The nonspecific symptoms in the early stages lead to a significant diagnostic latency of these primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Extracorporeal photopheresis and new targeted therapies are increasingly improving therapeutic success in Sézary syndrome.

Sézary syndrome is a rare, often difficult to diagnose, aggressive disease belonging to the group of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) [1,2]. The disease belongs to the extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas and is characterized by the triad of pruritic erythroderma, generalized lymphadenopathy, and neoplastic T cells with cerebriform nuclei (Sézary cells) in blood, skin, and lymph nodes [3,25]. Sézary syndrome occurs mainly between the ages of 40 and 60, with an incidence of 0.1/100,000 . Men and African Americans are more likely to be affected than women and Caucasians [4,5].

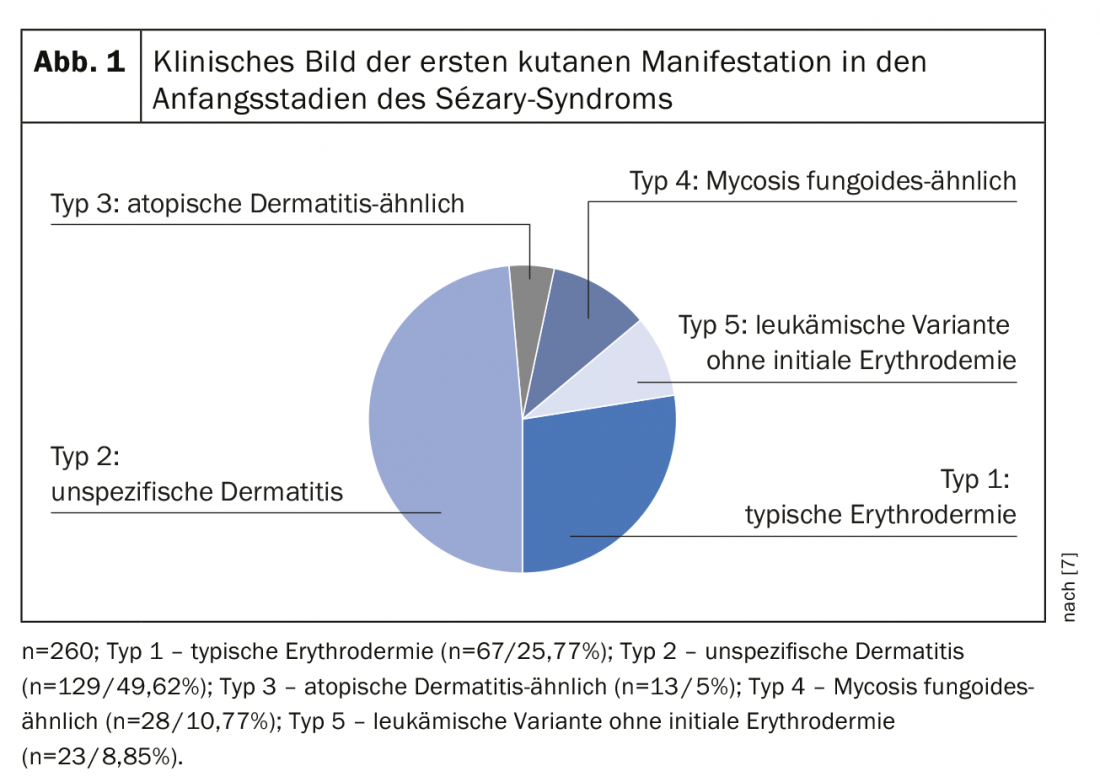

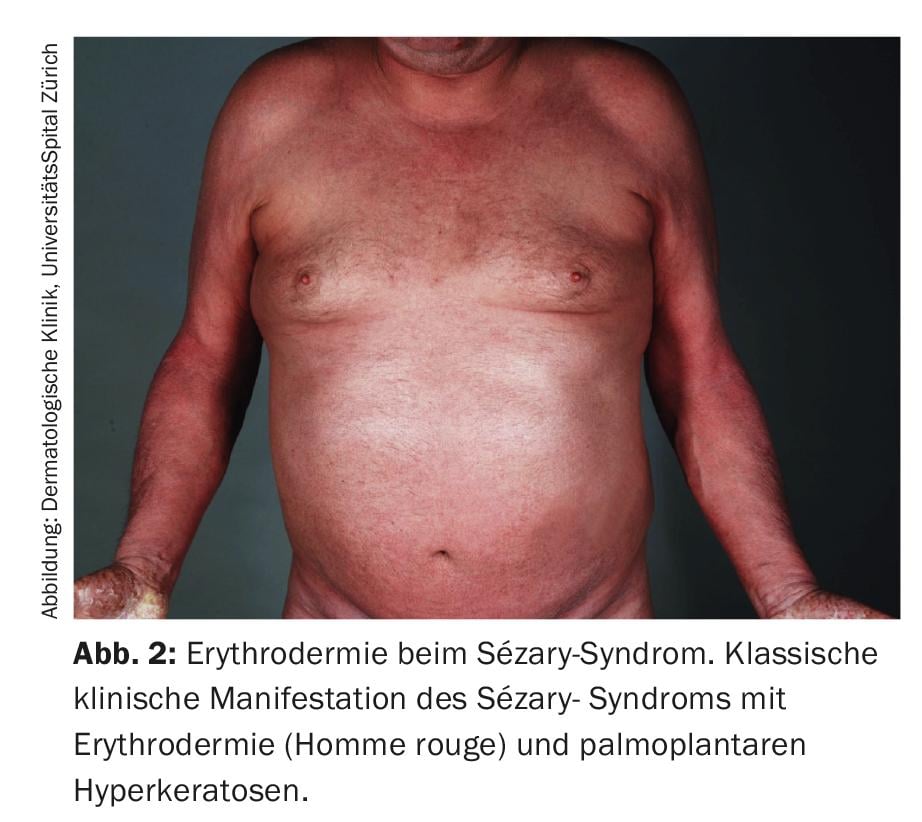

The definition of Sézary syndrome by the International Cutaneous Lymphoma Society together with the World Health Organization includes erythroderma as a compelling symptom accompanied by at least two of the following manifestations: >1000 Sézary cells/µL in peripheral blood, immunophenotypic T-cell abnormalities CD4/CD8 ratio ≥10, CD4+/CD7- cells ≥30%, or CD4+/CD26- cells ≥ 40%. [25], presence of a monoclonal T-cell receptor (TZR) population in the blood or chromosomally altered T-cell clones [6]. A published retrospective cohort study by Mangold et al. however, showed that only 25.5% of patients present with the typical erythroderma, which affects >80% of the body surface, as the initial manifestation. However, in 86.3% of patients, erythroderma develops over time and is present no later than the time of diagnosis. The initial often nonspecific clinical presentation is therefore responsible for diagnostic delays ranging from one month to 32 years (mean 4.2 years) (Fig. 1) [7]. Other symptoms of Sézary syndrome include alopecia, onychodystrophy, palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, and massive pruritus, which exerts a great deal of suffering on affected patients (Fig. 2). With the loss of cutaneous integrity comes an increased risk of infection by resident skin flora such as Staphylococcus aureus. Tumorous skin infiltrates associated with edema as well as hypalbuminemia may result in fluid loss.

