With increasing age, systolic blood pressure rises continuously, whereas diastolic blood pressure rises until the sixth decade of life and then falls again. Thus, in old age, isolated systolic hypertension occurs quite predominantly. In general, antihypertensive therapy in elderly patients is warranted on the basis of the evidence. However, especially in this population, the decision for or against antihypertensive therapy must always be made in the overall medical context. Lifestyle modifications are also the basis of antihypertensive therapy in elderly patients. However, weight reduction is not advisable in every case, since muscle loss at an older age often has adverse consequences and is often irreversible. Diuretics and calcium antagonists have been best studied in isolated systolic hypertension. Nevertheless, the choice of drug therapy should primarily be based on existing comorbidities. Basically, “Start low, go slow!”

Arterial hypertension remains the major risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity worldwide. In Switzerland, their prevalence is approximately 30-35%, and with increasing age, the prevalence increases up to 70% [1].

17% of the Swiss population is currently over 65 years old. Forecasts of the Federal Statistical Office speak of about 2.1 million people over 65 years and about 685,000 people over 80 years in 2030 [2]. This is also expected to result in a massive increase in the prevalence of arterial hypertension. This differs in important ways in the elderly from hypertension in younger people. This is of essential importance with regard to both diagnostics and therapy.

In the following, the currently available evidence on the diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension in the elderly will be presented.

When is one actually old?

When one is “old” is not universally defined. The United Nations defines “old” as being over 60 years of age, in Africa one is already “old” at 50, and in Switzerland one is considered “old” from the retirement age of 65 [3]. Like the official definitions, the use of the term “old age” in the medical literature is inconsistent. The terms “young old” (60-69 years), “middle old” (70-79 years), “very old” (≥80 years), or “young old” (65-74 years), “old” (75-84 years), and “old old” (≥85 years) are often used here [4,5].

In view of a growing group of older people who lead an active life for many years after retirement and often show signs of mental and/or physical impairment or frailty relatively late, it is obvious to define age not only by the number of years of life [6].

Including this aspect, old age is defined rather by the loss of ancestral roles or the potential for assuming new roles in society and, more generally, by the loss of individual potential to participate or actively participate in social life [3].

Hypertension in the elderly – different from the younger patient

With increasing age, systolic blood pressure rises continuously in both men and women, whereas diastolic blood pressure rises until the sixth decade of life and then falls again. This is the reason why isolated systolic hypertension is observed quite predominantly in old age [7]. Responsible for this are fibrotic processes in the vessel wall with loss of elastic extensibility especially of the large vessels, increase of pulse wave velocity and thus increase of systolic blood pressure [8].

The autonomic circulatory dysregulation frequently observed in old age favors the development of orthostatic hypotension, but also hypertension. While the former is associated with an increased risk of falls, syncope, and cardiovascular events, the latter promotes the development of end-organ damage such as left ventricular hypertrophy, coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular disease, and also worsens blood pressure control [8].

Furthermore, increased glomerus sclerosis and interstitial renal fibrosis are observed with increasing age. In sum, this development leads to a decrease in glomerular filtration rate, increase in intracellular sodium content, reduced Na-Ca exchange, and ultimately volume expansion. In addition, microvascular damage contributes to the chronic renal failure commonly observed in old age. Reduction of renal tubules limits the renal excretory capacity for potassium, which is an important etiologic factor for the hyperkalemia frequently observed in the elderly [8].

Last but not least, secondary hypertension (e.g., as a consequence of hyperaldosteronism, thyroid dysfunction, atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis) is observed more frequently in older patients than in younger ones. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome also promotes the development of arterial hypertension in old age. Lifestyle (exercise, smoking, alcohol) as well as polypharmacy, which is frequently observed especially in old age, also play an important role, which is why the intake of potentially blood pressure-increasing drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, hormones, calcium and/or herbal remedies and vitamin preparations should always be inquired about [8].

Is there a benefit to antihypertensive therapy in the aged?

