Little prevalent and difficult to grasp, fibromyalgia presents a challenge to many a physician. How can this diffuse disease be diagnosed? What therapeutic means are available?

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a syndrome characterized by chronic generalized pain in the muscles and muscle-tendon-bone junctions in combination with fatigue, rapid exhaustion, nonrestorative sleep, irritable bowel and bladder problems, depressed mood, or memory problems. The prevalence is 2-4% in industrialized countries, depending on studies, and slightly higher (5-15%) in general practice and clinical settings. Women are affected slightly more often than men (1-2 to 1). Prevalence increases with age, reaching a maximum at about 75 years of age and then declining slightly [1,2].

Unexplained cause

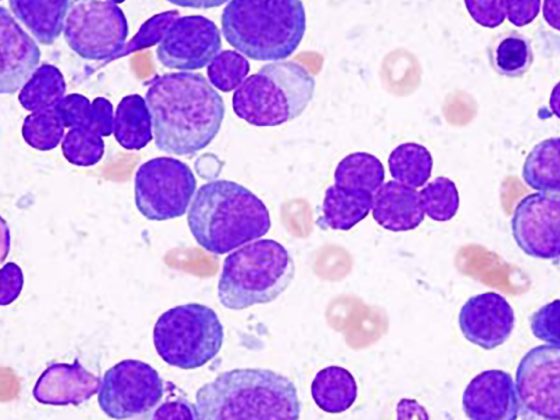

The cause of the FM remains unknown. Central and peripheral factors that may lead to the clinical picture are discussed. Central causes focus on the concept of central sensitization. This concept describes an increased sensitivity of the CNS in relation to pain perception and pain processing, which then often manifests itself in the clinically detectable phenomena of hyperpathia and allodynia. Further basic work has also shown that FM sufferers have neurotransmitter imbalances [3]. Thus, increased concentrations of substance P can be measured in the cerebrospinal fluid with simultaneously decreased levels of norepinephrine and serotonin. This may explain why even minor physiological stimuli can trigger a sensory overreaction. This phenomenon could be confirmed by fMRI imaging: FM showed increased activation of the pain matrix in response to “normal” nociceptive stimuli and decreased functional connectivity of descending pain-modulating structures [4]. Regarding peripheral mechanisms, recent research has focused on mitochondria and small unmyelinated peripheral C nerve fibers. Skin biopsies from FM patients showed significant dysfunction with respect to mitochondria with decreased bioenergetic levels and increased oxidative stress levels [5]. At most, these stress mechanisms play a role in the development of peripheral nerve damage. Lesions of peripheral C nerve fibers clinically result in altered temperature sensation and burning pain. This “small fiber neuropathy” was demonstrated by Üçeyler’s research group in 2013 [6] in biopsies and electrophysiological studies. Bioptically, skin biopsies of FM patients showed a reduced density of unmyelinated C-fibers, electrophysiologically, an increased temperature sensitivity with respect to cold or heat stimuli was detectable in combination with a reduced function of the small nerve fibers and their central afferents. Last, endocrinological disorders such as an altered (increased) stress response of the adrenal cortex-pituitary axis are also discussed in FM [7,8], which could also explain parts of the symptoms, especially the vegetative complaints.