Diagnosis

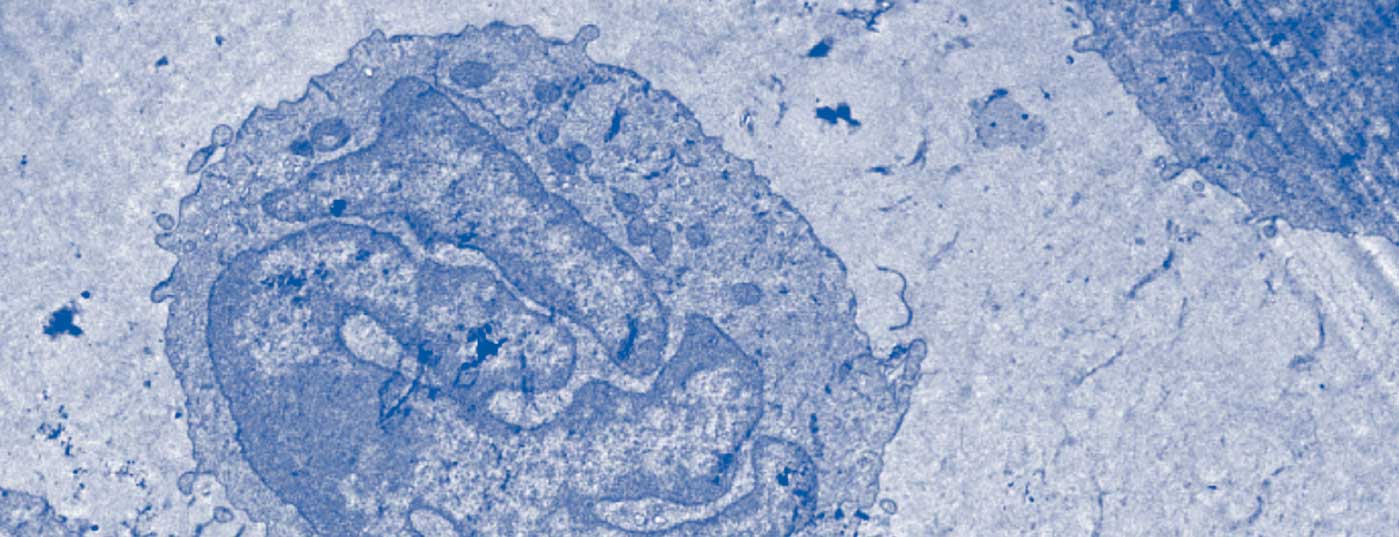

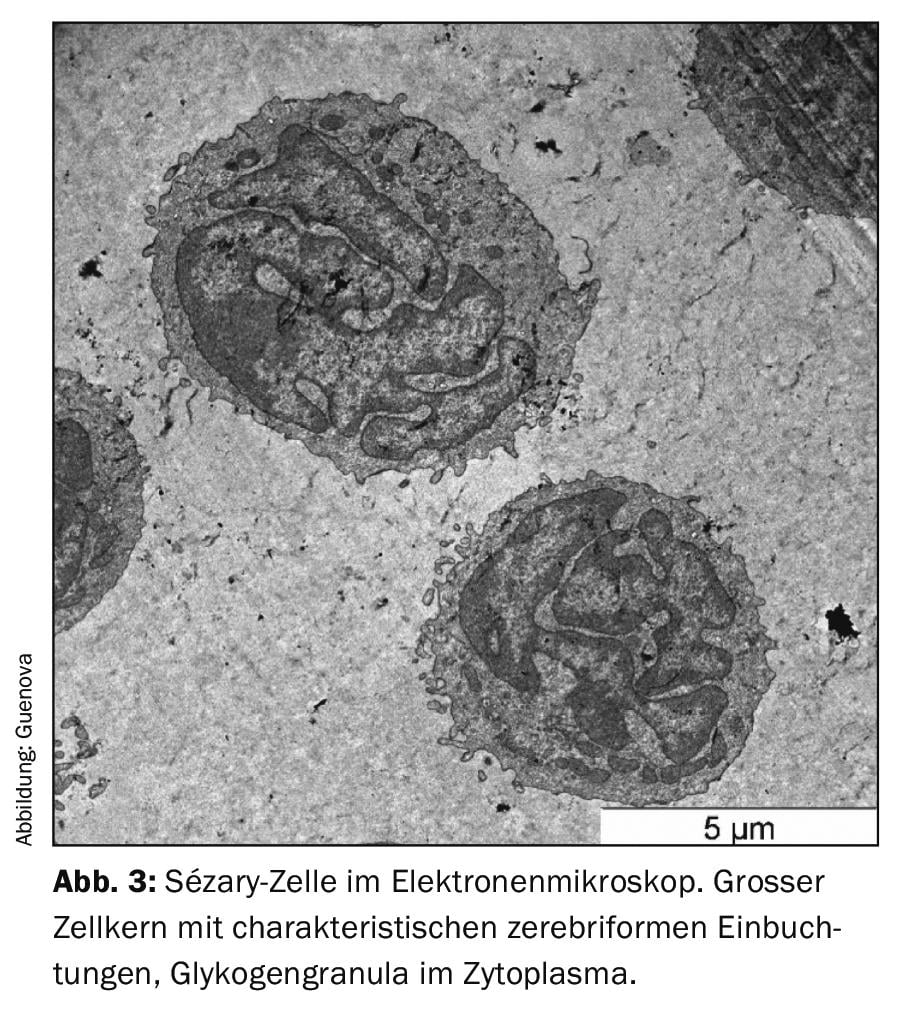

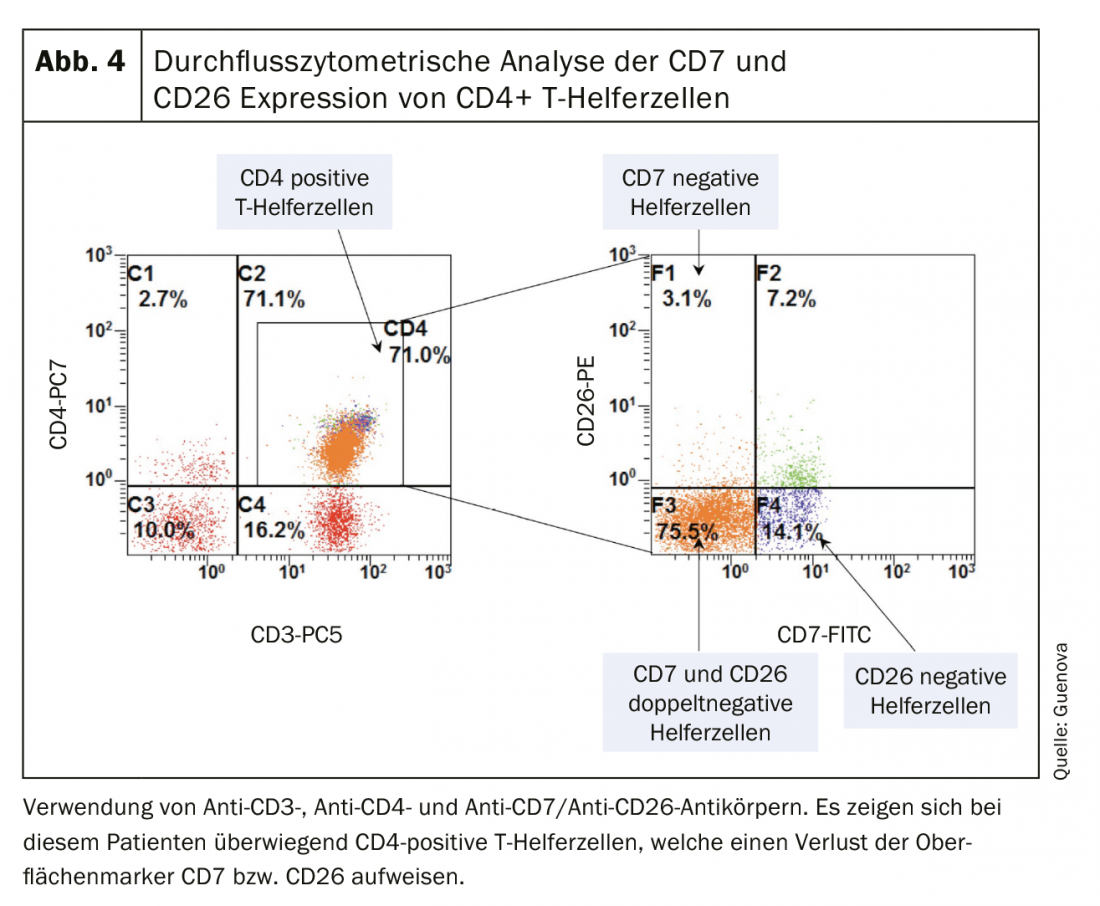

As with many erythrodermic skin diseases, the lack of clear diagnostic markers in Sézary syndrome, among others, makes differential diagnosis a challenge [3,8]. The essential clinical examination includes palpation of all lymph node regions in addition to a most accurate survey of the skin status. The so-called “Modified Skin Weighted Assessment Tool” (mSWAT) [8,9] is particularly suitable for measuring and evaluating skin involvement. Multiple biopsies of representative skin lesions are examined by histopathological as well as immunohistochemical methods [3]. Histologically, monomorphic infiltrates of atypical T cells, characteristic epidermotropy, and Pautrier’s microabscesses – intraepidermal accumulations of malignant cells – can be seen [8]. However, in about 40% of cases, histologic findings are inconclusive for the diagnosis [10]. Peripheral blood is examined by flow cytometry and molecular or cytogenetic methods for the presence of an abnormal CD4+ T cell population as well as morphologically conspicuous, neoplastic T cells (blood smear). These typical Sézary (or also known as Lutzner) cells are characterized by an ultrastructural morphology with their cerebriform indented nucleus (Fig.3). They not only express the chemokine receptors CCR7 and CCR4, but also exhibit increased expression of L-selectin and a characteristic deficiency of the surface antigens CD7 and CD26 (Fig.4) [3,11]. The detection of T-cell receptor clonality has a high diagnostic value [12]. Its molecular biological detection by polymerase chain reaction has been established as the standard [13]. Flow cytometric analysis of T-cell receptor Vβ antigen is routinely used in specialized university centers [12].

