Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women. Acute coronary syndrome manifests differently in women than in men. Early recognition of symptoms is essential. Cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology in women change over the life stages. Some cardiovascular entities occur exclusively, or more frequently, in women.

In the last two decades, cardiovascular mortality has been reduced by about 30% overall, thanks to advances in the acute treatment of myocardial infarction, better drugs, devices, and expanded primary prevention. Unfortunately, this success could not be observed to the same extent in the age group of 35- to 50-year-old women. Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death among women worldwide, including in Switzerland. This is not least because the risk of cardiovascular disease in women is often underestimated. There is a widespread belief that women are less likely to have cardiovascular disease or are less likely to die from a cardiovascular event. Reality shows a different picture: according to the FOPH’s cause of death statistics, 35% of all women in Switzerland died of cardiovascular disease in 2014, compared to 31% for men.

This review article addresses the spectrum of cardiac disease in women with a focus on coronary artery disease, sex-specific differences in cardiovascular risk factors, specific diseases unique to women such as coronary artery dissection, pregnancy cardiomyopathy, or Tako-Tsubo syndrome, and features in the cause and treatment of arterial hypertension in women. In addition, the article is devoted to the management of heart disease in women of childbearing age.

Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease and myocardial ischemia – what is different in women?

In women, coronary artery disease manifests not only as atherosclerosis with obstruction of the epicardial coronary vessels. Pathogenetically, microvascular changes, endothelial dysfunction, coronary dissection, and stress-induced cardiomyopathy (Tako-Tsubo) play important roles [1–5].

In approximately two-thirds of all coronary angiographic workups, no coronary artery obstruction can be found despite the presence of ischemia symptoms and objective markers (laboratory chemistry, perfusion defects on cardiac MRI, or ischemia on stress echocardiography). Often microvascular changes are responsible; and frequently the smaller coronary vessels, i.e. arterioles, are affected. The latter are only conditionally amenable to coronary intervention.

In contrast to men, coronary vessels in women are more delicate and small caliber. In addition, hormones play a role: estrogens have a protective effect on endothelial cells, so that relevant stenosing coronary artery disease of the large epicardial vessels occurs less frequently in the pre-menopausal period than in men of the same age [6–8].

The predominant pathomechanisms of thrombotic occlusion of a coronary artery as a cause of acute myocardial infarction are acute plaque rupture on the one hand and plaque erosion on the other. Endothelial damage leads to activation of coagulation and formation of an occlusive thrombus. Autopsy data from the past few decades indicate that plaque erosion is the leading cause of acute myocardial infarction, particularly in younger women, rather than plaque rupture as in men [9]. Microembolization of thrombotic material is consequently more common in women, which can lead to focal necrosis in the myocardium [10,11].

