Diabetics are more likely to be affected by heart failure than non-diabetics. Their prognosis is significantly worse. What are the pharmacotherapeutic features to be considered in diabetic patients with heart failure?

The often unspecific manifestations of symptoms such as fatigue, tiredness, exhaustion and shortness of breath do not always make early detection of heart failure easy. With concomitant diabetes mellitus, some of these complaints may even be misinterpreted as diabetic sequelae. One reason for the simultaneous presence of these two diseases may be the underlying pathomechanisms. The metabolic syndrome that often accompanies type II diabetes mellitus carries risk factors for heart failure, including the possible complication of hypertension, dyslipidemia, or obesity. However, heart failure is also discussed as a direct consequence of diabetes. Epicardial and intramyocardial fat deposition and inflammatory signals appear to be among the metabolic changes here.

Definition of heart failure

Patients with heart failure can be classified into HFrEF (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction), HFmrEF (heart failure with intermediate ejection fraction), and HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) using the European Society of Cardiology guidelines [2]. Classification is primarily based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, <40%, 40-49%, and ≥50%). In addition, the serum concentration of natriuretic peptides and other criteria such as the presence of additional systolic dysfunction are taken into account (table 1) . The clinic in terms of NYHA stages I-IV remains the decisive factor in determining the therapeutic approach.

Heart failure and diabetes

The numbers concerning the presence of heart failure in diabetes have long been underestimated. However, studies show that the incidence of heart failure is higher in diabetics than in non-diabetics in any age group [3]. This worsens the prognosis. Heart failure mortality is also higher in diabetic patients than in patients who do not have such a metabolic disorder [4]. More recent data from the PARADIGM-HF trial confirm these findings and show that approximately one in five patients with diabetes and heart failure die after 2.5 years [5].

Heart failure therapy

An overview of the therapeutic regimen in the presence of HFrEF (symptomatic patient with LVEF <40%) can be found in the European Guideline [2] (for therapy of HFrEF, see Cardiovasc 2018; 3: 29-32). ARNI (angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor) was added to the therapy regimen as a relatively new substance group. The enzyme neprilysin degrades natriuretic peptides, which counteract the mechanisms of development of heart failure by acting as an antagonist to the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. The breakthrough study (PARADIGM-HF) shows that this class of agents is significantly superior to enalapril in reducing cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization in heart failure patients [6].

In addition to ARNIs, classical drug agents (ie, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, AT1 blockers, mineral corticoid rec. antagonists) also improve the prognosis of HFrEF, as shown by studies [7,8]. No specific data are available for patients with diabetes, but subgroup analyses suggest that the proven effects may also be assumed for this patient group [9]. Thus, heart failure therapy does not differ in patients with and without diabetes.

