Malignant or premalignant mucosal changes of the gastrointestinal tract can usually be curatively removed endoscopically. Endoscopic resections are based on many technical innovations; the resections are safe and allow a definitive diagnosis and prognosis. A large number of surgical procedures can be prevented by endoscopic resection. At the same time, endoscopic resection allows a very good selection of patients who really need surgery. Endoscopic resections are rare procedures, belong to “highly specialized medicine” and should be limited to a few specialists.

Tumors of the tubular gastrointestinal tract represent a substantial proportion of malignancies. These tumors arise from dysplasias of the mucosal surface in all sections of the digestive tract, beginning at the mouth and extending to the anus. The dysplasias are sometimes only detectable histologically, but in many cases they are also visible endoscopically, especially when modern equipment and staining techniques are used. Endoscopic access allows early detection and local treatment of malignant and premalignant changes. This great advantage over solid organs can and should be exploited.

Endoscopy of the gastrointestinal tract has changed from a diagnostic tool to a method with very effective therapeutic possibilities. The basis for this was, on the one hand, the tremendous improvements in optical qualities, which were the prerequisite for the detection and demarcation of lesions, and, on the other hand, many additional devices that enable safe resection.

The endoscopic techniques of resection

Endoscopic resection essentially consists of removing changes in the mucosa by separating it in the submucosal layer without causing perforation. This is possible because the connective tissue of the submucosa allows easy separation of the mucosa from the muscle layer, the muscularis propria. Decades ago, people began using an electric snare to remove polyps confined to the mucosa from the colon. The technique was initially limited to small polyps, but now areas of ten or more centimeters can be removed from the esophagus, stomach, colon, and rectum. Snare resection has been extended by so-called endoscopic mucosal resection procedures: endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Endoscopic solid wall resections represent another development.

Instead of resection, altered mucosa can also be removed by ablative procedures. In this process, the mucosa is destroyed by means of thermal energy. This can be applied as photodynamic energy, radiofrequency or cryotherapy. The main disadvantage is that a complete histology of the tissue cannot then be performed.

What can and should be resected endoscopically?