Diagnostics

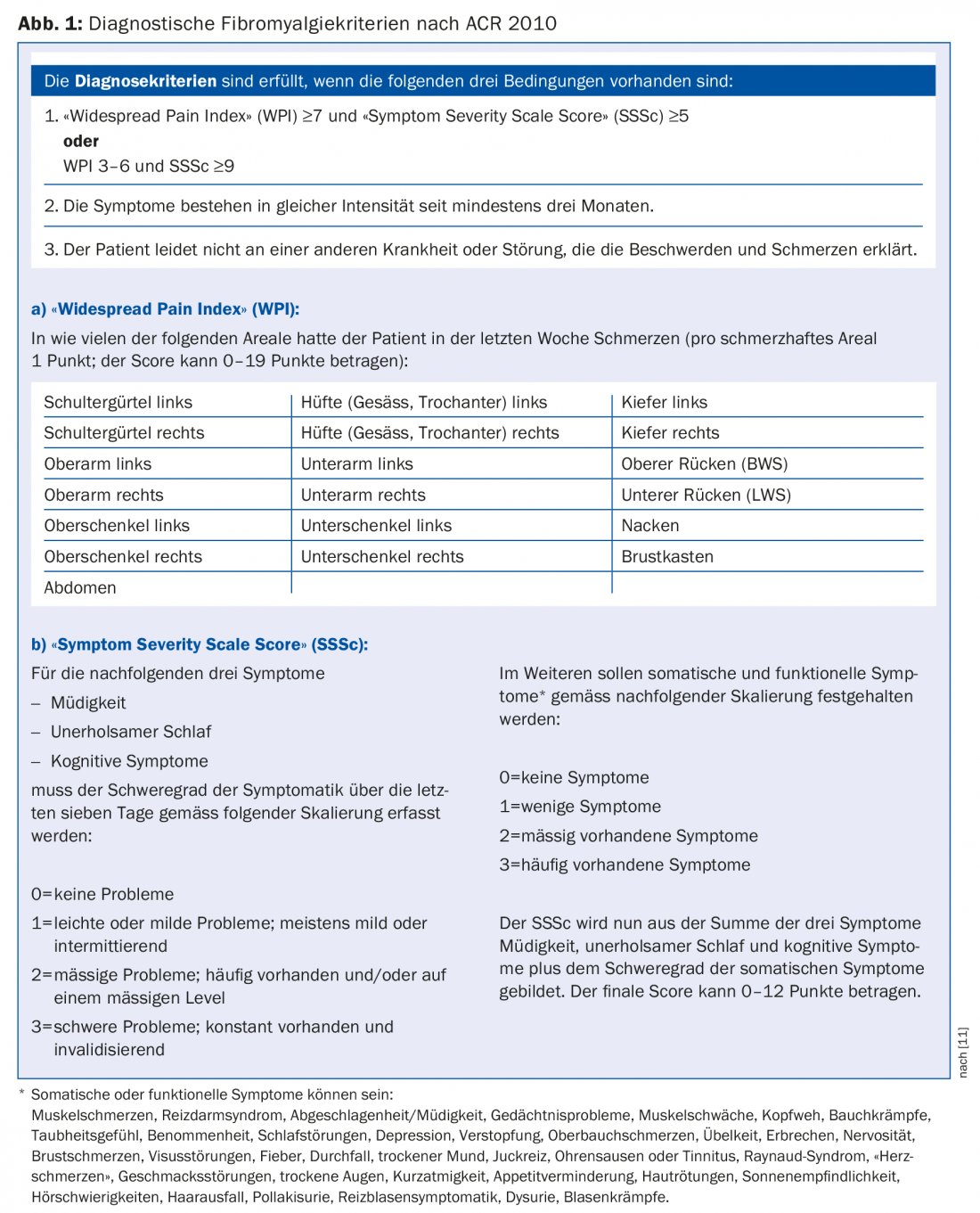

The ACR criteria published by Wolfe and colleagues in 1990 were used to classify fibromyalgia for over 20 years [9]. These well-known classification criteria combined anamnestic findings (three months of “whole body pain”) with clinical findings of the presence of so-called tender points (at least 11/18 defined tender points). With the application of these strict classification criteria, many patients who actually had the symptoms of FM were not classified as FM patients because, above all, the tender point limit was not reached, or the tenderness exceeded the defined criteria, or the pain was not “whole-body pain”. In 1998, modified FM classification criteria were published by Sprott [10], which assumed 24 tender points, with tender points in the hands, lower legs, and masticatory muscles defined in addition to the ACR criteria. In addition, control points were also defined in these classification criteria according to Sprott. It was also noted that whole-body pain on a VAS 0 to 10 had to be at least >5, and mandatory sleep disturbances had to be reported in addition to any other functional and autonomic symptoms that might be present. These FM classification criteria, adapted from Sprott, have unfortunately gained little acceptance, although they have been able to better describe and delineate the symptom picture of fibromyalgiaform whole-body pain. Finally, in 2010, new diagnostic criteria were presented by Wolfe and colleagues [11]. With these new criteria, Wolfe and colleagues abandoned the concept of tender points and instead added the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) to quantify whole-body pain. This score can vary from 0 to a maximum of 19 points. In addition, a symptom severity scale (“Symptom Severity Scale Score”, SSSc) was developed to graduate the severity of the three symptoms fatigue, non-restorative sleep and cognitive symptoms. Also to be scaled in this symptom severity scale are somatic symptoms such as muscle pain, irritable bowel or bladder symptoms, muscle weakness, headache, cramps, sensory deprivation and numbness, depression, stomach discomfort and nausea, and other somatic symptoms. The symptom severity score from these four items can range from 0 to 12 points.

An individual now meets these new diagnostic criteria for FM (Fig. 1) if he or she has a WPI ≥7 and an SSSc ≥5 or a WPI between 3 and 6 and an SSSc ≥9. In addition, the symptoms complained of must be consistently high (as before) for at least three months. In addition, the pain must not be explainable by another disorder or disease.