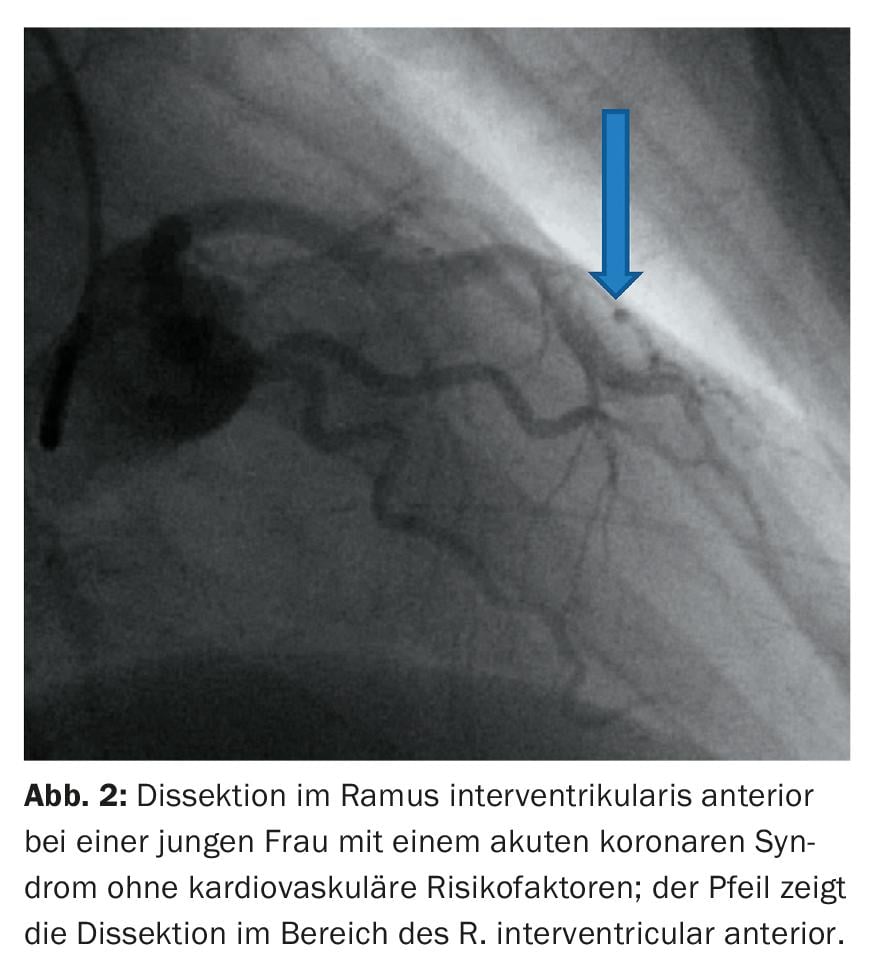

Spontaneous coronary dissection is a rare but important differential diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, especially in young women without a cardiovascular risk profile [11]. There is an increased risk in the peri- and postpartum period, especially in connection with connective tissue diseases and vasculitides.

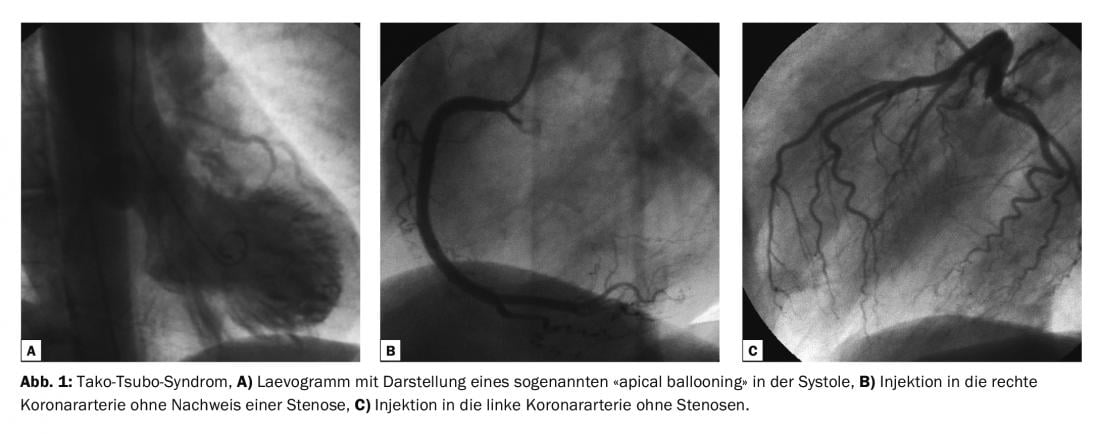

Stress-induced cardiomyopathy (“Tako-Tsubo syndrome”) was first described in Japan in the 1990s. Transient systolic and diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle (typically with akinesia of the apex with hypercontractile basal cuff) in the setting of angiographically often normal or little-altered coronaries is characteristic. Mainly postmenopausal women are affected in this clinical picture, which has a good prognosis. Possible triggers are typically emotional or physical stressful events.

