Type 2 diabetes often develops insidiously and over a long period of time. In those under 50, metabolic syndrome is often associated. Special attention should be paid to cardiovascular risk reduction in this age group. What this means in concrete terms and what other current findings there are in this regard were reported by Prof. Jochen Seufert, MD, at DGIM 2019.

The age criterion for “young” type 2 diabetics is arbitrary, according to Prof. Dr. med. Jochen Seufert, Head of the Department of Endocrinology and Diabetology at the University Hospital Freiburg im Breisgau (D) [1]. The prevalence in under 50-year-olds is approximately 5-10%, depending on the database, and he decided to use this as a cut-off in his presentation [1].

The age group of affected children and adolescents (11-18 years) in Germany accounted for only a small proportion (approximately 12 to 18 per 100,000 persons according to 2014-2016 data) [2]. The speaker pointed out that age-related prevalence and incidence rates of type 2 diabetes vary regionally worldwide [1]. A guideline for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in childhood and adolescence does not exist. Apart from insulin, there are no approved antidiabetic drugs for this age group, which is why a focus on individually tailored non-drug lifestyle interventions (diet, exercise, weight reduction, etc.) is important. In type 2 diabetics over 18 years of age, the entire spectrum of antidiabetic drugs is available, although some special features should be taken into account compared with older patients.

