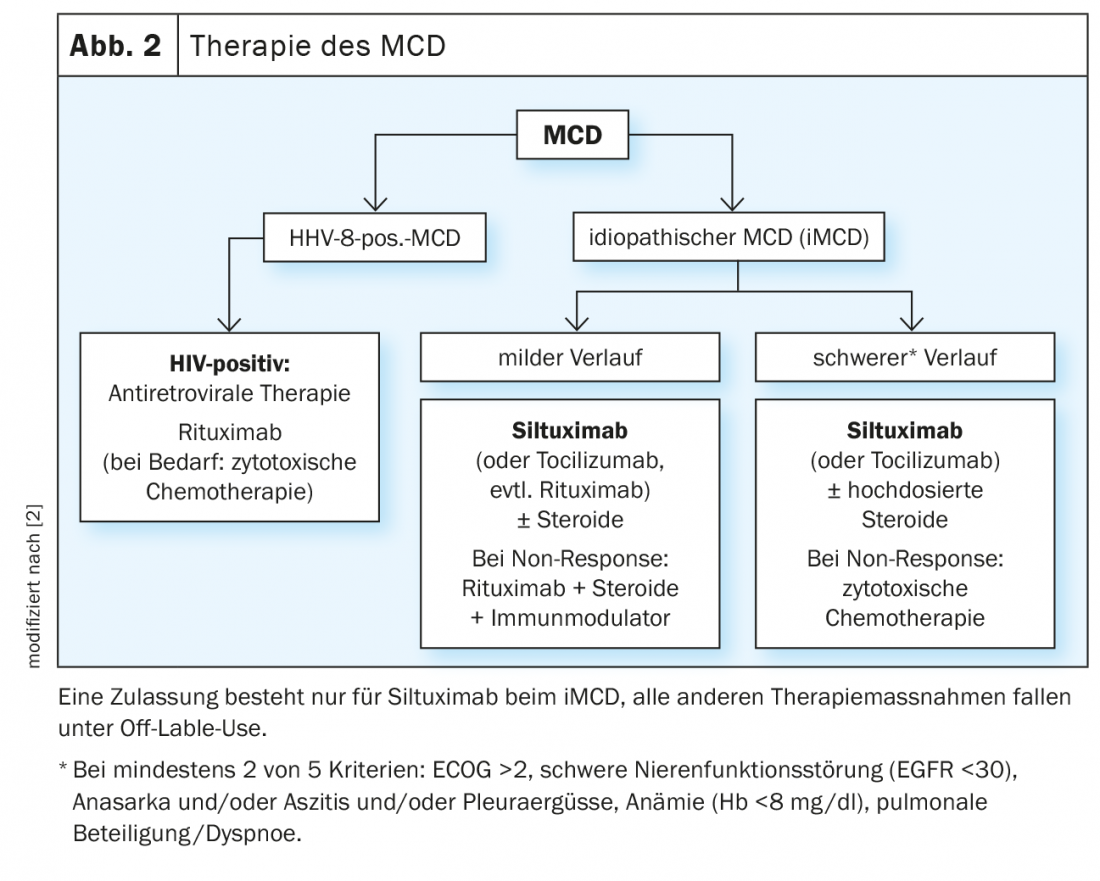

Unicentric Castleman’s disease has a very good prognosis because surgical intervention can remove the affected lymph node. Recurrence of the disease is extremely rare. However, since many lymph nodes are involved in MCD, surgical intervention is not goal-directed. Treatment remains difficult. There is no standard therapy for patients with multicentric Castleman’s disease. Conceptually, immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents are used. Glucocorticoids are effective but often do not result in long-term symptom improvement (Fig. 2).

In iMCD, blockade of the IL-6 signaling pathway using monoclonal antibodies such as siltuximab is primarily used. In HHV-8 positive MCD, cytotoxic elimination of the cells responsible for cytokine overproduction is emphasized. Immunomodulatory therapies are primarily steroids, as well as antiviral agents such as valganciclovir. Consensus-based recommendations for iMCD [19] have been in place for the first time since 2018. They are based on experience with 344 patients who underwent a total of 479 therapies, take into account disease severity, prior therapies, and response.

The only drug approved to date for the treatment of iMCD is siltuximab, a monoclonal antibody against human IL-6, which is used for all forms of iMCD with or without steroids. In the pivotal study, 79 iMCD patients were treated with either siltuximab or placebo for three weeks [20,7]. The primary endpoint was a durable response in terms of tumor size and improvement in a clinical symptom score over at least 18 weeks. While no response was observed in the placebo group, rates in the verum group were 34%. Siltuximab was well tolerated overall. Common and characteristic side effects include skin itching, upper respiratory tract infections, exanthema, and local edema, predominantly at severity levels 1 and 2. Severe side effects include fatigue (12%) and night sweats (8%). However, the rate here was not higher than with placebo, so that these symptoms are more likely to be attributable to the underlying disease [7]. Recent trial data now demonstrate that newly diagnosed and pretreated MCD patients respond equally to the compound [21]. A total of 46 pretreated affected individuals and 33 newly diagnosed patients were randomized to either the antibody (n=53) or placebo (n=26). With the exception of histologic subtype, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics. The median treatment duration was 375 bzs. 233 days. Rates of durable tumor response and symptomatic response were 34.5% vs. 0% in patients treated with siltuximab compared with placebo in those previously treated and newly diagnosed 33.3% vs. 0%, respectively. The median time to treatment failure (TTF) was not reached with siltuximab in either subgroup.

