Hepatitis C is the “favorite child” of current medical ethics discussions. However, the new, expensive HCV drugs should not cloud the view of the overall diagnostic and therapeutic situation of the condition. Screening of at-risk populations and correct interpretation of test results remain important. This also applies to hepatitis B.

“Much has happened since hepatitis C virus (HCV) was first described in the late 1980s – when it was still referred to as the causative agent of “non-A/non-B hepatitis.” We witnessed an incredible success story of initial cure rates or ‘sustained virological responses’ [SVR] around 50% under standard therapy with subcutaneous (pegylated) interferon alpha and oral ribavirin [1] to almost complete cure under the new interferon-free combinations, the so-called direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAA), which entered the market in 2014,” said Prof. Andrea De Gottardi, MD, Senior Physician Hepatology, Inselspital Bern. “These new combinations allow for a simpler and shorter, besides an oral therapy regimen with good tolerability. They target key components of viral replication.”

In Switzerland, HCV primarily affects those born between 1950 and 1985 – this is shown by epidemiological data. Up to 85% of all acute hepatitis C cases progress naturally to a chronic form, which in turn leads to liver cirrhosis in about one fifth in the long term, i.e. after one or more decades. In Switzerland, it is estimated that 36,000 to 43,000 people have chronic HCV infection. The final stage is the threat of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

“Accordingly, treatment of chronic hepatitis C should prevent cirrhosis and address the extrahepatic manifestations. These include, for example, MP glomerulonephritis, cryoglobulinemia, Raynaud’s syndrome, and systemic vasculitis. Approximately 15% of patients are affected. There is further evidence of hepatitis C-induced insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes. Neurologically, fatigue and depression may occur,” explained Prof. De Gottardi. “If nothing else, HCV therapy curbs further transmission.”

Indication and mechanism of action

The new antiviral therapies are used (according to the FOPH limitatio) in the following cases

- Biopsy-proven liver fibrosis grade 2, 3, or 4 (Metavir score) or increased liver stiffness of ≥7.5 kPa measured by fibroscan (this involves sending a pulse wave through the liver and measuring the velocity of propagation)

- symptomatic patients with an extrahepatic manifestation (although health insurers do not accept every extrahepatic manifestation as an indication)

- Patients with HIV and/or HBV co-infection

- i.v. drug users (“people who inject drugs”, PWID) in a controlled program (substitution treatment)

- a disease relapse after treatment failure.

The goal of combination therapy is to target HCV at various stages of its viral life cycle. Agents with the “-asvir” suffix inhibit non-structural protein 5A (NS5A). Substances with the suffix “-previr” are inhibitors of the protease NS3/4A. The “-buvir” endings indicate polymerase inhibitors (NS5B).

Combinations available at the time of the congress, depending on the genotype, are called:

- Harvoni® (sofosbuvir, ledipasvir ± ribavirin)

- Viekirax®/Exviera® (ombitasvir, paritaprevir, ritonavir, dasabuvir ± ribavirin)

- Daklinza®/Sovaldi® (daclatasvir, sofosbuvir)

- Zepatier® (grazoprevir, elbasvir)

- Epclusa® (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir).

How and whom to test?

Serology for anti-HCV antibodies should be performed first. If this is negative, there is no HCV exposure in the past – if it is positive, however, further diagnostic steps must be taken (HCV-RNA). A negative HCV RNA result means “status post or freedom from chronic hepatitis C” (no active viral replication), a positive result requires HCV genotyping and referral to the specialist.

“Hepatitis C meets all the criteria for screening,” the speaker noted. This includes the fact that it is an important health problem that can be present in a latent stage and can be effectively treated with appropriate medications. The facilities or possibilities for diagnosis and therapy exist in Switzerland. There is also an appropriate test procedure that is acceptable to the affected population and economically justified.

Risk populations that would be appropriate for screening can be elicited through medical, behavioral, occupational, or demographic factors (risk-based screening approach). These include, but are not limited to, individuals with elevated transaminases, with previous invasive treatments or even tattoos/piercings from infectiologically insufficiently controlled facilities, e.g. abroad, (former) drug users (intranasal/intravenous), migrants from endemic areas, (former) prisoners, pregnant women and children of an infected mother, blood product recipients before 1992 (in Switzerland), and those born between 1950 and 1985.

Other requirements for hepatitis B

Basically, hepatitis B is a dynamic chronic infection for which, unlike HCV, there is no cure (can be suppressed but not eliminated). The viral DNA remains in circular form in the nucleus of infected hepatocytes. The risk for cirrhosis and HCC is associated with high viremia and inflammation. Reactivation is possible under immunosuppression.

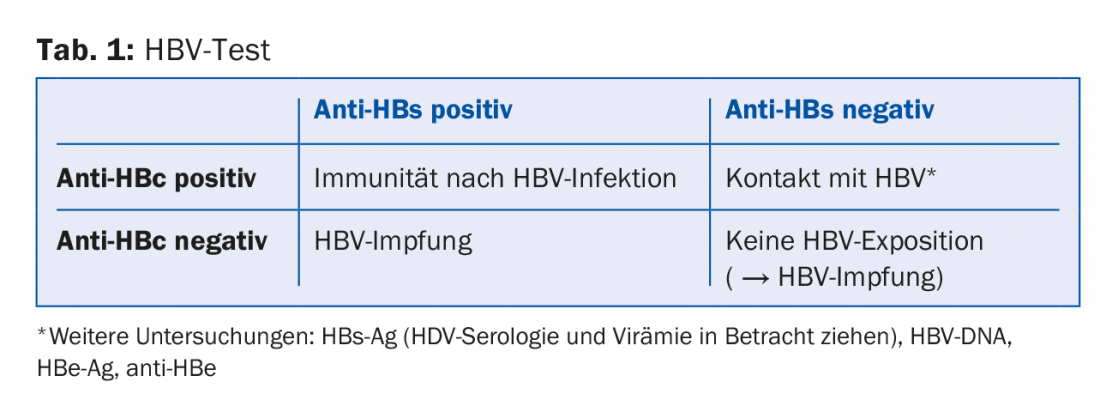

The individual tests answer different questions:

- Has my patient had contact with HBV? → Anti-HBc antibody

- If so, is he immune? → Anti-HBs antibody

A corresponding test scheme is shown in table 1.

The goal of treatment is immune control of HBV. Treatment requirements are HBV DNA >2000 IU/ml, elevated transaminases, and hepatic fibrosis (i.e., not all patients need treatment). There are subcutaneous and oral therapeutic strategies. Subcutaneous (PEG) IFN therapy for 48 weeks has the advantage that a sustained virologic response can be expected after the end of therapy and there is the (albeit small) possibility of HBs-Ag loss. However, tolerance is low and there are many contraindications (decompensation, comorbidities, etc.).

Source: 2nd Spring Congress of the SGAIM, May 3-5, 2017, Lausanne

Literature:

- Webster DP, Klenerman P, Dusheiko GM: Hepatitis C. Lancet 2015; 385(9973): 1124-1135.

Further reading:

- European Association for the Study of the Liver: EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2016.

- Journal of Hepatology 2017; 66(1): 153-194. www.easl.eu/research/our-contributions/clinical-practice-guidelines/detail/easl-recommendations-on-treatment-of-hepatitis-c-2016

- European Association for the Study of the Liver: EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology 2017 (in press). www.easl.eu/research/our-contributions/clinical-practice-guidelines/detail/easl-2017-clinical-practice-guidelines-on-the-management-of-hepatitis-b-virus-infection

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(7): 33-34