Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease in the Western world. In distinction to alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol consumption in NAFLD should be at a generally safe level, i.e., <20 grams/day in women and <30 grams/day in men. With the increasing prevalence of obesity and associated diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea, the prevalence of NAFLD has also increased significantly in recent years.

Etiology and risk factors

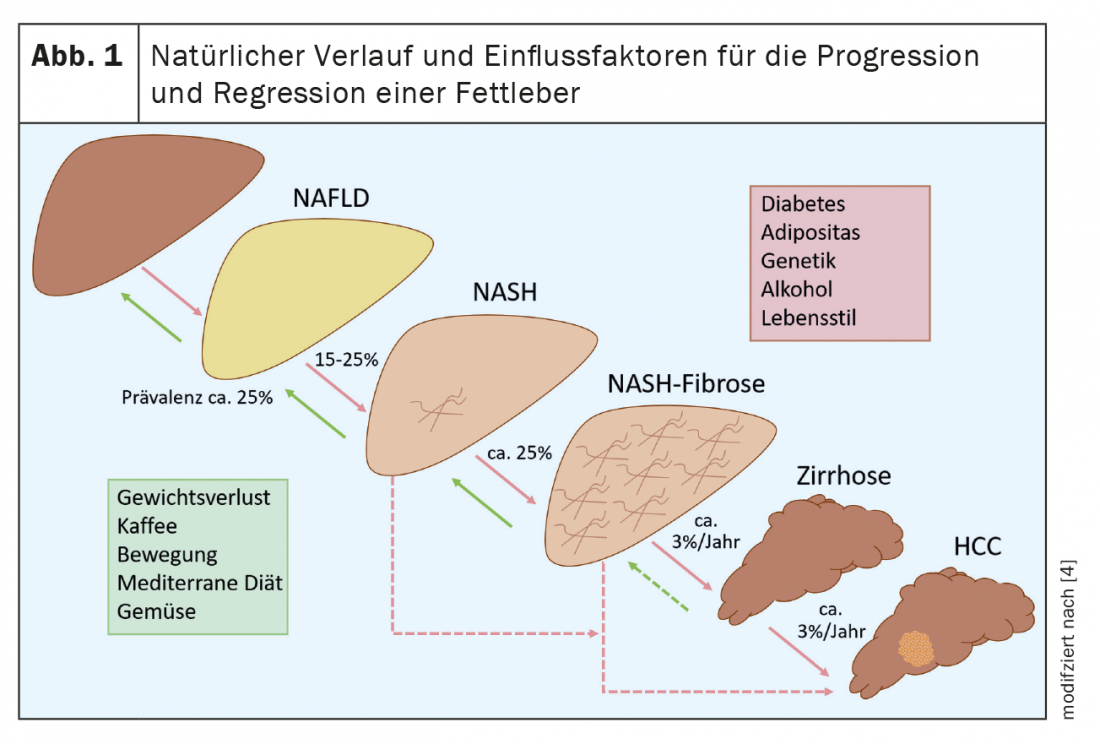

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease in the Western world. In distinction to alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol consumption in NAFLD should be at a generally safe level, i.e., <20 grams/day in women and <30 grams/day in men. In countries with high proportions of people who are overweight and obese, approximately one-quarter to one-third of adults have NAFLD (Fig.1). With the increasing prevalence of obesity and associated diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea, the prevalence of NAFLD has also increased significantly in recent years. For example, while NAFLD affected 6% of adults in the United States in 2003, this number increased to 18% by 2011 and is currently close to 25% [1]. In at-risk populations, i.e., patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, the prevalence of NAFLD even exceeds 50% [2]. The global increase in consumption of sweet beverages, particularly those high in fructose, has also contributed to the rise in prevalence rates of NAFLD. Because of these clear metabolic risk factors, NAFLD is also referred to as the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. To be distinguished from this are other causes that can lead to hepatic steatosis, such as rapid weight loss, total parenteral nutrition, hepatitis C genotype 3 infection, Wilson’s disease, and certain medications (e.g., methotrexate). Evidence for genetic risk factors has been provided by studies with monozygotic twins and studies in families, which have shown that the risk of first-degree relatives also developing NAFLD is up to 50%. Patients of Asian and South American origin are particularly affected [3]. In addition, risk genes, such as patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3), transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2), 17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13), membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain-containing 7 (MBOAT7), or transmembrane channel-like 4 (TMC4), exist to influence hepatic steatosis and fibrosis development in a proportion of NAFLD patients. It is possible that the determination of genetic risk variants can be used for risk stratification in the future, but they do not yet play a role in clinical practice.

