Blistering autoimmune dermatoses (BAIDs) are a group of rare, potentially life-threatening diseases that manifest clinically as lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, but which, contrary to intuition, may not always be accompanied by blistering. The skin and mucous membrane changes are triggered by an autoantibody-mediated reaction of the immune system to structural proteins of the skin.

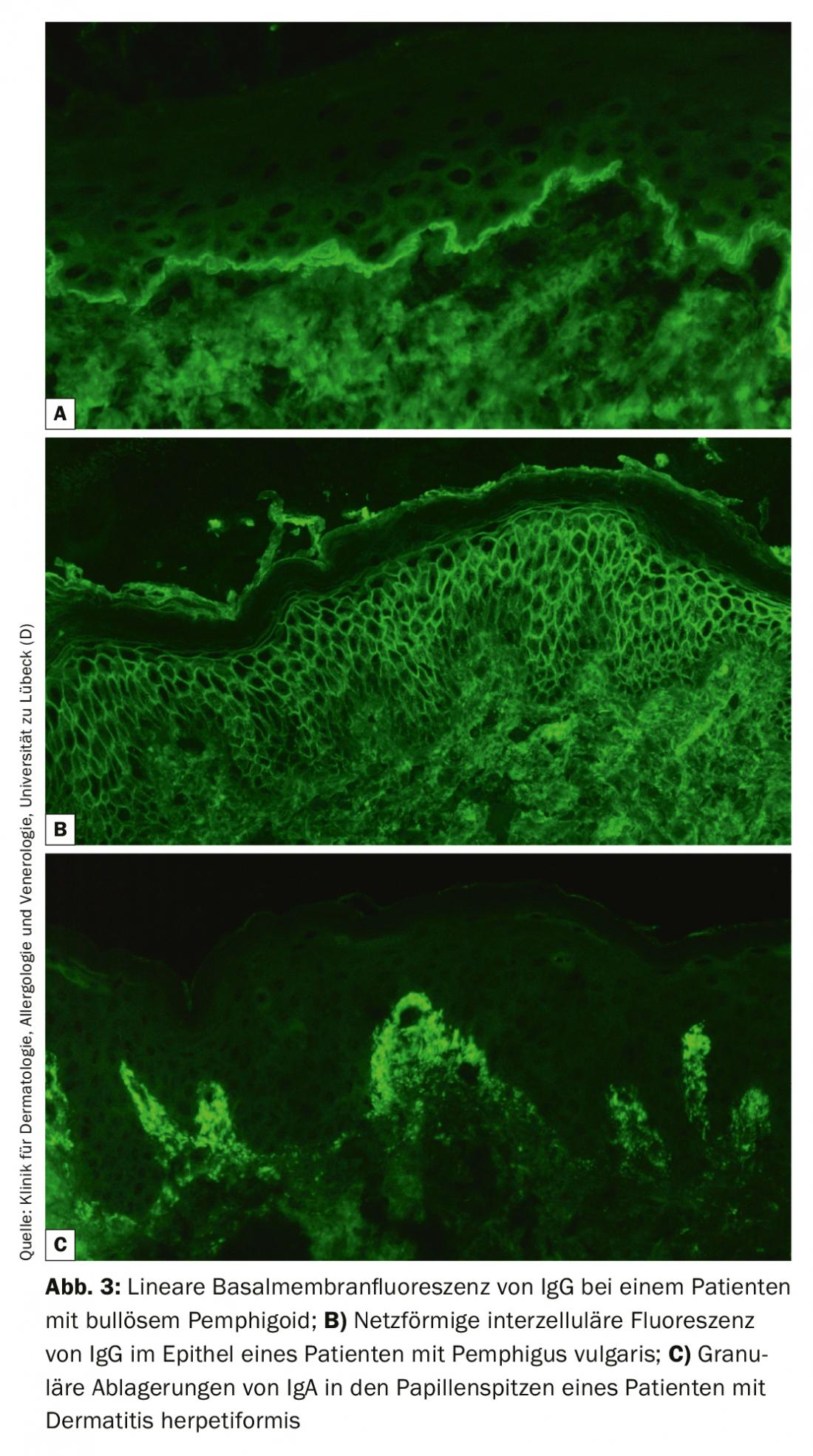

Blistering autoimmune dermatoses (BAIDs) are a group of rare, potentially life-threatening diseases that manifest clinically as lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, but which, contrary to intuition, may not always be accompanied by blistering. The skin and mucosal changes are triggered by an autoantibody (AAK)-mediated response of the immune system to structural proteins of the skin that cause the integrity of the epithelium itself (desmosomes) or that of the epithelial anchorage to the underlying connective tissue of the skin or mucosa. The former are grouped as pemphigus diseases and the latter as pemphigoid diseases (Table 1) [1,2]. Dermatitis herpetiformis, in which antibodies against transglutaminase 2 and 3 are formed and which is always accompanied by celiac disease, must be distinguished from this [3].

The target antigen of the autoantibodies significantly influences the pathogenesis and thus the clinical appearance of BAID, serves by its determination for the exact diagnosis and has a decisive influence on the prognosis and therapy to be applied. In the following, we will mainly consider the recognition and differentiation of pemphigus and pemphigoid diseases and the diagnostic steps. More in-depth information is provided by the current guidelines [4,5] (EADV guideline pemphigus and DH) as well as the regularly published scientific research articles and reviews.

