The terms used by patients for various sleep-associated complaints – daytime sleepiness, hypersomnia, fatigue or tiredness (fatigue) – can be understood very inconsistently. They require precise diagnostics to enable targeted therapy.

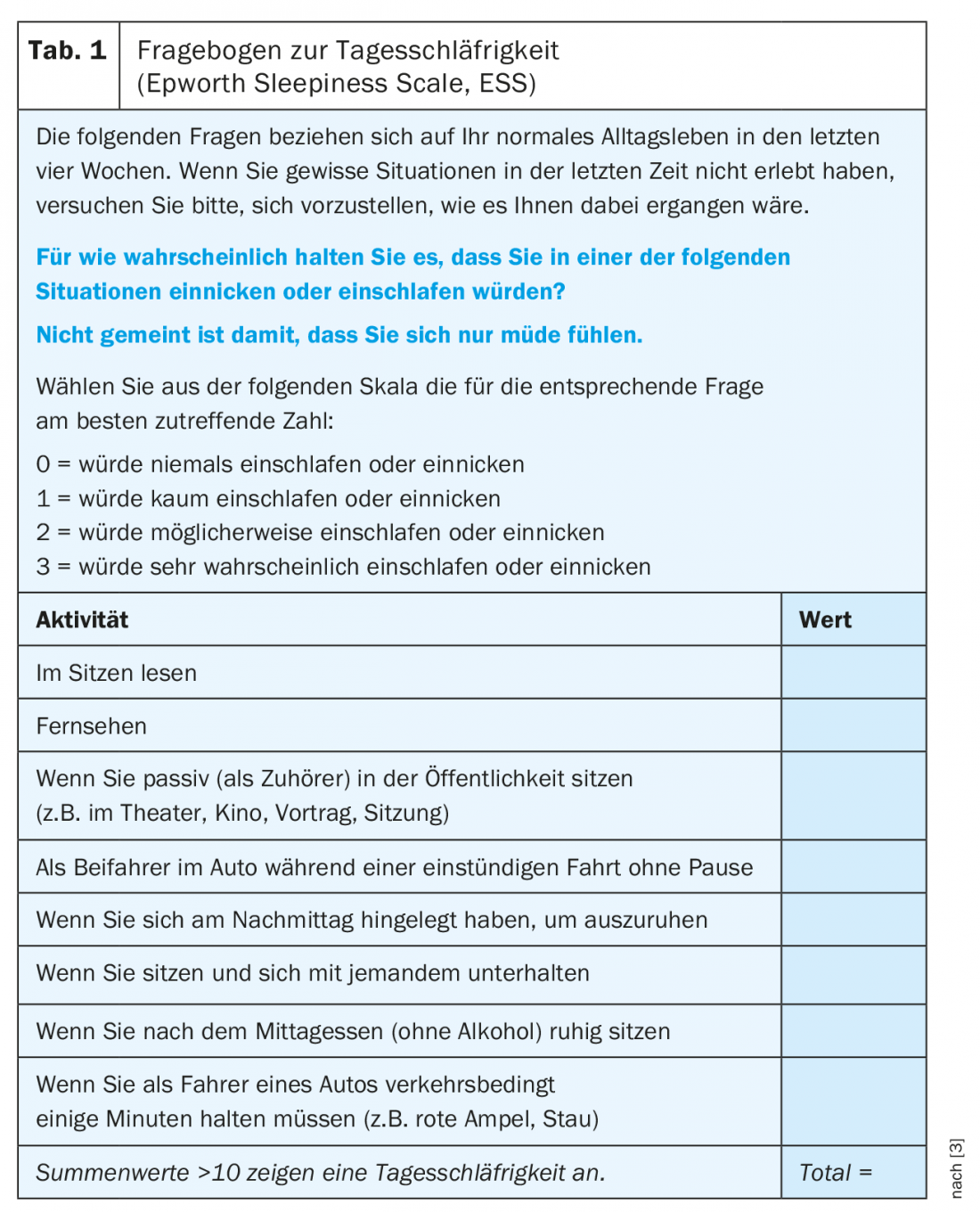

The terms used by patients for various sleep-associated complaints – daytime sleepiness, hypersomnia, fatigue or tiredness (fatigue) – can be understood very inconsistently [1]. The term daytime sleepiness is used to describe increased sleep pressure during the day with increased likelihood of falling asleep in passive or even active situations. In contrast to fatigue, sleepiness improves with physical activity. Daytime sleepiness is indicated by an elevated score (>10/24 points) on the Epworth Questionnaire [3] (Table 1) and by a shortened mean latency to fall asleep (<10 minutes) on the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT).

