Lifestyle modification alone is usually not sufficient in type 2 diabetes. Metformin is still considered the first-line drug. However, SGED and international professional societies recommend early combination with an SGLT-2 inhibitor and/or a GLP-1 receptor agonist. These two new classes of compounds have repeatedly demonstrated additional cardiovascular and nephroprotective benefits.

Around 90% of all adult diabetics are affected by type 2 diabetes, i.e. insufficient action of insulin on the body’s cells (insulin resistance). A key message of current therapy studies is that multimodal individually adapted treatment is most promising in type 2 diabetes. The effectiveness of the therapy should be optimal and the burdens as low as possible. HbA1c is currently still considered the standard glycemic target for long-term therapy management. It is important to strive for optimal blood glucose control in patients with newly diagnosed diabetes, according to Prof. Dr. Michael Brändle, Head of the Department of General Internal Medicine/House Medicine at the Cantonal Hospital of St. Gallen [1]. Specifically, this means HbA1c<7% and avoidance of hypoglycemia. However, in modern diabetes therapy, in addition to glycemic control, an additional reduction of micro- and macrovascular complications is aimed for, which is why new substance classes with a corresponding efficacy profile have received a higher priority. And for good reason. “Diabetes mellitus is a relevant cardiovascular risk factor,” emphasizes Prof. Brändle [1].

Multimodal therapy involving SGLT-2-i and/or GLP-1-RA.

