Stress incontinence is addressed surgically, whereas overactive bladder is primarily addressed with medication. If conservative measures are unsuccessful, urogynecological and urodynamic clarification should be performed.

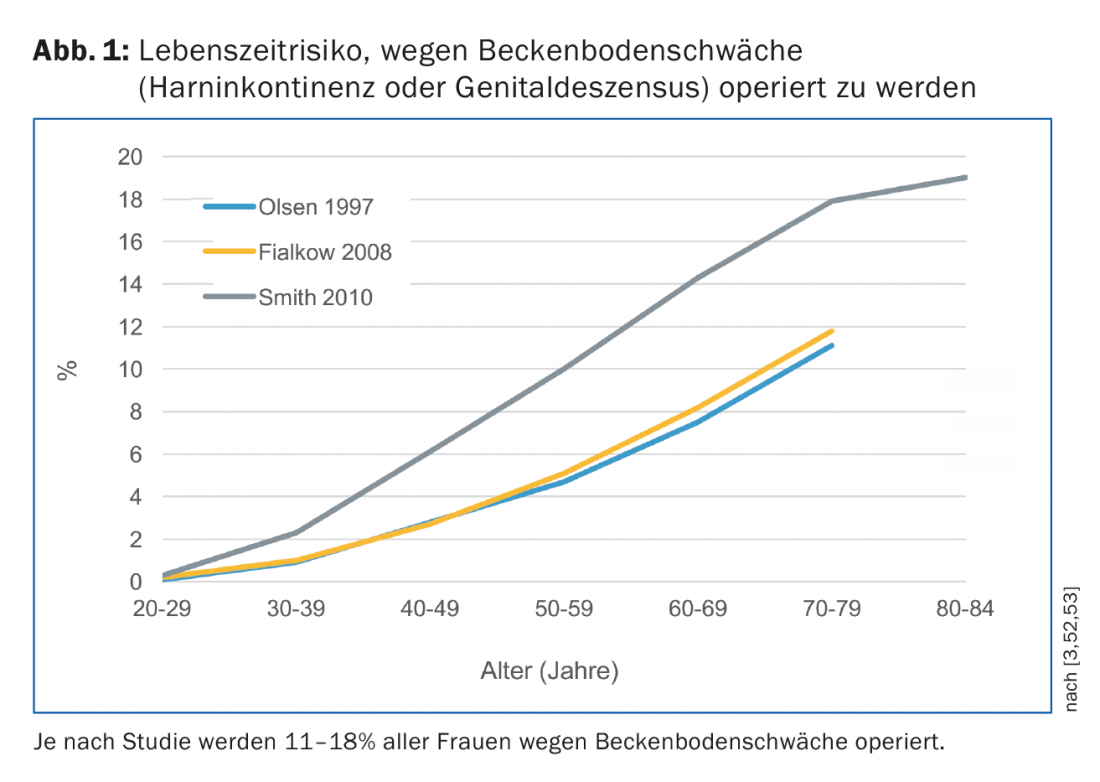

Urinary incontinence affects people of all ages, but shows an age-related increase in prevalence [1,2]. In the Western world, this is between 24% and 45%. In Switzerland, according to the 2012 Swiss Health Survey by the Federal Statistical Office, one in ten women “sometimes have difficulty retaining water” and require surgery for urinary incontinence or genital descensus (lowering or protrusion of the vagina or uterus) by age 80 ( Fig. 1) [3].