Hypersomnia is primarily used in the context of specific diagnoses such as idiopathic or nonorganic hypersomnia. At the symptom level, this term represents the prolonged need for sleep per 24 hours. The best method to quantify hypersomnia is polysomnography (PSG) ad libitum, in which the patient is allowed to sleep in as long as he or she can. The number of hours per day that a patient can sleep during the vacations also allows a rough estimate of individual sleep needs.

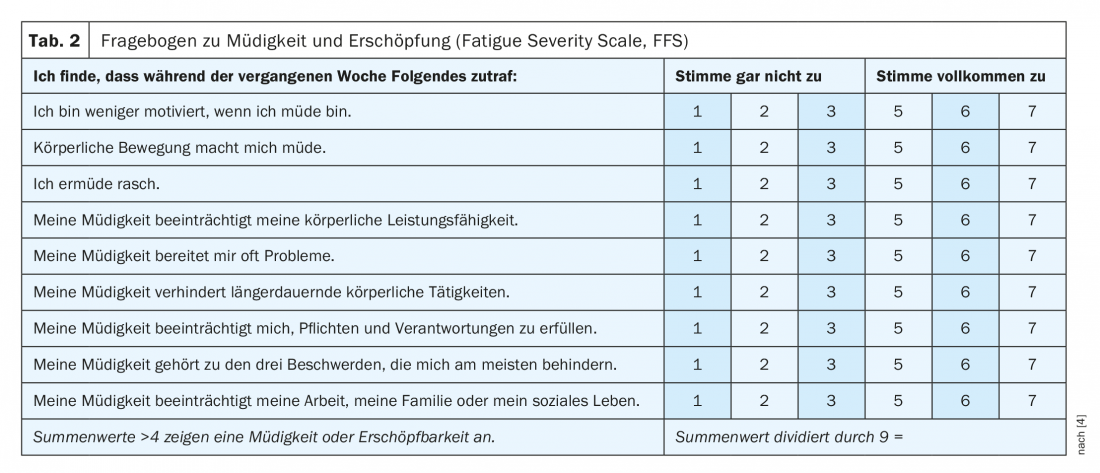

The term fatigue is used for the feeling of a pronounced lack of energy, which increases during both mental and physical activities. The Epworth Sleepiness Score is normal or only slightly elevated, the latency to fall asleep in the MSLT is mostly normal (>10 minutes), but the Fatigue Score [4] (Table 2) is significantly elevated.

Fatigue describes the decrease in performance in the course of mental or physical exertion, usually followed by a greatly prolonged recovery time (>1 hour) in the form of rest, but not necessarily sleep.

What are the causes?

