Anaphylaxis is life-threatening. Nevertheless, less than 20% receive the only adequate therapy: epinephrine. Therefore, if in doubt, act correctly and inject epinephrine immediately intramuscularly by auto-injector!

Dinner at acquaintances, the children drink cold milk. Suddenly, a 16-year-old boy feels sick, vomits, can’t breathe, and collapses….

Anaphylaxis is a medical emergency that usually occurs unexpectedly and yet must be recognized and treated quickly. It is the most severe and threatening hypersensitivity reaction that affects the entire body and can lead to anaphylactic shock. After contact with the triggering substance, e.g. milk, an acute systemic reaction occurs suddenly and unexpectedly in several organ systems: a life-threatening condition. In some sensitized individuals, tiny amounts of an allergen are enough to cause anaphylaxis, but not all people with allergies have an anaphylactic reaction [1,2].

Pathogenesis

The pathomechanism is immunologically mediated via IgE antibodies. During this process, vasoactive substances are released from mast cells and basophils. Vasodilation, smooth muscle contraction, and complement activation are the consequences that explain the symptoms in the affected organ systems. Rarely, non-IgE-dependent immune mechanisms trigger anaphylaxis. This is called a pseudoallergic reaction but shows comparable clinical symptoms [1].

Augmentation factors

Augmentation factors play a lesser role in childhood. This changes with increasing age, showing an increasing correlation in adolescents and adults. The response threshold is lowered during physical exertion, emotional stress, acute infections, use of painkillers (NSAID), menstruation and alcohol consumption [1–5]. Risk factors for severe anaphylactic reactions include existing and especially inadequately treated bronchial asthma, a history of anaphylaxis, marked atopic dermatitis, and mastocytosis [1–5].

Warning signs and symptoms

Subjective symptoms and warning signs of anaphylaxis may include: Sensations in the mouth and throat such as itching, tingling and burning, scratching in the throat with coughing, clearing the throat or grunting, itching on the hands, feet, behind the ears or in the genital area, nausea, headache as well as abdominal pain, anxious restlessness, dizziness, weakness and sometimes sweating. Preschoolers who are poor at reporting their symptoms are notable for general restlessness, malaise, withdrawal behavior, and denial or aggression.

Clinical symptoms of life-threatening reactions in children and adolescents are predominantly obstructive respiratory symptoms [4]. Upper respiratory symptoms include dysphagia with salivation, cloggy speech, or inspiratory stridor as signs of laryngeal edema, swelling of the tongue or uvula. In the lower airways, bronchoconstriction leads to dyspnea with wheezing, prolonged expiratory flow, and use of respiratory support muscles. Here, the severity of asthma correlates directly with that of the anaphylactic reaction.

Anaphylaxis characteristically manifests itself with the sudden appearance of symptoms on the skin, digestive tract, respiratory tract and circulatory system. A severe reaction in the sense of anaphylaxis is only present if at least two organ systems are affected. The symptoms of anaphylaxis vary greatly from person to person and even in repeated cases. They may be mild or pronounced, single or combined, simultaneous or sequential, progressing acutely at any time, but may also stop at any stage. This is what makes assessment in the acute incident so difficult, and so severity classification is usually done retrospectively.

Assessment of anaphylactic reaction

A recent article addresses this issue and addresses the difficulty of objectively standardizing severity of allergic reaction for the various triggers such as insect stings, foods, and drugs. Parents tend to perceive a sudden skin reaction as more dramatic (because it is immediately visible externally) than the much more serious symptom, respiratory distress, which is more difficult to perceive. This may be because the cough or whistling breath sounds are not unusual symptoms for affected parents, who have often known them to be less threatening due to infections. Similarly, gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea or vomiting. Therefore, a simple scoring system is needed that quickly assesses the threat of airway involvement and then leads to rapid and effective treatment [6]. The “Christine Kühne Center for Allergy Research and Education” (CK-CARE) in Davos has published a leaflet on anaphylaxis: “Anaphylaxis – Acting in an emergency”, which serves well in the family practice. The fact sheet helps to recognize anaphylaxis more quickly by distinguishing only three clinical manifestations – grouped by symptoms. Emergency management of anaphylaxis and the effects of emergency medications are illustrated using a timeline (www.ck-care.ch/merkblatter).

