The incidence of endometrial cancer is increasing. In postmenopausal women, it usually becomes noticeable early on with vaginal bleeding. More than 70% of patients are in FIGO stage I at diagnosis. Surgical therapy consists of hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, and depending on the risk profile, sentinel, and/or pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy. Adjuvant therapy is based on stage classification and risk of recurrence.

Endometrial cancer is the most common malignant gynecologic tumor and the sixth most common malignancy worldwide. The annual incidence in Western Europe is increasing and is currently 10-25:100,000 women [1]. The disease is usually diagnosed in early stages confined to the uterus and in postmenopausal women due to vaginal bleeding. In premenopause, the disease may manifest itself through changes in the intensity and frequency of menstruation.

New molecular biological classification?

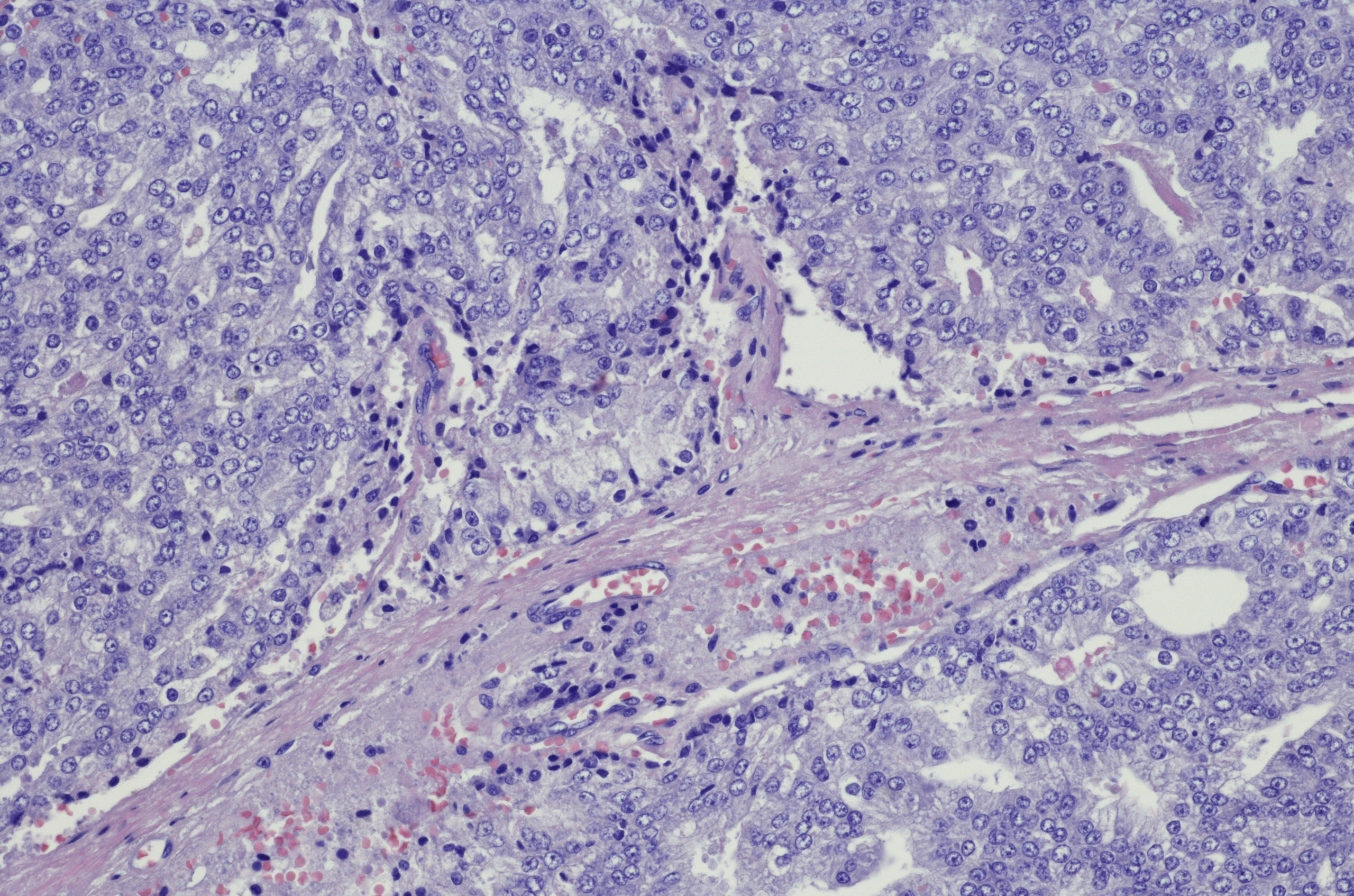

Endometrial carcinoma is classically divided into two categories: Type I, which is more common at 80% and originates from atypical endometrial hyperplasia, corresponds histologically to endometrial adenocarcinomas. Type II carcinomas run a more aggressive course and include clear cell and serous carcinomas as well as carcinosarcomas. However, this classification, based solely on histology, is now being questioned. Currently, a new molecular classification is under discussion, which might be more prognostically and therapeutically relevant. The average age at diagnosis has been considered higher for type II cancers until now. However, a prospective study of more than one million Norwegian women that included 992 type II cancers showed no difference (cut-off age in both groups: 65 years) [2].

Type I endometrial carcinoma is estrogen-dependent. In addition, long-term use of estrogens without progestin protection, metabolic syndrome with obesity, early menarche, late menopause, treatments with tamoxifen, and high estrogen levels (e.g., in polycystic ovary syndrome) are considered risk factors for type I carcinomas. Arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus are also included. In addition, endometrial cancer occurs in 40-60 of patients with Lynch syndrome and in 5-10% of patients with Cowden syndrome.

Hormonal contraception, on the other hand, reduces the risk of endometrial cancer by about 50%. Smoking also appears to be a protective factor. Its protective effect can be explained by the stimulation of hepatic estrogen metabolism. Other protective factors include advanced age at last birth and coffee and tea consumption.