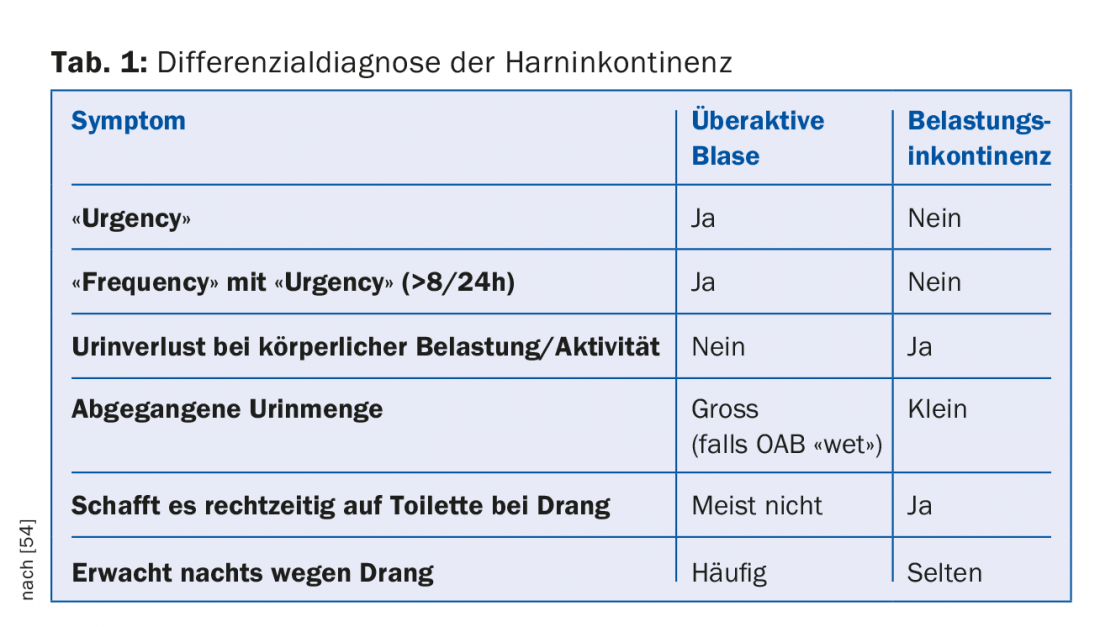

The definition of urinary incontinence is “any involuntary loss of urine” [4]. If this occurs synchronously with physical activity such as coughing, sneezing or laughing, it is referred to as stress urinary incontinence (SUI). If patients suffer from an imperative, difficult-to-suppress urge to urinate, typically accompanied by “frequency” (frequent urination) and nocturia (nocturnal urination), they have overactive bladder syndrome (OAB; older terms “irritable bladder” or “urge incontinence”); one third are incontinent, two thirds are continent (OAB “wet” or OAB “dry” or dry). The distinction between stress incontinence and OAB is important because the therapeutic approaches are different: While stress incontinence can be remedied surgically, OAB is primarily addressed with medication. Almost one third have pure stress incontinence and one quarter pure OAB (according to the patients of our special urogynecology consultation at the University Hospital Zurich with an average age of 58.5 years). In everyday clinical practice, almost every second person affected has a combination of both forms of incontinence (mixed incontinence), which makes treatment more difficult and reduces success. Neurological diseases, fistulas or polyneuropathic overflow incontinence in diabetes mellitus are examples of other rare forms of incontinence.

Urinary incontinence is not dangerous per se. It is surprising that despite reduced quality of life, only one third of those affected seek medical help [5]. The condition incurs significant costs for physician consultations, medications, incontinence aids, catheters, physical therapy, surgery, laundry, clothing, skin or urinary tract infection treatments, carpet and furniture cleaning: $17.5 billion annually in the U.S. and nearly €4 billion in Germany [6,7]. Urinary incontinence can be treated, provided that this taboo subject is addressed openly.