Epidemiology: Except for pemphigoid gestationis, all BAID can in principle occur at any age, but there is a typical age distribution of the individual diseases. While linear IgA dermatosis is most common in children and adolescents, people with bullous pemphigoid usually do not develop the disease until after the age of 75, and patients with pemphigus are again one to two decades younger on average [6,7]. Geographically, bullous pemphigoid dominates in Northern and Central Europe and North America with an incidence of approximately 20/million population/year. In southern Europe, Israel, and Iran, pemphigus is the most common BAID with an annual incidence of 5-15 million/inhabitant [1]. In Switzerland, the incidence of bullous pemphigoid was found to be 12.1/million/year and pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus 0.6/million/year in 2001/2002 [8]. All other BAID occur even less frequently than pemphigus.

Autoantigens and clinical presentation

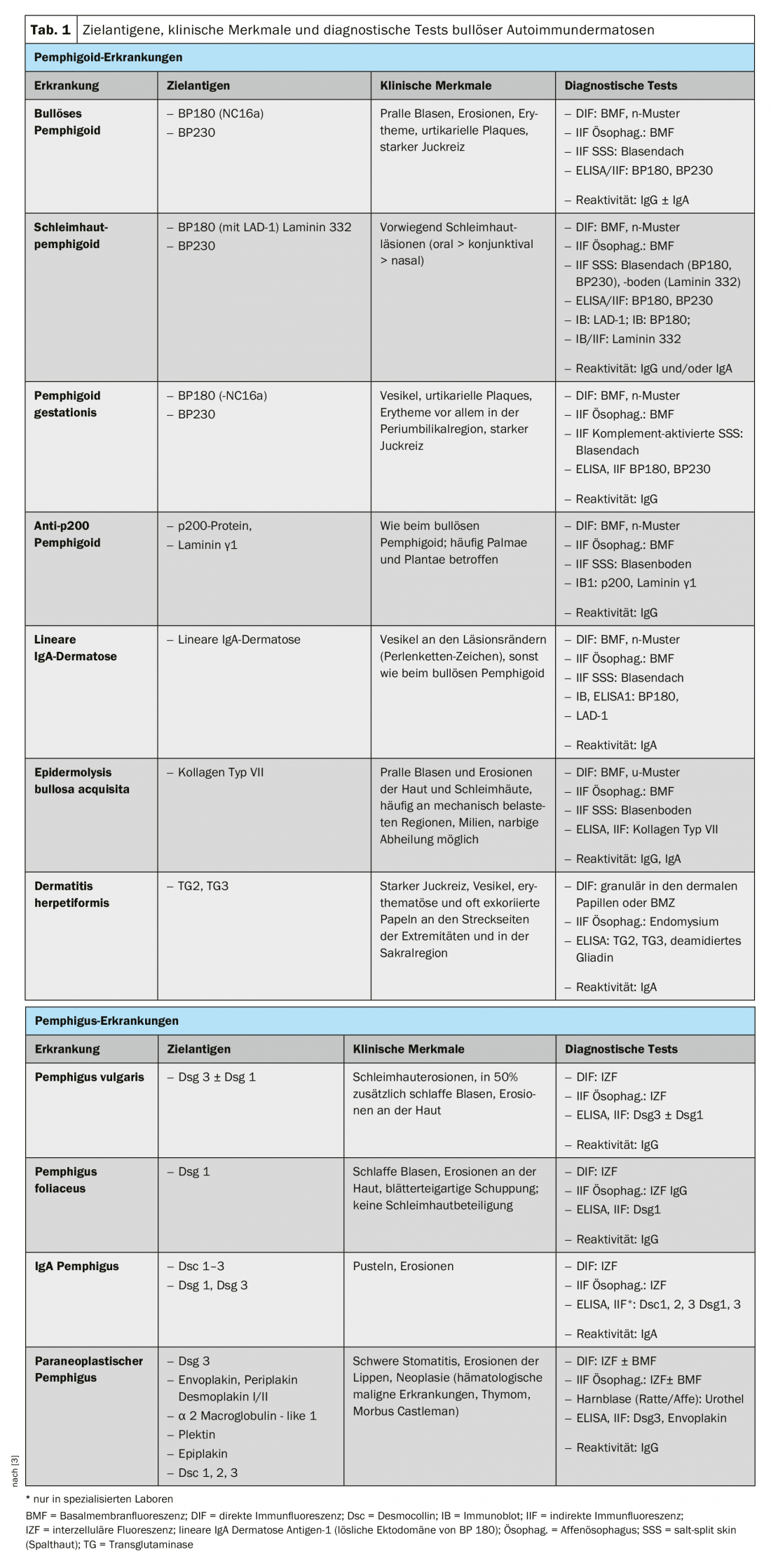

To understand the clinic of BAID, it is first worthwhile to look at the distribution of target antigens within the skin and mucosa (Fig. 1) . The target antigens of the pemphigoid group ensure the anchoring of the epithelium to the basement membrane and the underlying connective tissue. This area is also called the dermo-epidermal junction zone. When the autoantibodies bind to these structural proteins, a complex inflammatory response occurs with local activation of the complement system, infiltration of eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes into the upper dermis, and subsequent release of reactive oxygen species and proteases by these cells, ultimately destroying the dermo-epidermal junction zone [9]. This results in subepidermal cleft formation and clinically typical bulging (serous/hemorrhagic) blisters (Fig. 2C). Mechanical irritation leads to erosion of the skin and, in some cases, the mucous membranes. The autoantibodies of bullous pemphigoid bind to BP180 (type XVII collagen), mainly to the BP180 NC16A domain, and in half of the patients also to BP230 (Table 1) . 20% of bullous pemphigoid cases progress without blistering with a variety of clinical pictures including urticarial erythema, excoriated papules and eczema [10]. Practically always there is a pronounced itching. Of great clinical importance is the association of BP with various neurological diseases in 30-50% of patients, as well as with diabetes mellitus and hematologic malignancies [2,11]. It has recently become clear that certain oral antidiabetic drugs, the dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, particularly vildagliptin, can trigger BP, so these drugs should not be used in BP [12].