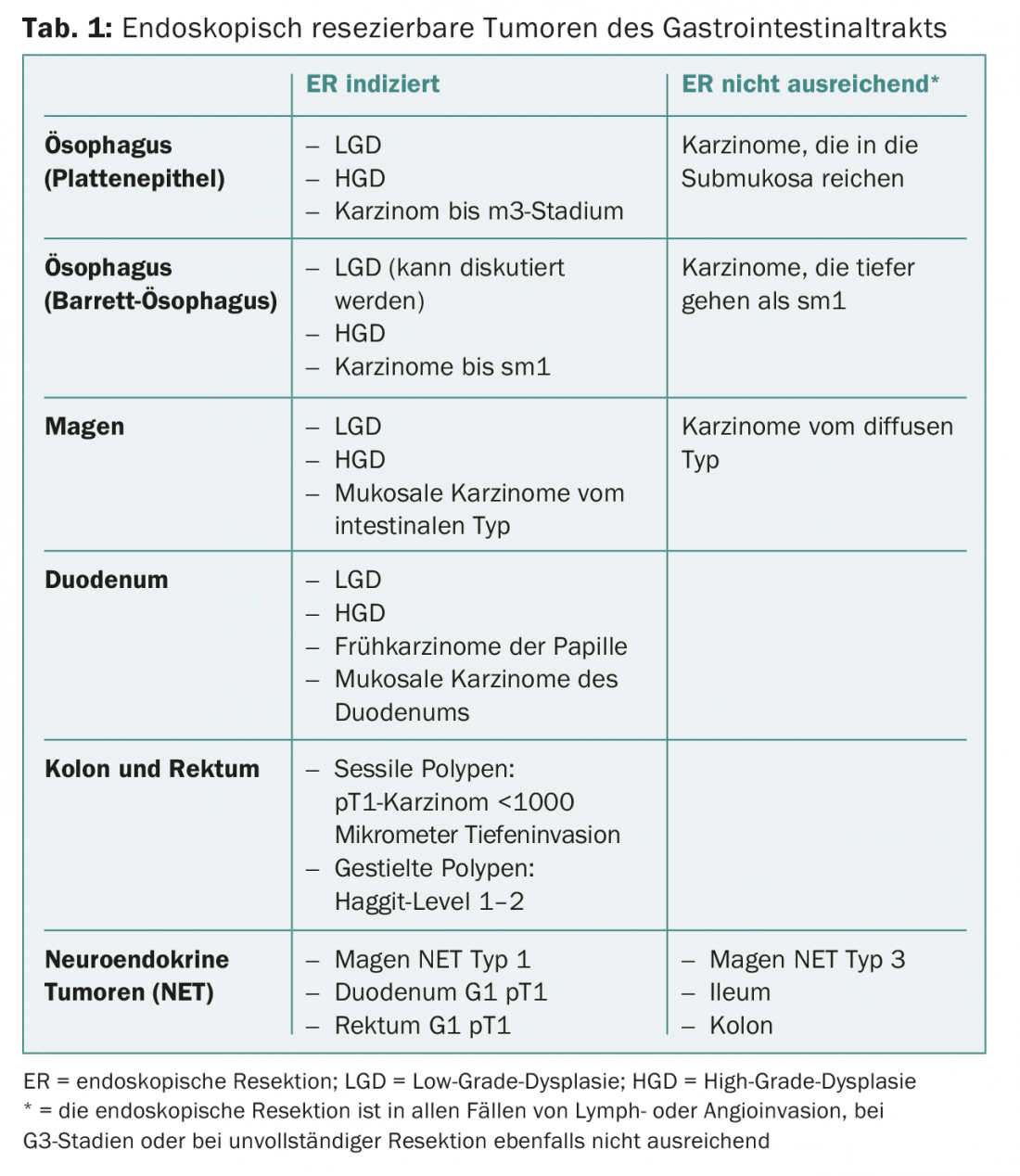

Endoscopic resection should be offered for the treatment of all dysplastic mucosal lesions throughout the tubular gastrointestinal tract, whether low- or high-grade dysplasia. Pre-existing carcinomas can be resected endoscopically if they are confined to the mucosa. Depending on the organ and type of carcinoma, those with invasion of the submucosa can also be correctly removed oncologically by endoscopy (Table 1).

Deeper penetrating carcinomas usually require oncologically correct surgical resection with removal of regional lymph nodes, as their involvement increases in frequency proportionally with depth of penetration. With the newly available full-wall resection, even higher-grade carcinomas could be completely removed. However, because of the lack of lymph node removal, this is only an option for patients in whom proper surgical resection is too risky. However, in these patients, the method is a very attractive minimally invasive technique.

The techniques of mucosal resection were developed for early carcinomas that extend only slightly beyond the mucosal surface in thickness. However, especially in the colon, early carcinomas can be hidden in sometimes very voluminous polyps. Endoscopic resection of these polyps has been limited by their size. In particular, the risks for bleeding and perforation limited endoscopic resection. Newer techniques now allow prevention of perforation and bleeding, so that even very large colonic polyps can be resected safely.