Recent analyses demonstrated increased expression of the surface antigen CD164 in total CD4+ T-cell counts in patients with Sézary syndrome. This marker may therefore act as a promising diagnostic parameter and potential therapeutic target in the future [14,15]. Additional novel blood and skin biomarkers, including PD-1 (CD279) and KIR3DL2 (CD158k), may help distinguish Sézary syndrome from erythrodermic inflammatory dermatoses [25].

Staging and prognosis

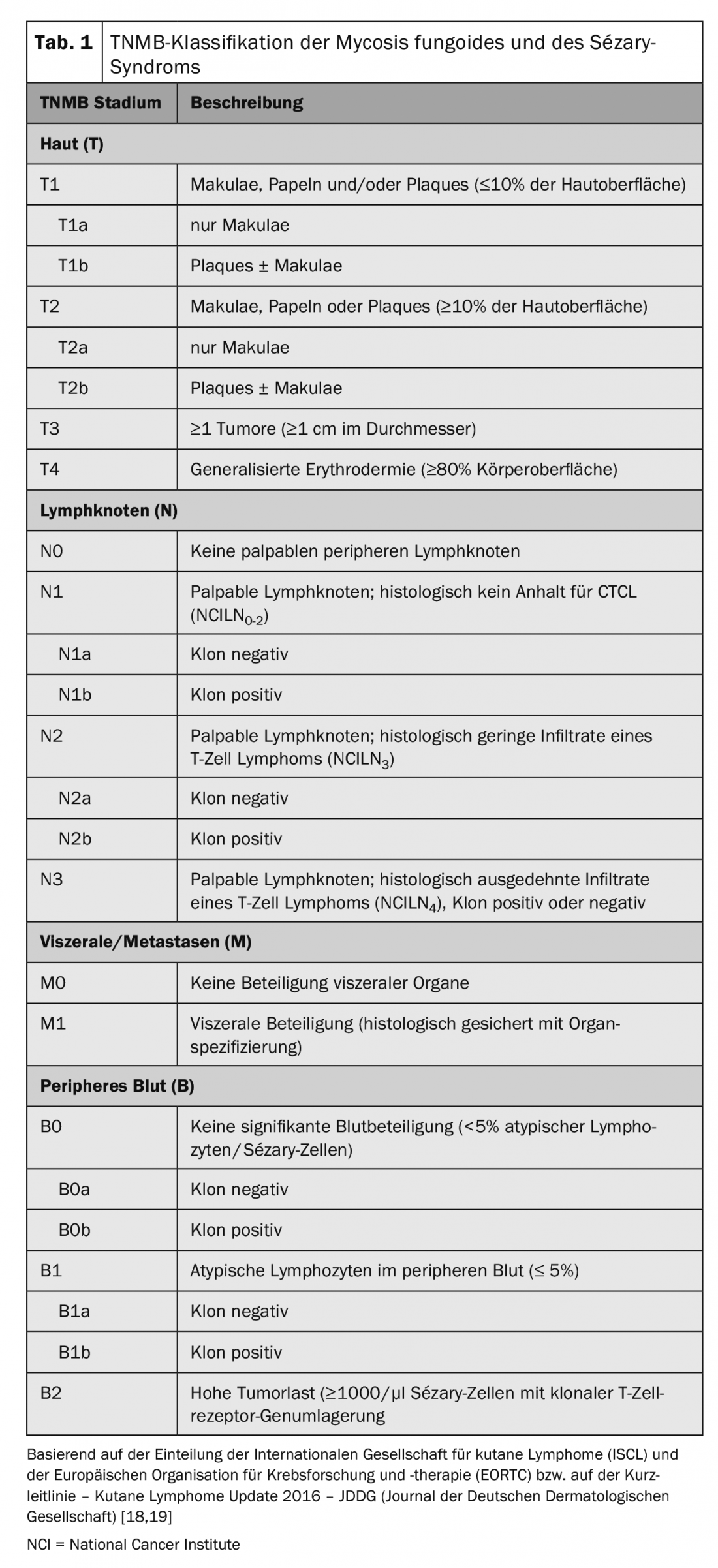

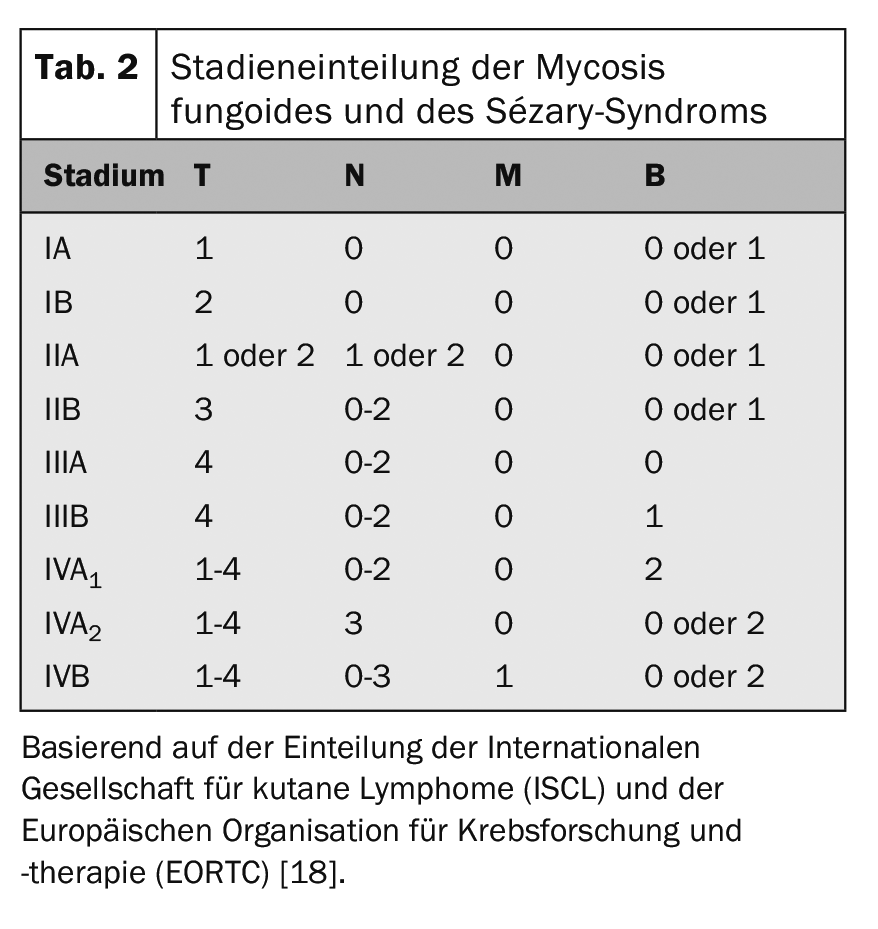

The internationally recognized TNM classification is used for tumor staging of CTCL (Table 1). In addition to skin involvement – primary tumor (T), lymph node involvement (N) and distant metastases – this includes (M) – also the detection of Sézary cells in the peripheral blood (B) and is thus referred to as TNMB classification (Tab. 1). This classification is used to classify the stages (Tab. 2). Sézary syndrome with its compelling blood involvement therefore always corresponds to stage IV [16]. Accordingly, the disease has a poor prognosis with a median survival rate of <3 years. In addition to peripheral blood involvement, other negative prognostic factors have been identified: atypical phenotypes and characteristic loss of surface CD7 and CD26 features [17].

