Psychiatric symptoms are a crucial aspect of Huntington’s disease. An overview of symptom assessment and treatment options.

Psychiatric symptoms are a crucial aspect of Huntington’s disease. They also frequently occur in the prodromal stage and worsen with disease progression [1].

Huntington’s disease, which occurs with a prevalence of 10.6-13.7/100,000 inhabitants in the Western world, is based on an autosomal dominant inherited polyglutamine disorder caused by an elongation of the CAG repeat in the Huntington’s gene on chromosome 4 [2,3]. The more repeats, the greater the severity and the shorter the latency to first manifestation of symptoms. From a length of 39 repeats, the disease becomes clinically manifest [4]. Subsequently, there is degeneration of gaba and cholinergic neurons in the neostriatum and atrophy of the corpus striatum.

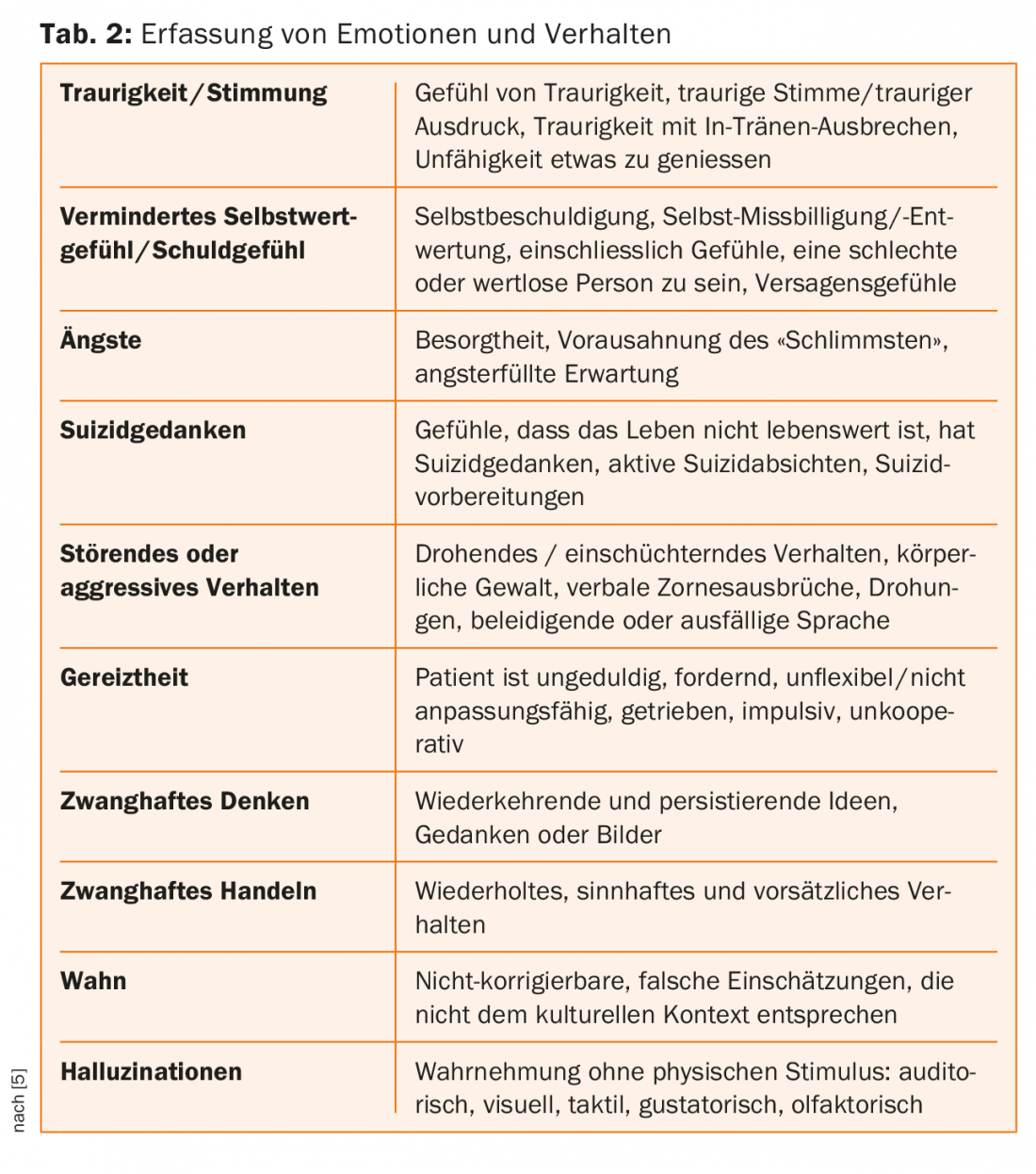

Neuropsychiatric symptoms can be divided into four subdomains: Drive, Affect, Delusion, and Personality Changes [5]. Obsessive-compulsive behavior, depression, psychotic symptoms, confabulations, and dementia development may occur. Impairments in cognitive flexibility as well as impulse control are common [6].

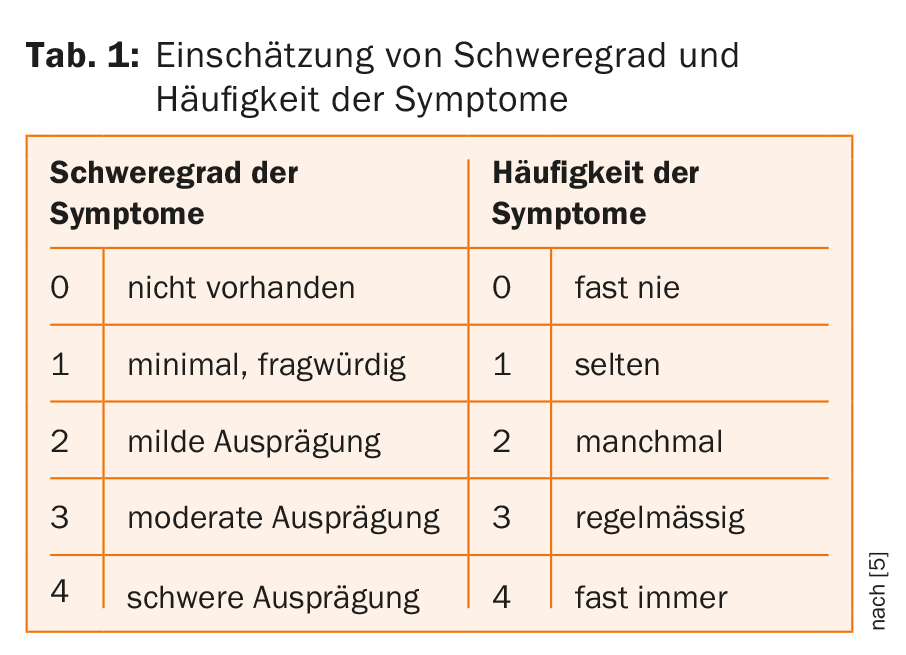

Together with the recording of the patient’s behavior, quality of life, and functioning, psychiatric symptoms are evaluated in the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) examination standard, with ratings on a Likert scale of 0-4 regarding their severity [5] – cf. Table 1. In addition to depression, increased irritability is also observed in the course of the disease; this is often already found in the prodromal or early-manifest stage. The usually absent insight into illness is attributed to the deteriorated function in the frontal lobe and the reduced conduction toward the corpus striatum [7].

