The most common triggers of anaphylaxis in adults are drugs and insect bites, and food in children. The development and dynamics of anaphylaxis are unpredictable. According to the WAO recommendation and many international guidelines, epinephrine is considered the drug of choice for anaphylaxis. Corticosteroids have no immediate indication in anaphylaxis. Adrenaline should be administered intramuscularly and not subcutaneously. The initial dose in adults is at least 0.3-0.5 mg (rule of thumb 0.1 mg per 10 kg body weight). There is no absolute contraindication to use epinephrine in anaphylaxis. Allergic general reactions should be followed by allergological clarification in every patient.

Any physician, regardless of specialty, may be faced with an allergic emergency. This is not least because potentially life-threatening reactions are often iatrogenic, i.e. caused by the medical act. Whether in the hospital or in the doctor’s office, at the place of work, at a teaching institute or even at home – everywhere it is important to recognize an acute allergic event so that help can be requested and treatment can be started quickly.

“I don’t think I’ll miss that,” most medically trained people will reply. However, it was recently revealed in Madrid’s Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón that 44% of patients with anaphylaxis admitted to the emergency department had not been diagnosed [1]. Furthermore, after the allergological workup, the cause suspected for the emergency admission had to be revised in 45% of the cases. The survey results were similar for 7822 surveyed physicians and health care professionals. When presented with different clinical scenarios, the correct diagnosis of anaphylaxis was made in only 55% [2]. Thus, the event of anaphylaxis as well as its recognition do not seem to be so simple after all, but remain a medical challenge.

Prevalence and triggers

The number of hospitalizations due to anaphylaxis has increased in Europe, North America, and Australia in recent years. Fortunately, fatalities are relatively rare, so the fatality rate remained stable.

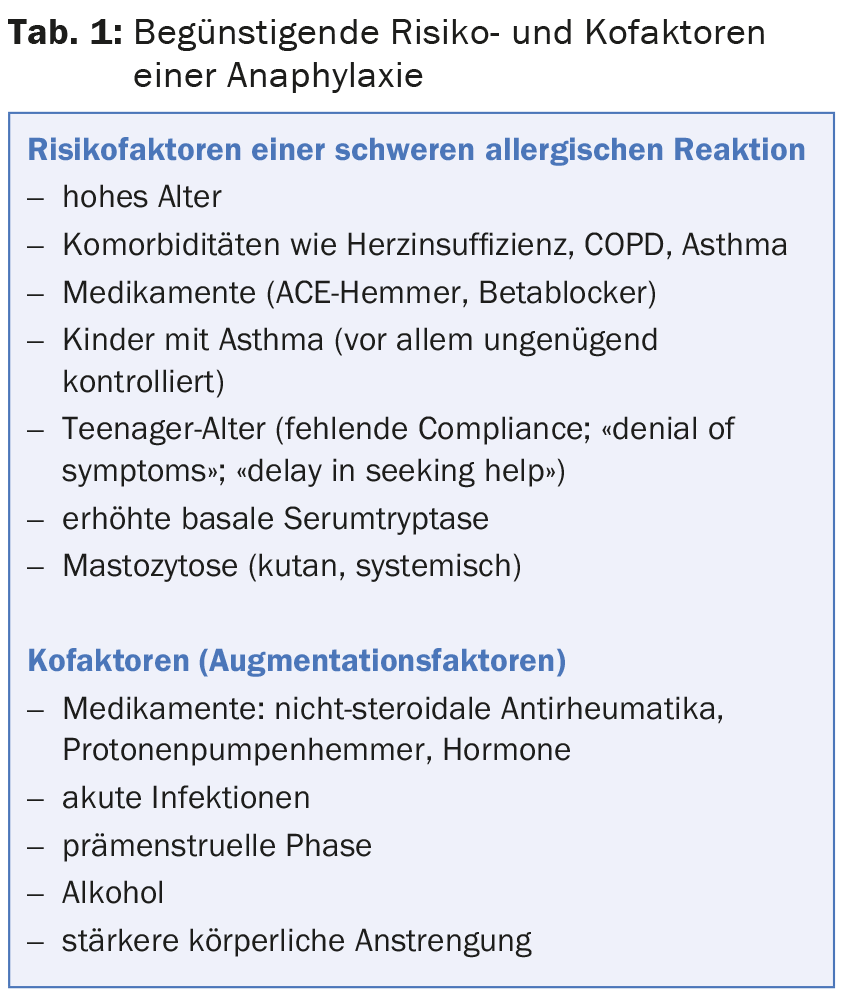

The most common triggers of severe anaphylactic reactions are drugs – especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics – and insect stings (wasps, bees) in adults, whereas in children it is food [3]. Recent studies increasingly point to the importance of risk circumstances, co- and augmentation factors, which provide the impetus for a severe allergic reaction (Tab. 1) [4]. Severe anaphylaxis can occur in patients with mast cell disease such as mastocytosis or elevated basal serum tryptase [5].