Etiology of urinary incontinence

The lower end of the abdominal cavity is formed by the pelvic floor. The upright gait increases abdominal pressure. The pelvic floor must counteract this throughout its life and at the same time enable the physiological functions of micturition, defecation and reproduction. Pregnancy and (especially vaginal) childbirth acutely damage the pelvic floor, while obesity, chronic cough, lung disease or constipation chronically overstress the pelvic floor. Other risk factors include estrogen deficiency, hysterectomy, cognitive impairment, smoking, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and probably inherited connective tissue weakness [8]. Since many of these risk factors increase with age and increasing life expectancy leads to longer-lasting stress on the pelvic floor, urinary incontinence is a health concern, especially for older individuals. Aging processes such as change of the muscle connective tissue portion to the disadvantage of the muscle portion seem to negatively influence the function and structure of the pelvic floor and thus the complex continence mechanism. In women, the urethra lies on the endopelvic fascia and anterior vaginal wall: it is suspended laterally from the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis and is tightened and stabilized by the levator muscle (DeLancey’s hammock theory) [9]. This support layer is suspended like a trampoline anteriorly from the ligamenta pubourethralia (suburethral suspension), laterally from the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, and dorsally from the ligamenta sacrouterina and cardinalia (integral theory of Petros and Ulmsten) [10]. Thus, when intra-abdominal pressure increases, the urethra is pressed against this hammock-like support layer and its lumen is occluded. Damaged or weakened pubourethral ligaments can lead to a hypermobile urethra and ultimately stress incontinence. The principle of incontinence slings is aimed at their correction. Urethral closure pressure due to contraction of the urethral sphincter additionally contributes to the continence mechanism. The number and diameter of its muscle fibers decrease approximately 2% per year of life, which explains the observation in urodynamics of decreasing urethral resting occlusion pressure with age histomorphologically [11,12]. Corresponding age-related changes are also found for the anterior compartment on the pelvic floor [8].

All this explains the development of stress incontinence and genital descensus. Because estrogen receptors have been demonstrated in the squamous epithelium of the proximal and distal urethra, vagina, bladder trigonum, and also in the retaining apparatus of the pelvic floor (e.g., pubococcygeus muscle) in premenopausal women, estrogen deficiency is considered to be partly responsible for the development of pelvic floor insufficiency in the elderly [13–16]. Age-related central nervous and peripheral nerve changes such as reduction of acetylcholinesterase-positive nerves and number of axons in the bladder muscle in turn affect micturition with development of OAB and also lead to a decrease in electromyographic activity [17–21]. This denervation occurs more in women who have given birth, after pelvic surgery, or in neuropathy [22–24].

Diagnostics

Even if the patient does not bring up this taboo subject of her own accord, the incontinence-specific anamnesis should still include information about situations involving urine leakage, the need for pads, symptoms of prolapse (typically a feeling of vaginal pressure, foreign body sensation or lower abdominal discomfort that increases during the day and improves when lying down), hematuria, urogenital infections, births (vacuum or forcep deliveries are more often associated with pelvic dysfunction) and birth injuries, pelvic surgery or radiation, neurological and endocrinological disorders, gastrointestinal complaints, medication use, and sexual and stool history. [25]. A micturition diary for two to three days allows micturition and drinking behavior to be objectified and makes it easier to distinguish between the different forms and causes of incontinence (e.g. polydipsia or isolated nocturia due to cardiac causes) by providing clear information on “frequency”, imperative urination, incontinence episodes, pad consumption, nocturia and polyuria. As can be seen in table 1, the distinction between stress incontinence and OAB can already be made anamnestically. The acronym “DIAPPERS” serves as a mnemonic to rule out possible causes of OAB: delirium, infections (UTI), atrophic urethritis/vaginitis, psychogenic (depression, neurosis), pharmacotherapy, excessive urination, reduced (“restricted”) mobility, and stool masses in the rectum (“stool impaction”) [26]. In cases of continuous urine leakage after pelvic surgery or childbirth, a vesicovaginal fistula should also be considered and ruled out urogynecologically.

Fundamental to the examination is the exclusion of urinary tract infection and residual urine formation. This is well done in the family practice with urine strip rapid test and urine culture resp. Ultrasound examination or disposable catheterization feasible. Any UTI should first be treated for resistance before further workup, as it often presents only with irritative OAB symptoms such as “frequency” or pollakiuria and urinary incontinence in older women without the presence of typical UTI symptoms such as alg or dysuria, and thus can feign (new onset) OAB [27]. Since, on the one hand, both OAB and UTIs are common and increase with age and, on the other hand, UTI symptoms are not always typical in old age, diagnosis becomes more difficult. Conversely, preexisting OAB symptoms may also complicate the recognition of a florid UTI [28].

Residual urine volumes above 100 ml can be the result of genital descensus (bladder emptying disorders, e.g. in cystocele) or neurological causes and thus require further urogynecological clarification. Incidentally, urinary incontinence and residual urine formation are by no means mutually exclusive (overflow incontinence); increased residual urine volumes can promote the development of UTI.

