Impairments in social communication and social interaction, along with the occurrence of restricted, repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities, form the central diagnostic criterion for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Consequently, a differentiated view of peculiarities in communication is of great importance from a diagnostic as well as from an educational and therapeutic perspective.

Based on the results of international studies, approximately 1% of all children and adolescents in Switzerland currently live with an autism spectrum disorder. The historical change in diagnostic terminology from the original diagnoses of “early childhood autism” (Kanner, 1943) and “autistic psychopathy” (Asperger, 1944) to autism spectrum disorder indicates that today we speak of a broad spectrum of manifestations subsumed under one umbrella term. DSM-5 distinguishes between levels of severity in the diagnostic domains of ‘Social Communication’ and ‘Restrictive, Repetitive Behaviors’ when describing an autism spectrum disorder. ICD-11 goes one step further and explicitly formulates six subtypes of autism spectrum disorder, which can be distinguished from each other according to the criteria of intellectual development as well as functional language development.

If one takes a look at the meaning of communication in the ICD-11, it can be stated that all subtypes have in common that “persistent deficits in the ability to initiate and maintain reciprocal social interaction and social communication” are shown on the symptom level. Functional speech can also be characterized by “a mild or absent impairment,” a general “limitation,” or its “absence,” depending on the subtype [1].

On the one hand, impairments or peculiarities in communication are a unifying, always to be considered descriptive feature of children and adolescents with ASD, at the same time we encounter a very heterogeneous group of persons with regard to the different degrees of development of functional language and cognition – here ICD-11 divides into groups “with” or “without” a disorder of intellectual development.

Characteristic features of communication

A first approach to a differentiated description of communicative peculiarities in autism spectrum disorder can be found in the mentioned diagnostic catalogs. DSM-5 describes the following three criteria of impaired social communication and interaction. Abnormalities in social-emotional reciprocity can manifest themselves on a spectrum from a lack of response to address, to decreased sharing of attention and emotion, to a one-sided, monologue-like conversational style. Difficulties in nonverbal communication behavior are found primarily in understanding and using gestures and facial expressions to regulate social interaction. For example, it may be difficult to interpret facial expressions, eye contact, or hand movements correctly or to use them adequately in communicative contexts. Finally, impaired initiation and maintenance of social relationships encompasses a range from a seeming lack of interest in peers to a lack of understanding of social rules to difficulty establishing friendly contacts.

From the perspective of linguistics, the communicative competencies of children and adolescents with ASD are examined not only with regard to the development of functional language and possible formal language aspects (vocabulary, grammar), but also with regard to conspicuousness on the pragmatic-communicative level [2]. The level of pragmatics includes the appropriate embedding of speech acts in their context, the adequate initiation and shaping of conversations, and the understanding of non-literal meanings of language, e.g., in metaphors, idioms, or ambiguities. Limitations in pragmatic-communicative skills can be observed across the autism spectrum and are found at both the expressive and receptive levels of language.