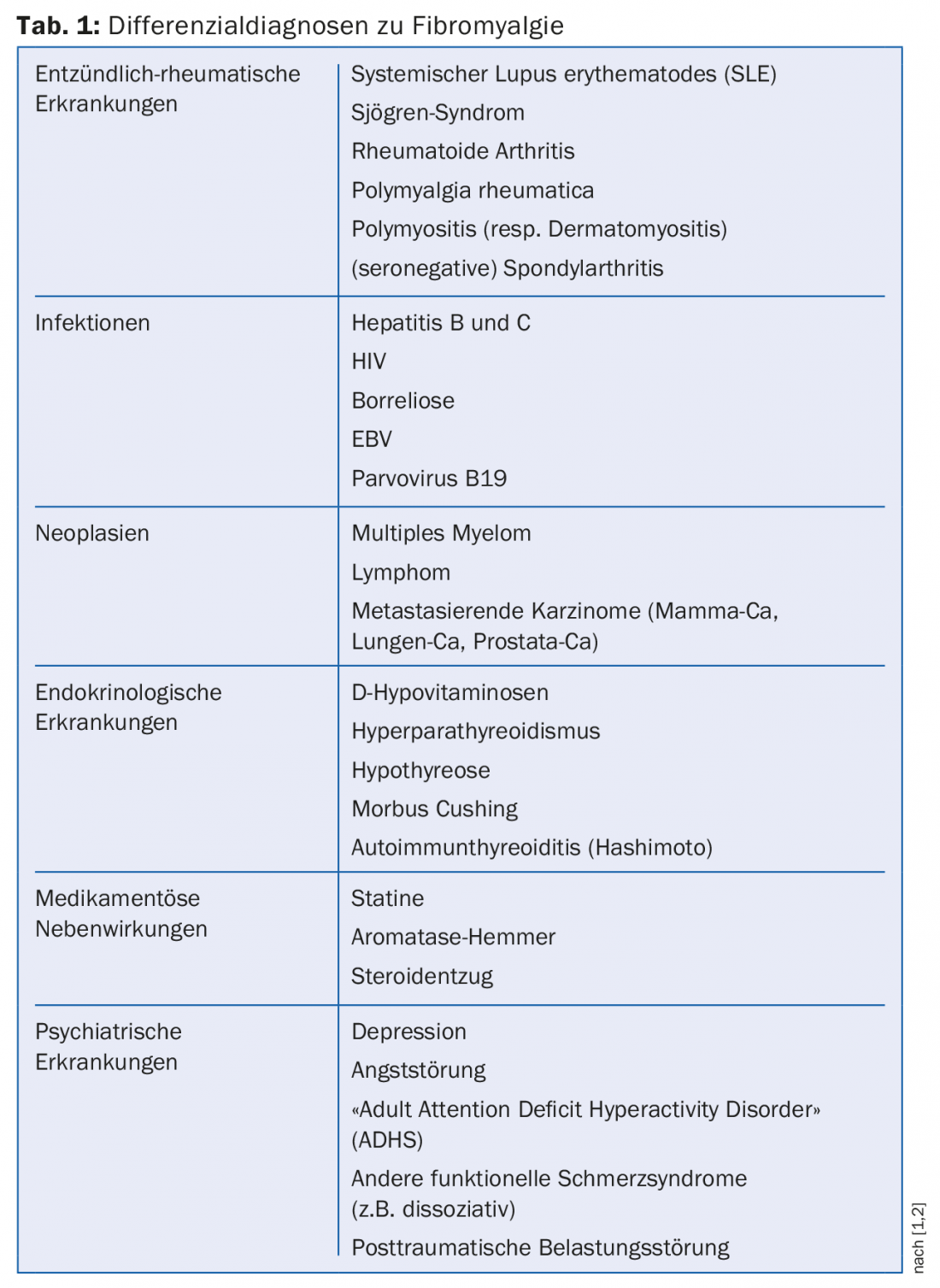

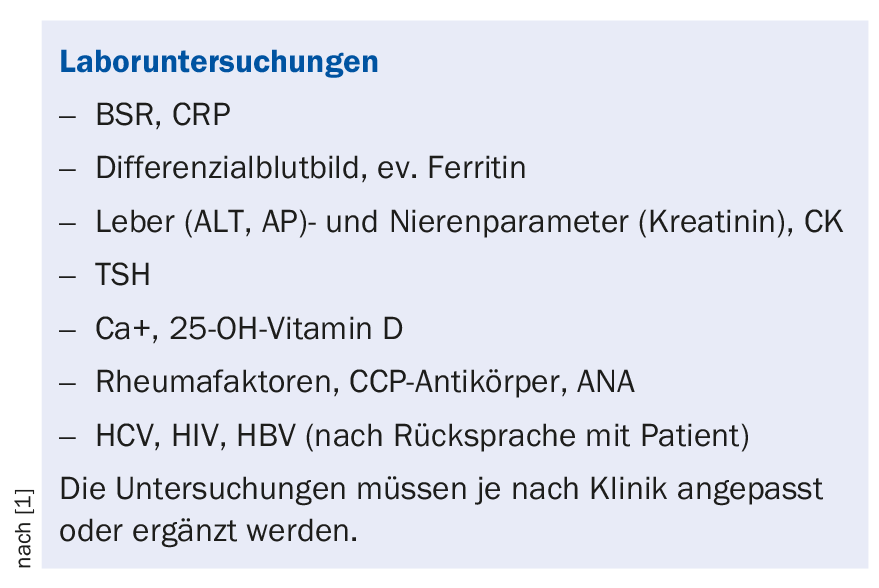

The diagnosis of FM can thus be made solely on the basis of a detailed record of the complaints by interviewing the patient. However, because the impairments for the patients in everyday life are sometimes considerable, the anamnesis must be supplemented by a precise social anamnesis and search for corresponding stress factors (work: dissatisfaction at work, emotional stress; household; leisure; partner relationship). In addition, a careful body status is indispensable in the clarification. However, the clinical examination is no longer intended to search for and diagnose “pain disease” by means of positive tender points. A thorough clinical examination as well as a complementary laboratory workup should identify other diseases and disorders that rule out FM and may be amenable to specific therapy. Possible differential diagnoses are summarized in table 1, and the recommended laboratory investigations are listed in the box.