Epidemiology

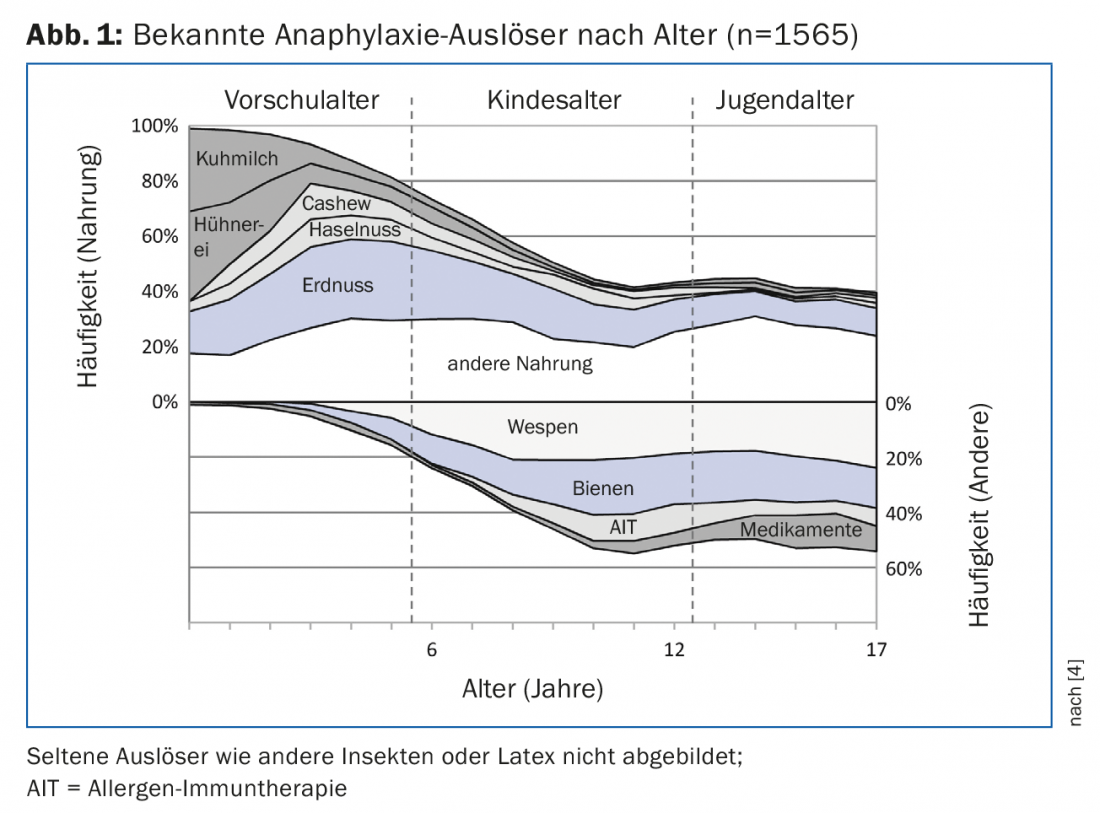

Exact data on the frequency of anaphylaxis do not exist because there is no binding definition and anaphylaxis is not reportable. For Switzerland, the incidence is estimated at 10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. A fatal outcome is nevertheless very rare and corresponds to a similar risk of becoming a victim of homicide [3]. An anaphylaxis registry (anaphylaxie.net) has been maintained for Germany, Austria, and Switzerland for more than ten years. In the period from July 2007 to March 2015, 1970 patients under 18 years of age with anaphylactic reactions were identified [4]. The registry shows that by far the most common triggers of anaphylaxis in childhood are food (66%), followed by bee or wasp stings (19%), and much less frequently medications (5%) (Fig. 1) [4]. In terms of food, peanut leads, followed by cow’s milk, hen’s egg, cashew and hazelnuts. Among medications, it is surprising that analgesics trigger reactions twice as often as antibiotics in predominantly affected adolescents and are about as common as reactions after desensitization [4]. In adulthood, the order changes, and the most common triggers of anaphylaxis are then insect venoms, followed by drugs and food. In this context, the risk of a severe reaction increases with age and in the case of mastocytosis [3–5].