Imaging studies such as whole-body CT and lymph node ultrasonography as part of initial tumor staging are recommended for all patients at stage T2 and above [8,20]. PET-CT and lymph node biopsy should be performed in patients with suspected lymphadenopathy and/or systemic spread [8,16]. Bone marrow biopsy should be performed in patients with hematologic abnormalities. Advanced diagnostics and biopsies of visceral organs may be considered if extracutaneous involvement is suspected [8]. Sézary syndrome patients should optimally be managed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of dermatologists, oncologists, dermatopathologists as well as radiologists both diagnostically and therapeutically [16].

Etiology

Although the cause of this complex disease is still not fully understood, it can be assumed that the pathophysiology of Sézary syndrome can be explained on the one hand by immune dysfunction and on the other hand by epigenetic alterations [21]. Until recently, the Sézary syndrome karyotype was thought to be characterized by deletions affecting chromosomes 10q and 17p and insertions affecting chromosomes 8q, 10p, and 17q [8]. A study by Izykowska et al. shows that the malignant changes, however, occur at a wide variety of genetic levels [21,22]. As with most leukemic CTCLs, there is a predominantly Th2-heavy immune response in Sézary syndrome [23]. The Th2-type cytokines interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-13, IL-21, and IL-31, which are released in high amounts, suppress the Th1-mediated immune response and also serve as pharmacological targets [3,21].