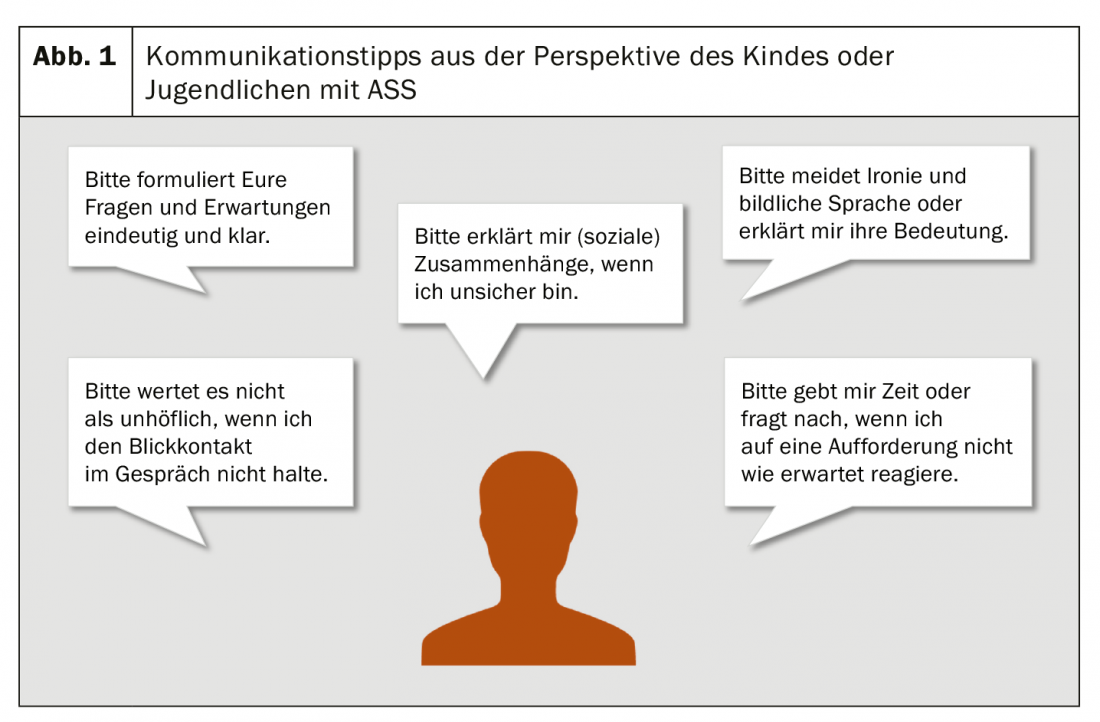

A third approach to the peculiarities of communication can be found in a large number of current publications from an internal perspective. Christine Preissmann, a general practitioner and psychotherapist with her own autism diagnosis, for example, gives a very differentiated insight into her experiences with interpersonal communication in several professional books. Among other things, she describes the very frequent experience of misunderstandings due to her mostly literal interpretation of conversational content [3]. Gee Vero, an artist with an autism diagnosis and mother of a child with ASD, also describes numerous communicative situations that she experienced as challenging when looking back on her school years [4]. In their publications, the authors also formulate suggestions for the design of framework conditions conducive to communication for children and adolescents with ASD as well as tips for the promotion of their communicative competencies. Both approaches follow the goal of supporting participation and individual well-being.

Fundamentals and methods of communication promotion

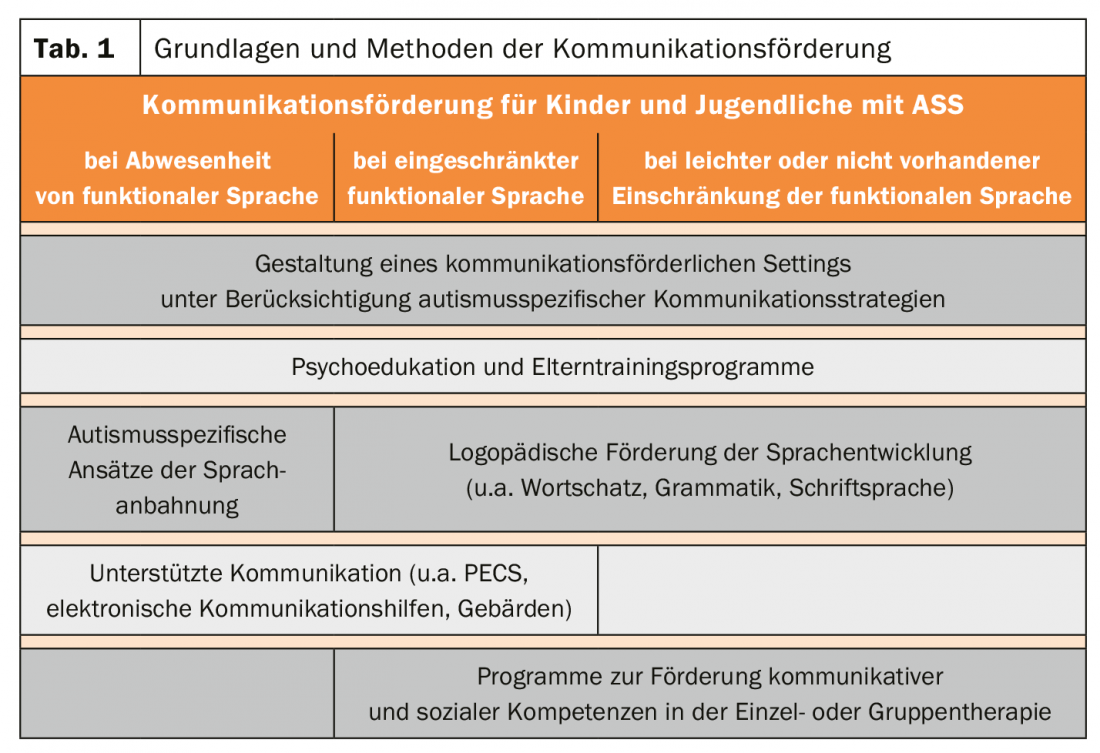

In order to do justice to the great heterogeneity of the communicative prerequisites of children and adolescents with ASD in communication support, an individual selection of the appropriate support approach is necessary. The methods currently encountered in practice, most of which have been scientifically evaluated, are outlined below. The differentiation of autism spectrum disorders according to the degree of existing functional language chosen in ICD-11 serves as an orientation aid for the assignment of the various services, without claiming to pursue a clear distinction (Table 1).

