Unnoticed over a long period of time, peripheral arterial disease entails serious consequences. The narrowed vessels increase the risk of cardiovascular events – and life expectancy is also significantly reduced.

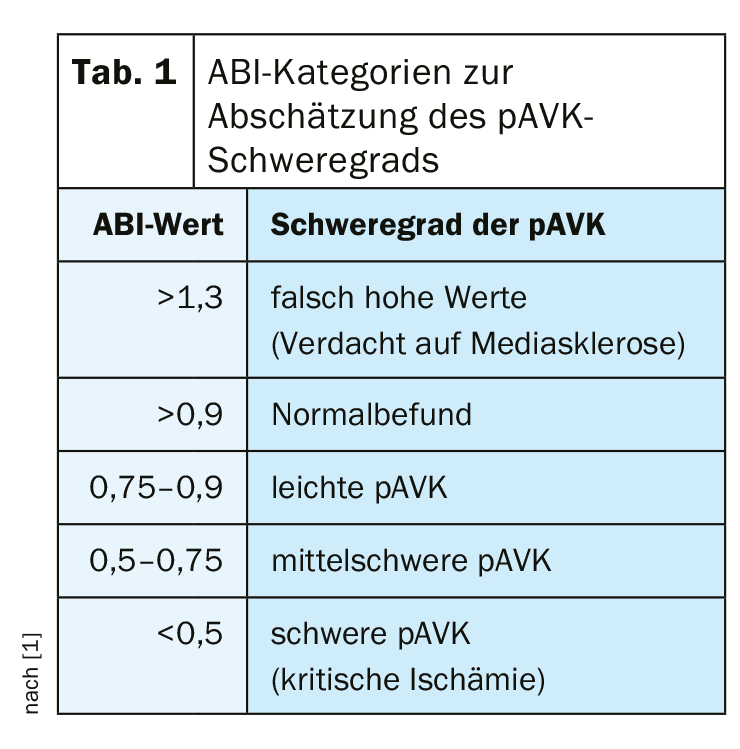

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (pAVD) is a lack of blood flow caused by vascular calcification, especially in the legs. Accordingly, it is often revealed by the presence of typical symptoms, such as pain when walking. A pAVD is present when the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is <0.9. Since this is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular risks must be assessed, treated, and eliminated. Especially patients with diabetes and a limited or suspended walking ability should be considered for the possibility of pAVD.

Initial assessment may include pathologic pulse palpation, flow sounds on auscultation, claudication, skin lesions, wounds, and pedal-emphasized rest pain. “However, 44% of all pathologic pulse findings are false, making it a poor predictor of the presence of pAVD,” explained Christoph Ploenes, MD, Düsseldorf, Germany. Reliably palpable foot pulses also speak against a clinically relevant pAVK. Furthermore, leg pain on walking is not sufficient to define claudication. Claudication is also not present if.

- the complaints persist when standing and walking,

- the leg pain is also present identically (especially laterally) when the patient is lying down,

- the pain occurs symmetrically on both sides depending on the posture.

Noninvasive instrumental examination methods, such as ABI measurement, step oscillogram, PW Doppler, or color duplex ultrasonography, should clarify what the hemodynamics of the arterial circulatory disturbance are and where the main localizations are. ABI values are used to classify severity (Table 1).

Safe therapy with paclitaxel-coated devices?

Stents and balloons coated with paclitaxel currently represent the most effective form of therapy in interventional vascular medicine. Meanwhile, 5-year studies confirm the continuing benefit of this treatment [2,3]. However, based on a meta-analysis, there were safety concerns regarding late toxicity and associated increased mortality, as reported by Prof. Thomas Zeller, MD, Bad Krozingen, Germany [4]. The BfArM has therefore asked the German Society of Angiology for a statement. The metanalysis was found to have fundamental weaknesses in its methodology. “There is ultimately no demonstrable causality between a paclitaxel-eluting intervention and increased mortality,” the expert acknowledged. However, the data is extremely thin and further investigation is urgently needed.

Effective anticoagulation in chronic pAVD.