Differential diagnosis

Differentially, Sézary syndrome is particularly difficult to distinguish from mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common of all CTCL. Clinically and diagnostically, both diseases have many similarities. Campbell et al. However, were able to show that Sézary syndrome and MF arise from distinct functional T cell subsets and thus they should be considered separate lymphomas [3,24]. While blood involvement is absent or minimal in MF, it is an essential component in Sézary syndrome [7]. Other non-neoplastic differential diagnoses of Sézary syndrome include erythrodermia psoriatica, atopic dermatitis or other forms of dermatitis, pytiriasis rubra pilaris, drug reactions, and idiopathic erythroderma. Differentiating early-stage Sézary syndrome from erythrodermic inflammatory dermatoses can be challenging.

Therapy

The treatment of Sézary syndrome, which in most cases still cannot achieve a complete cure, is primarily based on the extent of the disease, the impact on quality of life, prognostic factors, and patient age or comorbidities [16]. According to the JDDG’s latest Sézary syndrome therapy update, extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), which has few side effects, is among the first-line treatment modalities. ECP can be used as monotherapy or in combination with topical corticosteroids, phototherapy using psoralenes with UV-A (PUVA), or systemically with interferon alpha (INF-α) or bexarotene [19,26].

Low doses of the folic acid antagonist methotrexate, systemically administered retinoids (bexarotene; both also combined with PUVA and ECP), the cytostatic chlorambucil in combination with a low-dose glucocorticoid, and whole-skin electron irradiation are recommended as “second-line” therapy [19,20,26]. In advanced stages of Sézary syndrome, monochemotherapy using gemcitabine or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are among the second-line therapies.

In recent years, therapeutic success has increasingly improved thanks to targeted cancer therapy. Alemtuzumab, a humanized anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody, was studied in a phase II trial in 22 patients with advanced MF/SS, with response rates at 55% [27].

Because of the significantly increased risk for infectious complications, subcutaneous administration of the drug at a low dose was studied in a cohort of 14 patients with refractory SS , with response rates of more than 80% [28]. The antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin is not yet approved for Sézary syndrome, but may be used as an off-label preparation for CD30+ variants of Sézary syndrome, if appropriate. The folic acid antagonist pralatrexate is approved for peripheral T-cell lymphoma. A randomized phase III clinical trial comparing the CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab versus vorinostat (MAVORIC) demonstrated a significant improvement in progression-free survival in MF/SS patients randomized to mogamulizumab. Patients with Sézary syndrome had the highest overall response (37%) [29].

Several histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACs) that interfere with epigenetic regulation of transcription have already been approved outside Europe for the treatment of Sézary syndrome [20]. In Europe, the HDAC inhibitor resminostat is currently being tested in clinical trials as maintenance therapy for patients with advanced SS and MF against placebo. The immune checkpoint inhibitors anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4 are now approved for the treatment of multiple solid tumors, including melanoma. Preliminary data from a phase II trial of pembrolizumab (anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody) in relapsed/refractory MF and SS appear promising with response rate of 33%, even in patients with advanced disease [30].

Currently, the only treatment option with curative potential is allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Although long-term remissions can be observed with this therapy, the increased transplant-associated mortality and morbidity should not be underestimated [16,20]. Despite all scientific progress, the therapy of Sézary syndrome, apart from stem cell transplantation, remains palliative to this day.

Despite the currently poor prognosis of this disease, there is hope that recent findings regarding Sézary syndrome as an independent clinical picture and the associated diagnostic and therapeutic advances will improve the chances of recovery and the quality of life of those affected.

Take-Home Messages

- Only 25.5% of Sézary syndrome patients present with classic erythroderma as the initial manifestation.

- Blood involvement is an essential component of Sézary syndrome and differentiates it from other primary cutaneous lymphomas.

- The nonspecific symptoms of the disease in the early stages result in significant diagnostic latency.

- Extracorporeal photopheresis and new targeted therapies (e.g., using humanized monoclonal antibodies) are increasingly improving therapeutic success in Sézary syndrome.

- Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is currently the only treatment option with curative potential.

Literature:

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, et al: The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016; 127(20): 2375-2390.

- Scarisbrick JJ, Prince HM, et al: Cutaneous Lymphoma International Consortium Study of Outcome in Advanced Stages of Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: Effect of Specific Prognostic Markers on Survival and Development of a Prognostic Model. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(32): 3766-3773.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, et al: Sézary Syndrome and Atopic Dermatitis: Comparison of Immunological Aspects and Targets. Biomed Res Int 2016; article id: 9717530.