Clinical presentation

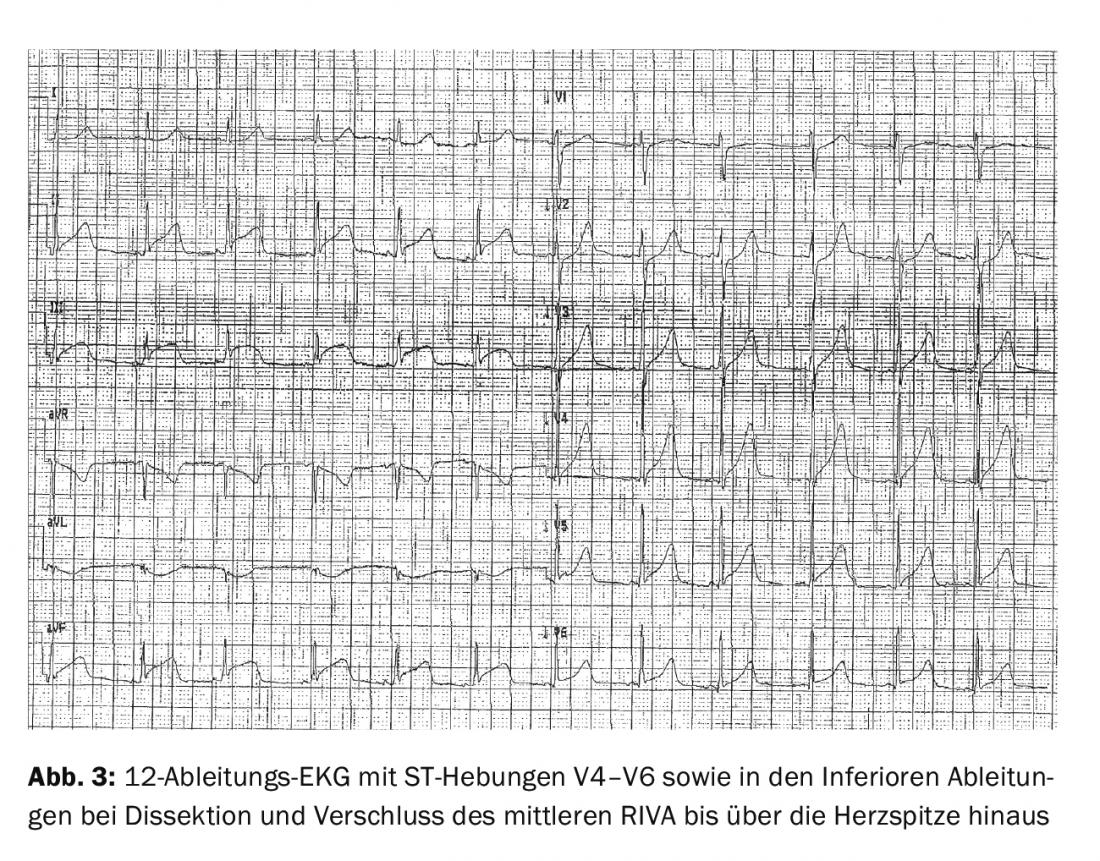

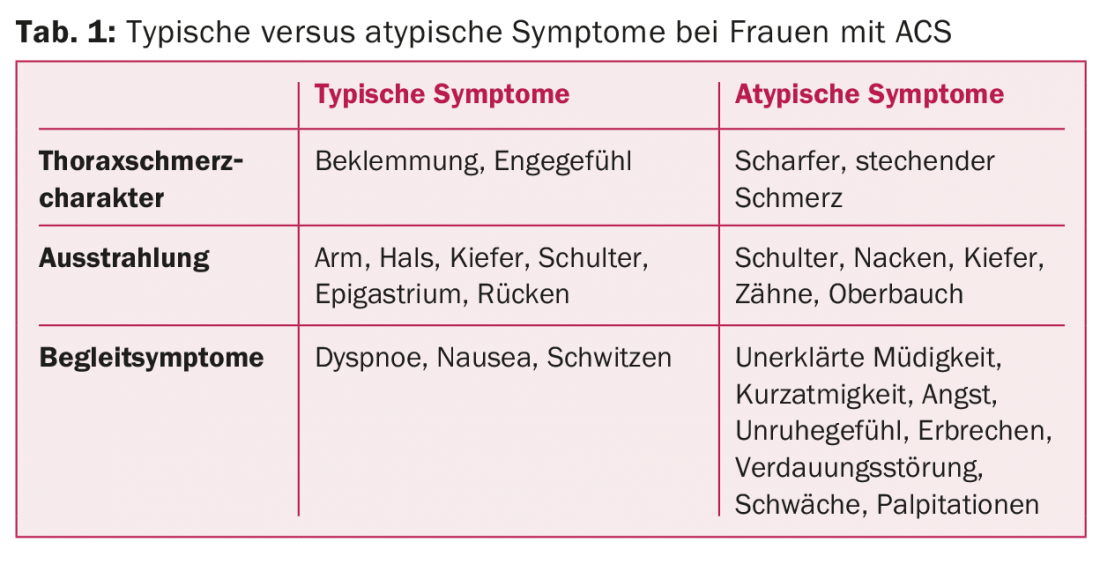

There are evidenced gender differences in the clinical manifestation of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Up to one-third of patients often have atypical complaints (Table 1) [13].

The atypical clinical picture has consequences for the correct triage and timely diagnosis (ECG, laboratory) of ACS and the initiation of adequate therapy.

The variation in clinical presentation partly explains the delay in initiating adequate therapy. It is well documented that a loss of time to interventional coronary revascularization leads to a worse outcome in terms of morbidity and mortality [14].

Therapy of coronary heart disease

Percutaneous coronary angioplasty is the treatment of choice for lesions requiring revascularization in both sexes. Data from the AMIS Plus Registry (national registry of the Swiss societies of cardiology, internal medicine, and critical care medicine) show that once women were diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction, they received the same evidence-based therapy as men. Overall mortality has been reduced by 50% over the past 15 years, particularly in ST elevation infarcts, thanks to rapid reperfusion therapy.

However, the poorer prognosis in women with myocardial infarction can be explained both by the significant delay in hospital presentation with correspondingly later initiation of therapy and revascularization and by the more frequent poorer clinical condition at admission or before initiation of therapy. Women wait too long to call the ambulance.

Women are also at higher risk of experiencing a drug side effect than men due to differences in body weight, volume of distribution, different mechanisms of degradation, and genetic polymorphisms.

In women with heart disease, compliance regarding medication use is even worse than in men: after one year, 59% of female patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) are still taking statins (versus 82% in men), 53% are taking beta-blockers for heart failure (versus 60%), and 54% are taking ACE inhibitors (versus 60%) [15]. Statins are at least as effective for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease in women as in men [16].