However, these psychiatric symptoms may also be present in other neurological or psychiatric disorders, making early diagnosis of Huntington’s disease based on psychiatric symptoms difficult [1].

Typical motor symptoms include choreatic movements: involuntary, arrhythmic, brief muscle contractions that occur in alternating regions of the body. In addition, vegetative symptoms include sleep disturbances, weight loss, and libido changes [6]. In the classic variant of the disease, there are early – in addition to choreatic movements – disorders of eye movements, dystonia, and motor impersistence in performing simple motor actions. The motor impairments decrease the life expectancy of patients, due in part to falls and aspiration pneumonia [2].

Medical history and status

The 42-year-old IV recipient was assigned to inpatient therapy by her treating psychologist. In the family environment there had been increasing conflicts due to an externally perceived change in the patient’s character. This had already begun five years ago, and the patient was now visibly irritable, verbally aggressive and less and less able to cope with stress. She is prone to impulsive, emotional outbursts and makes incomprehensible insinuations to family members. The patient had become “more suspicious” and had withdrawn socially. In the morning, she had increasing difficulty getting up and was listless. She had stopped fulfilling her household and parenting duties and at times exhibited “bizarre behavior.” The husband had moved out due to the deteriorating situation, and the two joint children lived with the sister-in-law. The patient herself expressed that she felt that her sister-in-law wanted to take her children away from her.