Numerous studies show that treatment of isolated systolic arterial hypertension, which as mentioned is mainly observed in the elderly, can reduce the incidence of stroke, cardiovascular events, death, and even all-cause mortality [9]. This beneficial effect could be shown in people over 65 years of age not only for the thiazide diuretics or calcium antagonists used in early studies, but also for “more modern” substance groups such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers [10]. Strictly speaking, however, these results are not applicable to those over 80 years of age, as this age limit was an exclusion criterion in almost all studies. However, subanalyses suggested that this group of patients also benefits from blood pressure lowering in terms of stroke and heart failure risk reduction [11].

Direct evidence exists only since the publication of the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET), in which antihypertensive therapy with indapamide ± perindopril was compared with placebo. Systolic blood pressure at inclusion had to be between 160 and 199 mmHg. Exclusion criteria were blood pressure >220/110 mmHg on therapy, use of more than one additional antihypertensive drug for more than 3 months, secondary hypertension, history of stroke or heart failure, and renal insufficiency (creatinine ≥150 μmol/l) or hypo-/hyperkalemia. The target blood pressure was <150/80 mmHg. HYVET was discontinued early because the risk of heart failure and also all-cause mortality were significantly reduced in the group treated with indapamide ± perindopril. In addition, there were clear trends toward reduced stroke risk and reduced cardiovascular and stroke mortality [12].

In other studies, antihypertensive therapy at least slowed the development of dementia and reduced the risk of falls in elderly patients [13,14]. Therefore, based on the available evidence, antihypertensive therapy in the elderly patient is not only justified but should always be attempted, with few exceptions.

Diagnostic recommendations

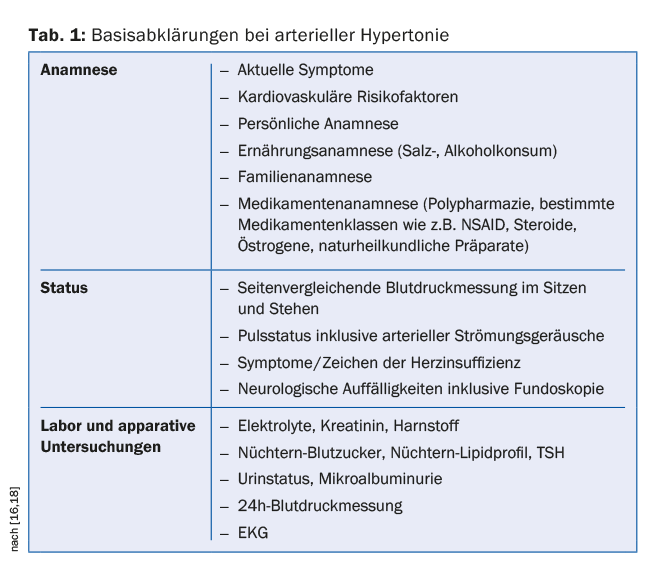

The diagnostic procedure in elderly patients does not differ significantly from that in younger patients. Objectives are to detect and grade arterial hypertension, to determine etiology (primary vs. secondary), and to comprehensively assess other cardiovascular risk factors and hypertensive end-organ damage. Especially in elderly patients, the current medication and dietary habits should also be determined in detail. 24-h blood pressure measurement should be performed generously in this group of patients, as this allows diagnosis of not only hypertensive but also hypotensive phases (e.g., in the context of autonomic dysregulation). Many antihypertensive drugs are eliminated renally, so a complete workup should include determination of electrolytes and creatinine, including glomerular filtration rate. Secondary hypertension is more common in older patients than in younger patients. Leading among these are renal artery stenosis, renal hypertension, and thyroid dysfunction [15]. Table 1 summarizes the basic investigations [16].

Therapy recommendations

In both younger and older patients, lifestyle modifications are the foundation of antihypertensive therapy. This includes abstinence from nicotine and, if necessary, a reduction in alcohol consumption, a diet rich in vegetables and fruits, and regular physical activity. Salt restriction to <6 g/d seems to be particularly effective [17]. On the other hand, weight reduction is not advisable in every case, since muscle loss often has detrimental consequences, especially at an advanced age, and is often irreversible.