The use of aspirin in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease is undisputed. However, the use, or benefit, in primary prevention in women is even more controversial than in men [17].

Data from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) also indicate a significantly higher risk of bleeding of more than 43% during hospitalization for ACS. Bleeding occurs at the puncture site primarily femorally, this also in association with higher doses of antiplatelet drugs [18]. Thus, the radial approach is probably the safer approach to reduce severe bleeding complications, at least this is true for acute coronary syndrome.

Rehabilitation for heart disease

Women are less likely to be enrolled in rehabilitation. The sustainable benefit of a specifically cardiac rehabilitation is equally valid for women, especially in the patients with a pronounced risk profile according to all international guidelines [19]. Often an additional family burden and special psychosocial stress situations play a role, which is why participation in rehabilitation is not possible.

Depressive syndromes are significantly more common in women than in men and require specialized care.

Cardiovascular risk factors

The two sexes show a different risk profile. Women are on average 8-10 years older than men at manifestation of CHD. At the same time, women are more likely to have multiple risk factors.

The known risk factors are the same for both sexes, except that susceptibility is very likely greater in women. Tobacco use, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obesity are potent risk factors in women [20–22].

The association of acute myocardial infarction with arterial hypertension is also stronger in women than in men [23].

Regarding dyslipidemia, no significant gender differences are known.

Menopause – the dilemma with hormones

Especially after menopause, cardiovascular risk increases more rapidly.

The increased cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women is not explained by lower estrogen levels alone.

The complex effect of estrogen replacement in relation to increasing cardiovascular risk after menopause, is not fully understood. The cardioprotective effect of endogenous estrogen cannot be supplied by exogenous hormone replacement during menopause [24,25].