As a result of a serious bicycle accident 18 years ago, she is IV-disabled. Otherwise, there were no known pre-existing physical or psychiatric conditions, and the history of addiction was bland.

The patient had no insight into the disease and little motivation for treatment. On admission, there was a discrete, involuntary mobility disturbance, which the patient stated that she did not notice herself. When asked, the husband reported increasing movement disorders of the arms and hands as well as the trunk. There were no known psychiatric or neurological disorders in the family, he said.

Clinical findings

Psychopathological findings showed decreased attention, memory, and concentration. The formal train of thought was ordered, the thinking narrowed. The patient appeared suspicious, irritable and brooding, unstable in affect, easily deflectable to the depressive pole. There was a paranoid delusion regarding the sister-in-law, no evidence of sensory delusions or ego disorders. Except for motor restlessness, the patient was psychovegetatively inconspicuous. There were no indications of acute danger to the patient or others. Neurologically, in addition to the discrete choreatic movements, the residual condition after traffic accident and plastic reconstruction (latissimus dorsi plasty) of the lower leg with paresis and sensory disturbances due to post-traumatic peroneal paralysis was impressive. There were slight disturbances in fine motor skills and coordination as well as an unsteady, asymmetrical gait pattern with stiffening limp. Pressure, temperature, and pain sensations on the left lower leg were reported to be increased.

Diagnosis and clinical course

A good month after admission in domo, a presentation was made at the neurological clinic of the Lucerne Cantonal Hospital on the basis of a suspected diagnosis of Huntington’s disease. There physical examination revealed gaze apraxia, intermittent staccato speech, and dyskinesias of the mouth, jaw, and eyes, as well as oral angle myoclonia and myocloniform finger dyskinesias bilaterally. In addition, there was motor impersistence of the tongue as well as the hands (“milkmaids grip”), dysdiadochokinesia and intermittent choreatic movements as well as increased muscle reflexes of all extremities and a cloniform Achilles tendon reflex bilaterally. Stance and gait ataxia with increase in dyskinesias was imprinted.

The performed examinations EEG, hyperventilation and photostimulation as well as duplex sonography of the cerebral vessels did not show any pathological results. A performed cMRI demonstrated bilateral caudate atrophy without signal abnormalities and mild putaminal atrophy.

This strengthened the suspicion of Huntington’s disease, and tardive dyskinesia due to old narcotics and Wilson’s disease were considered as differential diagnoses.

Therapeutically, quetiapine 300 mg was started in the psychiatric clinic against the affective and delusional symptoms, and the patient was also involved in action-oriented therapies.

A good two months after admission, the patient withdrew at her own request and after consultation with neurology, continuing medication with quetiapine retard 300 mg. On the day of discharge, a molecular genetic examination was performed at the Cantonal Hospital of Lucerne, which provided evidence of a pathological CAG expansion with 46 CAG repeats and thus a confirmed diagnosis of Huntington’s disease.

Despite treatment-relevant mental symptoms, antidyskinetic treatment was not yet necessary because of mild motor symptoms at discharge. In addition to genetic as well as psychological counseling, post-inpatient care by a social service and outreach care was recommended.