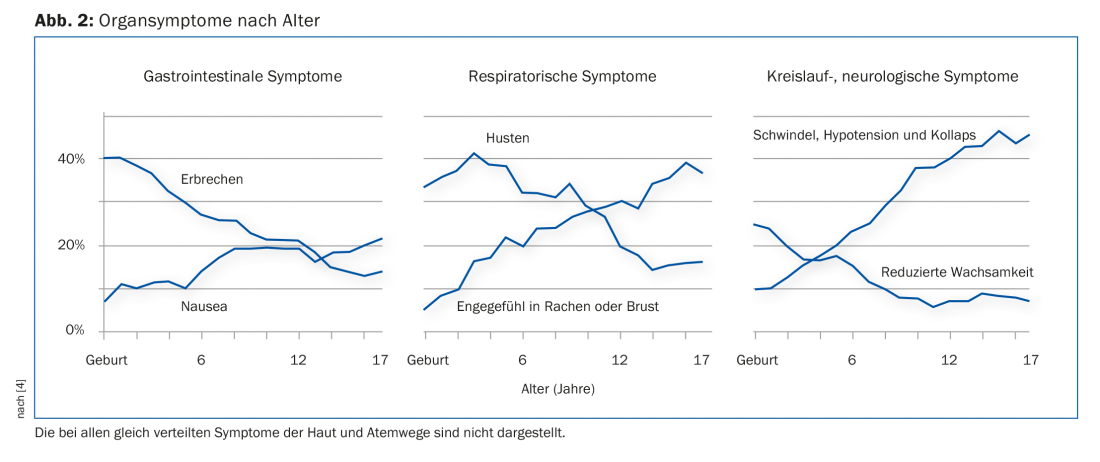

The skin was affected in almost all children and adolescents (92%). Among these, the following specific skin symptoms were similarly distributed across all age groups: Angioedema (53%), Urticaria (62%), Pruritus (37%), and Erythema/Flush (29%). The respiratory tract was also involved in 80% of patients. Dyspnea was reported by 55%, and obstructive airway symptoms were documented as whistling breathing in 35% regardless of age.

Figure 2 shows organ symptoms by age [4].

Allergen exposure: locations and reaction time

Most incidents occurred at home (46%), outdoors on the road (19%), in kindergarten or school (9%), in doctors’ offices or hospitals (9%), and less frequently in restaurants (5%). The duration between allergen exposure and onset of symptoms was mostly less than ten minutes (58%), but 8% reported a delayed reaction after more than one hour. 5% showed a biphasic course with a second reaction after more than twelve hours. Treatment was provided by laypersons in 30%, and only 10% performed self-treatment. 70% sought professional medical help [4].

Diagnostics

The diagnosis is derived from the course of the reaction, the symptoms of the organ systems involved, and the patient’s history. In the context of the anaphylactic reaction, therefore, the skin and mucous membrane symptoms (eyes, lips, throat), the gastrointestinal complaints (vomiting, nausea), the impairment of the respiratory tract (laryngeal or bronchial obstruction), the circulatory situation (pulse and blood pressure) and the state of consciousness must be recorded in particular. When clarifying an anaphylactic reaction, specific questions should be asked about possible triggers and associated concomitant circumstances (augmentation factors). An allergological diagnosis with determination of specific IgE antibodies is indispensable and should, if possible, be performed by an allergist specialized in children and adolescents, since diagnostics based on allergen components and their interpretation have become increasingly complex and require a certain expertise.