The vast majority of NAFLD patients present with pure hepatic steatosis, and approximately 15% to 25% of these cases may progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [4]. (Fig.1). A proportion of these patients develop relevant liver fibrosis and up to 12% of patients with NASH subsequently develop liver cirrhosis [2]. This increases the risk of hepatic decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), each of which significantly increases the morbidity and mortality of NAFLD. Therefore, it is important to identify patients at risk for progressive disease or with existing advanced fibrosis for early treatment and HCC screening. Under adequate therapy, stabilization or even regression of the disease is possible. This again illustrates the importance of diagnosis. However, recent data from a large German health database show that NAFLD is significantly underdiagnosed [5].

The mortality of patients with NAFLD is largely determined by cardiovascular disease, so the cardiovascular risk of these patients should be reviewed annually, for example, using the AGLA risk calculator of the Swiss Association for Atherosclerosis Prevention. NAFLD also represents an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Screening, diagnostics and surveillance

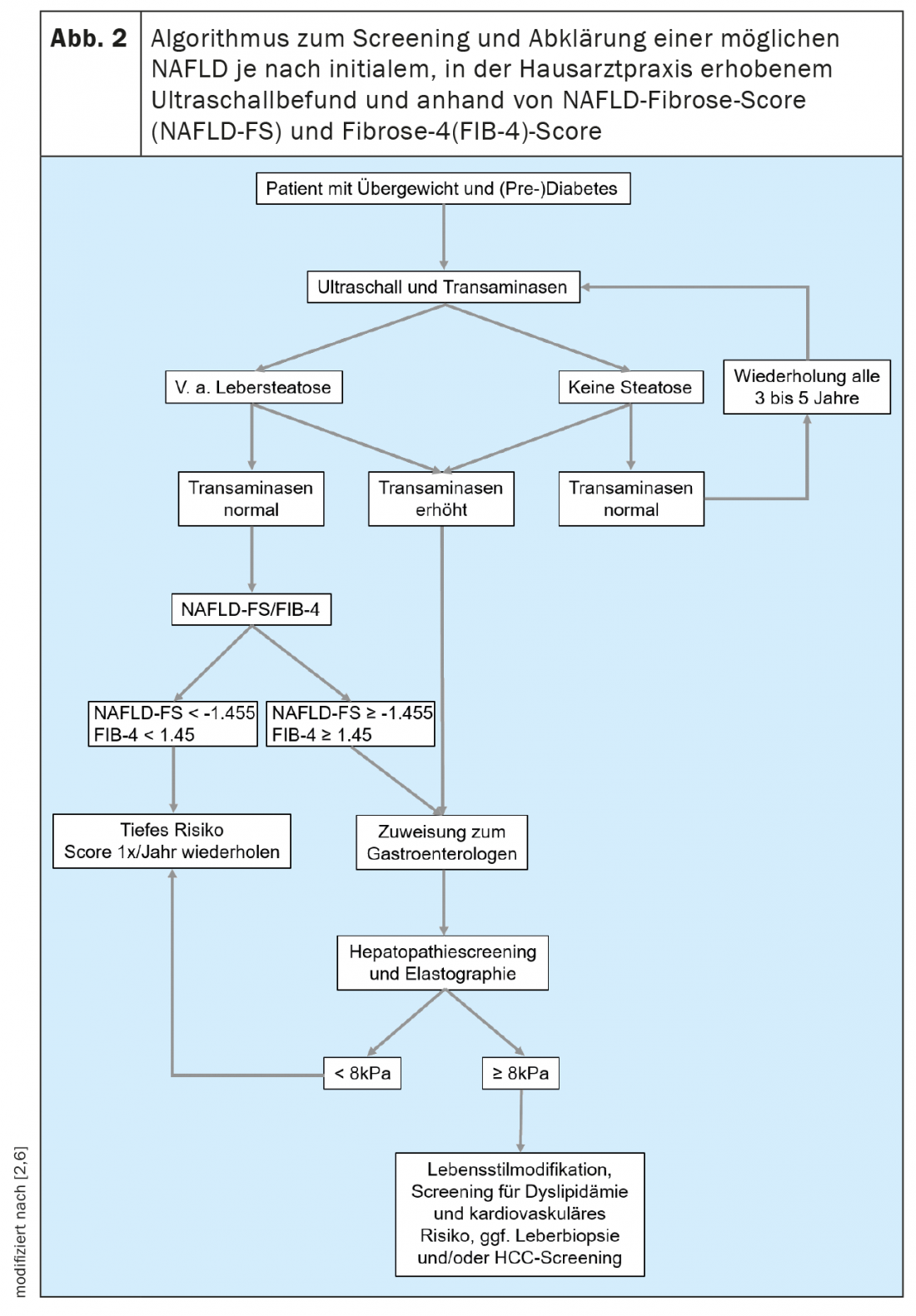

The suspected diagnosis of NAFLD is made after exclusion of other causes of liver disease (especially chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic or autoimmune liver disease) and in the presence of a metabolic risk profile with concomitant evidence of steatosis on ultrasonography. The current guidelines list a liver biopsy for the detection of steatosis, although due to the invasiveness and the high number of patients in clinical practice, the above-mentioned procedure using sonography has become accepted [6]. Sonographically, steatosis can only be detected from about 20% fatty degeneration. The next diagnostic step is to assess whether liver fibrosis is already present, as this will determine the patient’s prognosis. Regardless of the presence of inflammatory activity (NASH), patients with existing liver fibrosis have significantly higher overall and liver-related long-term mortality than patients without fibrosis [7].