The NC16A domain of BP180 is also the immunodominant region in pemphigoid gestationis, a BAID that occurs predominantly in the second half of pregnancy and generally resolves 5-6 months after delivery. However, recurrences are common with new pregnancies. Linear IgA dermatosis has IgA antibodies to more C-terminal epitopes of BP180.

In mucous membrane pemphigoid, the mucous membranes are predominantly affected, including especially the oral cavity and the conjunctiva, as well as the mucous membranes of the nose, pharynx, pharynx , trachea, esophagus, and genitals (Fig. 2D) . Except in the mouth, scarring regularly occurs. Complications of this scarring include possible blindness and airway obstruction. In mucosal pemphigoid, the autoantibodies are directed against C-terminal epitopes of BP180 or laminin 332 (Table 1) . Anti-p200 pemphigoid is clinically similar to BP, but the autoantibodies are directed against a 200 kDa protein of the dermo-epidermal junction. In the vast majority of patients, autoantibodies also react with laminin γ1 [13]. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is defined by antibodies to type VII collagen and manifests clinically in two main forms, the inflammatory variant resembling a BP or mucous membrane pemphigoid, or the classic mechano-bullous variant with blisters, erosions, and scarring on exposed body sites such as the back of the hand [14].

The target antigens of the pemphigus group, the desmosomal cadherins desmoglein 1 and 3 (Dsg 1, 3), are formed by the epithelial cells to bind tightly together (Fig. 1). If they are attacked, the epithelial cell association dissolves (acantholysis). Clinically, this can be demonstrated by using shear forces to superficially detach perilesional, healthy-appearing skin (Nikolski phenomenon). However, since the stability of a blister depends on the degree of intraepithelial integrity and this is directly damaged, in pemphigus one observes flaccid blisters that rupture rapidly, so that erosions usually form. Dsg 1, the target antigen in pemphigus foliaceus (PF), is mainly produced in the upper epidermal layers of the skin and mucosa, and Dsg 3 is not expressed there in the skin, so that PF manifests itself by erosions, crusts, and a fine lamellar scaling on the skin, but the mucous membranes are always free (Dsg compensation hypothesis, Fig. 2A) [1,15]. Dsg 3, the target antigen in pemphigus vulgaris (PV), is expressed primarily in the lower layers of the epithelium; however, at these sites, Dsg1 is found only in the epithelial mucosa but not in the skin. Thus, in PV, the presence of exclusively anti-Dsg3 antibodies results in exclusively mucosal erosions (Fig. 2B), which are often painful, may interfere with food intake, and may lead to weight loss. In mucocutaneous PV with antibodies to Dsg3 and Dsg1, erosions and flaccid blisters develop on the skin in addition to mucosal lesions. Unlike pemphigoid disorders, no inflammatory response is necessary for blister formation; binding of anti-Dsg antibodies to epithelial cells alone is sufficient to trigger acantholysis. Here, steric hindrance of desmosomal interaction by binding of autoantibodies, altered expression of Dsg molecules on the cell surface, and complex signal transduction-mediated remodeling of the cytoskeleton of epithelial cells play a crucial role [15]. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is always associated with a neoplasm, most commonly a thymoma or hematologic malignancy, and is clinically characterized by marked stomatitis and frequent lip involvement. In addition to Dsg 3, the autoantibodies are directed against plakin family proteins (including envoplakin, periplakin, BP230) and α2-macroglobulin-like 1 [1].

Diagnostics

Because the clinical presentation of BAID is so varied and not always clearly attributable to a specific BAID, differential diagnosis should exclude infectious causes (impetigo, bullous erysipelas, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, herpes virus infections), hereditary diseases (porphyria, hereditary epidermolysis bullosa), as well as drug exanthema and chemical and physical noxae [4]. In the case of involvement of the oral cavity, the differential diagnosis should be primarily a lichen ruber mucosae; in the case of ocular involvement, an infectious, allergic or irritative genesis should be considered. Especially in cases of ocular involvement, mucous membrane pemphigoid should be considered early, as this is the only way to therapeutically prevent irreversible scarring. Figure 2 and Table 1 summarize the clinical characteristics.

In the diagnosis of BAID, direct immunofluorescence (IF) of a perilesional biopsy and detection of circulating autoantibodies by indirect IF, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and immunoblots are essential in addition to clinical findings [4].

Accurate diagnosis of each BAID is both of prognostic importance and relevant to therapy. Thus, paraneoplastic pemphigus is virtually always associated with malignancy and anti-laminin-332 mucinous pemphigoid is associated with malignancy in 25-30% of cases, and a tumor search is indicated in these patients [1,16,17]. Pemphigus disease, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and mucosal pemphigoid with ocular, laryngeal, or tracheal involvement require intensive immunosuppressive therapy, whereas anti-p200 pemphigoid, linear IgA dermatoses, and dermatitis herpetiformis usually require only mild immunosuppression or a gluten-free diet.