Often a gradual development

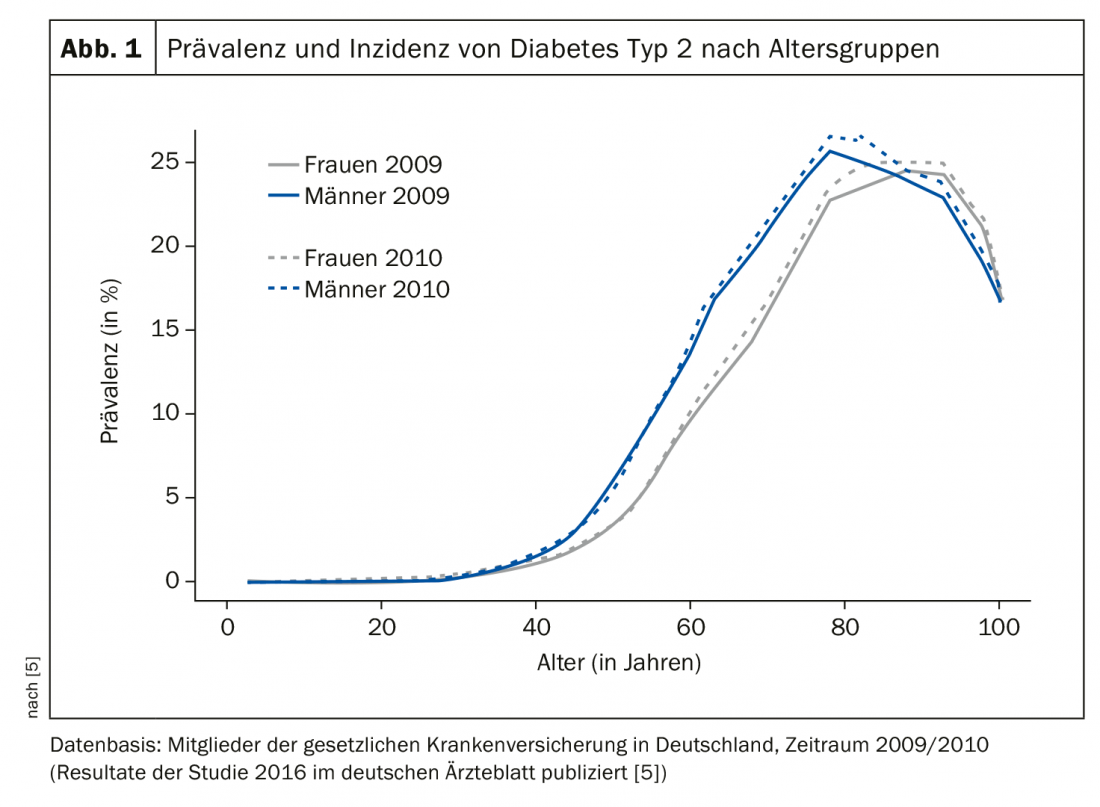

It is common for glucose levels to be elevated for a period of time but not diagnosed clinically, he said. This phase can extend over a period of about 3-7 years [3]. Globally, on average, approximately 50% of type 2 diabetes cases in the 20-79 age group are undiagnosed, with this proportion being approximately one-third in highly industrialized countries [3,4]. The bulk of type 2 diabetes sufferers are in the 70-90 age group, the speaker said. An analysis of a dataset published in 2016 on the prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Germany, with information from 65 million people insured by the statutory health insurance funds in 2009 and 2010, shows the following (Fig. 1) [5]: a jump in prevalence starting at age 50, with a peak at about age 80 (around 25%). After the age of 80 years, the prevalence was approximately 20-25% and decreased to 16.5% and 17.7%, respectively, in the age group of 100 years and older.

According to the IDF and WHO, diagnostic criteria for type 2 diabetes include symptoms such as fatigue, a strong feeling of thirst, frequent urination plus a value of ≥11.1 mmol/l (≥200 mg/dl) two hours after taking 75 g glucose in an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or a fasting glucose value ≥126 mg/dl (≥7.0 mmol/l) or a postprandial blood glucose level of 11.1 mmol/l (≥200 mg/dl) or an HbA1c level ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol) [7]. An advantage of HbA1c measurement is the high degree of standardization, it is a time-of-day independent test, and the cost is relatively low. When interpreting the HbA1c value, pre-existing conditions such as anemia, renal insufficiency, and hemoglobinopathies should also be taken into account [3].

According to the IDF and ADA, impaired glucose tolerance is defined as fasting blood glucose levels between 100 mg/dl-125 mg/dl (5.6 mmol/l-6.9 mmol/l) and/or HbA1c 5.7-6.4% (39-47 mmol/mol) [7,8]. This condition is also referred to as prediabetes and it is assumed that the number of undiagnosed cases is even higher than in type 2 diabetes [9]. Prediabetes is a condition that is considered a risk factor for the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease and is often associated with obesity, dislipidemia, and elevated triglyceride levels and/or low HDL cholesterol and hypertension [8]. The risk of cardiovascular events events (myocardial infarction, apoplexy, PAVK, heart failure) is lower the lower the HbA1c level is [10].