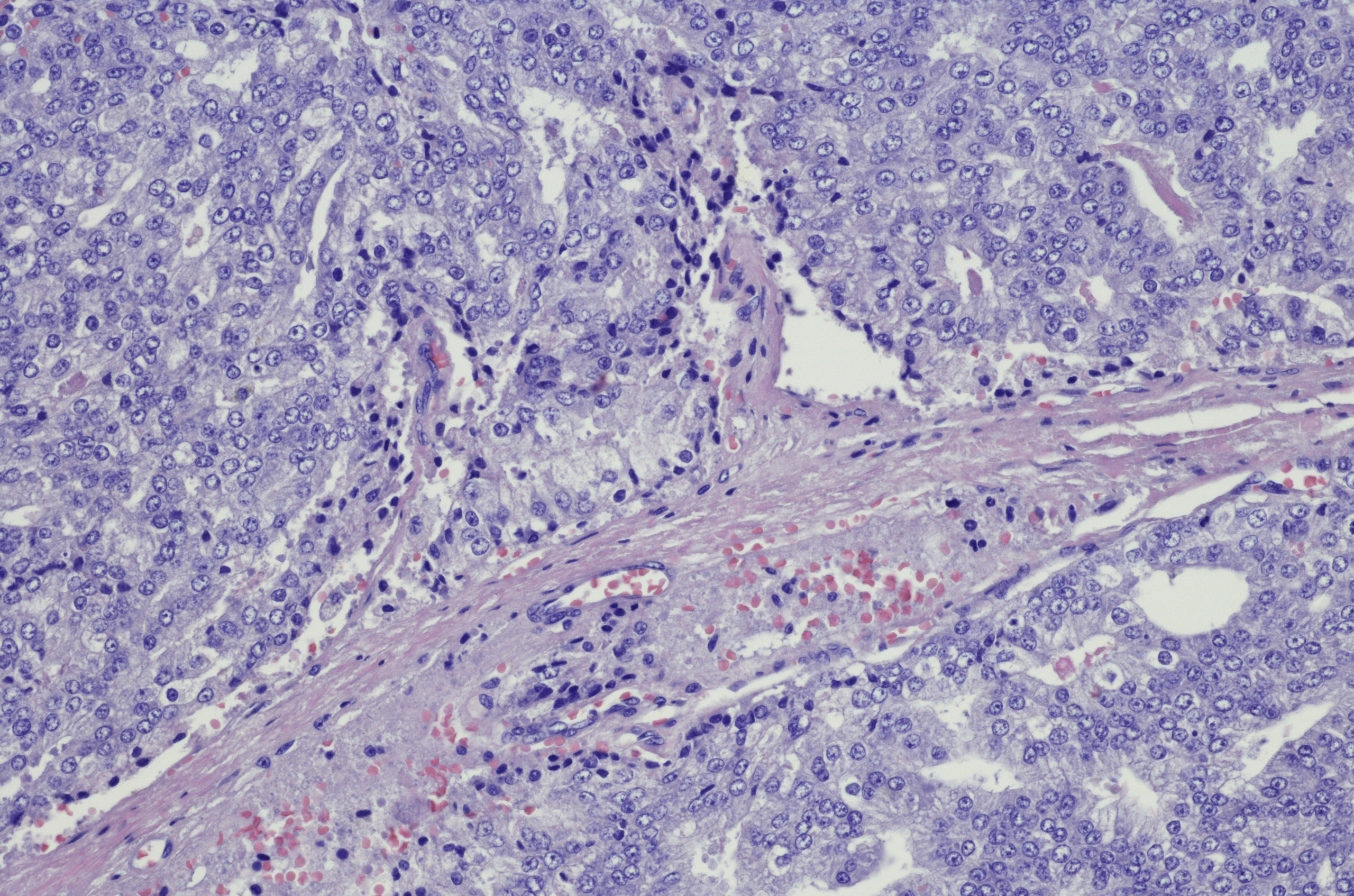

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for fibrosis diagnosis. Histologically, 5 stages of fibrosis are distinguished: F0 = no fibrosis to F4 = cirrhosis. In addition, histology is the only way to differentiate between the presence of NAFLD and NASH. In NAFLD, more than 5% of hepatocytes are affected by steatosis [6]. In NASH, ballooned hepatocytes and infiltrates with inflammatory cells are also found [8]. The extent of these changes is summarized in the so-called NAFLD activity score (NAS). If this score is 5 or more, the diagnostic criteria for NASH are met. Such changes then also favor fibrosis formation up to cirrhosis. Liver biopsy is usually performed by a specialist in gastroenterology and hepatology when there is a specific question. It can be performed when higher-grade fibrosis is suspected in noninvasive fibrosis diagnostics (Fig. 2) or for differential diagnosis in the case of a possible concomitant other cause of liver disease, as this is relevant for the therapy and monitoring of the patient.