Pregnancy and arterial hypertension

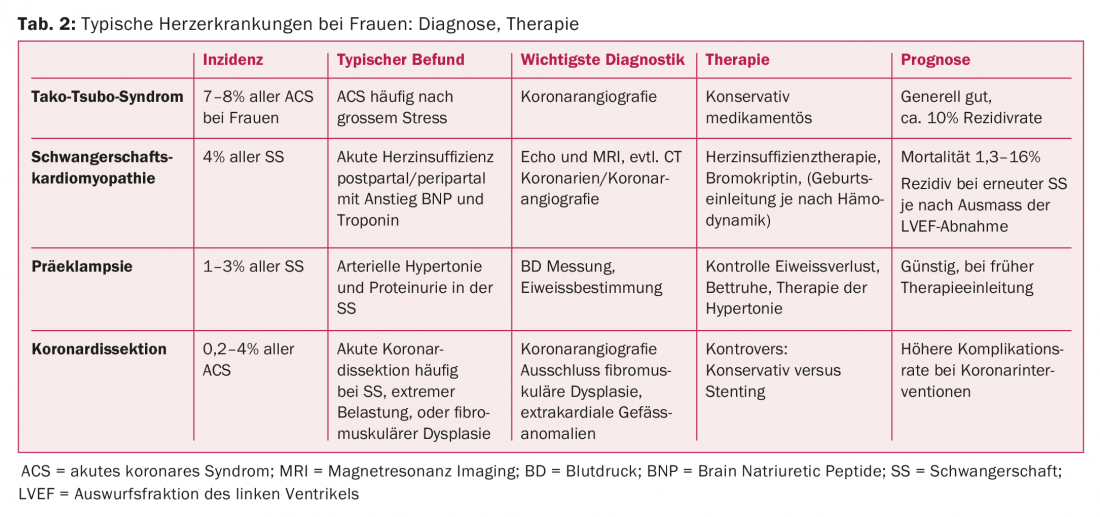

Pre-eclampsia, defined as pregnancy-induced arterial hypertension accompanied by proteinuria, occurs in 1-2% of all pregnancies (Table 2) . Current data indicate a twofold increased cardiovascular risk. The risk of developing arterial hypertension or diabetes mellitus later in life increases twofold and threefold, respectively [26,27]. It is imperative that women with pre-eclampsia conditions be evaluated six months postpartum for cardiovascular risk.

Pregnancy-induced arterial hypertension affects approximately 15% of all pregnancies, making it not all that uncommon in practice. Cardiovascular risk is also increased, but less pronounced than after pre-eclampsia. The diagnosis of arterial hypertension is also significantly more common during the course; the risk of developing diabetes mellitus is also likely to be increased, although the evidence here is not well established. This leads to the recommendation to screen these patients regularly in the later course. [28].

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) affects about 5% of all women of childbearing age. These women are very likely to have an increased risk of developing arterial hypertension, but the available data on this are conflicting. However, there is an established association with the development of diabetes mellitus, so regular screening of these women is certainly warranted [28].

Pregnancy Cardiomyopathy

Gestational cardiomyopathy (Table 2) occurs in approximately 1 in 2000 births and is clustered in patients with arterial hypertension, preeclampsia, and older age. It is a potentially life-threatening acute heart failure, often occurring in the first week after delivery, with no previous evidence of heart disease. Diagnosis is based on three criteria: Echocardiographic evidence of impaired left ventricular pump function of <45%, development of heart failure in the last month of pregnancy, or within a few months postpartum, and the absence of any other cause of heart failure. A relationship with prolactin levels seems to exist, which is why the administration of bromocriptine plays some role. The exact etiology of pregnancy cardiomyopathy remains unclear; however, a recent paper showed that the same genetic alterations may be present in pregnancy cardiomyopathy as in dilated cardiomyopathy [29]. It is important to diagnose and accordingly induce labor depending on the hemodynamic state. About half of all women with peripartum cardiomyopathy recover within six months of giving birth. After delivery, heart failure therapy should be initiated. To date, it is unclear whether breastfeeding delays or promotes regression of cardiac changes; studies on this are pending.

There is no general consensus for recurrence risk in future pregnancies. The risk of recurrence after complete recovery of LVEF is approximately 20%. Individualized care and counseling is indicated for these high-risk patients [30,31].