Infections (inapperceptions, viral), strong physical exertion (including sexual activity), alcoholic beverages, intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (including metamizole), proton pump inhibitors, but also strong emotional stirrings and stress are common eructable co-factors in anaphylaxis. Exertion-induced anaphylaxis or urticaria is considered a separate entity [6]. In recent years, a food-dependent variant has been described (“food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis” [FDEIA]), which has received attention primarily in connection with the ingestion of wheat products. Some affected individuals were found to be sensitized to the wheat protein omega-5-gliadin (Tri a 19). Atopy is not a prerequisite.

Course and symptoms

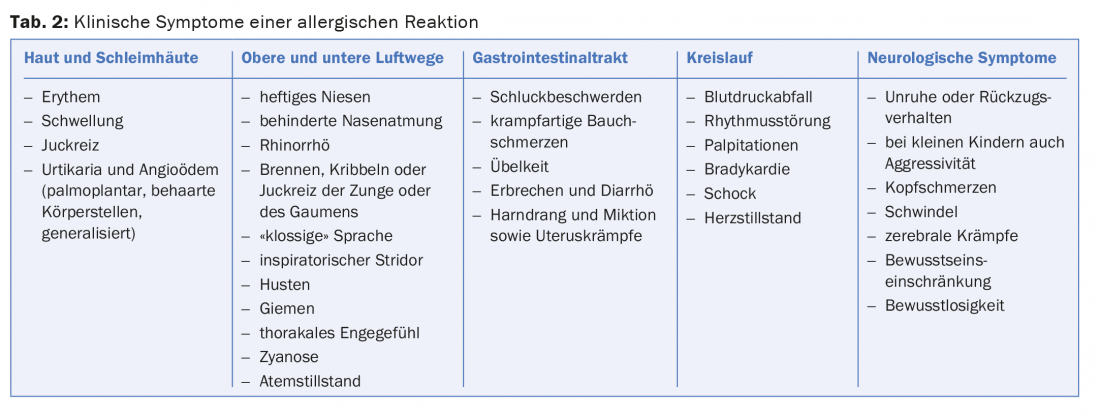

The diagnosis of anaphylaxis is made clinically on the basis of the symptoms with involvement of several organ systems (Tab. 2) . The allergic reaction usually starts rapidly and a short time after contact with an antigen, which is why those affected themselves speak of an “allergy”. Although the integument and mucous membranes are most commonly involved (e.g., generalized pruritus, erythema, urticaria, or angioedema), other organ systems may be affected. Very often the circulatory system is affected with feeling of weakness, tachycardia, dizziness and drop in blood pressure. Respiratory irritation, any form of dyspnea, and also acute gastrointestinal symptoms such as colic or vomiting may be signs of anaphylaxis. It is impossible to predict when the allergic reaction will come to a halt or when cardiac arrest can be expected. Particularly in individuals with mastocytosis, primary circulatory reactions up to and including shock may manifest without cutaneous or pulmonary signs being present. Prodromal symptoms of acute mast cell activation often include palmoplantar or genital itching, a peculiar metallic taste, or even an unexplained feeling of anxiety.

For the verification of an expired mast cell activation, the determination of tryptase from serum helps. The blood sample should be taken one to five hours after a general allergic reaction, regardless of the treatment administered, and compared with a second measurement taken no earlier than one day later. A “normal” tryptase level in the acute stage does not exclude anaphylaxis.

Therapy: the most important drug is adrenaline

The treatment principle of any allergic reaction is uniform regardless of age, trigger or clinical stage. According to the recommendation of the WAO, many international and national guidelines, epinephrine is considered the drug of choice for anaphylaxis and any general allergic reaction [7,8]. Epinephrine is the only drug that reduces both hospitalization and mortality rates in patients with anaphylaxis. Based on expert opinion, there is no absolute contraindication for the use of epinephrine in severe allergic reaction.