Genital descensus can be rapidly assessed with speculum setting: As a rule of thumb, a descent of the anterior (bladder), posterior (rectum) or apical vaginal wall resp. uterus beyond the hymenal margin distally leading to symptoms. Genital trophism can be assessed with pH test strips (Lakmus paper) or in the native: A pH value ≥4.5 indicates genital atrophy – provided that infection has been excluded. In the native, almost only parabasal cells show up besides possible signs of inflammation. If the bladder is not empty, the cough test can be performed immediately: Urine output synchronized with coughing and visible at the meatus urethrae externus clinically proves stress incontinence. However, a negative cough test does not rule out incontinence.

In case of failure of conservative measures, before surgical therapy, in case of complex history or neurological diseases, but also in case of any unclear or recurrent incontinence, we recommend further urogynecological and urodynamic evaluation for objectification and quantification of urinary incontinence symptoms, which is also useful in older patients [29]. This includes urodynamics by means of cysto- and urethrotonometry as well as mictiometry, supplemented by perineal sonography (visualization of the urethra and bladder neck with an abdominal probe placed on the perineum) and, if necessary, cystoscopy. This urogynecological and urodynamic examination is a mandatory health insurance service.

Thanks to more accurate urodynamic diagnostics, the success of the operation can be better assessed and individualized preoperative patient information can be provided. Thus, ideal patients for an incontinence sling have a normal urethral pressure profile and a mobile urethra. In contrast, unfavorable factors are a deep preoperative maximal urethral closure pressure (<20 cm H2O), pathologic detrusor contractions occurring in filling cystometry (>25 cm H2O), and especially the combination of deep urethral closure pressure and immobile urethra (intrinsic sphincteric insufficiency).

Therapeutic procedure

In postmenopausal patients, we recommend local estrogenization for all forms of incontinence. Oral systemic hormone therapy in the treatment of SUI showed worsening of incontinence symptoms in the HERS trial; however, the data are less clear for local estrogenization [30–32]. Not to be dismissed are the reduction in the incidence of UTI from 5.9 to 0.5 per year and the normalization of vaginal flora by intravaginally administered estriol in postmenopausal women [33].

Since age seems to be by far the more important predictive factor for the development of stress incontinence than menopausal status, the purpose of estrogen replacement may be rather prevention or prevention of stress incontinence. in postponing the symptomatology [34–38].

Physical therapy for pelvic floor rehabilitation helps with SUI and OAB. We were able to show comparable success rates for younger and older patients [39]. In the case of OAB, additional behavioral therapy with bladder training to gradually increase micturition volumes resp. Extending the interval and keeping a micturition calendar for self-monitoring are part of the treatment. In terms of fluid management, attention should be paid to a daily drinking quantity of approx. 1.5 l, divided into four portions.

Anticholinergics are considered first-line pharmacotherapy for OAB. They reduce imperative urination by 50%, incontinence episodes by 70% (0.6 incontinence episodes per day), “frequency” by 20-30% and improve quality of life [40]. The effect occurs after one week and reaches its maximum after eight to twelve weeks. However, compliance is poor: after six to twelve months, only one-fifth are still taking the drug, either because it has an insufficient effect or because of intolerable side effects such as dry mouth in 25%, constipation in 10%, and central disturbances such as nausea, fatigue, poor concentration, and blurred vision in up to 12% of cases. Contraindications to anticholinergics include untreated narrow-angle glaucoma, stenoses in the gastrointestinal tract, or tachycardic arrhythmias. A new class of drugs with a different mechanism of action are the B3 adrenoceptor agonists, which directly relax the bladder depressor. They are comparable in effect to anticholinergics, but without anticholinergic side effects. The most common side effects are hypertension, urinary tract infections, headache, and nasopharyngitis.

Incontinence pessaries and tampons are a viable alternative for motivated patients. The patient inserts these aids vaginally by herself during the day as needed and removes them in the evening. Not to be forgotten for any urinary incontinence are the incontinence pads freely available on the market, which in Switzerland are reimbursed differently by health insurance companies depending on the degree of severity (means and objects list MiGeL 15.01-15.07).