Arterial hypertension

High blood pressure is a common problem in clinical practice. The frequency increases with age, in women even more than in men. Arterial hypertension remains one of the most common risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in both sexes [32].

Treatment of blood pressure improves cardiovascular risk. Although women are mostly underrepresented in the available randomized trials. Subgroup analyses indicate that both sexes benefit equally from optimal blood pressure reduction.

Obese women have a 4-6-fold increased risk compared with normal-weight women of developing arterial hypertension [33]. Oral contraceptives can also lead to an increase in blood pressure. However, with the new generation of combined contraceptives, much lower doses of estrogen and progestin are supplied, which means that there is only a small risk of a relevant increase in blood pressure. An association of contraceptive use with increased risk of myocardial infarction could not be confirmed.

In women who already have a diagnosis of arterial hypertension, as in men, careful monitoring and optimal therapy should be provided.

Autoimmune diseases: an underestimated cardiac risk factor.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are more common in women. The chronic inflammatory state accelerates atherogenesis, leading to increased cardiovascular mortality in patients with RA and SLE [34].

The Framingham Risk Score substantially underestimates cardiovascular risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in both men and women. Based on this, a simple multiplier of 1.8 was proposed by the professional society (EULAR) to start primary prophylaxis earlier.

Annual cardiac screening is suggested in patients with these autoimmune diseases because of the high cardiovascular risk and high inflammatory disease activity. Otherwise, screening will be done every two to three years [35].

Tako-Tsubo syndrome

Tako-Tsubo syndrome is a stress cardiomyopathy (“broken heart syndrome”) first described in Japan in the 1990s, where release of catecholamines, spasm, and microvascular dysfunction are thought to result in the clinical picture of acute myocardial infarction, despite open epicardial vessels (Table 2). Mainly postmenopausal women are affected [36]. Triggers may include death and serious illness in the family, an argument, a lecture, physical stress, serious illness, cocaine, and anesthesia [37].

Up to 7.5% of women have Tako-Tsubo syndrome as a cause of acute coronary syndrome. An example of the typical image in the laevogram in coronary angiography is shown in Figure 1. The risk of recurrence is approximately 2% per year. This acute heart failure syndrome has substantial morbidity and mortality. Which therapy is best here remains unresolved [38].

Coronary dissections

Spontaneous coronary dissections are much more common in women. Coronary artery dissections are clustered after extreme physical or psychological stress and during pregnancy or peripartum (Table 2). It can also affect multiple vessels, but most commonly the RIVA territory. Figure 2 and 3 shows an example of a young woman with acute coronary syndrome with transmural ischemia in the RIVA area; the cause was found to be coronary dissection. The risk of recurrence is up to 29% [39]. Possible causes mainly include fibromuscular dysplasia; rarely, congenital connective tissue weakness such as Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan syndrome may be responsible [40]; coronary angiography is recommended. Whether the dissection should be treated conservatively or by dilatation and stenting remains controversial.

Summary

When treating women with heart disease on a day-to-day basis, we must be aware of the following limitation: Our clinical practice and current guidelines regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment are based on randomized trials with a small number of women versus the predominantly male patient population. Yet, thanks to gender studies, we have gained increased insight into how to optimally treat women with ACS, coronary artery disease, and hypertension.

Women’s cardiovascular health depends on several gender-specific factors. Hormonal influences as well as pregnancy-related factors and autoimmune diseases can increase cardiovascular risk.

Certain conditions, such as Tako-Tsubo syndrome, coronary artery dissection, and pregnancy cardiomyopathy, are women-specific conditions whose specific presentation, workup, and therapy are important.

Recognition of such gender-specific risk factors is essential for adequate therapy initiation. Considering the above points, women with heart disease can be optimally evaluated, clarified and treated.

Literature:

- Bairey Merz CN, et al: WISE Investigators. Insights from the NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study, part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47(suppl): S21-S29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.084.

- Basso C, et al: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a neglected cause of acute myocardial ischaemia and sudden death. Heart 1996; 75: 451-454.

- DeMaio SJ Jr, et al: Clinical course and long-term prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol 1989; 64: 471-474.

- Thompson EA, et al: Gender differences and predictors of mortality in spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a review of reported cases. J Invasive Cardiol 2005; 17: 59-61.