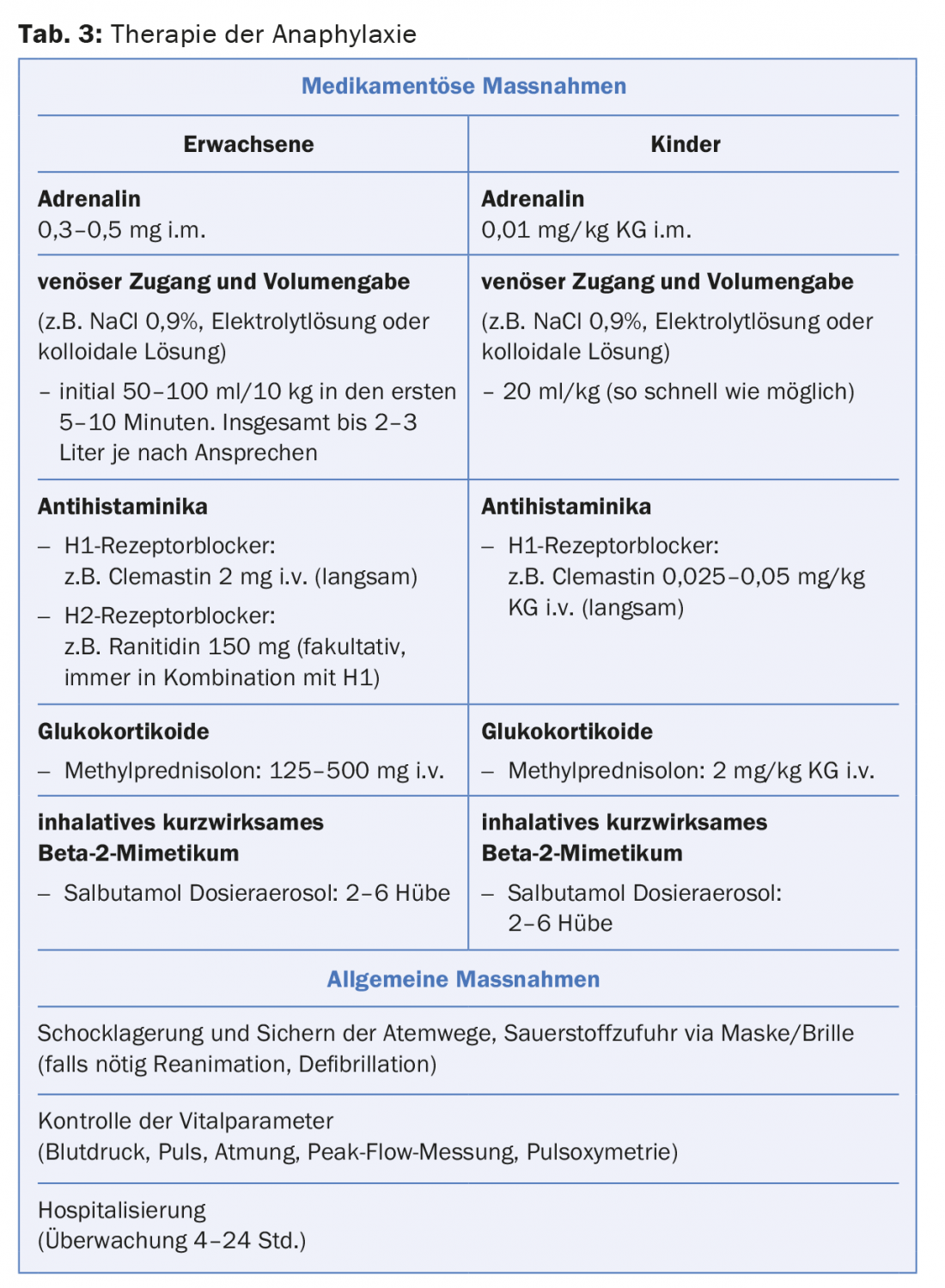

Adrenalin should always be administered intramuscularly and not subcutaneously! Thanks to intramuscular absorption, sufficient plasma levels are achieved in a much shorter time than with subcutaneous administration. The most ideal site for intramuscular administration of epinephrine is the anterolateral area of the thigh. In adults, the initial dose should be at least 0.3-0.5 mg (rule of thumb 0.1 mg per 10 kg body weight). If no therapeutic effect is apparent after three to five minutes, the administration of adrenaline should be repeated. The anaphylaxis-inducing or suspected source should be eliminated as soon as possible (e.g., stop the infusion) – if present, oxygen should be given (mask 40-60%, goggles 8-10 l/min). Because fluid loss to tissues can be as high as 35% within ten minutes, venous access should be established and volume added as soon as possible after administration of epinephrine (50-100 ml/10 kg in the first five to ten minutes). It does not matter whether colloids or electrolyte solutions are used (tab. 3). If the circulation is not sufficiently stabilized, administer epinephrine intravenously or at the perfusor (0.1-0.4 µg/min). For intravenous administration, epinephrine should be diluted at least 1:9 with NaCl 0.9% or better 1:100 (e.g., 1 mg epinephrine in 99 ml NaCl 0.9% corresponds to 10 µg/ml) and injected slowly – if possible under ECG monitoring.

A retrospective observational study analyzing the safety of epinephrine in the treatment of anaphylaxis found that only 1% of those treated intramuscularly – compared with 10% who received epinephrine intravenously – developed adverse reactions to epinephrine administration. No epinephrine overdose was observed with intramuscular injection [9].