Direct immunofluorescence

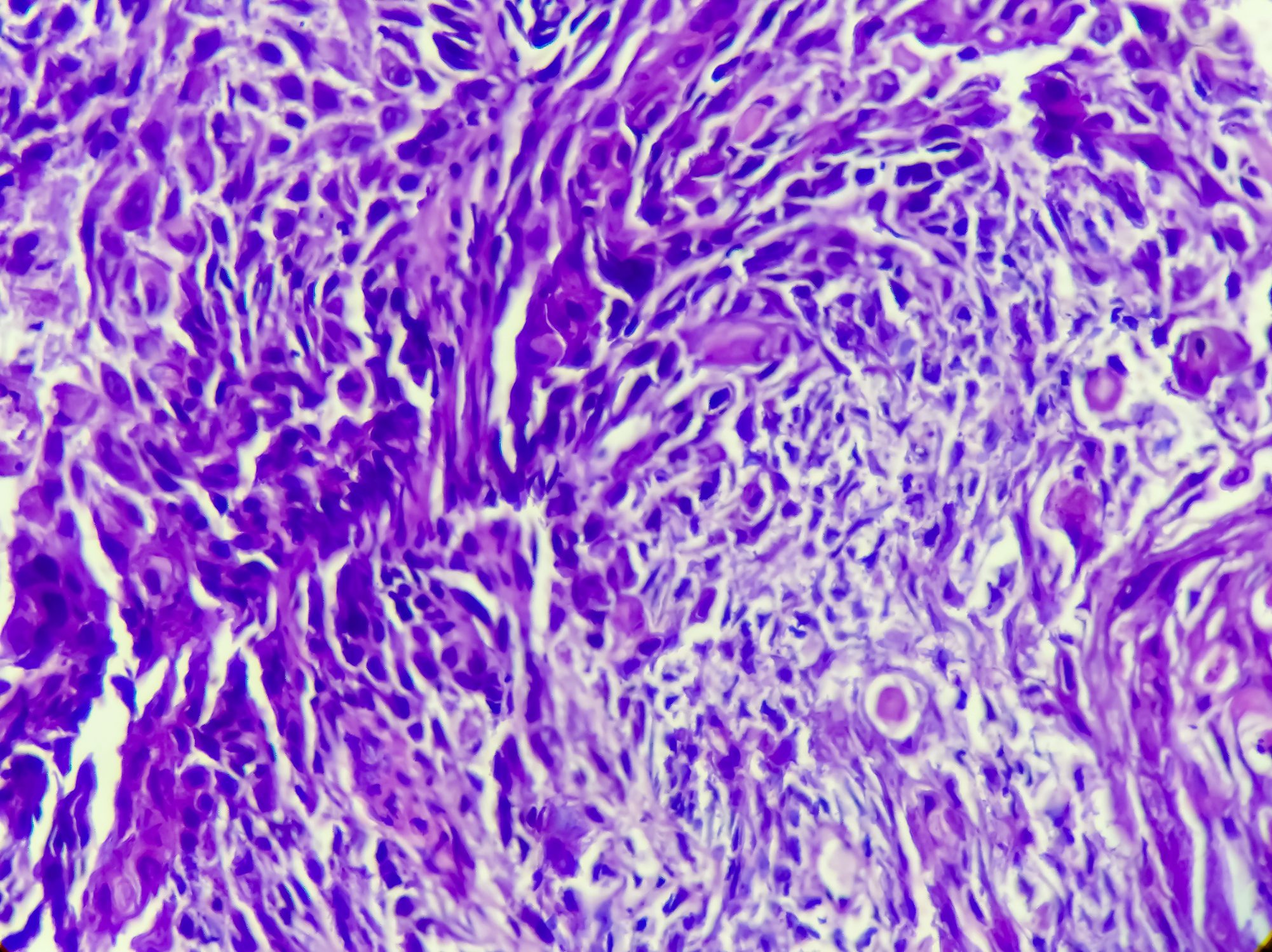

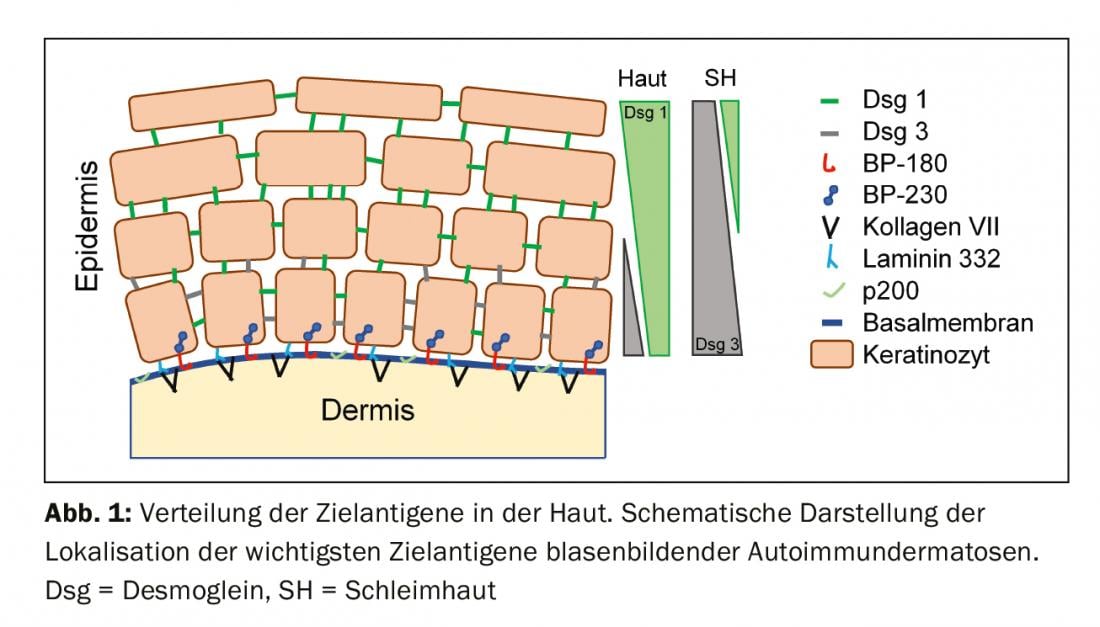

Direct IF of a perilesional biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard of BAID with a specificity of 98% and sensitivity of 80-90% [4]. The sample biopsy must be frozen immediately after collection or stored in 0.9% NaCl or Michels medium and processed within 72 hours. Then, tissue-bound autoantibodies (immunoglobulin [Ig] G, A, and M) and complement factor C3 are visualized on frozen sections using a fluorescently labeled antibody. Recognition of a typical fluorescence pattern basically allows a reliable diagnosis of pemphigus (epithelial intercellular fluorescence/net pattern), pemphigoid (linear fluorescence along the basement membrane) and dermatitis herpetiformis (granular IgA deposits in the papillary tips or along the basement membrane, Fig. 3). In addition, a lesional biopsy should be taken to perform a histologic examination; this serves to diagnose other diseases, especially if direct IF and serology are negative.