Treatment with the involvement of the patient

Before initiating treatment, patients should be informed of the diagnosis [12]. From experience, it is very helpful if not only the diagnosis “fibromyalgia syndrome” is made, but also information about the pathophysiology is communicated to the affected persons. For example, a well-understood explanation is that FM is a mostly reversible functional disorder of central stimulus processing that can be well treated by self-management. Since many affected individuals fear serious illness, it is also important to reassure individuals that there is no serious illness or reduced life expectancy.

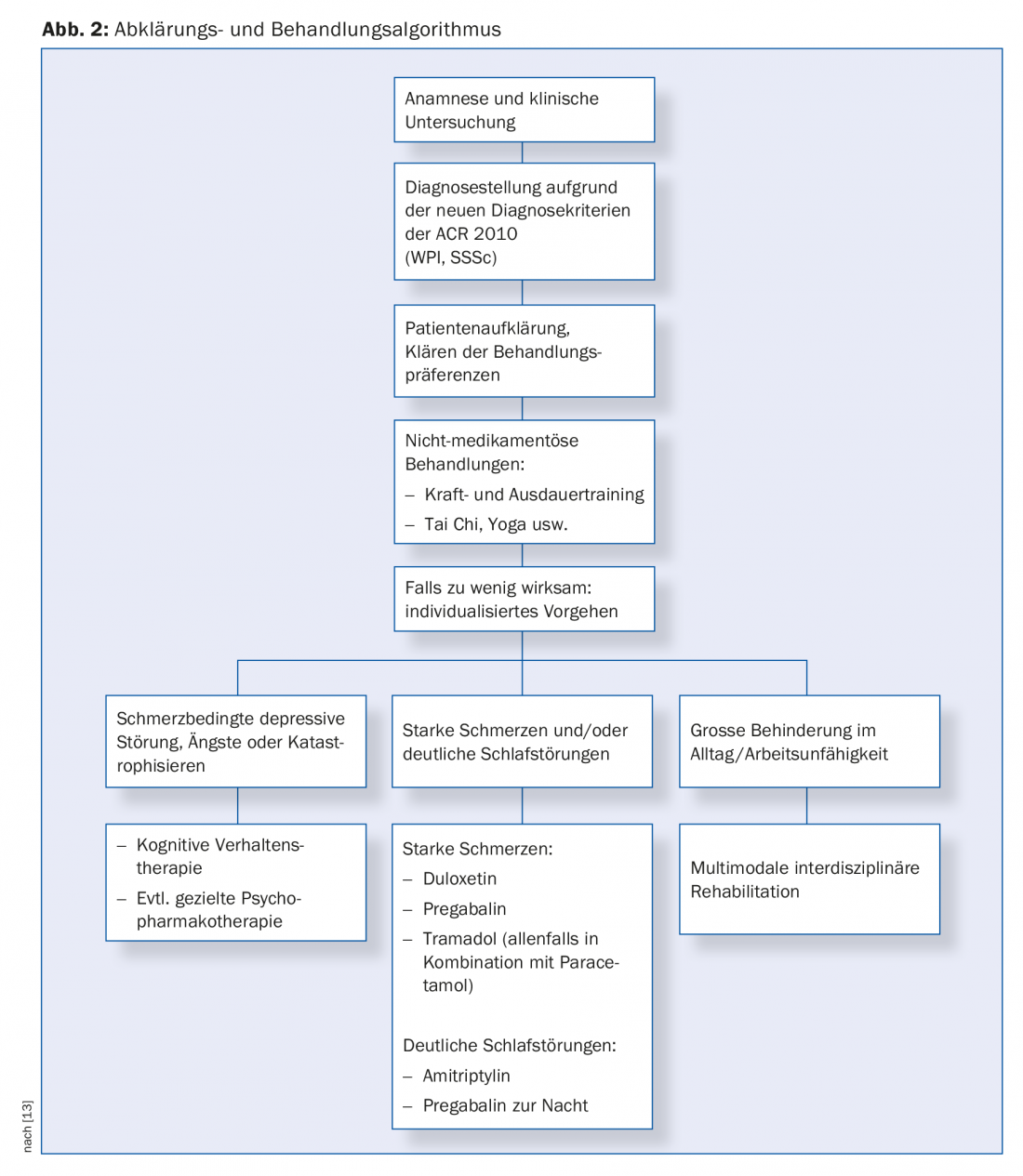

The actual treatment should then initially be based on non-drug measures. According to the latest EULAR treatment recommendations for FM from 2017 [13], aerobic endurance training and strength training have the best evidence in this regard. Cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture or qigong, tai chi and yoga are other recommended non-pharmacological treatment options. According to the 2017 German Guidelines [12], it is also very useful to consider patient preferences and any comorbidities when selecting treatment procedures. Only if patients are also happy to undergo treatment or are able to do so despite comorbidities, is the necessary adherence to treatment measures given. In severe cases, multimodal inter- and transdisciplinary rehabilitation is also useful when disability is imminent.

Medication helpful are dual-acting analgesics, primarily tramadol (or briefly tapentadol), amitriptyline in low doses (25-75 mg at night), the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine (30-60 mg/day), or pregabalin. All other medications (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are not recommended. Useless – and thus not indicated in the treatment of FM – are corticosteroids, classical sedatives (benzodiazepines), neuroleptics or opiates, unless a comorbidity justifies the use of these drugs. Figure 2 graphically summarizes the treatment options.

Take-Home Messages

- Fibromyalgia is a polyetiologic disorder of unclear origin. Central and peripheral mechanisms are discussed in pathophysiology.

- Diagnosis is based on the revised 2010 ACR definition criteria. A careful clinical examination including a laboratory work-up is obligatory if fibromyalgia is suspected in order to identify other causes for the symptoms described.