Designing a setting conducive to communication: A foundation of any communication support for children and adolescents with ASD is knowledge about the special thinking and perception of people with ASD. Often very detail-focused thinking can, for example, be associated with not intuitively grasping relevant relationships, especially in social contexts. Problems in changing perspective often make it difficult to understand the thoughts, feelings and intentions of the other person. From these and other findings about autism, numerous concrete suggestions can be derived for designing settings that promote communication, both in therapy and in everyday life. For example, unambiguous language, the avoidance of misleading, ambiguous formulations, and the creation of clear structures and predictability usually make it easier for children and adolescents with ASD to start communicating (Fig. 1).

Psychoeducation and parent training programs: Another key element of communication support that demonstrates a supportive effect for all children and adolescents with ASD is psychoeducation of parents. In recent years, several autism-specific parent training programs have emerged, of which two German-language offerings have been scientifically evaluated and classified as evidence-based. These programs focus on autism education, empowerment, and building parents’ skills for everyday support and encouragement of their children [5,6].

Autism-specific approaches to language initiation: An initial methodological approach for the group of children without functional language is the initiation of language by means of targeted promotion of precursor skills, including attention directing, joint attention, and imitation. In predominantly behavior therapy approaches such as the evidence-based programs of A-FFIP, the Early Start Denver Model, or Applied Behavior Analysis, these skills are taught through play in practice or everyday situations. In addition to these complex programs, individual speech therapy services for autism-specific language acquisition are also available [7].

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC): Often linked to the language acquisition services, AAC services can be used for the same target group as well as for children and adolescents with limited functional language. “Augmentative and Alternative Communication” supplements or replaces spoken language and includes both bodily and electronic and non-electronic communication aids. For children and adolescents with ASD, the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) has been particularly successful as an evidence-based approach, as has the use of communication boards and electronic communication aids, and, in individual cases, learning to sign.

Speech therapy support for language development: Speech therapy support in various areas of language development (including vocabulary, grammar, articulation, acquisition of written language) offers an important opportunity for many children and adolescents with ASD, especially those with mild or non-impaired functional language, to expand communicative skills. Due to the good accessibility of speech therapy in the Swiss educational system, speech therapy is currently one of the most frequently used support services for children and adolescents with ASD.

Programs to promote communicative and social skills: Current programs to promote communicative and social skills primarily address the limitations of pragmatic-communicative skills in children and adolescents with ASD that have already been explained. The current scientific discussion focuses on evidence-based, autism-specific group therapies designed for children and adolescents without significant limitations in functional language and intellectual development. In these programs, a targeted examination of one’s own characteristics and an expansion of competencies in social communication and interaction take place [8]. For individual therapy, there are also increasingly communication-oriented concepts and materials, such as the Social Stories approach or Comic Strip conversations.

Conclusion

The increase in knowledge about the special support needs of children and adolescents with ASD has led to the development of numerous autism-specific approaches to communication support in recent decades. The challenge we face in the present is to provide what is deemed useful from a scientific perspective in a way that meets the needs. The need for action in this regard, despite positive developments in recent years, is also attested by the Federal Council in its report “Autism Spectrum Disorders – Measures for Improving the Diagnosis, Treatment and Support of People with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Switzerland” published in 2018 [9].

Literature:

- ICD-11 – 11th revision of the WHO ICD. www.dimdi.de/dynamic/de/klassifikationen/icd/icd-11/

- Eberhardt M, Snippe K: (2016). Autism and speech therapy. Inventory and perspectives. Logos, 1, 32-39.

- Preissmann C: (2020). Living with Autism. An encouragement. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

- Vero G: (2020). The other child at school. Autism in the Classroom. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Brehm B, Schill JE, Biscaldi M, Fleischhaker C: (2015). FETASS – Freiburg Parent Training for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Berlin: Springer.

- Schlitt S, Berndt K, Freitag CM: (2015). The Frankfurt Autism Parent Training (FAUT-E). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Snippe K: (2015). Autism: pathways to language (2nd ed.). Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner.

- Eckert A, Volkart F: (2016). Social training in the

- Group for children and adolescents with Asperger’s syndrome or high-functioning autism – Literature analysis and practice reflection. Journal of Special Education, 8, 367-380.

- Federal Council (2018). Autism Spectrum Disorders Report. Measures for improving the diagnosis, treatment and support of people with autism spectrum disorders in Switzerland. Bern: Swiss Confederation.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(4): 16-18.