Discussion

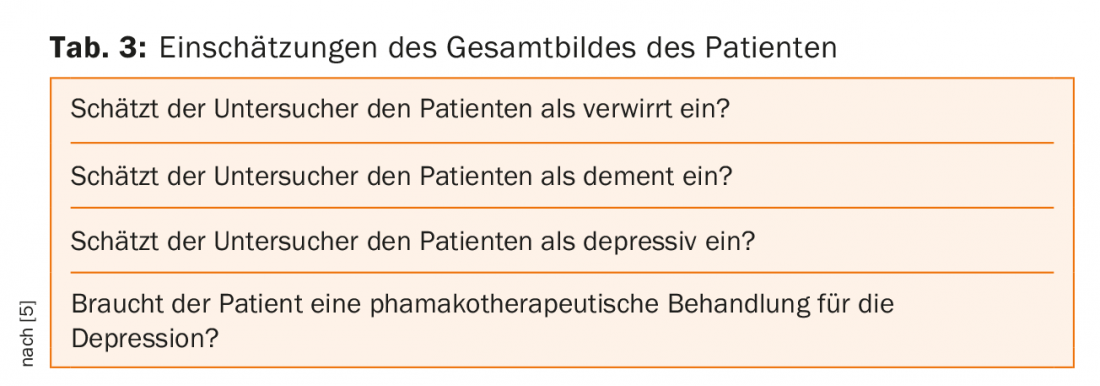

Huntington’s disease is a neuropsychiatric disorder easily diagnosed in the late stages by the choreatic movements (cf. Tab. 1-3 for recording behavioral problems). However, nonspecific neuropsychiatric abnormalities often appear years before the initial manifestation of motor symptoms and severely affect patients’ lives. It is therefore all the more important to include such an “orphan disease” in the differential diagnosis of psychiatrically abnormal patients in order to be able to accompany and care for the patients adequately [8]. In our case, paranoid-mistrustful irritability, lack of impulse control, as well as depressed mood, were leading factors, in addition to the choreatic movements that were in the initial stage.

To date, there are no options for causal therapy, but a wide variety of research is being conducted to determine the best way to influence disease progression [9]. Initial laboratory studies suggest therapeutic possibilities in the near future [10]. Gene ferries, biomarkers or stem cell transplants are discussed as possible curative therapies, but these are not yet applicable, which is why the diagnosis is still considered non-curable [9].

After delivery of the diagnosis, the patient needs comprehensive care and counseling. In addition to functional therapies (occupational and physiotherapy, speech therapy), the start of drug therapy is indicated in the presence of mental symptoms requiring treatment – as in the case described, for example, with affective stabilizing and antipsychotic drugs such as atypical neuroleptics. If needed, tetrabenazine or tiapride can be used to treat disruptive hyperkinesias, and L-dopa can be used to treat parkinsonoid symptoms. Genetic counseling and social and psychotherapeutic support for affected patients and families are of great importance.

Take-Home Messages

- Huntington’s disease can cause debilitating neuropsychiatric symptoms during the prodromal phase or in the early stages.

- The neuropsychiatric symptoms come from four subdomains: drive, affect, delusion, and personality changes.

- The patient often has no insight into the disease, even if the relatives and the environment suffer.

- An assessment of symptoms can be made, for example, by recording behavioral abnormalities in the “Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale” (UHDRS).

- Atypical antipsychotics and psychotherapeutic support can be used in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Literature:

- Epping EA, Kim JI, et al: Longitudinal Psychiatric Symptoms in Prodromal Huntington’s Disease: A Decade of Data. Am J Psychiatry. 2016; 173(2): 184-192.

- Pringsheim T, Wiltshire K, et al: The incidence and prevalence of Huntington’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2012; 27(9): 1083-1091.

- McColgan P, Tabrizi SJ: Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. Eur J Neurol. 2018; 25(1): 24-34.

- Paulson HL, Albin RL: Huntington’s Disease: Clinical Features and Routes to Therapy. In: Neurobiology of Huntington’s Disease: Applications to Drug Discovery (eds Lo DC, Hughes RE): 2011.

- Kieburtz K: Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale: Reliability and-Consistency. Movement Disorders. 1996 II(2): 136-142.

- Duff K, Paulsen JS, et al: Predict HDIotHSG. Psychiatric symptoms in Huntington’s disease before diagnosis: the predict-HD study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007; 62(12): 1341-1346.

- Hoth KF, Paulsen JS, et al: Patients with Huntington’s disease have impaired awareness of cognitive, emotional, and functional abilities. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007; 29(4): 365-376.

- Schiefer J, Werner C, et al: Clinical diagnosis and management in early Huntingtons disease: a review. Degenerative Neurological and Neuromuscular Disease. 2015; (5): 37-50.

- Lo DC, Hughes RE, editors. Neurobiology of Huntington’s Disease: Applications to Drug Discovery. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2011.

- Chen GL, Ma Q, et al: Modulation of nuclear REST by alternative splicing: a potential therapeutic target for Huntington’s disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2017; 21(11): 2974-2984.

Acknowledgments: For clinical support and collaboration, we sincerely thank Prof. Bohlhalter, MD, and Stephan Mittas, MD, of Neurology Lucerne, Dipl. med. Berennen-Dietrich from the Rötgeninstitut Luzern and Roland Spiegel, MD, from Genetica Zurich.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(1): 24-27.