- Selzer A, et al: Clinical syndrome of variant angina with normal coronary arteriogram. N Engl J Med 1976; 295: 1343-1347.

- Shaw LJ, et al: Women and ischemic heart disease: evolving knowledge. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: 1561-1575.

- Shaw JL, et al: Insights from the nhlbi-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation study: part i: gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47: S4-20.

- Lidegaard O, et al: Thrombotic stoke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med 2012; 14: 366: 2257-2266.

- Farb A1, et al: Coronary plaque erosion without rupture into a lipid core. A frequent cause of coronary thrombosis in sudden coronary death. Circulation 1996; 93(7): 1354-1363.

- Virmani R, et al: Lessons from sudden coronary death: a comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000; 20: 1262-1275.

- Virmani R, et al: Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47(suppl): C13-C18. doi: 10.1016/j. jacc.2005.10.065.

- Vrints CJ: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Heart 2010; 96: 801-808.

- Khan NA, et al: GENESIS PRAXY Team. Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome symptom presentation in young patients. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1863-1871.

- Ting HH, et al: Factors associated with longer time from symptom onset to hospital presentation for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 959-968.

- Manteuffel M, et al: Influence of patient sex and gender on medication use, adherence, and prescribing alignment with guidelines. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014; 23(2): 112-119.

- The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomized trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994; 344: 1383-1389.

- Ridker PM, et al: A Randomized Trial of Low-Dose Aspirin in the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1293-1304.

- Moscucci M, et al: Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 1815-1823.

- Piepoli MF, et al: Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation: a position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010; 17: 1-17.

- Njølstad I, et al: Smoking, serum lipids, blood pressure, and sex differences in myocardial infarction: a 12-year follow- up of the Finnmark Study. Circulation 1996; 93: 450-456.

- Kawachi I, et al: Smoking cessation in relation to total mortality rates in women: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119: 992-1000.

- Willett WC, et al: Relative and absolute excess risks of coronary heart disease among women who smoke cigarettes. N Engl J Med 1987; 317: 1303-1309.

- Yusuf S, et al: Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 2004; 364: 937-952.

- Hulley S, et al: Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and estrogen/progestin replacement study (hers) research group. JAMA 1998; 280: 605-613.

- Grady D, et al: Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: heart and estrogen/progestin replacement study follow-up (HERS II). JAMA 2002; 288: 49-57.

- Engeland A, et al: Risk of diabetes after gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. A registry-based study of 230,000 women in Norway. Eur J Epidemiol 2011; 26: 157-163.

- Lykke JA, et al: Hypertensiveregnancy disorders and subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the mother. Hypertension 2009; 53: 944-951.

- European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice European Heart Journal 2016; 37: 2315-2381.

- Ware JS, et al: IMAC-2 and IPAC Investigators. Shared Genetic Predisposition in Peripartum and Dilated Cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(3): 233-241.

- Arany Z, et al: Peripartum Cardiomyopathy Circulation 2016; 133(14): 1397-1409.

- Pearson GD, et al: Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases. JAMA 2000; 283:1183-1188.

- Weyer GW, et al: Hypertension in Women, Evaluation and Management. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 2016; 43(2): 287-306.

- Bateman BT, et al: Hypertension in women of reproductive age in the United States: NHANES 1999-2008. PLoS One 2012; 7: e36171.

- Crowson CS, et al: Usefulness of risk scores to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Cardiol 2012; 110: 420-424. 42430X Kyuma M, et al: Effect of intravenous propranolol on left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis (ampulla cardiomyopathy): three cases. Circ J 2002; 66: 1181-1184.

- Peters MJ, et al: EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 325-331.

- Brenner R, et al: Clinical characteristics, sex hormones, and long-term follow-up in Swiss postmenopausal women presenting with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol 2012; 35(6): 340-347.

- Akashi YJ, et al: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation 2008; 118: 2754-2762.

- Templin C, et al: Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(10): 929-938.

- Tweet MS, et al: Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2012; 126: 579-588.

- Henkin S, et al: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection and its association with heritable connective tissue disorders. Heart 2016; 102(11): 876-881.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(6): 16-23