Staging and risk assessment

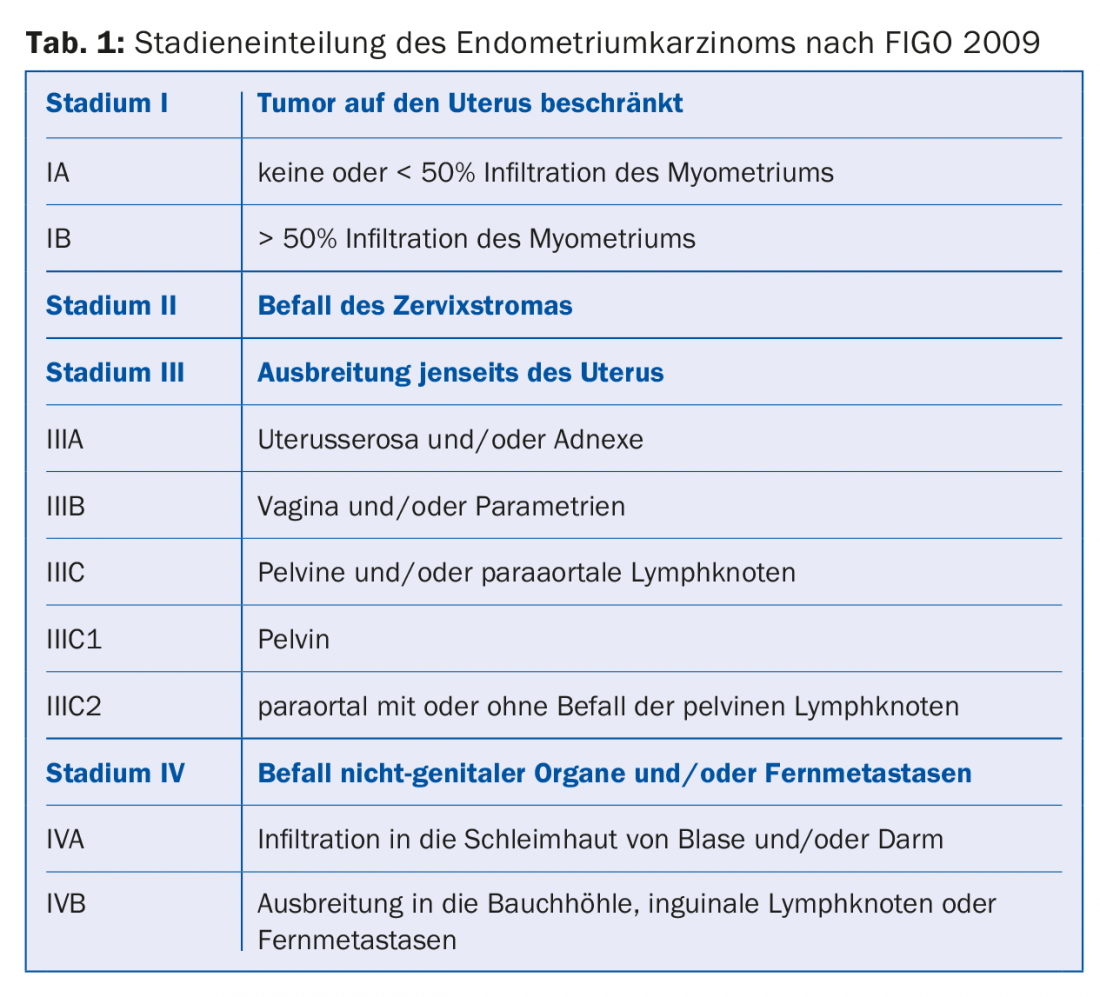

Since 2009, the updated version of staging according to FIGO [3] has been in effect (Table 1) . The 5-year survival for stage IA is ~90%, for stage IB 78% and decreases to 57% for stage IIIC1 resp. to 49% in paraaortic lymph node involvement (IIIC2) [4].

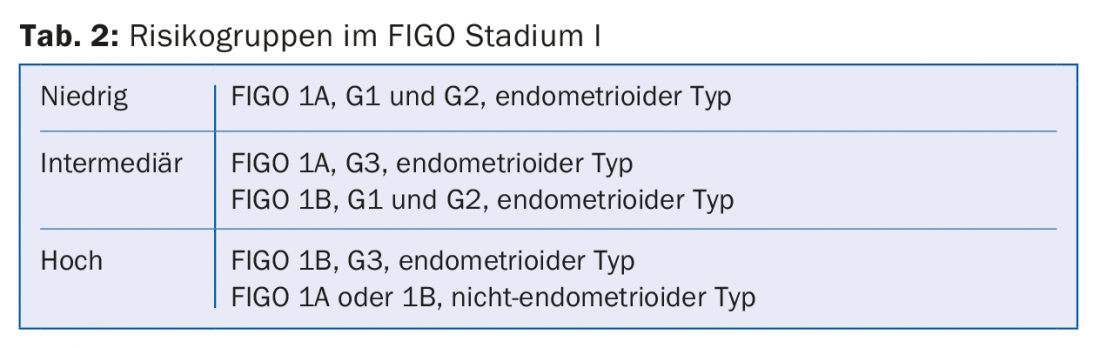

In stage I, three risk groups are defined depending on the histological stage of maturity (G1-3) and histology (endometrioid type vs. non-endometrioid type) (Table 2) . A comprehensive molecular analysis of 373 endometrial carcinomas published in 2013 identified four prognostically distinct subtypes. This could lead to a new classification in the future, which would possibly change the therapy of endometrial carcinoma [5].

Diagnostics

There is no evidence-based screening measure with regard to endometrial cancer. The disease is most often diagnosed in postmenopausal women due to vaginal bleeding. In premenopause, it may be manifested by changes in the intensity and frequency of menstruation. The diagnosis can often already be suspected by means of vaginal ultrasound and then established with the so-called pipelle de cornier (endometrial biopsy). It is important to determine if the source of bleeding is truly the uterine cavity and not the cervix, vagina, rectum, or even bladder. If the pipelle is not possible or the biopsy is not representative, the diagnosis is made by hysteroscopy and curettage. If an advanced stage is suspected, abdominal CT may be performed for preoperative staging.

Surgery

Desire to have children: In cases of urgent desire to have children and well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma in stage T1a, fertility-preserving therapy can be considered if hysteroscopic confirmation has been made that there is no residual carcinoma in utero. Myometrial infiltration as well as ovarian metastasis must be excluded by transvaginal ultrasound, MRI, and laparoscopy. Patients must be informed of the higher likelihood of recurrence, the possibility of progression, and the need for close follow-up. Continuous oral progestin application with medroxyprogesterone acetate 200 mg/d is the treatment of choice. Three-monthly control with transvaginal ultrasound, hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy. Pregnancy should only be attempted after inconspicuous re-staging, if necessary with assisted reproduction, in order to minimize the time to pregnancy. After fulfillment of the desire to have children, surgical therapy appropriate to the stage is necessary because of the high risk of recurrence.