Tocilizumab, an antibody against the IL-6 receptor, is considered an alternative to siltuximab in international recommendations, but is approved in Europe only for rheumatoid arthritis.

Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody against CD20, is also not approved for the treatment of MCD. Especially patients with HHV-8 positive MCD seem to respond well to it. Significant improvement in overall survivala and disease-free survival was observed in several case series. Cytokines, but also CRP, immunoglobulins and HHV-8 viral load decreased [22,2]. However, progression of Kaposi’s sarcoma, which often accompanies the disease, has occurred in about one-third of cases. Here, a combination with KS-active cytostatic agents might be useful [23]. In life-threatening situations, splenectomy should be considered. It reduces the pool of HHV-8-infected cells [2].

Take-Home Messages

- Castleman disease is divided into the unicentric benign form (UCD) and multicentric Castleman disease (MCD).

- MCD is a systemic disease that is often unrecognized due to its heterogeneity and rare occurrence.

- Painful swelling of the lymph nodes occurs in episodes, often accompanied by B symptoms such as fever or night sweats.

- Currently, siltuximab is the only drug approved for the treatment of idiopathic MCD.

Literature:

- Castleman B, Towne VW: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital; weekly clinicopathological exercises. N Engl J Med 1954; 251: 396-400.

- Hoffmann C, Tiemann M: Multicentric Castleman’s disease: rarely correctly diagnosed. Dtsch Arztebl 2019; 116(46): [32]; DOI: 10.3238/PersOnko.2019.11.15.06

- Hoffmann C: Multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) – a rare, often unrecognized clinical picture. Trillium 2015. www.trillium.de/zeitschriften/trillium-krebsmedizin/archiv/ausgaben-2015/heft-12015/multizentrischer-morbus-castleman-mcd-ein-seltenes-oft-verkanntes-krankheitsbild.html (last accessed on 06.04.2020)

- Robinson D Jr, Reynolds M, Casper C, et al: Clinical epidemiology and treatment patterns of patients with multicentric Castleman disease: results from two US treatment centres. Br J Haematol 2014; 165: 39-48.

- Haap M, Wiefels J, Horger M, et al: Clinical, laboratory and imaging findings in Castleman’s disease-The subtype decides. Blood Rev 2018; 32: 225-234.

- Powles T, Stebbing J, Bazeos A, et al: The role of immune suppression and HHV-8 in the increasing incidence of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman’s disease. Ann Oncol 2009; 20: 775-779.

- www.dgho.de/publikationen/stellungnahmen/fruehe-nutzenbewertung/siltuximab/siltuximab-dgho-stellungnahme-20141006.pdf (last accessed on 06.04.2020)

- Talat N, Schulte KM: Castleman’s disease: systematic analysis of 416 patients from the literature. Oncologist 2011; 16:1316-24

- Fajgenbaum DC, van Rhee F, Nabel CS: HHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis and therapy. Blood 2014; 123: 2924-2933. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-545087.

- Li H, Wang H, Nicholas J. Detection of direct binding of human herpesvirus 8-encoded interleukin-6 (vIL-6) to both gp130 and IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and identification of amino acid residues of vIL-6 important for IL-6R-dependent and -independent signaling. J Virol 2001; 75: 3325-3334.

- Moore PS, Boshoff C, Weiss RA, Chang Y: Molecular mimicry of human cytokine and cytokine response pathway genes by KSHV. Science 1996; 274: 1739-1744.

- https://medlexi.de/Morbus_Castleman (last accessed on 06.04.2020)

- Pierson S, Stonestrom A, Ruth J, et al: Quantification of plasma proteins from idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease flares and remissions reveals ‘chemokine storm’ and separates clinical subtypes (abstract). Blood 2017; 130(Suppl. 1).Abstract 3592

- Ohyashiki JH, Ohyashiki K, Kawakubo K, et al. Molecular genetic, cytogenetic, and immunophenotypic analyses Castleman’s disease of the plasma cell type. Am J Clin Pathol 1994; 101: 290-295.

- Chang KC, Wang XC, Hung YL: Monoclonality and cytogenetic abnormalities in hyaline vascular Castleman disease. Mod Path 2014; 7: 823-831.

- Iwaki N, Fagenbaum D, Nabel CS, et al: Clinicopathologic analysis of TAFRO syndrome demonstrates a distinct subtype of HHV-8-negative multicentric Castleman disease. Am J Hematol 2016; 91: 220-226.

- Bower M, Pria AD, Coyle C, et al: Diagnostic criteria schemes for multicentric Castleman disease in 75 cases. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 65(2): e80-82.

- Liu AY, Nabel CS, Finkelman BS, et al: Idiopathic multicentric Castleman’s disease: a systematic literature review. Lancet Hematol 2016; 3: e163-175.

- van Rhee F, Voorhees P, Dispenzieri A, et al: International, evidence-based consensus treatment guidelines for idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood 2018; 132: 2115-2124.

- van Rhee F, Wong RS, Munshi N, et al: Siltuximab for multicentric Castleman’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 966-974, DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70319-5.

- van Rhee F, Rossi J, Simpson D et al. Newly diagnosed and previously treated multicentric Castleman disease respond equally to siltuximab. Br J Haematol. 2021; 192(1):e28-e31.

- Bower M, Veraitch O, Szydlo R, et al: Cytokine changes during rituximab therapy in HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood 2009; 113: 4521-4524.

- Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Aleman K, et al: Rituximab plus liposomal doxorubicin in HIV-infected patients with KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood 2014; 124: 3544-3552.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2022; 10(2): 10-13.