Cardiovascular risk reduction in focus

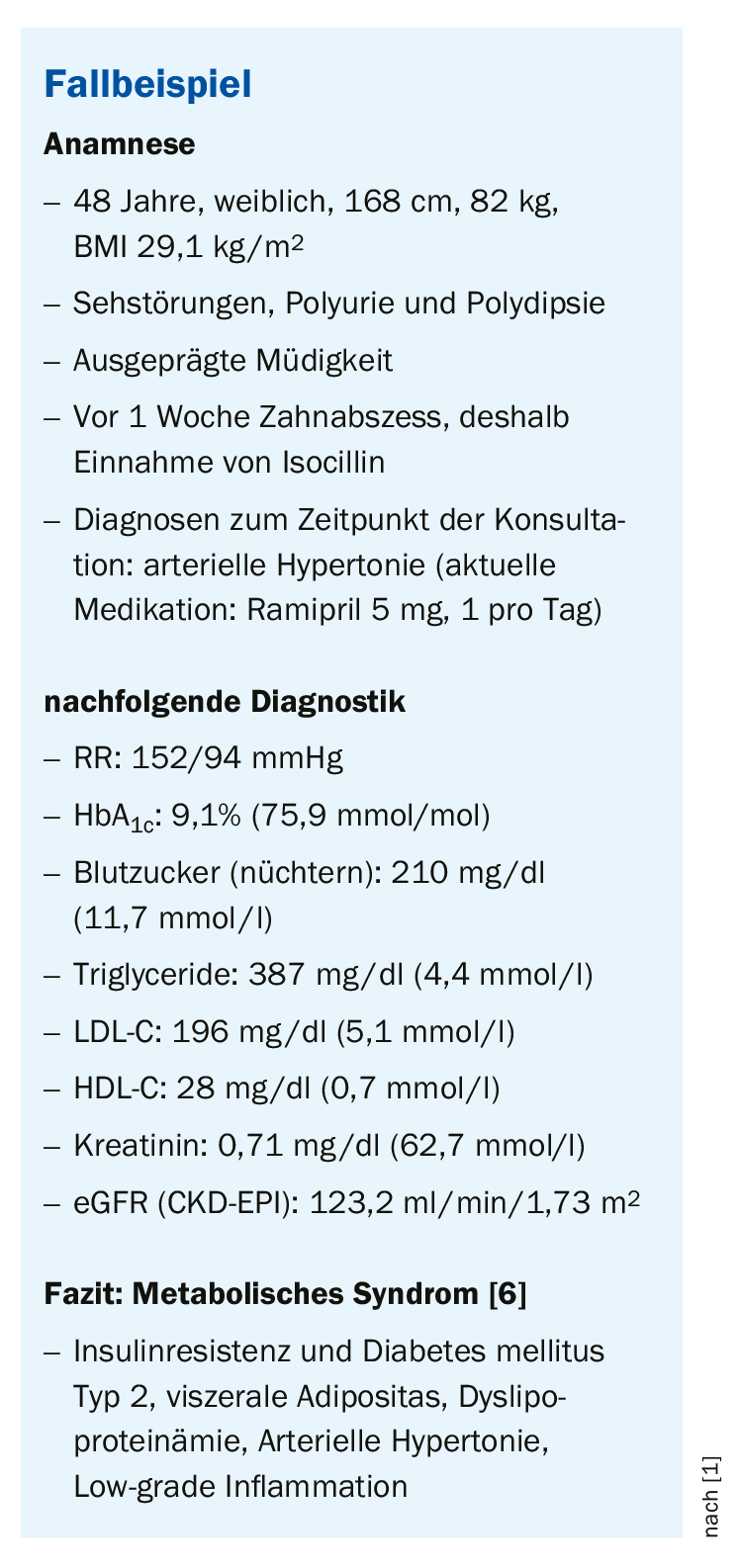

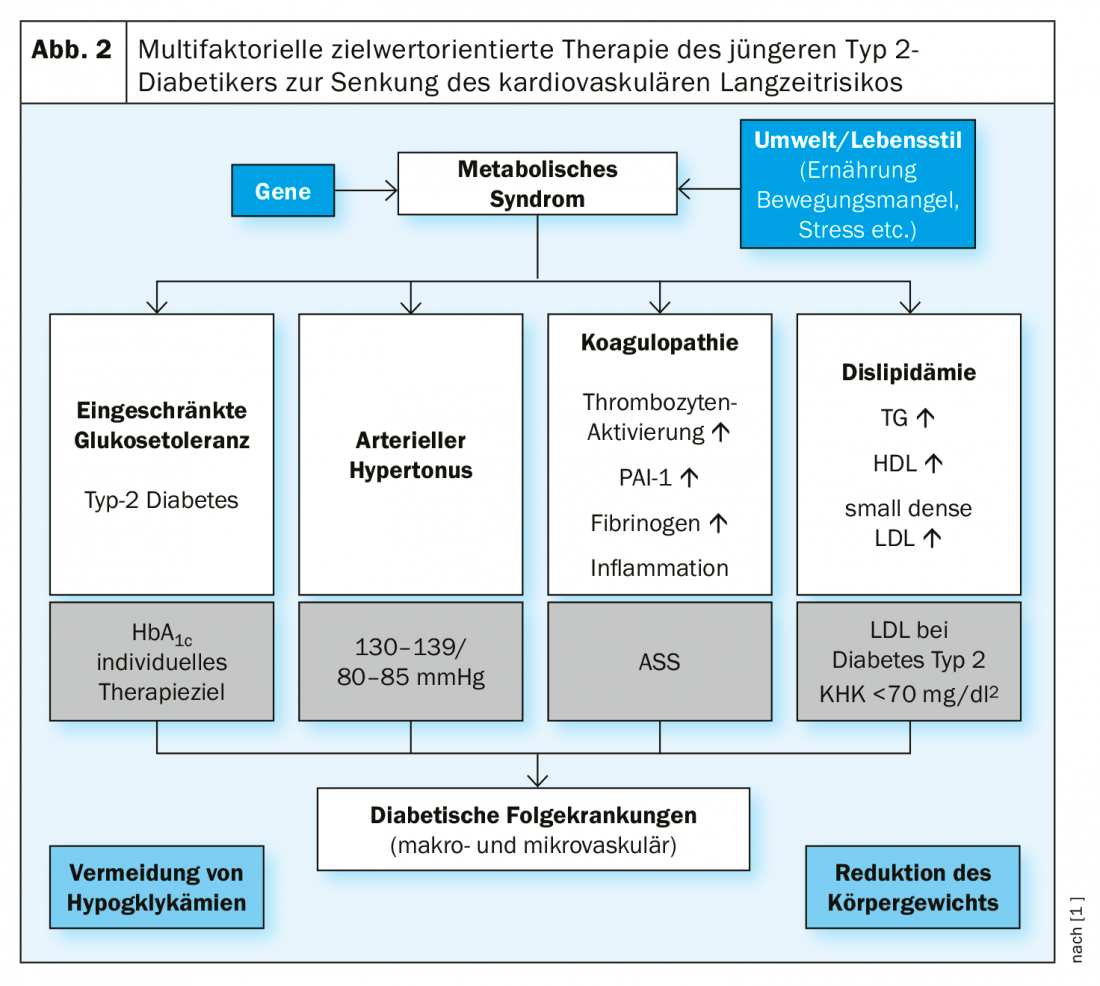

According to ADA 2019, criteria for metabolic (cardiovascular) syndrome are: Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, visceral obesity, dyslipoproteinemia, arterial hypertension, low-grade inflammation. This risk constellation must be recognized, especially in younger type 2 diabetics, because this is the main cause of cardiovascular disease and mortality in our latitudes. Younger diabetics (cut-off 50 years) also have a limited life expectancy due to diabetes and the main cause is cardiovascular deaths, as shown by relevant studies [11]. Efforts to reduce cardiovascular risk are important in this high-risk group, he said. A long-term therapy with a focus on the prevention of long-term complications should be aimed for, which also goes hand in hand with an increase in life expectancy, explains the speaker [6].

Compared to older patients, younger patients often have fewer comorbidities, which may have a positive impact on drug treatment options. For example, in the patient in the case study (box), renal function values were within the normal range, so contraindications to certain antidiabetic drugs associated with renal dysfunction need not be considered. Criteria for the selection of treatment options in younger type 2 diabetics are primarily proven reduction of clinically relevant endpoints and reduction of mortality. This can be achieved by multifactorial, goal-oriented therapy (Fig. 2).

The focus of treatment is on achieving target values regarding all symptoms of metabolic syndrome, as well as reduction of body weight and smoking cessation. As shown by data from the Danish longitudinal study Steno-2, this treatment strategy achieved a reduction in mortality and a reduction in microvascular and macrovascular complications [12–14].

Take-Home Messages

- Type 2 diabetes often develops insidiously over a long period of time.

- Many affected individuals under the age of 50 have a metabolic syndrome with associated cardiovascular risks.