According to the European guidelines, patients with symptomatic PAOD benefit from antiplatelet therapy in the long term [5]. The prognosis of patients with typical intermittent claudication is very good in terms of extremity-related morbidity. Only 1-2% of patients require amputation. Revascularization is needed by 30-40%. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, on the other hand, are a different story. After five years, 20% suffer a nonfatal event, and 10-15% die. Patients with critical limb ischemia already have a significantly worse 1-year prognosis. In 30%, amputation must be performed and about a quarter of patients die.

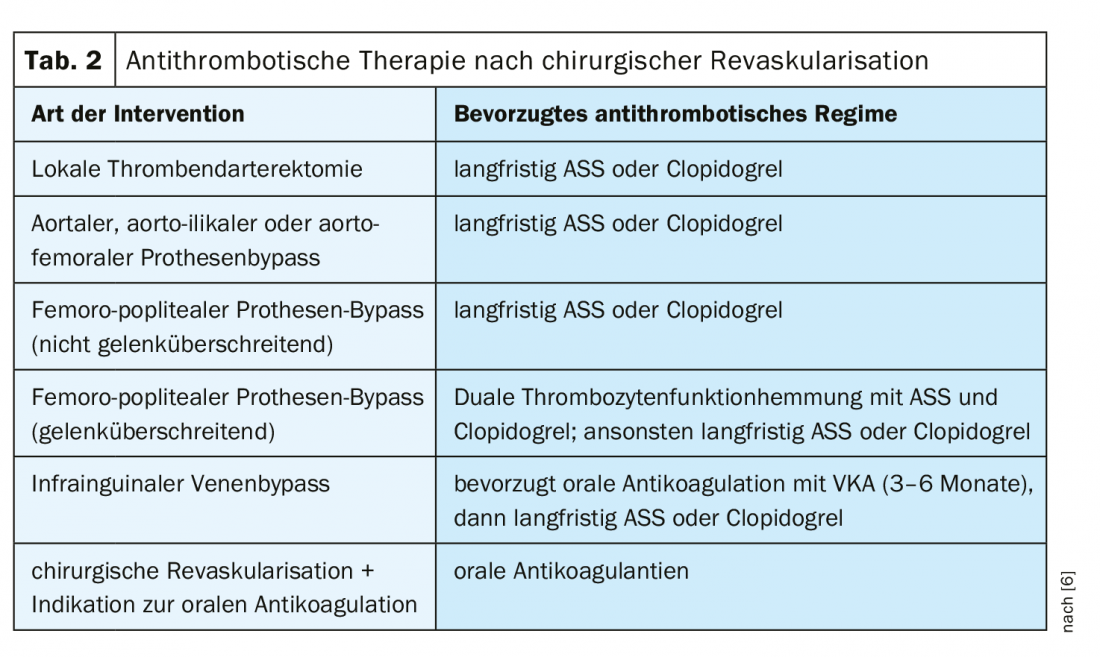

Basically, patients with pAVK have a higher baseline risk of MACE (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, apoplexy) than patients with myocardial infarction or apoplexy without pAVK. Accordingly, global cardiovascular risk should be reduced by means of platelet function inhibition. ASA or clopidogrel should be used in the first instance. In high-risk patients, a combination of ASA (100 mg) and rivaroxaban (2× 2.5 mg) should be considered. Patients with chronic pAVD should be treated with monotherapy using oral anticoagulants. After surgical revascularization, different antithrombotic regimens may be considered, depending on the type of intervention, as shown in Table 2.

Source: DGIM 2019, Wiesbaden (D)

Literature:

- S3 guideline on diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of peripheral arterial disease; www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/065-003l_S3_PAVK_periphere_arterielle_Verschlusskrankheitfinal-2016-04.pdf (last accessed June 23, 2019).

- Tepe G, et al: JACC CI 2018; 8: 102-108.

- Dake M, et al: Circulation 2016; 133: 1472-1483.

- Katsanos K, et al: J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7: e011245.

- Aboyans V, et al: ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases. European Heart Journal 2018; 9: 763-816.

- Gäbel, et al: MMW Fortschr Med 2016; 158: 52-55.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2019; 14(7): 25-26 (published 7/12/19, ahead of print)

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(4): 27