Surgical treatment of stress incontinence

The gold standard of surgical treatment of stress incontinence in women with a (hyper)mobile urethra today is tension-free vaginal slings. Based on the results of our own studies, we prefer the original method: the retropubic “tension-free vaginal tape” (TVT) developed by Ulmsten and Petros and introduced in 1995 [41–43]. This minimally invasive snare technique involves implantation of a nonabsorbable macroporous and monofilament polypropylene tape, which is inserted under local anesthesia and analgesia through a 1 cm long suburethral colpotomy at the level of the middle urethral segment (midurethra) is passed behind the symphysis with special needles and is further passed retropubically to the abdominal wall directly above the symphysis from two suprasymphysary stab incisions. One therefore speaks of “midurethral” or “suburethral” slings. The terms are used synonymously here. The principle of action is to strengthen the weakened pubourethral anchorage and stabilize the midurethra, but without elevating or obstructing it. The procedure is performed in a short-stay inpatient setting. The objective cure rate is 90% [44]. Retropubic banding explains the possible intraoperative complications such as bladder perforation, bowel injury, or hemorrhage, which is why the transobturator approach was developed to reduce them [45,46]. Postoperatively, about 5% bladder voiding dysfunction and about 7% de novo urge symptoms can be expected.

When the urethra is less mobile to fixed and hypotonic, it is referred to as intrinsic sphincteric insufficiency. This form of stress incontinence manifests itself, for example, as recurrent incontinence after incontinence surgery, as a result of which the urethra has become rigid and hypotonic. It is prognostically less treatable. This is where periurethral injection of bulking agents comes in: These locally stretch the periurethral tissue and constrict the urethra, thereby increasing pressure transmission in the proximal or middle urethra [47]. Since this technique is much less invasive than TVT and can be performed under local anesthesia, it is also suitable as a therapy for multimorbid patients. However, success rates of 76% at one year and 48% at two years are significantly lower than for TVT, and bulking agents are not covered by insurance.

Botulinum neurotoxin in the treatment of overactive bladder.

In refractory idiopathic or neurogenic overactive bladder, whether because of intolerable anticholinergic or B3 sympathomimetic drug side effects or because of contraindications to drug therapy, botulinum neurotoxin can be injected into the bladder muscle and under the urothelium under local anesthesia or anesthesia with cystoscopic visualization [48,49]. Usually, 100 units of type A (Botox®) are injected for idiopathic OAB. In Switzerland, this therapy is a compulsory service for refractory OAB, provided that it is administered at a center or in a hospital. evaluated and implemented with appropriate expertise. Botulinum neurotoxin type A prevents the release of acetylcholine at the motor end plate. This chemodenervation is reversible and lasts for about three months at the efferents of striated skeletal muscle and eight to ten months at the smooth muscle (detrusor vesicae muscle), but also affects the afferents. The patient feels the onset of action increasingly from the second day [50]. After two weeks, the residual urine must be checked. This may occasionally amount to several hundred milliliters for a few weeks or months; if bladder emptying disorders or urinary tract infections also occur, (self)catheterization must be performed. Otherwise, residual urine can be closely monitored. This is because the effect of chemodenervation decreases over the weeks and months, under which the amount of residual urine also normalizes. Success rates as measured by reduction in incontinence episodes range from 67 to 100% for idiopathic OAB, depending on the study [51]. The prospective Swiss multicenter study showed a statistically significant improvement in bladder function and quality of life in 88% [49]: After only two weeks, 82% were relieved of urge symptoms and 86% of incontinence, and micturition frequency was practically normalized with corresponding recovery of maximum bladder capacity. Contraindicated use in malignant bladder tumors, pregnancy and lactation, renal insufficiency, and florid urinary tract infection. We are also very cautious about diabetes mellitus. Reinjections in case of diminished effect should be performed at the earliest after three months to avoid antibody formation. Clinical practice shows that we need to repeat Botox injections only after one or two years.