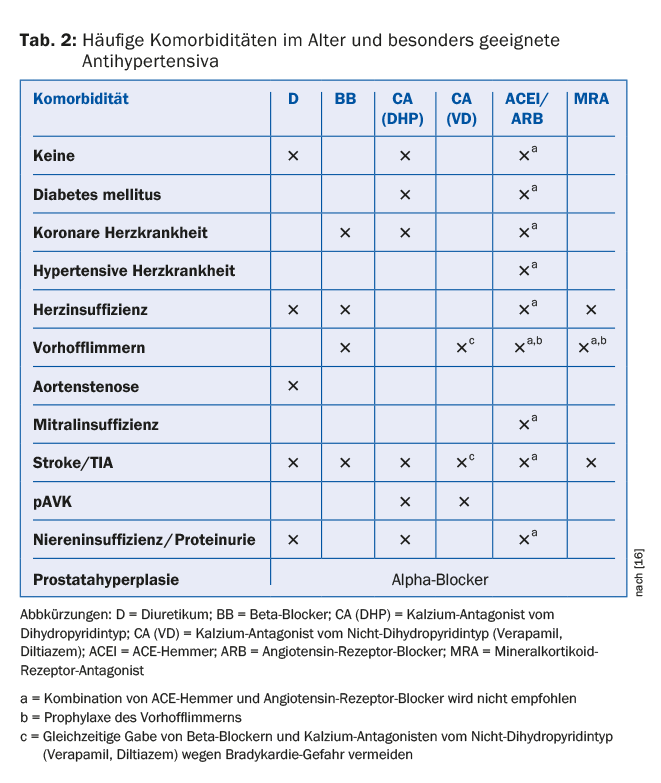

Elderly patients usually have an increased basal cardiovascular risk due to frequent preexisting comorbidities, which often necessitates the immediate initiation of antihypertensive therapy in accordance with international guidelines. Diuretics and calcium antagonists have been best studied in isolated systolic hypertension. Nevertheless, the choice of drug therapy should primarily be based on existing comorbidities [18]. Table 2 summarizes the antihypertensives recommended for the most common comorbidities [16].

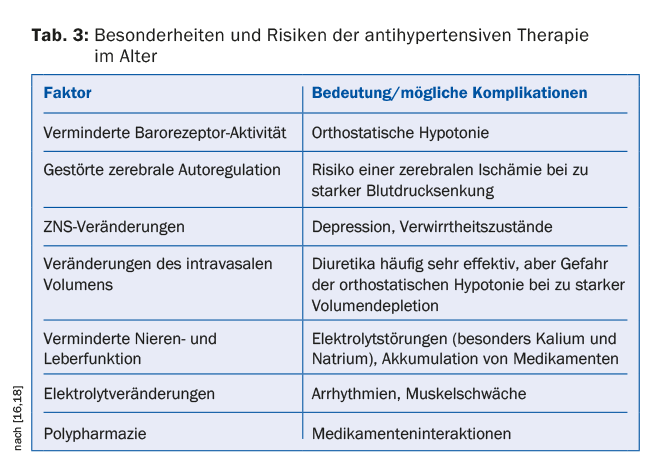

In addition, various physiological peculiarities must be observed, especially in elderly patients (tab. 3) . The therapy should be started with low doses and slowly increased (“Start low, go slow!”). Patients should undergo regular and close clinical monitoring. During the adjustment phase, in case of dose changes or diseases that may be associated with volume depletion (e.g. gastrointestinal diseases, febrile infections), regular and close-meshed monitoring of renal function and electrolytes and, if necessary, appropriate adjustment of the therapy should be performed, especially when diuretics, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers are administered [18].

Blood pressure reduction in the elderly patient – from when and how far?