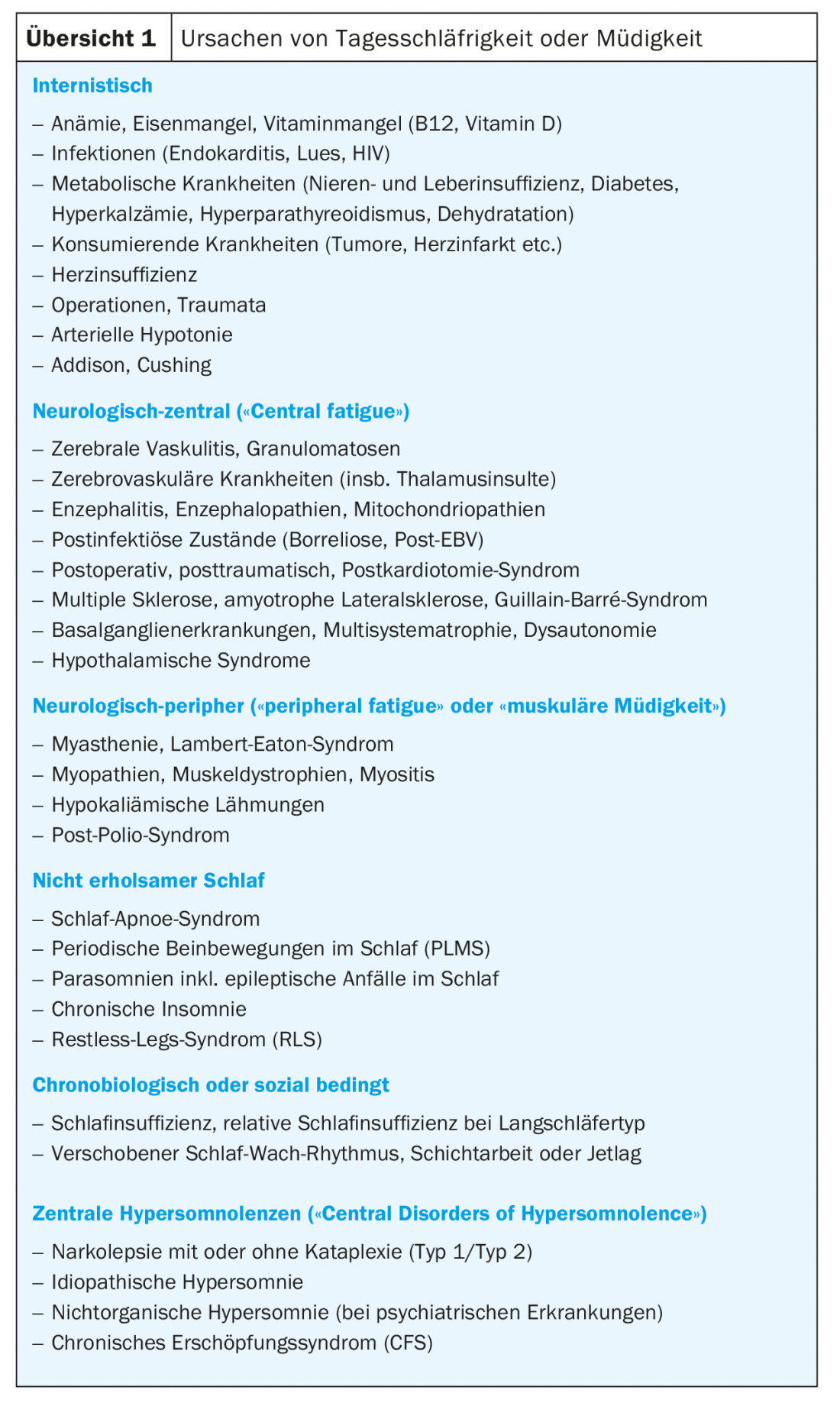

Daytime sleepiness, hypersomnia, fatigue or exhaustion (fatigue) are common symptoms in the practice of every physician, which require the most accurate diagnosis possible before targeted therapy can be given [5]. In addition to a detailed medical history including longitudinal course and any associations with somatic or psychiatric disorders and a clinical examination, the general practitioner will also take a broad laboratory to rule out internal causes (Overview 1).

Socially determined causes – such as an absolute or (in the case of long sleepers) also a relative sleep insufficiency, an unfavorable sleep hygiene with variable bedtime and rising times and a shifted sleep-wake rhythm – must be clarified in a test period over several weeks with regular and sufficient sleep. A socially or externally induced sleep deficit of one hour per night compared to the individual sleep requirement can already lead to daytime sleepiness. Surprisingly, however, chronic insomnia tends to result in fatigue but rarely in sleepiness and is more comparable to caffeine intoxication. In restless legs syndrome, both are possible. Delayed sleep phase syndrome (“DSPS”), which occurs especially during adolescence, is characterized by the simultaneous occurrence of insomnia of falling asleep and difficult awakening, which is absent during vacations when the rhythm is “free-running.”