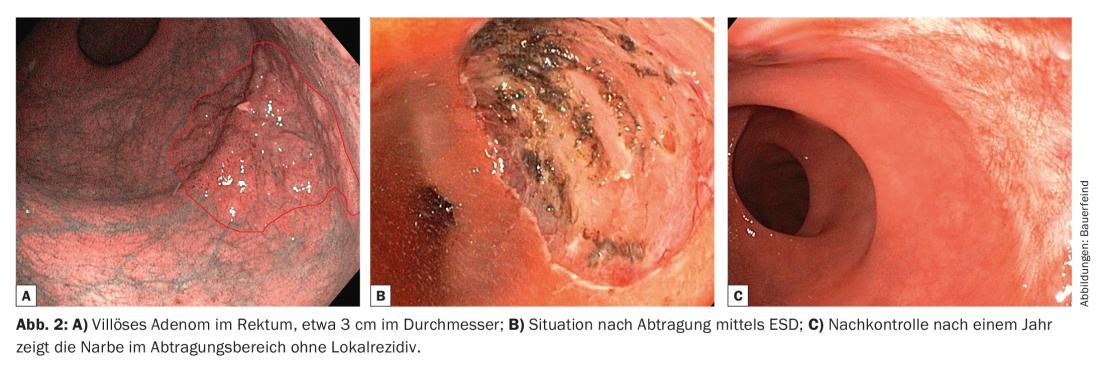

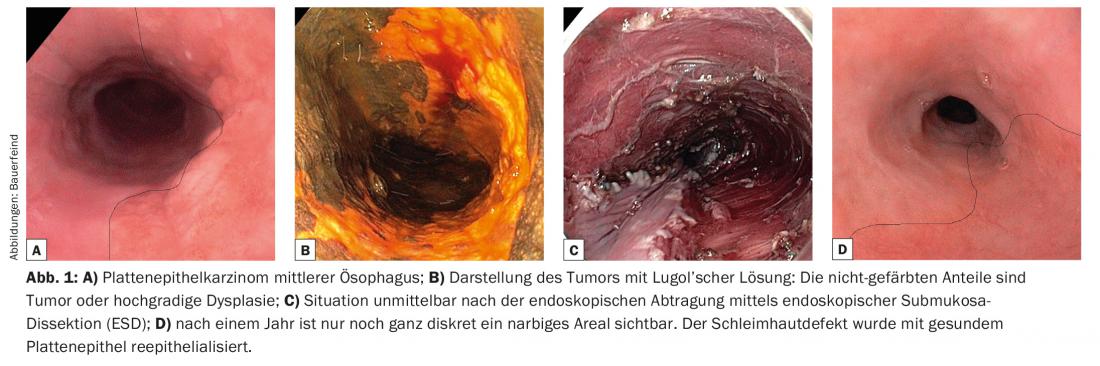

Examples of resections in different sections of the gastrointestinal tract are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Advantages and risks of endoscopic tumor resection

The most important advantage of endoscopic resection is, of course, that it avoids much more invasive and expensive surgical therapy. However, the exact staging of the dysplasia or presumed early carcinoma is usually unknown prior to surgery. Only a complete endoscopic resection of a luminal pathology allows the correct histological classification. Thus, in addition to a possible complete cure, endoscopic resection allows, above all, accurate diagnosis. In many cases, this revises the prior biopsy diagnosis, usually upward. Thus, from the endoscopic resections of high-grade dysplasia of Barrett’s esophagus, which are now routinely performed, it is known that after endoscopic resection, in up to 30% of cases there was actually already a previously unknown carcinoma. Thus, histologic staging correct after endoscopic resection allows a decision to be made as to whether oncologically sufficient treatment has already been given or whether additional surgical therapy, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy is necessary.

The main risk of endoscopic resection is perforation during or after the procedure. Perforation converts, at least formally, a previously lumen-confined carcinoma into a T4 carcinoma. In some cases, this leads to unnecessarily aggressive therapeutic follow-up. However, it should be said that there are too few data demonstrating relevant prognostic deterioration in these cases. Theoretically, one could also assume that mechanical manipulation of a carcinoma – something surgeons avoid as much as possible – leads to higher metastasis. However, according to the large number of data from endoscopically resected colon polyps, this does not seem to be the case. Nevertheless, the prevention of perforation should be a very important goal of the endoscopically active gastroenterologist. Should a perforation occur, he must be able to manage it endoscopically.

Who should perform endoscopic resections?

Endoscopic mucosal resections are rare procedures. They concern tumors such as esophageal carcinoma, the treatment of which by surgeons is now fortunately restricted by the regulations of highly specialized medicine to a few centers with sufficiently high case numbers. The gastroenterologist’s curriculum does not include training in endoscopic resection techniques. However, work is underway to develop training regulations for interventional gastroenterologists. Similar to surgical procedures, success in endoscopy is defined by the number of cases. In the absence of official regulations, it is the responsibility of referring physicians to support limitation to a few centers.

Long-term results of endoscopic tumor resection.

There are no randomized trials comparing surgical therapy with endoscopic therapy for any of the early intestinal cancers. Taking historical comparisons, tumor-free survival seems to be equivalent with both methods. The advantage of endoscopy is significantly lower postoperative mortality and morbidity. Randomized trials are unlikely to continue in the future as endoscopic methods become more widely accepted. In addition, there is quite a disparity between surgery and endoscopy in terms of degree of invasiveness; it may be difficult to randomize patients. Endoscopic resection should also be seen as the first step before surgery, if necessary. Therefore, close and harmonious cooperation between the two highly specialized disciplines is desirable for the optimal care of these patients.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(4): 26-28.