- Once the diagnosis of fibromyalgia is confirmed as far as possible, patients should be educated about their condition, including the possible pathophysiological causes.

- Non-drug treatments should be provided in the first instance.

- Medication options include tramadol, amitryptyline, duloxetine, or pregabalin.

Literature:

- Aeschlimann A, et al: Fibromyalgia syndrome: new insights into diagnosis and therapy, part 1: clinical picture, background and course. Schweiz Med Forum 2013; 13(26): 517-521.

- Aeschlimann A, et al: Fibromyalgia syndrome: new insights into diagnosis and therapy, part 2: practical approach to assessment and treatment. Schweiz Med Forum 2013; 13(27-28): 541-543.

- Ablin JN, Buskila D: Update on the genetics of the fibromyalgia syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015; 29(1): 20-28.

- Cagnie B, et al: Central sensitization in fibromyalgia? A systematic review on structural and functional brain MRI. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 44(1): 68-75.

- Sanchez-Dominguez B, et al: Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and, inflammation common events in skin of patients with Fibromyalgia. Mitochondrion 2015; 21: 69-75.

- Üçeyler N, et al: Small fiber pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain 2013; 136(6): 1857-1867.

- Demitrack MA, Crofford LJ: Evidence for and pathophysiologic implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998; 840: 684-697.

- Spaeth M, Rizzi M, Sarzi-Puttini P: Fibromyalgia and sleep. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25(2): 227-239.

- Wolfe F, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33(2): 160-172.

- Sprott H, Muller W: Functional Symptoms in Fibromyalgia: Monitored by an Electronic Diary. Clin Bull Myofascial Ther 1998; 3: 61-67.

- Wolfe F, et al: The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62(5): 600-610.

- Petzke F, et al: [General treatment principles, coordination of care and patient education in fibromyalgia syndrome : Updated guidelines 2017 and overview of systematic review articles]. Pain 2017; 31(3): 246-254.

- Macfarlane GJ, et al: EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(2): 318-328.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(12): 15-19