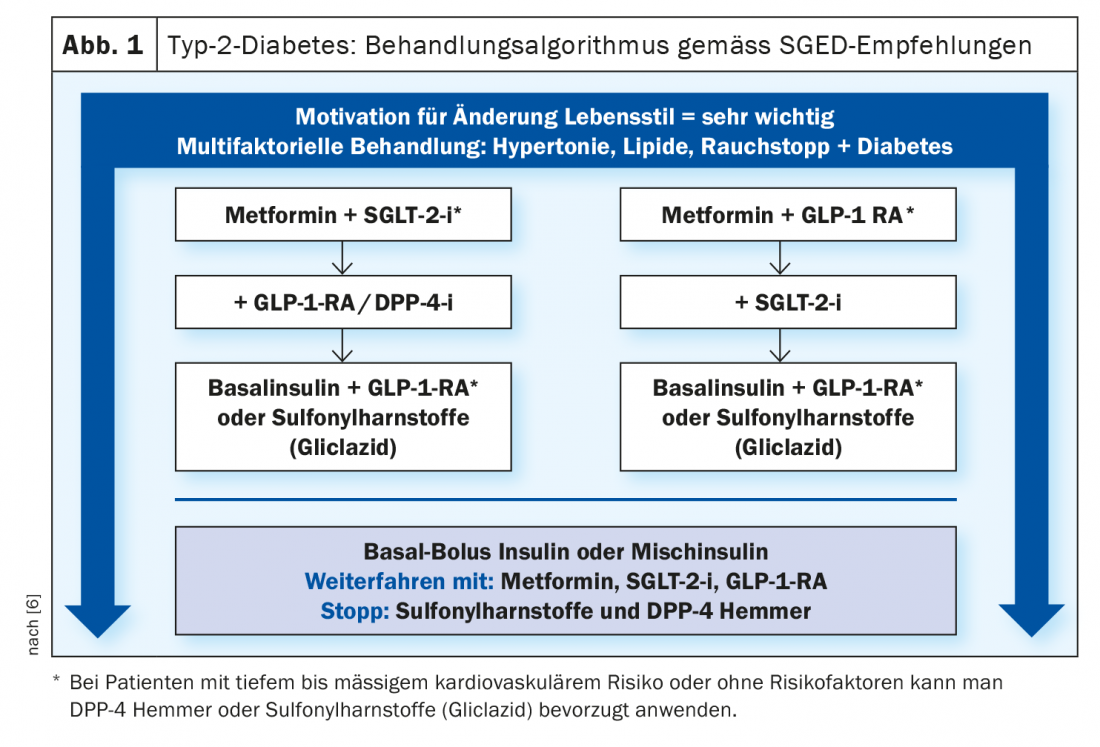

Lifestyle changes (diet, physical activity, patient education) are an important component of modern type 2 diabetes therapy, but as stand-alone measures often do not achieve the goal. The pharmacotherapeutic approach recommended by current guidelines prioritizes metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, and GLP-1 analogues. In clinical practice, the question now arises: How to proceed in selecting the appropriate drug therapy? Metformin is still considered the first choice, although it is now believed that early combination with an SGLT-2 inhibitor and/or a GLP-1 receptor agonist helps to lower glycemic load and reduce microvascular and macrovascular sequelae. Metformin (Glucophage® and generics) [2] reduces blood glucose levels in a dose-dependent manner after oral administration in diabetics as a result of inhibition of glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in the liver and leads to improved glucose utilization in peripheral tissues. Although metformin did not show a significant reduction in cardiovascular events in a recently published meta-analysis, it remains the preferred first-line drug because all modern studies of cardiovascular outcomes are based on therapy with metformin [3,4]. According to SGED recommendations, metformin can be used at reduced doses up to an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 ml/min. However, it should not be re-prescribed at an eGFR <45 ml/min, and existing doses should be halved [6].

The new substance classes protect the heart and kidney

Studies show that the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors and/or GLP-1 receptor agonists can significantly reduce cardiovascular events (box) . In particular, SGLT-2 inhibitors should be started early in chronic heart failure or renal insufficiency. “The SGLT-2 inhibitors reduce albuminuria, stabilize eGFR, and reduce progression of renal failure,” Prof. Brändle explains.

Even patients without diabetes with cardiac and/or renal insufficiency benefit from the cardio- and nephroprotective effects of this substance class. If metformin is contraindicated or intolerable, the use of an SGLT-2 inhibitor or GLP-1 analogue can be considered at the outset, especially in cases of increased cardiovascular risk (Fig. 1) . Possible alternatives are DPP-4 inhibitors or sulfonylureas (gliclazide retard) [5]. GLP-1-RA, like the endogenous incretin GLP-1, bind to GLP-1 receptors and lead to increased insulin secretion and inhibition of glucagon release. In addition, they inhibit appetite and are therefore particularly suitable for overweight diabetic patients.

Which patients need insulin treatment?

In addition to cardiovascular disease and renal insufficiency/ nephropathy, the presence of insulin deficiency is the third important criterion for the indication of therapy according to SGED recommendations. Insulin treatment should be considered from an HbA1c of 8.5-9% [5]. That glycemic control (HbA1c 7-7.5%) is still of long-term relevance in both newly diagnosed and long-term diabetic patients with complications is shown, among others, by an analysis of Swedish registry data. In it, cardiovascular mortality was calculated as a function of glycemic control (HbA1c) and age. There was a positive correlation between the level of HbA1c values (<6.9% to >9.7%) and cardiovascular risk in the age groups studied (<55- to >75-year-olds). This was highest for the group of diabetes patients younger than 55 years [7].

Congress: FomF Family Doctor Training Days

Literature:

- Brändle M: Diabetes mellitus type 2 – challenges in daily practice, Hausarzt Fortbildungstage St. Gallen, 11.03.2021

- Drug Information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch, (last accessed 07/19/2021).

- Griffin SJ, Leaver JK, Irving G: Diabetologia 2017; 60(9): 1620-1629.

- Schneider L, Lehmann R: Swiss Med Forum 2021; 21(1516): 251-256.

- Kohler S, Beise U, Huber F: Diabetes mellitus, MediX, Last modified 02/2021 Diabetes mellitus, www.medix.ch (last accessed 07/19/2021).

- Lehmann R, et al: Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology (SGED/SSED) Recommendations for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus 2020, www.sgedssed.ch (last accessed 07/19/2021).

- Tancredi M, et al. NEJM 2015; 373: 1720-1732.

- Zinman B, et al: NEJM 2015; 373(22): 2117-2128.

- Neal B, et al: NEJM 2017; 377(7): 644-657.

- Wiviott SD, et al: NEJM 2019; 380(4): 347-357.

- McMurray JJV, et al: NEJM 2019; 381(21): 1995-2008.

- Cannon CP, et al: NEJM 2020; 383(15): 1425-1435.

- Wanner C, et al: NEJM 2016; 375(4): 323-334.

- Perkovic V, et al: NEJM 2019; 380(24): 2295-2306.

- Mann JFE, et al: NEJM 2017; 377(9): 839-848.

- Marso SP, et al: NEJM 2016; 375(4): 311-322.

- Marso SP, et al: NEJM 2016; 375(19): 1834-1844.

- Husain M, et al: NEJM 2019; 381(9): 841-851.

- Pratley R, et al: Lancet 2019; 394(10192): 39-50.

- Gerstein HC, et al: Lancet 2019; 394(10193): 121-130.

- Gerstein HC, et al: Lancet 2019; 394(10193): 131-138.

- Holman RR, al: NEJM 2017; 377(13): 1228-1239.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(8): 34-35 (published 8/18-21, ahead of print).