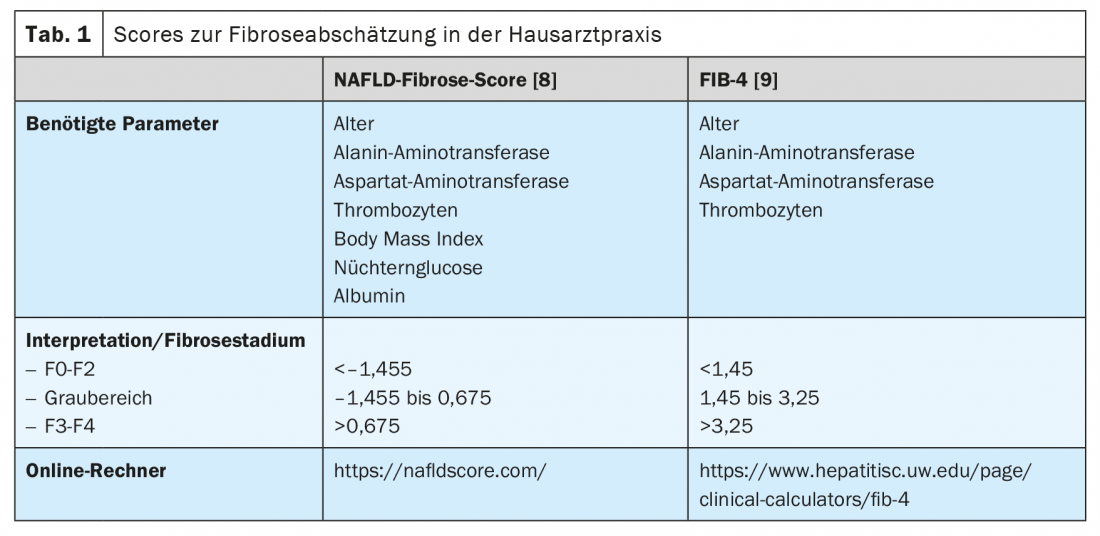

In addition, there are noninvasive ways to assess the presence and extent of liver fibrosis. This will allow colleagues who frequently treat patients in the populations at risk for NAFLD, such as primary care physicians, endocrinologists, and cardiologists, to perform simple screening. In general, it is recommended that NAFLD screening be initiated by ultrasonography in all patients who belong to one of the at-risk populations (Fig. 2). If hepatic steatosis is suspected, transaminases and other clinical parameters, such as body mass index, age and blood count, should be determined to assess the risk of existing higher-grade liver disease. Many scores based on clinical or serum values exist that can be used primarily to rule out advanced liver disease. Of these, the NAFLD Fibrosis Score -(NAFLD-FS) and the Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) are sufficiently validated to be recommended here (Table 1) [9,10]. Values of NAFLD-FS and FIB-4 in the range of F0 to F2 fibrosis virtually exclude severe liver disease. If these scores raise the suspicion of higher grade hepatic fibrosis (scores in the gray range, or in the range of F3 or F4 fibrosis), referral to a gastroenterologist for advanced diagnostics using transient elastography (FibroScan®) or shear wave elastography and, if necessary, liver biopsy can be performed. (Fig. 2). Using the velocity of propagation of an ultrasound pulse in the liver, transient or shear wave elastography can be used to non-invasively assess the degree of liver fibrosis and also to diagnose progression during therapy. Patients with obesity, type 2 diabetes, or prediabetes and elevated transaminases should generally be referred to a specialist in gastroenterology and hepatology for abdominal ultrasonography with elastography because of the high prevalence of NAFLD in this population [11,6]. In the context of transient elastography, a surrogate for hepatic steatosis is also determined simultaneously by means of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP). This CAP value may indicate steatosis if elevated above 275 dB/m, but this method is not currently recommended for the sole initial diagnosis of hepatic steatosis because of insufficient data [12].

Patients with cirrhosis are at increased risk for developing HCC and should receive biannual HCC screening. If sonographic visibility is good, this is done by ultrasound, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) should also be determined as a tumor marker. If visibility is difficult, for example due to concomitant obesity, an MRI of the liver can be performed (alternately if necessary). In a proportion of patients, HCC occurs before development of cirrhosis, but general HCC screening for NAFLD patients without cirrhosis is not considered cost-effective because of the large number of patients. In general, HCC screening is recommended from the presence of F3 fibrosis (“bridging fibrosis”).

Therapy options

Therapy for NAFLD/NASH aims to prevent progression of the disease or to achieve fibrosis regression and also to reduce the cardiovascular risk of patients. Numerous drug therapy trials including phase 3 trials have been conducted in recent years, but no specific therapy has yet been approved. The compounds studied include metabolic, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic therapeutic approaches. Obeticholic acid, a farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist, was shown to improve liver fibrosis in the only positive phase 3 trial to date (REGENERATE) [13]. This substance is already on the market for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (Ocaliva®); an approval with the indication NASH is pending. Current studies are also investigating the combination of different preparations. Prevention of disease progression appears to be easier to achieve than regression of liver fibrosis. Drug therapy could be useful especially for patients with advanced disease, but so far a pharmacological cure is not yet possible [6].