In a next step, PSG is used to clarify the most common causes of non-restorative sleep such as sleep apnea, periodic leg movements during sleep (PLMS), and various parasomnias including epileptic seizures during sleep [1].

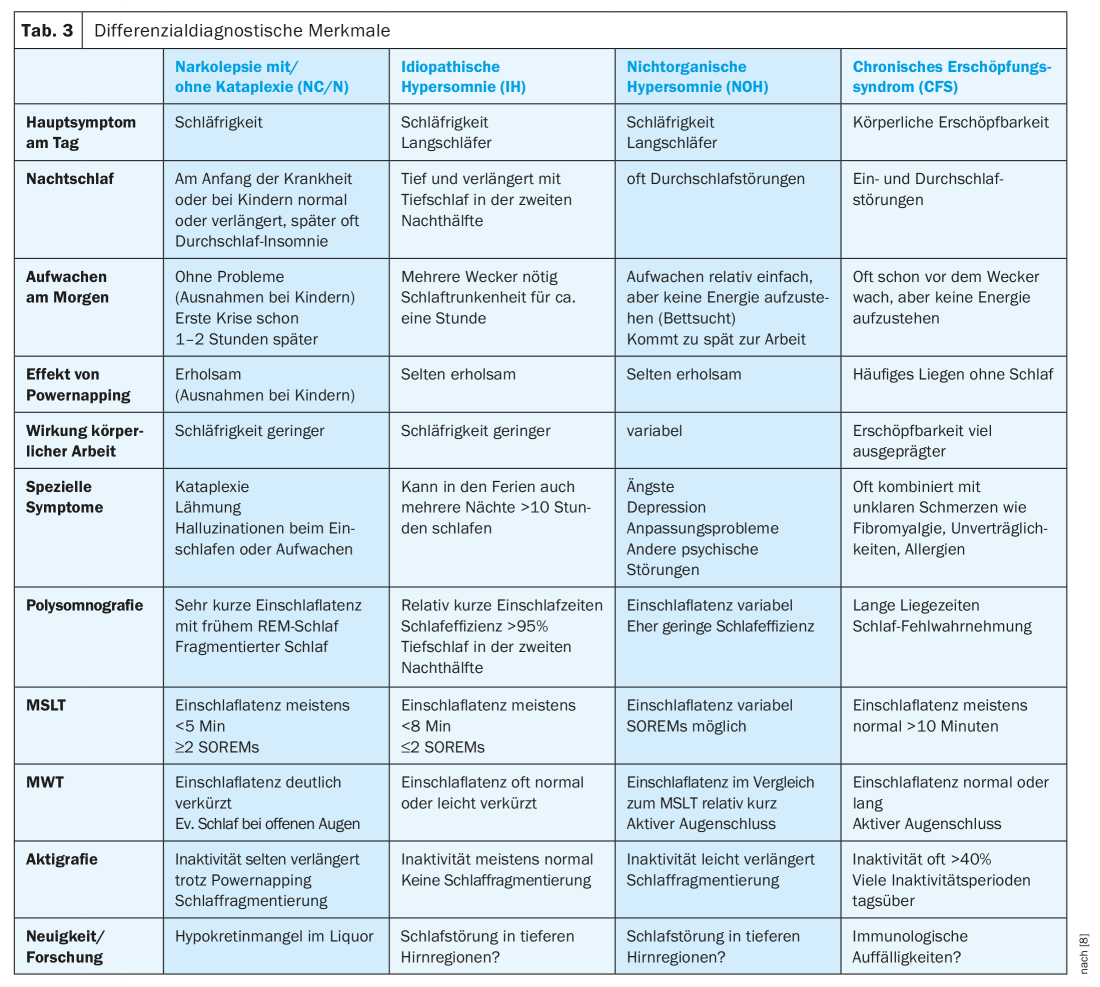

Once the secondary forms of daytime sleepiness have been excluded, a small group of primary hypersomnolence remains, which, in addition to narcolepsy with and without cataplexy, includes idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) and nonorganic hypersomnia (NOH). Because of the therapeutic consequences, these causes must be distinguished and differentiated from chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (Table 3).