Therapy of acute anaphylactic reaction

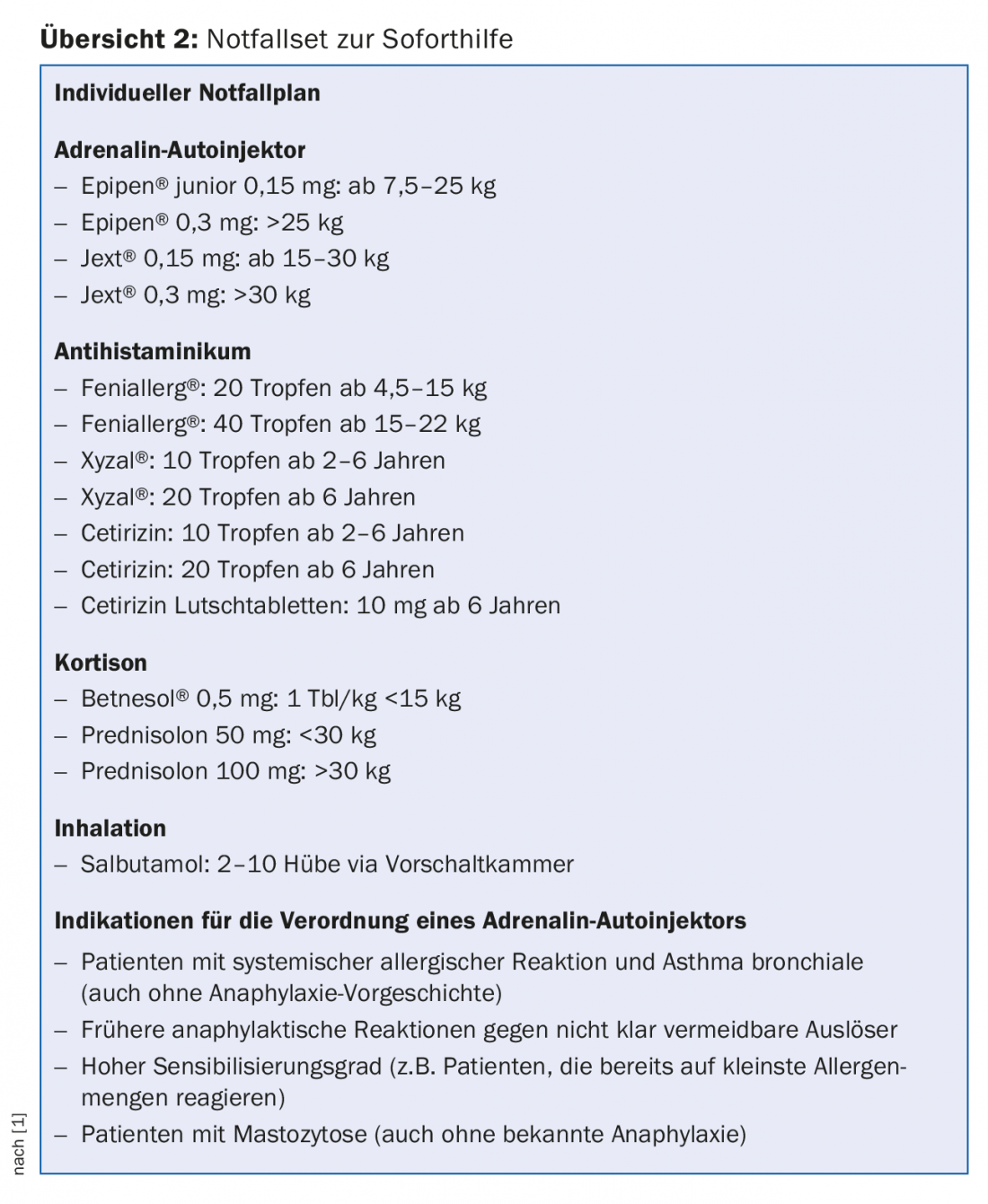

The most important drug in the acute therapy of anaphylaxis is adrenaline, as it affects all organ systems involved. Only epinephrine is able to rapidly and effectively antagonize the pathomechanisms of anaphylaxis. It leads to bronchodilation, vasoconstriction, edema reduction, decrease in vascular permeability and positive inotropy at the heart. There is no absolute contraindication for severe life-threatening anaphylaxis [1,7].

Using an epinephrine auto-injector, it can be easily administered intramuscularly by physicians and laypersons. However, it is still too rarely used by patients and physicians [4,7–9]. The reason seems to be that the potentially life-threatening course of anaphylaxis is underestimated and the effect of antihistamines and cortisone is overestimated. In addition, there is the unjustified fear of the side effects of an adrenaline injection – in parents also the fear of the injection needle and of hurting their own child with it [3,8,9]. In urban settings, therefore, people are more likely to take the risk of driving to the emergency department or calling an ambulance rather than treating themselves [4]. If only antihistamines and cortisone are administered in the emergency room instead of epinephrine, this reinforces the assumption that epinephrine is not necessary for the treatment of anaphylaxis. In some cases, patients in the emergency room already feel better and show fewer symptoms because the body has naturally released adrenaline due to stress or because the antihistamine still administered at home is beginning to take effect [3,8].

All evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of anaphylaxis worldwide recommend immediate intramuscular administration of epinephrine [1-3, 7-9] Yet it is administered in less than 20% of documented anaphylactic reactions. Antihistamines and cortisone are most commonly given [4,7]. However, pharmacokinetics show that even a fast-acting antihistamine takes more than 25 minutes to take effect, and cortisone takes as long as 60 minutes to exert its effect [7]. In an emergency, however, the effect of the administered drug should begin within five minutes, otherwise the designation “emergency drug” is misleading, dangerous and simply not life-saving.

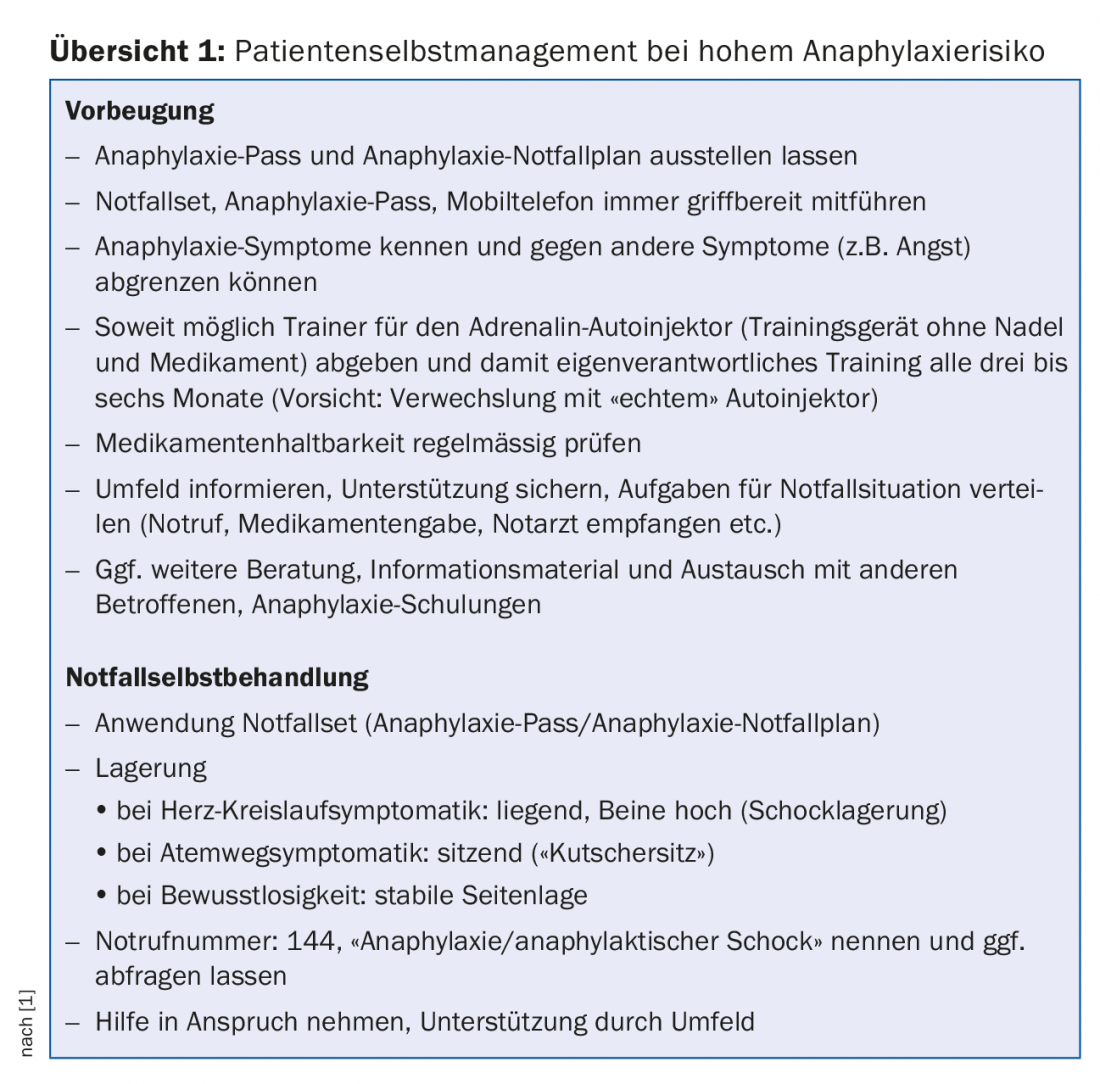

One third of all affected children had a history of anaphylaxis and 70% knew to which allergen they were reacting [4]. The potential risk of recurrence can lead to marked anxiety with restrictions on daily activities and anxiety disorders and thus overprotection on the part of parents [3,9]. For this purpose, coaching with information transfer is indispensable [9]. Patients, their parents, and caregivers in kindergarten or school must be instructed on how to avoid anaphylaxis triggers and how to administer emergency medications. When an emergency kit is deposited in the nursery or school, caregivers must practice and master its proper use. Training programs for patients with anaphylaxis have been developed for this purpose.

Anaphylaxis Emergency Kit

All anaphylaxis patients must be equipped with an emergency kit and emergency plan (overview 1 and 2) consisting of epinephrine autoinjector, antihistamine, cortisone and inhalation spray if necessary [1,2]. On the personal anaphylaxis emergency plan, the potential triggers of an allergic reaction as well as the required therapy with instructions for action should be clearly visible at first glance (“Anaphylaxis emergency plan for children and adolescents” at www.ck-care.ch/merkblatter).

The handling of the epinephrine auto-injector must be carefully practiced. As a family doctor, it is best to have the parents show you how it is used on the child. Here is a personal anecdote: When I once demonstrated the use of the adrenaline auto-injector, I accidentally took the previously presented and confusingly similar real Epipen® from the table instead of the Trainer-Epipen® and injected it with full force into my thigh. Within a minute, I got a red head, felt hot flashes, and was a little hyper. The effect subsided again after about ten