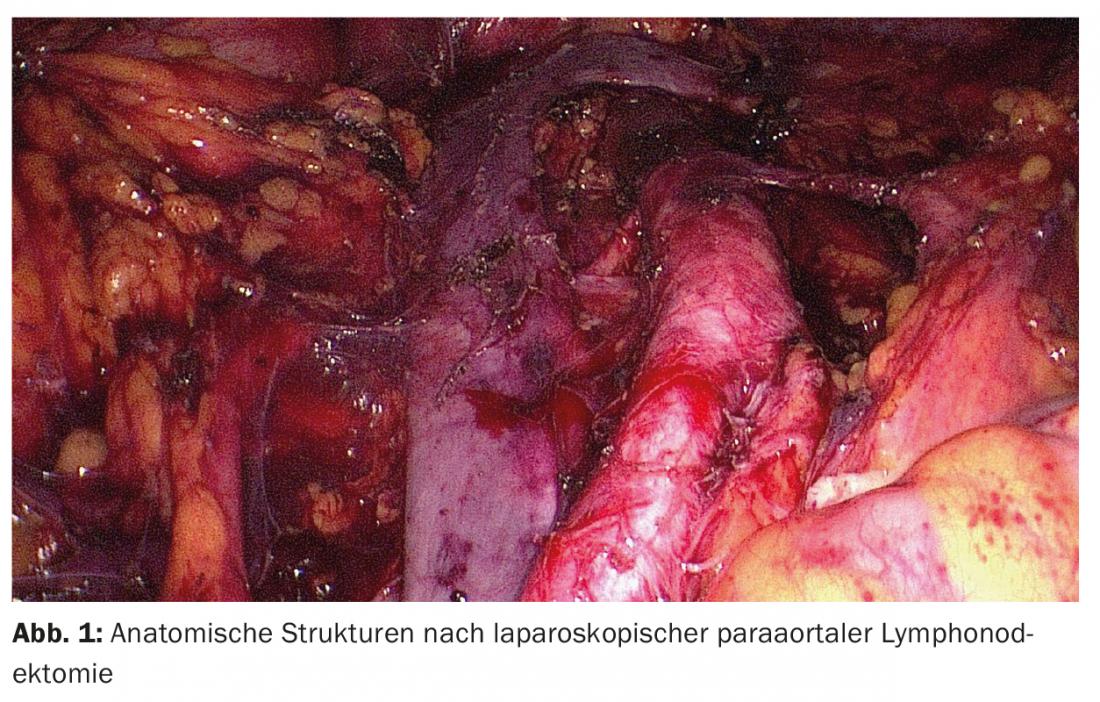

Laparoscopic staging: Except in cases of urgent desire to have a child and high-risk situation with limited operability, surgical therapy is primarily performed. Systematic surgical staging consists of hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, and depending on the risk profile, sentinel and/or pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy. In rare cases, omentectomy is also indicated. Traditionally, staging for endometrial carcinoma has been performed by laparotomy. However, in recent years, various studies have compared staging via laparotomy with staging via laparoscopy [6]. Since the clear advantages of the laparoscopic approach compared to classic open surgery (fewer complications and shorter hospitalization) with the same recurrence frequency and 5-year survival rate have been demonstrated in randomized trials and meta-analyses, surgery should nowadays be performed laparoscopically as a standard procedure (Fig. 1). Regarding robot-assisted surgery, no studies have been published to date that would show an advantage over laparoscopy in the surgical treatment of endometrial carcinoma.

Lymphonodectomy: A key controversial issue is when to perform a lymphonodectomy and to what extent. Two randomized multicenter trials, which unfortunately have serious formal flaws, failed to demonstrate a survival benefit for pelvic lymphonodectomy alone [7,8]. Data on the significance of systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy are sparse; there are no prospective randomized trials. A retrospective cohort study showed that patients at intermediate or high risk of recurrence who underwent pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy had longer life expectancy than those who underwent pelvic lymphonodectomy alone. This benefit was not found at low risk [9].

Although the direct therapeutic effect of lymphonodectomy remains controversial, it is generally accepted that it serves to assess prognosis and decide adjuvant therapy. If the lymph nodes are unremarkable, adjuvant therapy can be omitted, avoiding unnecessary toxicity. Because lymphonodectomy increases both operative and postoperative morbidity, it should be performed only when there is a high probability of carcinoma-affected lymph nodes. A prospective cohort study showed that in patients at intermediate and high risk of recurrence, pelvic lymph nodes were positive in 17% and para-aortic lymph nodes in 12%. 55% of patients with positive pelvic lymph nodes also had positive para-aortic lymph nodes. In addition, 3% of patients with negative pelvic lymph nodes had positive para-aortic lymph nodes.

Interestingly, the majority of patients with positive paraaortic lymph nodes showed involvement between renal vessels and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) [10]. Thus, for intermediate and higher risk of recurrence, pelvic and para-aortic lymphonodectomy is generally recommended. In low-risk settings, on the other hand, the probability of carcinoma-affected lymph nodes remains so low (3-5%) that lymphonodectomy is not performed.