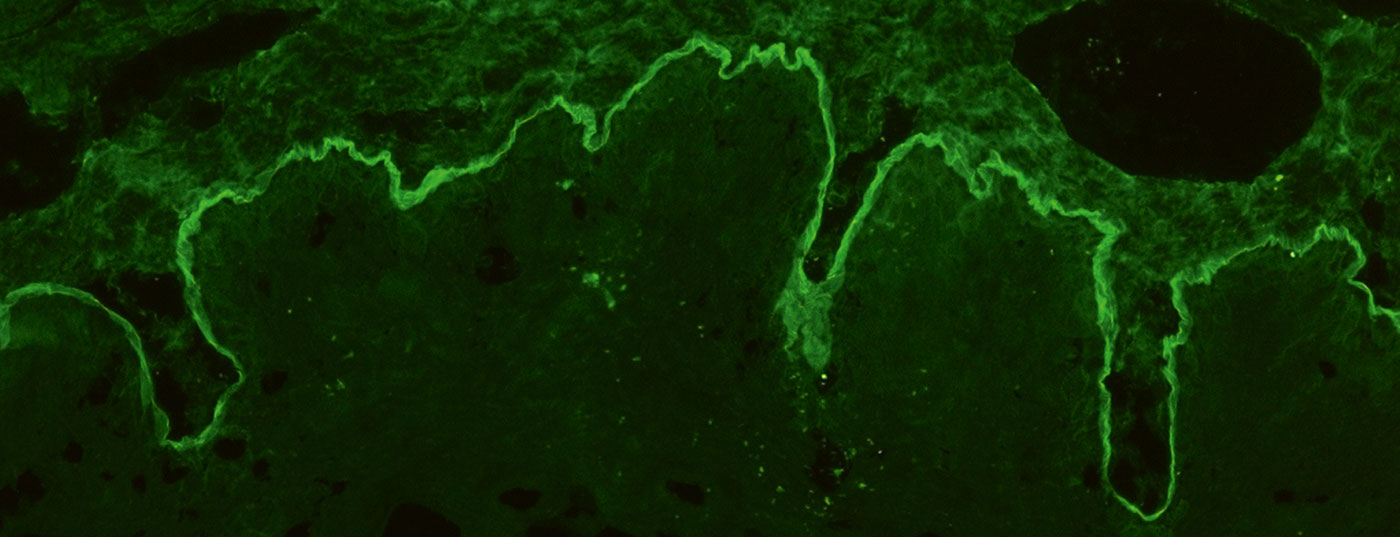

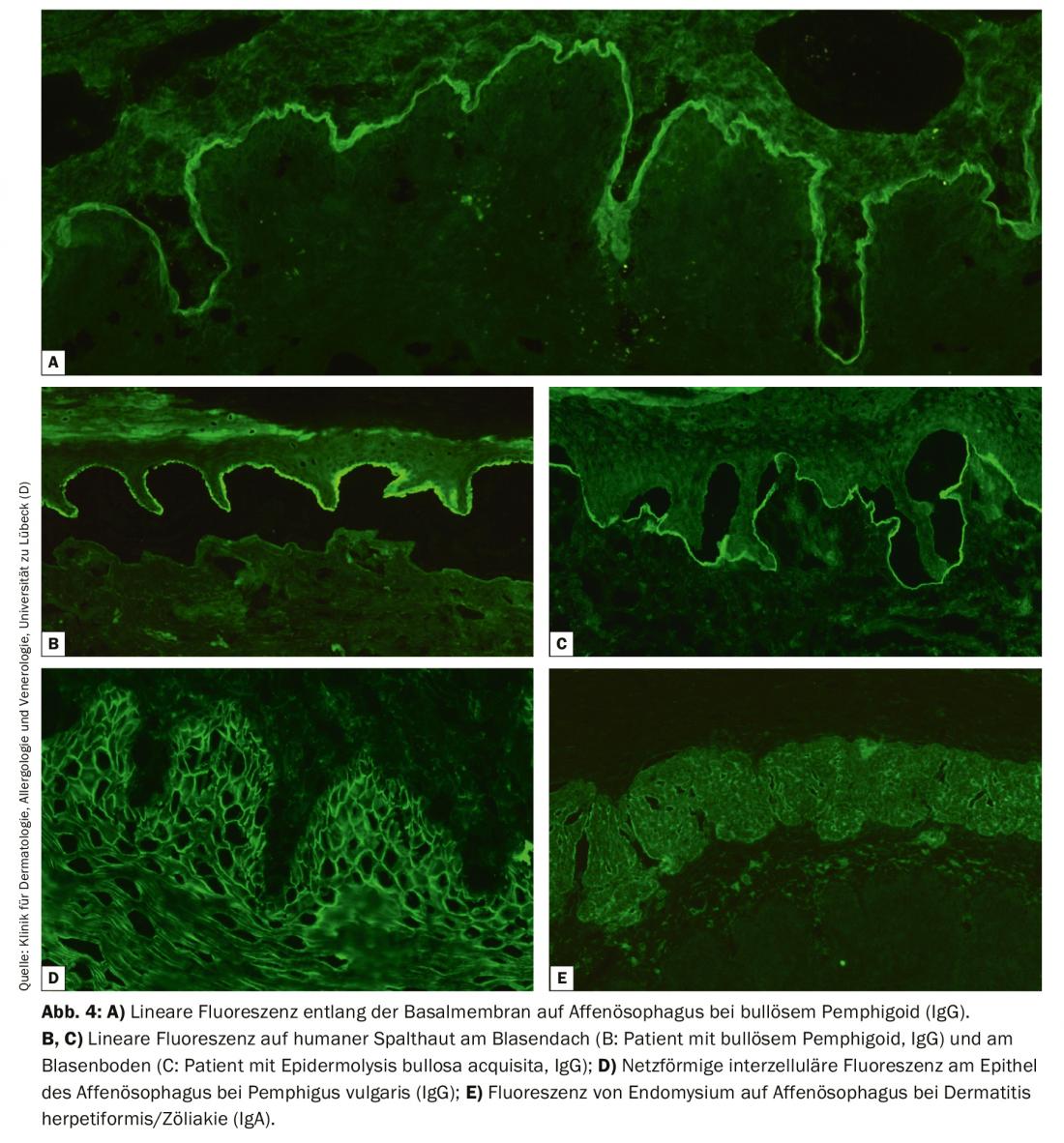

Indirect immunofluorescence on organ substrates.

For indirect IF, primate esophagus is usually used and with NaCl lsg. human skin split at the basement membrane, so-called split skin, is used for the detection of serum autoantibodies in BAID. In esophageal section, autoantibodies can be detected along the basement membrane in pemphigoid diseases (Fig. 4A), in the pemphigus diseases intercellularly at the epithelium (Fig. 4D) and in dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac disease against endomysium (IgA only, Fig. 4E). In split skin, serum autoantibodies of pemphigoid diseases bind either in the roof of the artificially created bubble (in BP, anti-BP180 mucosal pemphigoid, pemphigoid gestationis, linear IgA dermatosis, Fig. 4B) or in the blister floor (in anti-p200 pemphigoid, anti-laminin 332 mucosal pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, Fig. 4C). Again, IgG and IgA deposits are sought, the latter being typical of linear IgA dermatosis, for example. Less frequently indicated is monkey/rat bladder testing in paraneoplastic pemphigus or complement fixation testing on split skin in suspected pemphigoid gestationis.

Indirect IF on the above-mentioned organ substrates is used as a screening test. Depending on the result, antigen-specific tests, ELISA, indirect IF, immunoblots or immunoprecipitation may then be performed, if necessary, taking into account the direct IF. With the development of antigen-specific tests, mostly using the immunodominant recombinant forms of autoantigens, the diagnosis can now be made serologically in 80-90% of BAID patients [18–20].

ELISA

Very sensitive and specific commercial ELISAs are available for the major target antigens, Dsg1, Dsg3, Envoplakin, BP180 NC16A, BP230 and type VII collagen [3]. For antibodies against Dsg1, BP180 NC16A, type VII collagen and, somewhat less pronounced, for Dsg3, serum levels have been shown to correlate well with clinical activity on skin and mucous membranes of patients with pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, so that ELISA can also be used in the course of disease to monitor disease activity. This is particularly relevant for patients in clinical remission, in whom it must be decided to what extent immunosuppressive therapy can be further reduced.

Multivariate test systems: Multivariate test systems were developed in order to investigate different autoantibody specificities in one step and to save time compared to the multistep procedure described above. One is an ELISA in which the recombinant proteins were placed on a single ELISA plate [18], the other is based on Biochip® technology. Here, up to 12 substrates measuring only about 1×1 mm are compiled in an incubation field on a normal laboratory slide and autoantibody binding is visualized by indirect IF. In addition to organ substrates such as primate esophagus and human split skin, recombinant BP180 NC16A and Dsg1, Dsg3, BP230, laminin 332, type VII collagen expressed on the cell surface of HEK293 cells are also available [19].