Take-Home Messages

- Diagnosis and treatment of urinary incontinence differ only insignificantly for young and old patients.

- Urinary tract infection and increased residual urine should always be ruled out with any new onset of urinary incontinence.

- While stress incontinence is addressed surgically (or mechanically), overactive bladder is primarily treated with medication.

- At the latest when conservative measures such as anticholinergics or physiotherapy are unsuccessful, a urogynecological and urodynamic evaluation is indicated.

Literature:

- Hannestad YS, et al: A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT study. Epidemiology of incontinence in the county of Nord-Trondelag. J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53(11): 1150-1157.

- Buckley BS, et al: Prevalence of urinary incontinence in men, women, and children–current evidence: findings of the Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence. Urology 2010; 76(2): 265-270.

- Olsen AL, et al: Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1997; 89(4): 501-506.

- Abrams P, et al: The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 2003; 61(1): 37-49.

- Hunskaar S, et al: The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU Int 2004; 93(3): 324-330.

- Hu TW, et al: Costs of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in the United States: a comparative study. Urology 2004; 63(3): 461-465.

- Klotz T, et al: The economic costs of overactive bladder in Germany. Eur Urol 2007; 51(6): 1654-1662; discussion 62-63.

- Scheiner D, Betschart C, Perucchini D: [Aging-related changes of the female pelvic floor]. Ther Umsch 2010; 67(1): 23-26.

- DeLancey JO: Structural support of the urethra as it relates to stress urinary incontinence: the hammock hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 170(6): 1713-1720; discussion 20-23.

- Petros PE, Ulmsten UI: An integral theory of female urinary incontinence. Experimental and clinical considerations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 1990; 153: 7-31.

- Perucchini D, et al: Age effects on urethral striated muscle. I. changes in number and diameter of striated muscle fibers in the ventral urethra. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002; 186(3): 351-355.

- Rud T: Urethral pressure profile in continent women from childhood to old age. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1980; 59(4): 331-335.

- Iosif CS, et al: Estrogen receptors in the human female lower uninary tract. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981; 141(7): 817-820.

- Blakeman P, Hilton P, Bulmer J: Mapping estrogen and progesterone receptors throughout the female urinary tract. Neurourol Urodyn 1996; 15: 324-325.

- Ingelman-Sundberg A, et al: Cytosol estrogen receptors in the urogenital tissues in stress-incontinent women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1981; 60(6): 585-586.

- Smith P: Estrogens and the urogenital tract. Studies on steroid hormone receptors and a clinical study on a new estradiol-releasing vaginal ring. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 1993; 157: 1-26.

- Griffiths DJ, et al: Urge incontinence and impaired detrusor contractility in the elderly. Neurourol Urodyn 2002; 21(2): 126-131.

- Griffiths DJ, et al: Characteristics of urinary incontinence in elderly patients studied by 24-hour monitoring and urodynamic testing. Ageing 1992; 21(3): 195-201.

- Griffiths DJ, et al: Cerebral aetiology of urinary urge incontinence in elderly people. Ageing 1994; 23(3): 246-250.

- Gilpin SA, et al: The effect of age on the autonomic innervation of the urinary bladder. Br J Urol 1986; 58(4): 378-381.

- Aukee P, Penttinen J, Airaksinen O: The effect of aging on the electromyographic activity of pelvic floor muscles. A comparative study among stress incontinent patients and asymptomatic women. Maturitas 2003; 44(4): 253-257.

- Olsen AL, et al: Pelvic floor nerve conduction studies: establishing clinically relevant normative data. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003; 189(4): 1114-1119.

- Allen RE, et al: Pelvic floor damage and childbirth: a neurophysiological study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990; 97(9): 770-779.

- Bidmead J, Cardozo LD: Pelvic floor changes in the older woman. Br J Urol 1998; 82(Suppl 1): 18-25.

- Betschart C, Scheiner DA, Perucchini D: No. 1: Clarification in urinary incontinence and genital descensus. Gynecology 2012.

- Resnick NM: Urinary incontinence. Public Health Rep 1987; 102(4 Suppl): 67-70.