Therapy of diabetes in patients with heart failure

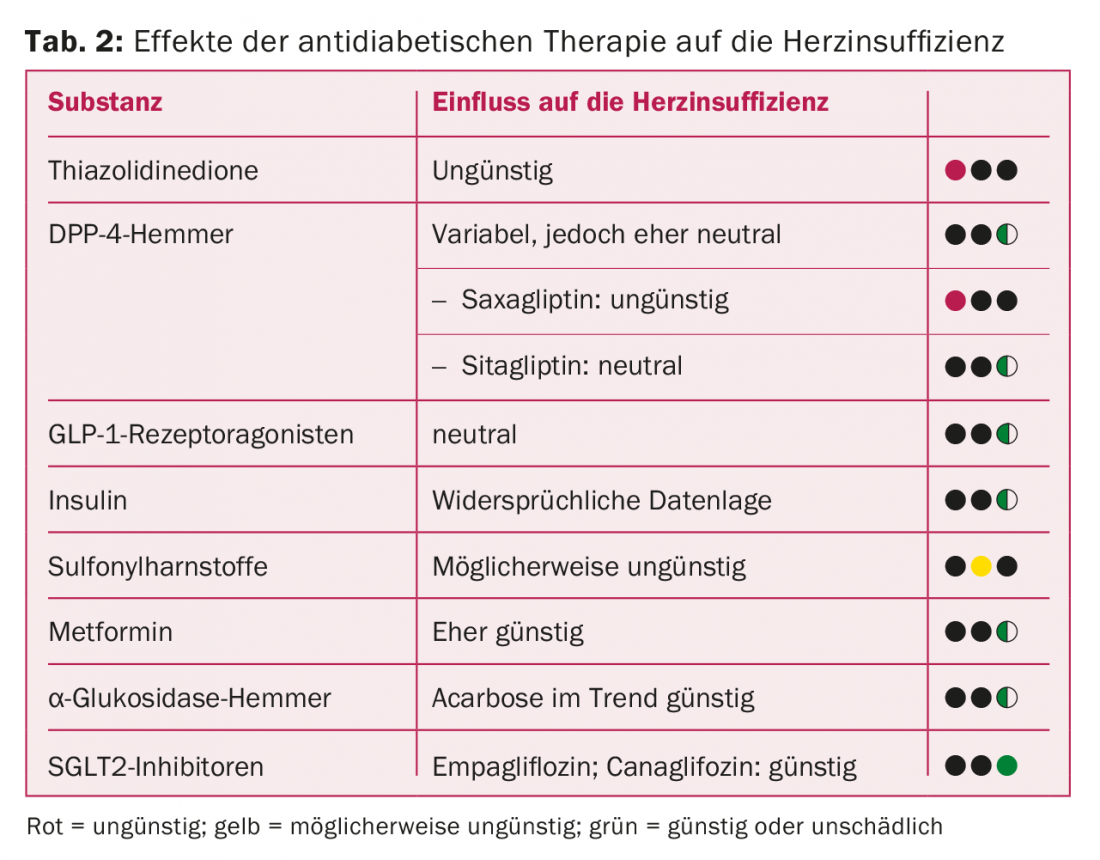

An overview of the influence of diabetic therapy on existing heart failure is provided in Table 2.

Thiazolidinediones lead to fluid retention and increased cardiac decompensation in preexisting heart failure via improvement of insulin sensitivity, resulting in increased hospitalization.

There are mixed data on DPP-IV inhibitors. In the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial, an increased heart failure-related hospitalization rate occurred with saxagliptin [10]. This could not be confirmed for sitagliptin [11]. Therefore, a substance effect and not a class effect of DPP-IV inhibitors can be assumed.

Conflicting results are available on the influence of insulin. In a retrospective cohort study, risk factors for the development of heart failure were investigated in >8000 diabetic patients. These older data show a 25% increased risk with the use of insulin [3]. In contrast, the large randomized ORIGIN trial found no increased risk of heart failure with the use of insulin glargine [12]. The questionable bias of retrospective studies and the good evidence of large randomized trials therefore suggest that insulin is rather not harmful in this context.

Various retrospective studies are available on the group of sulfonylureas, suggesting that this substance group has a rather unfavorable effect. Compared with metformin, for example, an increased risk of heart failure was found [13].

According to Prof. Marx, further data on sulfonylureas will follow the completion of the ongoing CAROLINA trial, which compares sulfonylureas with linagliptin in type II diabetics [14].

Source: Diabetes Congress, May 9-12, 2018, Berlin (D).

Literature:

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Diabetes. www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/gesundheitszustand/krankheiten/diabetes.html, accessed July 17, 2018.

- Ponikowski P, et al: 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016; 37(27): 2129-2200.

- Nichols GA, et al: The incidence of congestive heart failure in type 2 diabetes: an update. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(8): 1879-1884.

- Gustafsson I, et al: Influence of diabetes and diabetes-gender interaction on the risk of death in patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure. JACC 2004; 43(5): 771-777.

- Kristensen SL, et al: Risk Related to Pre-Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetes Mellitus in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: Insights From Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure Trial. Circ Heart Fail 2016; 9(1): pii: e002560.

- McMurray JJ, et al: Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(11): 993-1004.

- MERIT-HF Study Group: Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999; 353(9169): 2001-2007.

- Zannad F, et al: Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(1): 11-21.

- Haas SJ, et al: Are beta-blockers as efficacious in patients with diabetes mellitus as in patients without diabetes mellitus who have chronic heart failure? A meta-analysis of large-scale clinical trials. Am Heart J 2003; 146(5): 848-853.

- Scirica BM, et al: Heart failure, saxagliptin, and diabetes mellitus: observations from the SAVOR-TIMI 53 randomized trial. Circulation 2014; 130(18): 1579-1588.

- Green JB, et al: Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(3): 232-242.

- ORIGIN Trial Investigators, et al: Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(4): 319-328.

- McAlister FA, et al: The risk of heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with oral agent monotherapy. Eur J Heart Fail 2008; 10(7): 703-708.

- Marx N, et al: Design and baseline characteristics of the CARdiovascular Outcome Trial of LINAgliptin Versus Glimepiride in Type 2 Diabetes (CAROLINA®). Diab Vasc Dis Res 2015; 12(3): 164-174.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(4) – published 7/19/18 (ahead of print).