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation

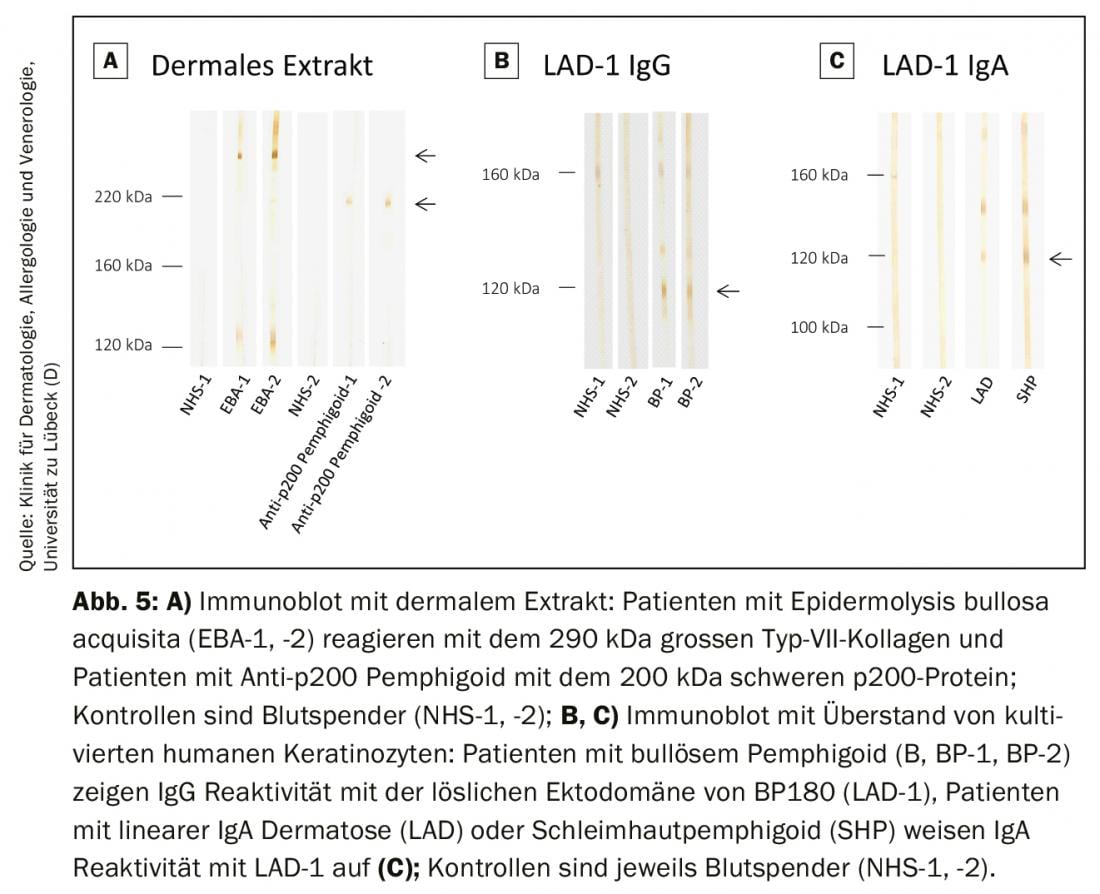

In specialized laboratories, these methods are offered as in-house procedures to detect those autoantibody specificities not yet covered by commercial test systems. This includes the detection of autoantibodies against the complete type VII collagen molecule as well as the p200 protein (Fig. 5A) and the detection of IgG and IgA antibodies against the ectodomain of BP180, which is the immunodominant region in mucinous pemphigoid and linear IgA dermatoses. (Fig. 5B and C). Antibodies against periplakin, desmoplakin I/II, plectin, epiplakin, desmocollins, and α2-macroglobulin-like 1 in paraneoplastic pemphigus can be visualized in various immunoblot and immunoprecipitation analyses. In Germany, the German Accreditation Body (DAkkS) offers the possibility of external auditing of these in-house procedures to ensure the highest possible standard of diagnosis. The autoimmune laboratory of the University Dermatological Clinic Lübeck offers these procedures (DAkkS D-ML-13069-06-00; www.uksh.de/dermatologie-luebeck).

Special constellations of findings

If the findings are unclear, re-taking of a perilesional sample biopsy for direct IF is recommended [4]. In mucous membrane pemphigoid, it was shown that in 16% of patients the diagnosis could only be confirmed by a second direct IF [21]. Direct IF is particularly important in mucous membrane pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, as no circulating autoantibodies can be detected in 50% of cases.

In the vast majority of BAID patients, the diagnosis can nowadays already be made serologically using commercial test systems if the clinical picture is compatible [18,19]. We also recommend serologic testing as an initial screening test when a sample biopsy should initially be avoided, e.g., in children or patients >75 years of age with >6 weeks of persistent pruritus that cannot be explained by another disease.

The current AWMF guideline [5] recommends the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus in the case of

- matching clinical picture and positive direct immunofluorescence

- appropriate clinical picture and reactivity with desmoglein 1 or 3 in ELISA/in transfected cells

- matching clinical picture and histopathology and positive indirect immunofluorescence on monkey esophageal sections.

Diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid in the case of

- matching clinical picture and positive direct IF and reactivity with BP180 and/or BP 230.

- matching clinical picture and positive direct IF and epidermal binding of IgG in indirect IF on split skin

- Clinical picture with bulging blisters and epidermal binding of IgG in indirect IF on split skin or monkey esophageal sections and reactivity with BP180 and/or BP230.

