Back pain requires interdisciplinary approaches to solutions, this is also a conclusion of the Back Report 2020 published by the Swiss Rheumatism League. A multimodal coping strategy of lifestyle modification and pain-relieving medications promises the best efficacy. If “red flags” are present, further clarifications should be made.

The Back Report 2020 shows that back pain is widespread in the Swiss population and is associated with significant health, social and financial consequences. 88% of respondents reported having suffered from back pain at some point in their lives [1]. If the symptoms last less than 4 weeks, they are referred to as acute back pain, if they last 4-12 weeks, they are referred to as subacute back pain, and if they last more than 12 weeks, they are referred to as chronic back pain [2]. Adequate measures at an early stage can prevent or mitigate a chronicizing course [1].

Identify risk factors

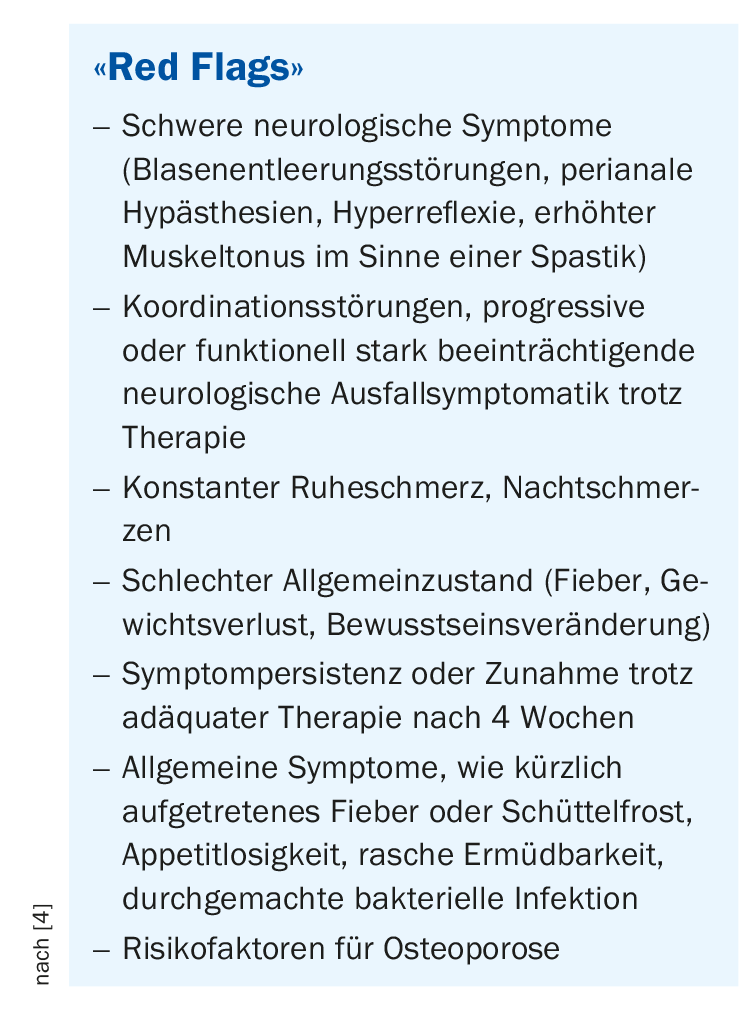

The most important risk factors include lack of exercise, poor posture, obesity and psychological stress. About half of the people surveyed in the Back Report said they spend six hours or more per day in sedentary work. In particular, long periods of uninterrupted sitting increase the risk of back pain. However, psychosocial factors also play a significant role in chronification [1,3,4]. Corresponding warnings are among the “yellow flags” and should be recorded at an early stage. A balance between activity and rest, as well as good stress management, are important factors in all phases of back pain prevention and treatment and should be addressed. “Red flags” are warning signals indicating fracture, tumor, infection or radiculopathy and should be investigated further(box) [4].

Multimodal treatment approach has proven successful

As with chronic back pain, self-management is also an important measure for acute back pain, emphasizes Matthias Seidel, MD, Head of Rheumatology, Biel Hospital Center [2]. Promoting flexibility and strengthening exercises has been shown to have a preventive effect [5]. Ergonomic factors in the workplace should also be addressed. A combined treatment strategy consisting of lifestyle modification and drug intervention promises the best effect. Among pharmacotherapeutic measures, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often, but not always, helpful, explains Dr. Seidel [2].

Targeted use of pain-relieving drugs

Specific recommendations for drug therapy of pain according to the guideline are as follows [4]:

- Classical NSAIDs for a period of 2-4 weeks, when pain-free the medication should be discontinued. In addition to ibuprofen 400-600 mg (4×/d), naproxen 500 mg (2×/d) and diclofenac 50-75 mg (2×/d) are suitable for this indication [6,7].

- Alternatively, the use of COX-2 inhibitors can be investigated [4]. Unlike traditional NSAIDs, these selectively inhibit inducible cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) rather than constitutive COX-1, and efficacy is comparable [6].

- In case of contraindications or intolerance to other non-opioid analgesics, metamizole can be substituted, and the duration of treatment should be as short as possible [6].

- Muscle relaxants have been shown to be effective for muscle-related back pain, and the duration of treatment should not exceed 2 weeks [8]. Muscle relaxants with a central depressant effect that are approved for pain therapy in Switzerland include methocarbamol and tizanidine.

- Opioids are another alternative in cases of non-response or contraindications to NSAIDs, although it is particularly important here to limit the duration of use to the shortest possible period (maximum 2-3 weeks, use sustained-release preparations if possible) [6].

For all active substances mentioned, patients should be informed about possible side effects and specific contraindications should be observed. If preparations are considered for “off-label” use, this should be critically reviewed on a case-by-case basis [6,9].

Literature:

- Rheumaliga Schweiz: Rückenreport Schweiz 2020, www.rheumaliga.ch, (last accessed 22.02.2021)

- Seidel M: The back pain in focus – differential diagnoses and therapeutic strategies. PD Matthias Seidel, MD, FomF General and Internal Medicine, June 27, 2020.

- Luomajoki H: physiopraxis 2016; 14(05): 46-47.

- Sajdl H & Brüne B: mediX: Guideline. Back discomfort. September 2018, www.medix.ch (last accessed Feb. 22, 2021).

- Wheeler S, et al: Evaluation of low back pain in adults. UpToDate 2018.

- BÄK, KBV, AWMF: Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Nicht-spezifischer Kreuzschmerz. Aufl.; 2017.

- Choi BK, et al: The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2010: CD006555.

- Van Tulder MW, et al: The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 200 3: CD004252.

- Machado GC, et al: BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2015; 350: h1225.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(3): 22