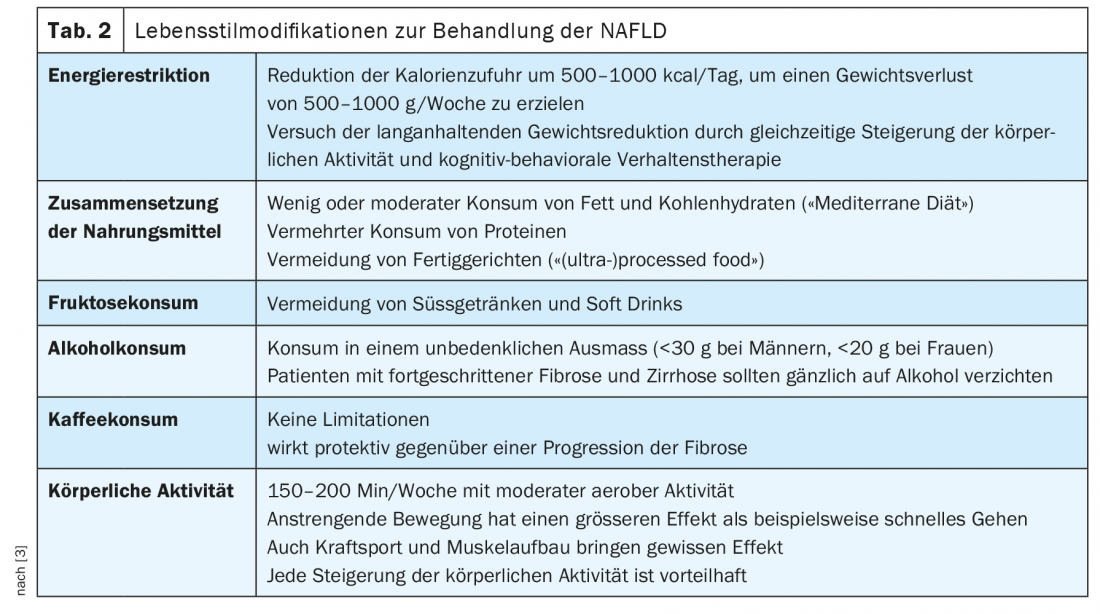

Therefore, the focus of therapy for NAFLD is weight loss with lifestyle changes. Studies have shown significant effects on the degree of fatty liver disease and inflammation, and in some cases fibrosis regression. This therapeutic approach also has a positive effect on relevant co-morbidities, such as diabetes, sleep apnea syndrome, or increased cardiovascular risk. The German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the European Liver Disease Society recommend a weight reduction of 7 to 10%, which should be achieved by dietary changes (avoiding foods that promote the development of NAFLD) and increasing physical activity, see also Table 2 [6,14]. Endurance training and strength training are both effective, so this can be designed according to the patient’s preferences. Thus, an effective therapy for NAFLD is available, but the implementation of the recommendations and achievement of a permanent weight reduction is often difficult for the patient in everyday life. A multidisciplinary approach, especially for patients at risk for a progressive course or already advanced disease, including nutritional counseling and endocrinology with obesity consultation, is useful.

In this sense, bariatric surgery is also listed as a possible therapeutic option when there is an indication for surgery with regard to a present obesity. It has been shown that after bariatric surgery there is a significant decrease in inflammatory activity in a majority of patients and fibrosis regression is also possible [15].

If co-morbidities are present, they should be treated according to the current recommendations of the respective professional societies. No recommendations currently exist for the use of lipid-lowering agents, statins, biguanides, SGLT2 inhibitors, or GLP1 agonists in patients with NAFLD without the appropriate co-morbidity, but data exist showing benefit, ie, regression of steatosis and inflammation, in NAFLD patients [16,17]. If administration of statins is indicated based on lipid profile, they can also be used in patients with NAFLD without increased risk as long as compensated liver function is present. In the presence of Child A cirrhosis, depending on the preparation, there may be a marked increase in bioavailability, so that dose adjustment must be evaluated and regular monitoring of creatine nase should be performed, as the risk of rhabdomyolysis is slightly increased.

Patients with fatty liver and metabolic syndrome often also have high serum ferritin levels in the presence of normal transferrin saturation or absence of a gene mutation compatible with hemochromatosis. In these patients, the benefit of phlebotomy to deplete iron stores is controversial and cannot be recommended due to limited data [6]. Hyperferritinemia in these patients is an expression of steatohepatitis.