minutes. The teenager and his mother were impressed and will now certainly use the Epipen® more generously in an emergency. Unfortunately, for the youngster described at the beginning, the saving injection came too late. Since there was no improvement by inhalation and therefore epinephrine was administered with delay, he died. He had also previously had repeated reactions to milk as a child [4].

An information sheet “First aid in case of an anaphylactic reaction” can be found on the Website of aha! Allergy Center Switzerland.

Take-Home Messages

- Anaphylaxis is rare in the general population but is life-threatening.

- One third of those affected have had a previous anaphylactic reaction and know the trigger.

- Less than 20% receive the only adequate therapy: epinephrine.

- Unfortunately, some patients receive this first aid too late, with fatal results.

- If in doubt, do not wait but act and inject adrenaline immediately intramuscularly by auto-injector!

Literature:

- Ring J, et al: Guideline for acute therapy and management of anaphylaxis. Allergo J Int 2014; 23: 96-112.

- Muraro A, et al: Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy 2014; 69(8): 1026-1045.

- Turner PJ, et al: Fatal anaphylaxis: mortality rate and risk factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017; 5(5): 1169-1178.

- Grabenhenrich LB, et al: Anaphylaxis in children and adolescents: The European Anaphylaxis Registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137(4): 1128-1137.

- Worm M, et al: Factors increasing the risk for a severe reaction in anaphylaxis: An analysis of data from The European Anaphylaxis Registry. Allergy 2018; 73(6): 1322-1330.

- Muraro A, et al: The urgent need for a harmonized severity scoring system for acute allergic reactions. Allergy 2018. DOI: 10.1111/all.13408 [Epub ahead of print].

- Song TT, Worm M, Liebermann P: Anaphylaxis treatment: current barriers to adrenaline auto-injector use. Allergy 2014; 69(8): 983-991.

- Chooniedass R, Temple B, Becker A: Epinephrine use for anaphylaxis: Too seldom, too late: current practices and guidelines in health care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017; 119(2): 108-110.

- Kastner M, Harada L, Waserman S: Gaps in anaphylaxis management at the level of physicians, patients, and the community: a systematic review of the literature. Allergy 2010; 65(4): 435-444.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(8): 15-19

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(5): 20-24