Narcolepsy with or without cataplexy

Narcolepsy is not rare, with a prevalence of 1:3000 in the normal population. A distinction is made between narcolepsy with cataplexy (type 1) from narcolepsy without cataplexy (monosymptomatic narcolepsy, type 2) [1,2,6].

Narcolepsy is a potentially invalidating disorder of sleep and wakefulness structure, characterized by the pentad 1) Sleep attacks, 2) affective loss of tone (cataplexy, type 1 only), 3) hypnagogic hallucinations, 4) Sleep paralysis and 5) disturbed night sleep including distressing dreams. The disease often begins during an important period of life during apprenticeship or school between the ages of 15 and 25, and rarely much later. Usually daytime sleepiness occurs first and cataplexies often occur over the course of the following months, rarely years later, and never at all in type 2. Hypnagogic hallucinations and or sleep paralysis are described by only about 60% of patients.

Pronounced daytime sleepiness, often with an Epworth Score of >15 points and/or in the form of irresistible attacks of falling asleep, is virtually always the chief complaint. Adults not infrequently report trouble-free awakening in the morning or even sleep-through insomnia, whereas children and adolescents often report a deep, prolonged need for sleep per 24 hours with difficult awakening and sleep drunkenness. Daytime naps are usually short and restful in adults, but often long and not restful in children. REM sleep behavior disorder can occur very early in children, restless legs syndrome and PLMS, respectively, tend to be late symptoms. In many patients, significant weight gain is observed at the onset of the disease, which may also explain the higher incidence (approximately 10%) of sleep apnea and, in children, the premature onset of puberty.

Pathognomonic for type 1 are emotionally triggered attacks of weakness (cataplexy) of the head holding muscles, eyelids, mandible or dysarthria in the first seconds of emotion. In younger patients, cataplexies may also take the form of facial grimaces, such as repeated opening of the mouth, sticking out the tongue, or unusual twitching and cramping. Pseudocataplexy in healthy individuals is described as weakness in the knees after prolonged hearty laughter or in stressful situations.

The diagnosis is generally made on the basis of typical clinical symptoms and typical results from additional examinations such as PSG, MSLT, multiple wakefulness test ( MWT) and actigraphy (Tab. 3). A strongly reduced hypocretin level in the CSF is decisive for a definite diagnosis.

According to ICSD-3 classification, either the decreased hypocretin level or a latency to fall asleep <8 minutes and ≥2 Sleep Onset REM periods (SOREM) in the MSLT are required, with a SOREM in the preceding PSG also counting [2]. The positive HLA-DQB1*0602 allele can be detected in 98% of typical narcolepsy cataplexy and in approximately 40% of monosymptomatic narcolepsy (type 2) compared with a prevalence of approximately 24% in the normal population. This means that a negative HLA should cast some doubt on the diagnosis, but positive detection in no way proves the diagnosis.

The cause of narcolepsy is thought to be an autoimmune reaction with destruction of hypocretin-forming cells in the lateral hypothalamus, which occurs only in genetically predisposed individuals after certain exogenous influences such as streptococcal or viral infection [7].

Symptomatic treatment

Therapy aims to enable the completion of school or apprenticeship and the pursuit of a profession. This involves combining fixed scheduled daytime sleep breaks with stimulants such as modafinil, methylphenidate, or off-label pitolisant and other amphetamines to combat daytime sleepiness.