After creating an infusion, an i.v. antihistamine (clemastine, dimetindene) should be administered (Tab. 3). Clemastine in particular should be injected slowly, over two to three minutes and not as a bolus, as a drop in blood pressure can be induced. Depending on the situation, e.g., sole urticaria or mild facial swelling, an antihistamine may be given orally. It should be noted that a therapeutic effect after oral administration can be expected after more than half an hour at the earliest. Corticosteroids are not primary emergency medications for anaphylaxis. Even administered intravenously, they develop a certain efficacy after one hour at the earliest. However, corticosteroids should not be withheld in patients with asthma, pulmonary disease, and those who develop angioedema.

Clarification and aftercare

Every patient should be referred for allergic evaluation after a general allergic reaction, but especially after anaphylaxis. According to our vast experience (several publications), the majority of reaction triggers (>90%) can be identified with sufficient accuracy. Those affected can be made aware of the sources of danger and instructed on essential behavioral measures. The risk of a next and usually unforeseen allergic general reaction can thus be reduced (odds ratio 0.78) [10]. In some cases, such as hymenopteran venom allergy, a high degree of long-term protection against re-exposure can be achieved with specific immunotherapy [11].

The optimal time for an allergological workup after a severe allergic reaction is not clearly defined. In the case of insect venom allergies, clarification is usually recommended at the earliest three to four weeks after an acute event, and in the case of drug allergies, preferably within six months.

It has become established in many places that an emergency medication kit is given to the patient after an allergic reaction. This set is composed of an antihistamine (e.g., two tablets of levocetirizine or fexofenadine) combined with a corticosteroid preparation (e.g., prednisolone two tbl 50 mg). Instead of tablets, antihistamines may be prescribed as drops (e.g., cetirizine drops 0.25 mg/kg) or syrup (e.g., desloratadine 1.25-2.5 mg) and water-soluble tablets (e.g., betnesol 0.2-0.5 mg/kg) in young children. This combination may be sufficient for cutaneous allergic reactions, but taken orally cannot suppress severe systemic reactions such as hypotension, shock, or even acute bronchospasm. Therefore, an epinephrine auto-injector should always be prescribed for anaphylactic reactions. These epinephrine injectors are prescribed far too infrequently around the world despite a given indication. However, the regulation alone is not enough. Each patient should be instructed on the proper use of the particular epinephrine injector. Observational studies from the United States have shown that of 261 patients with established anaphylaxis, only 11% used epinephrine auto-injector on re-exposure. This was because 52% of them had not received an epinephrine auto-injector, and only 16% could use it properly [12]. Structured educational programs to improve anaphylaxis management and availability of epinephrine auto-injectors are needed. In Switzerland, anaphylaxis training courses for affected persons, parents, teachers or other professions are offered by the aha! Allergy Center Switzerland, Bern, offered.

Literature:

- Alvarez-Perea A, et al: Anaphylaxis in Adolescent/Adult Patients Treated in the Emergency Department: Differences Between Initial Impressions and the Definitive Diagnosis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2015; 25(4): 288-294.

- Wang J, Young MC, Nowak-Węgrzyn A: International survey of knowledge of food-induced anaphylaxis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014; 25(7): 644-650.

- Tejedor-Alonso MA, Moro-Moro M, Múgica-García MV: Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis: Contributions From the Last 10 Years. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2015; 25(3): 163-175.

- Simons FER, et al: 2015 update of the evidence base: World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines. World Allergy Organ J 2015; 8(1): 32.

- Valent P: Risk factors and management of severe life-threatening anaphylaxis in patients with clonal mast cell disorders. Clin Exp Allergy 2014; 44(7): 914-920.

- Ansley L, et al: Pathophysiological mechanisms of exercise-induced anaphylaxis: an EAACI position statement. Allergy 2015; 70(10): 1212-1221.

- Lieberman P, et al: Anaphylaxis-a practice parameter update 2015. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015; 115(5): 341-384.

- Helbling A, et al: Emergency treatment in allergic shock. Swiss Med Forum 2011; 11(12): 206-212.

- Campbell RL, et al: Epinephrine in anaphylaxis: higher risk of cardiovascular complications and overdose after administration of intravenous bolus epinephrine compared with intramuscular epinephrine. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3(1): 76-80.

- Clark S, et al: Risk factors for severe anaphylaxis in patients receiving anaphylaxis treatment in US emergency departments and hospitals. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014 Nov; 134(5): 1125-1130.

- Koschel DS, et al: Tolerated sting challenge in patients on Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy improves health-related quality of life. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2014; 24(4): 226-230.

- Altman AM, et al: Anaphylaxis in America: A national physician survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135(3): 830-833.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(1): 16-20