- Bradford PT, SS D, et al: Cutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: a population-based study of 3884 cases. Blood 2009; 113(21): 5064-5073.

- Wilson LD, Hinds G, Yu JB: Age, race, sex, stage, and incidence of cutaneous lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2012; 12(5): 291-296.

- Vonderheid EC, Bernengo MG, et al: Update on erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46(1): 95-106.

- Mangold AR, Thompson AK et al: Early clinical manifestations of Sézary syndrome: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; pii: S0190-9622(17): 31784-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.036. [Epub ahead of print].

- Foss FM, Girardi M: Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2017; 31(2): 297-315.

- Stevens SR, Ke MS, et al: Quantifying skin disease burden in mycosis fungoides-type cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: the severity-weighted assessment tool (SWAT). Arch Dermatol 2002; 138(1): 42-48.

- Trotter MJ, Whittaker SJ, Orchard GE, Smith NP: Cutaneous histopathology of Sézary syndrome: a study of 41 cases with a proven circulating T-cell clone. J Cutan Pathol 1997; 24(5): 286-291.

- Boonk SE, Zoutman WH, et al: Evaluation of Immunophenotypic and Molecular Biomarkers for Sézary Syndrome Using Standard Operating Procedures: A Multicenter Study of 59 Patients. J Invest Dermatol 2016; 136(7): 1364-1372.

- Gibson JF, Huang J et al: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL): current practices in blood assessment and the utility of T-cell receptor (TCR)-Vbeta chain restriction. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74(5): 870-877.

- Lukowsky A, Muche JM et al: Evaluation of T-cell clonality in archival skin biopsy samples of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas using the biomed-2 PCR protocol. Diagn Mol Pathol 2010; 19(2): 70-77.

- Guenova E, Ignatova D et al: Expression of CD164 on Malignant T cells in Sézary Syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol 2016; 96(4): 464-467.

- Benoit BM, Jariwala N, et al: CD164 identifies CD4+ T cells highly expressing genes associated with malignancy in Sézary syndrome: the Sézary signature genes, FCRL3, Tox, and miR-214. Arch Dermatol Res 2017; 309(1): 11-19.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, et al: Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70(2): 223.e1-17.

- Scarisbrick JJ, Kim YH, et al: Prognostic factors, prognostic indices and staging in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: where are we now? Br J Dermatol 2014; 170(6): 1226-1236.

- Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, et al: Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood 2007; 110(6): 1713-1722.

- Dippel E, Assaf C, Becker J, Bergwelt M, Beyer M: S2k – Brief Guideline – Cutaneous Lymphomas (ICD10 C82 – C86) Update 2016. JDDG 2017; [in Vorbereitung].

- Trautinger F, Eder J, et al: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome – Update 2017. Eur J Cancer 2017; 77: 57-74.

- DeSimone JA, Sodha P, Ignatova D, et al: Recent advances in primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol 2015; 27(2): 128-133.

- Izykowska K, Przybylski GK, et al: Genetic rearrangements result in altered gene expression and novel fusion transcripts in Sézary syndrome. Oncotarget 2017; 8(24): 39627-39639.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R et al: TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19(14): 3755-3763.

- Campbell JJ, Clark RA, et al: Sézary syndrome and mycosis fungoides arise from distinct T-cell subsets: a biologic rationale for their distinct clinical behaviors. Blood 2010; 116(5): 767-771.

- Willemze et al: The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas, Blood (2019) 133 (16): 1703-1714.

- Dippel E, et al: S2k guideline – Cutaneous lymphomas update 2016 – part 2: therapy and follow-up (ICD10 C82 – C86), J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018 Jan;16(1): 112-123.

- Lundin J, Hagberg H, Repp R, et al. Phase 2 study of alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) in patients with advanced mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome. Blood. 2003;101: 4267-4272.

- Bernengo MG, Quaglino P, Comessatti A, et al: Low-dose intermittent alemtuzumab in the treatment of Sezary syndrome: clinical and immunologic findings in 14 patients. Haematologica 2007; 92: 784-794.

- Kim YH, et al: Mogamulizumab vs vorinostat in previously treated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (MAVORIC): an international, open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19: 1192-1204).

- Phillips T, Devata S, Wilcox RA: Challenges and opportunities for checkpoint blockade in T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. J Immunother Cancer 2016; 4: 95.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(6): 14-18