When cataplexies are disruptive in appearance or could be dangerous in occupational activities, gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB) is now considered a first-line agent. During the short pharmacological effect over 3-4 hours, there is also a positive effect on the often fragmented night sleep and unpleasant dreams. Sometimes there is a slight improvement in daytime sleepiness.

Antidepressants such as clomipramine may be used as an alternative to suppress cataplectic attacks when GHB is not tolerated or an antidepressant effect is desired.

Difficult differential diagnosis

In order to distinguish narcolepsy from the even rarer IH, NOH and CFS, in addition to a very precise anamnesis, comprehensive apparative diagnostics are usually necessary in the sleep-wake center. (Tab. 3). Because of the therapeutic consequences, the differentiation between organically caused narcolepsy and IH and the mainly psychiatrically caused NOH and CFS is essential [8].

A very rare passive form of hypersomnia, which presents with psychiatric abnormalities and sometimes hyperphagia and hypersexuality at intervals of weeks to months, is known as Kleine-Levin syndrome [1].

Assessment of fitness to drive

In patients with daytime sleepiness, assessment of fitness to drive is part of every physician’s duty of care and should be discussed at the initial consultation and noted in the patient’s records [9]. In the case of private vehicle drivers who have never caused a microsleep accident, it is sufficient to instruct the patient that he or she must refrain from driving a motor vehicle if drowsy. The only effective countermeasures (stopping for a coffee and subsequent power napping) and the consequences of a microsleep accident (revocation of identity card, fine up to imprisonment and insurance recourse) should also be pointed out. In the case of professional drivers, periodic driving fitness tests ordered by the authorities or car drivers who have already caused a microsleep accident, referral to a sleep-wake center for clarification of the cause and quantification of daytime sleepiness in the MWT with optimal therapy is recommended [10], in particular also before a report to the authorities is made.

Take-Home Messages

- Daytime sleepiness is not synonymous with narcolepsy. However, because of the colorful clinical picture, any daytime sleepiness or daytime drowsiness is worth thinking about early as well – not just a sleep deficit, internal or psychiatric causes, and common sleep apnea.

- To exclude various sleep-disrupting factors (sleep apnea, parasomnias, sleep-related epileptic seizures), video-polysomnography is essential.

- Typical emotionally triggered facial muscle weaknesses allow the diagnosis of narcolepsy with cataplexy (type 1).

- An important diagnostic test, esp. for monosymptomatic narcolepsy (type 2), is the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT). Narcolepsy is present with a mean sleep onset latency of <8 minutes and at least two early REM periods.

- Detection of severely reduced or absent hypocretin in CSF is conclusive for the diagnosis of narcolepsy-cataplexy (type 1), but a normal value does not exclude narcolepsy type 2.

- A positive HLA-DQB1*0602 is not evidence of narcolepsy.

Literature:

- Mathis J, Hatzinger M: Practical diagnostics in fatigue/sleepiness. Swiss Arch Neurol Psychiatr 2011; 162: 300-309.

- AASM: International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Third Edition (ICSD-3). 2014.

- Bloch KE, et al: German Version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Respiration 1999; 66(5): 440-447.

- Krupp LB, et al: The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989; 46(10): 1121-1123.

- Stadje R, et al: The differential diagnosis of tiredness: a systematic review. BMC Family Practice 2016; 17: 147.

- www.narcolepsy.ch

- Mathis J, Strozzi S: Narcolepsy, a consequence of H1N1 influenza vaccination? Switzerland Med Forum 2012; 12: 8-10.

- Mathis J: Narcolepsy and other “central hypersomnolence”. Practice 2018; 107: 1161-1167.

- Mathis J, Seeger R, Ewert U: Excessive daytime sleepiness, crashes and driving capability. Swiss Arch Neurol Psychiatr 2003; 154: 329-338.

- Mathis J, et al: Fitness to drive in daytime sleepiness. Recommendations for physicians and accredited sleep medicine centers. Swiss Med Forum 2017; 17(20): 442-447.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(3): 12-16

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(4): 10-13.