- Multifactorial goal-directed therapy may help reduce long-term cardiovascular risk and mortality in type 2 diabetics younger than 50 [1,12–14].

- The focus of an appropriate intensive therapy regimen should be on treating the symptoms of metabolic syndrome: Glycemic control, dyslipidemia therapy, blood pressure lowering, platelet aggregation inhibition.

Source: DGIM 2019, Wiesbaden (D)

Literature:

- DGIM: Prof. Dr. med. Jochen Seufert, Head of the Department of Endocrinology and Diabetology, Clinic for Internal Medicine II, University Hospital Freiburg im Breisgau (D), Slide presentation: Therapy of the Younger Type 2 Diabetic, Clinical Symposium. 125. Congress of the German Society of Internal Medicine, Wiesbaden, May 5, 2019.

- Rosenbauer J: Journal of Health Monitoring 2019; 4(2) DOI 10.25646/5981.

- Forouhi NG, et al: Medicine 2019; 47(1): 22-27.

- International Diabetes Federation: IDF Diabetes Atlas 2017, www.idf.org/diabetesatlas

- Tamayo T, et al: Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113(11): 177-182; DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0177.

- American Diabetes Association: Diabetes Care 2019; 42(Suppl. 1): S13-S28. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S002

- IDF: Clinical Practice Recommendarions for managing Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care 2017, www.idf.org

- American Diabetes Association (ADA): Diabetes Care 42(Suppl. 1): S13-S28. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S002

- Greenberg R, Brookshier T: https://diabetesvoice.org

- Stratton IM, et al: BMJ 2000; 321(7258): 405-412.

- The emerging risk factors collaboration: N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 829-841. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862

- Gaede P, et al: N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 383-393.

- Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O: N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 580-591.

- Gaede P, et al: Diabetologia 2016; 59: 2298-2307.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(10): 25-26 (published 10/24/19, ahead of print).