- clinical picture with bulging blisters and matching histopathology and epidermal binding of IgG in indirect IF on split skin

- matching clinical picture and histopathology (subepidermal cleavage) and reactivity with BP180

- clinical picture with bulging bubbles and clear reactivity with BP180 (e.g. >3-fold of the lower detection limit in commercial ELISA)

Summary

Blistering autoimmune dermatoses (BAID) are a group of rare, potentially life-threatening diseases that manifest clinically as lesions on the skin or mucous membranes and may not always be associated with blistering. The skin and mucosal changes are triggered by an autoantibody-mediated response of the immune system to structural proteins of the skin that cause the integrity of the epithelium itself (desmosomes) or that of the epithelial anchorage to the underlying connective tissue of the skin or mucosa. The former are grouped as pemphigus diseases and the latter as pemphigoid diseases. Dermatitis herpetiformis, in which antibodies against transglutaminase 2 and 3 are formed and which is always accompanied by celiac disease, must be distinguished from this. The target antigen of the autoantibodies significantly influences the pathogenesis and thus the clinical appearance of BAID, serves by its determination not only the exact diagnosis, but has a decisive influence on the prognosis and therapy to be applied. The diagnosis of BAID is based on the detection of tissue-bound autoantibodies in the direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional sample biopsy as well as the detection of circulating autoantibodies. Knowing the clinical picture, modern ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence tests based on the immmundominant regions of the target antigens can already serologically diagnose 80-90% of BAID patients. The development of additional standardized sensitive and specific test systems will further facilitate the diagnosis of BAID.

Take-Home Messages

- Bullous autoimmune dermatoses are rare diseases triggered by autoantibodies against structural proteins of the skin.

- By far the most common bullous autoimmune dermatosis in Northern and Central Europe is bullous pemphigoid, which is clinically characterized by advanced age, severe pruritus, bulging blisters, and association with neurologic disease.

- Accurate diagnosis is of prognostic and therapeutic relevance.

- Standardized highly sensitive and specific ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence assays using the immunodominant region of target antigens are available.

- Knowing the clinical picture, serologic tests allow a definite diagnosis in the vast majority of patients; perilesional specimen biopsy for direct immunofluorescence examination remains the diagnostic gold standard.

Acknowledgement

We thank Ingeborg Atefi and Marina Kongsbak-Reim for assistance with fluorescence images and Vanessa Krull for help with immunoblots. The work was supported by structural funding from the Cluster of Excellence 2167/1 Precision Medicine in Chronic Inflammation.

Literature:

- Schmidt E, Kasperkiewicz M, Joly P: Pemphigus. Lancet 2019; 394: 882-894.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D: Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet 2013; 381: 320-332.

- van Beek N, Zillikens D, Schmidt E: Diagnosis of autoimmune bullous diseases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2018; 16: 1077-1091.

- Schmidt E, Goebeler M, Hertl M, et al: S2k guideline for the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2015; 13: 713-727.

- Schmidt E, Sticherling M, Sardy M, et al: S2k guidelines for the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid: 2019 update. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020; 18: 516-526.

- Hübner F, Recke A, Zillikens D, et al: Prevalence and Age Distribution of Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Diseases in Germany. The Journal of investigative dermatology (JEADV) 2016: 136(12): 2495-2498; doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.013.

- Hübner F, König IR, Holtsche MM, et al: Prevalence and age distribution of pemphigus and pemphigoid diseases among paediatric patients in Germany. In: JEADV 2020; doi: 10.1111/jdv.16467.

- Marazza G, Pham HC, Scharer L, et al: Incidence of bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus in Switzerland: a 2-year prospective study. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161: 861-868.

- Sadik CD, Schmidt E: Resolution in bullous pemphigoid. Seminars in immunopathology 2019; 41: 645-654.

- della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortes B, et al: Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol 2012; 167: 1111-1117.

- Schulze F, Neumann K, Recke A, et al: Malignancies in pemphigus and pemphigoid diseases. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 1445-1447.

- Kridin K, Cohen AD: Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV inhibitor-associated bullous pemphigoid: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018.

- Goletz S, Hashimoto T, Zillikens D, Schmidt E: Anti-p200 pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 185-191.

- Vorobyev A, Ludwig RJ, Schmidt E: Clinical features and diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017; 13: 157-169.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, et al: Pemphigus. Nature reviews Disease primers 2017; 3: 17026.

- Egan CA, Lazarova Z, Darling TN, et al: Anti-epiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid and relative risk for cancer. Lancet 2001; 357: 1850-1851.

- Goletz S, Probst C, Komorowski L, et al: A sensitive and specific assay for the serological diagnosis of antilaminin 332 mucous membrane pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 149-156.

- van Beek N, Dahnrich C, Johannsen N, et al: Prospective studies on the routine use of a novel multivariant enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of autoimmune bullous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 889-894 e5.

- van Beek N, Kruger S, Fuhrmann T, et al: Multicenter prospective study on multivariant diagnostics of autoimmune bullous dermatoses using the BIOCHIP(TM) technology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020.

- van Beek N, Rentzsch K, Probst C, et al: Serological diagnosis of autoimmune bullous skin diseases: Prospective comparison of the BIOCHIP mosaic-based indirect immunofluorescence technique with the conventional multi-step single test strategy. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012; 7: 49.

- Shimanovich I, Nitz JM, Zillikens D: Multiple and repeated sampling increases the sensitivity of direct immunofluorescence testing for the diagnosis of mucous membrane pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77: 700-705 e3.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2020; 30(5): 12-19