In patients younger than 80 years of age without significant comorbidities, current guidelines recommend antihypertensive therapy at a systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg. The same applies to those over 80 years of age without evidence of frailty, starting with a systolic blood pressure of ≥160 mmHg. In principle, all substance groups can be used to lower blood pressure, although in isolated systolic hypertension the blood pressure-lowering and organ-protective effects of antihypertensive therapy are best demonstrated for diuretics and calcium antagonists.

Therapies that have already been started and are well tolerated can and should be continued unchanged after the age of 80 [18]. The current recommended blood pressure target for those over 80 years of age is 140-150 mmHg systolic, and for those under 80 years of age and well tolerated, <140 mmHg systolic.

Target values for diastolic blood pressure have not yet been defined. However, there is evidence that diastolic blood pressure should not be lowered below 65-70 mmHg in the elderly because further blood pressure lowering may increase cardiovascular mortality [19,20].

In contrast to elderly patients without significant comorbidities, the benefit of antihypertensive therapy in frail patients is not clearly established. Frailty is characterized by reduced physical strength and endurance, as well as impairment of physiological functions, and is associated with increased risk of addiction and death [21]. The presence of frailty or “frailty” can be assessed, for example, by a 6-meter walk test. Here, the patient walks as fast as possible over a distance of 6 meters. At a walking speed <0.8 m/s or failure to walk the 6-meter distance, normal blood pressure appears to be associated with a worse prognosis compared with elevated blood pressure [18,22]. In this situation, the indication for antihypertensive therapy should certainly be made cautiously. Furthermore, especially in elderly patients, the decision for or against antihypertensive therapy should always be made in the overall medical context.

Literature:

- Wolf-Maier K, et al: Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure level in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA 2003; 289: 2363-2369.

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Future Population Development. www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/01/03/blank/key/ind_erw.html (last accessed 01.11.2015).

- WHO: Health statistics and information systems. www.who.int/healthinfo (last accessed 01.11.2015).

- Zizza CA, Ellison KJ, Wernette CM: Total water intakes of community-living middle-old and oldest-old adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009 Apr; 64(4): 481-486.

- Cicirelli VG: Older Adults’ Views on Death. Springer 2002.

- Torpy JM: Frailty in older adults. JAMA 2006; 296: 2280.

- Chobanian AV: Clinical practice. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. New Engl J Med 2007; 357: 789-796.

- Aronow WS, et al: ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly. Circulation 2011; 123: 2434-2506.

- Staessen JA, et al: Risks of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet 2000; 355: 865-872.

- Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration: Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomized trials. BMJ 2008; 336: 1121-1123.

- Gueyffier F, et al: Antihypertensive drugs in very old people: a subgroup meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. INDIANA Group. Lancet 1999; 353: 793-796.

- Beckett NS, et al: Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1887-1898.

- Igase M, Kohara K, Miki T: The association between hypertension and dementia in the elderly. Int J Hypertens 2012; 2012: 320648. DOI: 10.1155/201/320648.

- Gangavati A, et al: Hypertension, orthostatic hypotension, and the risk of falls in a community-dwelling elderly population: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly of Boston study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 383-389.

- Viera AJ, Neutze DM: Diagnosis of secondary hypertension: an age-based approach. AmFam Physician 2010; 82: 1471-1478.

- Schönenberger AW, Erne P, Stuck AE: Arterial hypertension in the elderly. Ther Umsch 2012 May; 69(5): 299-304.

- Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS: Sodium and volume sensitivity of blood pressure. Age and pressure change over time. Hypertension 1991; 18: 67-71.

- The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1281-1357.

- Somes GW, et al: The role of diastolic blood pressure when treating isolated systolic hypertension. Arch Int Med 1999; 159: 2004-2009.

- Denardo SJ, et al: Blood pressure and outcomes in very old hypertensive coronary artery disease patients: an INVEST substudy. Am J Med 2010; 123: 719-726.

- Fried LP, et al: Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Med Sci 2001; 56A: M146-M156.

- Odden MC, et al: Rethinking the association of high blood pressure with mortality in elderly adults: the impact of frailty. Arch Int Med 2012; 172: 1162-1168.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(3): 14-18