- Arinzon Z, et al: Clinical presentation of urinary tract infection (UTI) differs with aging in women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012; 55(1): 145-147.

- Mirsaidov N, Wagenlehner FM: [Urinary tract infections in the elderly]. Urologist A 2016; 55(4): 494-498.

- Resnick NM, Yalla SV, Laurino E: The pathophysiology of urinary incontinence among institutionalized elderly persons. N Engl J Med 1989; 320(1): 1-7.

- Grady D, et al: Postmenopausal hormones and incontinence: the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study. Obstet Gynecol 2001; 97(1): 116-120.

- Hendrix SL, et al: Effects of estrogen with and without progestin on urinary incontinence. JAMA 2005; 293(8): 935-948.

- Steinauer JE, et al: Postmenopausal hormone therapy: does it cause incontinence? Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106(5 Pt 1): 940-945.

- Raz R, Stamm WE: A controlled trial of intravaginal estriol in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med 1993; 329(11): 753-756.

- van Geelen JM, Hunskaar S: The epidemiology of female urinary incontinence. European Clinics in Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2005; 1(1): 3-11.

- Iosif CS, Bekassy Z: Prevalence of genito-urinary symptoms in the late menopause. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1984; 63(3): 257-260.

- Hilton P: Urethral pressure measurement by microtransducer: observations on the methodology, the pathophysiology of stress incontinence and the effects of treatment in the female (MD Thesis). University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1981.

- Jolleys JV: Reported prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in a general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988; 296(6632): 1300-1302.

- Fantl JA, Cardozo L, McClish DK: Estrogen therapy in the management of urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis. First report of the Hormones and Genitourinary Therapy Committee. Obstet Gynecol 1994; 83(1): 12-18.

- Betschart C, et al: Pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence: a comparison of outcomes in premenopausal versus postmenopausal women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2013; 19(4): 219-224.

- Wein AJ, Rackley RR: Overactive Bladder: A Better Understanding of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. The Journal of Urology 2006; 175(3): S5-S10.

- Ulmsten U, Petros P: Intravaginal slingplasty (IVS): an ambulatory surgical procedure for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1995; 29(1): 75-82.

- Scheiner DA, et al: Twelve months effect on voiding function of retropubic compared with outside-in and inside-out transobturator midurethral slings. Int Urogynecol J 2012; 23(2): 197-206.

- Betschart C, et al: Patient satisfaction after retropubic and transobturator slings: first assessment using the Incontinence Outcome Questionnaire (IOQ). Int Urogynecol J 2011; 22(7): 805-812.

- Nilsson CG, et al: Seventeen years’ follow-up of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure for female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 2013; 24(8): 1265-1269.

- Delorme E: [Transobturator urethral suspension: mini-invasive procedure in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women]. Prog Urol 2001; 11(6): 1306-1313.

- de Leval J: Novel Surgical Technique for the Treatment of Female Stress Urinary Incontinence: Transobturator Vaginal Tape Inside-Out. European Urology 2003; 44(6): 724-730.

- Kuhn A, et al: Where should bulking agents for female urodynamic stress incontinence be injected? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008; 19(6): 817-821.

- Schurch B, Schmid DM, Stohrer M: Treatment of neurogenic incontinence with botulinum toxin A. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(9): 665.

- Schmid DM, et al: Experience with 100 cases treated with botulinum-A toxin injections in the detrusor muscle for idiopathic overactive bladder syndrome refractory to anticholinergics. J Urol 2006; 176(1): 177-185.

- Kalsi V, et al: Early effect on the overactive bladder symptoms following botulinum neurotoxin type A injections for detrusor overactivity. Eur Urol 2008; 54(1): 181-187.

- Schurch B: Botulinum toxin for the management of bladder dysfunction. Drugs 2006; 66(10): 1301-1318.

- Fialkow MF, et al: Lifetime risk of surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008; 19(3): 437-440.

- Smith FJ, et al: Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116(5): 1096-1100.

- Abrams P, Wein AJ: The Overactive Bladder: A Widespread and Treatable Condition. Erik Sparre Medical AB 1998.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(5): 16-22