However, lymphonodectomy is associated with intraoperative and postoperative morbidity, as mentioned earlier. The risk of lymphedema is reported to be between 5 and 38%, depending on the study. To circumvent this, the concept of sentinel lymph nodes is currently also being evaluated in endometrial cancer in several ongoing trials. A meta-analysis of 26 studies involving 1101 sentinel lymph node surgeries showed a sensitivity of 93 percent for the detection of lymph node metastases [11]. The ICG technique appears to give the best detection rates (Fig. 2) and may become established in the future [12]. This could capture the infrequently carcinoma-affected lymph nodes at low and intermediate risk of recurrence.

Higher stages: In case of cervical stromal involvement (FIGO II), it may be assumed that the risk for parametrial involvement is similar to that of cervical carcinoma, but this is not confirmed by the current data. It appears that lymphovascular invasion is a better indicator of parametrial spread than cervical stromal involvement. Therefore, radical hysterectomy is not necessarily recommended for FIGO II endometrial cancer. In cases of tumor spread to the vagina and/or parametria (FIGO IIIB), extended radical hysterectomy is performed, with resection of the parametria and, if necessary, colpectomy. In incurable, advanced stages, surgical intervention (hysterectomy for bleeding prophylaxis, debulking of large tumor masses) may be considered in a palliative setting.

Adjuvant treatments

Radiotherapy: the latest Cochrane meta-analysis showed that postoperative percutaneous radiotherapy for low-risk FIGO stage I endometrial cancer does not add benefit [13]. Although external, i.e., percutaneous, radiation improves local tumor control in intermediate and high risk, it may not prolong survival. Because of its lower toxicity with equal efficacy, postoperative vaginal brachytherapy is preferable to external beam radiation for the treatment of early intermediate- to high-risk endometrial cancer.

Adjuvant chemotherapy, combination with percutaneous radiotherapy: only in advanced tumor stages (FIGO III and surgically well-treated patients with FIGO IV disease) is adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin indicated and improves survival by 25% [14]. The PORTEC-3 trial, which will not be completed for several years, is randomly testing percutaneous radiation versus radiochemotherapy in patients with high-risk constellations from stage IB onward.

Recurrences and palliative therapies

Relapses usually occur within three years. The spectrum is broad and includes isolated vaginal recurrences, again curable by local therapies, to disseminated manifestations. Well-differentiated tumors, late relapses, and pulmonary metastases can be better treated, whereas relapses after adjuvant chemotherapy are prognostically unfavorable. There are few data for this situation compared with other tumors, such as temsirolimus or bevacizumab. Palliative hormone therapies are a frequently used and well-tolerated alternative in oligosymptomatic patients with well-differentiated, hormone receptor-positive tumors. Response rates reach ~30% and are not infrequently long-lasting. Medroxyprogesterone acetate (=Farlutal), tamoxifen, which is slightly less effective but clearly better than the aromatase inhibitors letrozole or anastrozole, are used.

Summary and outlook

Endometrial carcinoma is often diagnosed at an early stage. The diagnosis can often be made without complications. More difficult is the adjustment of the radicality of the therapy with the risk profile of the tumor and also the resources of the patient.

In the future, together with molecular differentiation, minimally invasive surgery, and sentinel lymphonodectomy, surgery and adjuvant therapies will be most ideally matched.

Literature:

- Weiderpass E, et al: Trends in corpus uteri cancer mortality in member states of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2014;50: 1675-1684.

- Bjørge T, et. al: Body size in relation to cancer of the uterine corpus in 1 million Norwegian women. Int J Cancer 2007; 120: 378.

- Pecorelli S: Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105: 103-104.

- Lewin SN, et al: Comparative performance of the 2009 international Federation of gynecology and obstetrics’ staging system for uterine corpus cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116: 1141-1149.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Kandoth C, et al: Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013;497: 67-73.

- Santi A, et al: Laparoscopy or laparotomy? A comparison of 240 patients with early-stage endometrial cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(4): 939-43

- Benedetti Panici P, et al: Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100: 1707-1716.

- ASTEC study group, Kitchener H, et al: Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet 2009;373: 125-136.

- Todo Y, et al: Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375: 1165-1172.

- Kumar S, et al: Prospective assessment of the prevalence of pelvic, paraaortic and high paraaortic lymph node metastasis in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014; 132(1): 38-43.

- Kang S, et.al: Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer: meta-analysis of 26 studies. Gynecol Oncol 2011; 123: 522.

- Papadia A, et. al: Laparoscopic Indocyanine Green Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Endometrial Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016; 2206-2211.

- Kong A, et al: Adjuvant radiotherapy for stage I endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4.

- Galaal K, et al: Adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(2): 19-24