If NASH progresses to decompensated cirrhosis, there is an option to evaluate liver transplantation. Meanwhile, NASH cirrhosis is already the most common cause of liver transplantation in the United States.

MAFLD– what is it?

Differentiation between alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is often difficult. As mentioned earlier, NAFLD is a diagnosis of exclusion. However, it is often not possible to differentiate the role of alcohol consumption or other coexisting liver disease from NAFLD, for example, in a patient with obesity, diabetes and chronic hepatitis B. For this reason, there is an effort to use the term metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) Introduce new terminology emphasizing etiology. This definition takes into account concomitant metabolic diseases and the presence of other liver diseases is not a contraindication for diagnosis [18]. MAFLD can be diagnosed when hepatic steatosis is present (imaging or biopsy) with additional obesity (body mass index

≥

25 kg/m²) or type 2 diabetes. In normal-weight individuals, 2 metabolic syndrome factors (hip circumference >101 and 87 cm in men and Women, hypertension >130/85 mmHg, hypertriglyceridemia >1.7 mmol/l, HDL cholesterol <1.0 and 1.3 mmol/l in men and women, respectively, prediabetes with HbA1c of 5.7 to 6.4%, CRP >2 mg/l) should be present. This definition is used to some extent, but has not yet become established in the present guidelines of the professional societies and in clinical practice.

Take-Home Messages

- The prevalence of NAFLD has increased significantly in recent years.

- Patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome are at high risk of developing NAFLD.

- Screening of these at-risk populations by treating primary care physicians for the presence of NAFLD and estimation of disease stage are important for early detection of advanced liver disease and initiation of treatment.

- The NAFLD fibrosis score and FIB-4 are screening methods for fibrosis assessment and can be performed without the need for instrumentation.

- Regular screening for cardiovascular disease should be performed in patients with NAFLD.

- The basis of the therapy is a change in lifestyle with increased physical activity and dietary changes with the aim of reducing weight by about 7 to 10%.

- Drug therapies are being investigated in trials; to date, there is no approved drug for the treatment of NAFLD.

Literature:

- Arshad T, Golabi P, Henry L, Younossi ZM: Epidemiology of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in North America. Curr Pharm Des 2020; 26: 993-997.

- Vieira Barbosa J, Lai M: Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Screening in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in the Primary Care Setting. Hepatol Commun 2021; 5: 158-167.

- Eslam M, Valenti L, Romeo S: Genetics and epigenetics of NAFLD and NASH: Clinical impact. J Hepatol 2018; 68: 268-279.

- Tacke F, Weiskirchen R: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-related liver fibrosis: mechanisms, treatment and prevention. Ann Transl Med 2021; 9(8): 729.

- Canbay A, Kachru N, Haas JS, et al: Patterns and predictors of mortality and disease progression among patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020; 52: 1185-1194.

- European Association for the Study of the L, European Association for the Study of D, and European Association for the Study of O. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016; 64: 1388-1402.

- Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al: Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 389-397.

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al: Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41: 1313-1321.

- Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al: The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007; 45: 846-854.

- Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al: Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2006; 43: 1317-1325.

- American Diabetes A. 4. Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care 2021; 44: 40-52.

- European Association for the Study of the L, List of panel m, Berzigotti A, Boursier J, Castera L, et al: Easl Clinical Practice Guidelines (Cpgs) On Non-Invasive Tests For Evaluation Of Liver Disease Severity And Prognosis – 2020 Update. J Hepatol 2021.

- Younossi ZM, Ratziu V, Loomba R, et al: Obeticholic acid for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: interim analysis from a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 2184-2196.

- Roeb E, Steffen HM, Bantel H, et al: [S2k Guideline non-alcoholic fatty liver disease]. Z Gastroenterol 2015; 53: 668-723.

- Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Ntandja-Wandji LC, et al: Bariatric Surgery Provides Long-term Resolution of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Regression of Fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 1290-1301.

- Lai LL, Vethakkan SR, Nik Mustapha NR, et al: Empagliflozin for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Dig Dis Sci 2020; 65: 623-631.

- Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, et al: A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1113-1124.

- Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J, International Consensus P: MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1999-2014.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(10): 4-8