Fall prevention measures can reduce the rate of falls by up to 50%. Family physicians are suited to play a key role in the primary and secondary prevention of falls and their consequences. Risk factor screening and simple, clinically feasible assessments help identify those at risk for falls and are important for monitoring outcomes and motivating patients. We recommend that primary care physicians learn about fall prevention services in their region and coordinate measures for patients at risk of falling. Interdisciplinary collaboration, including with physical therapists, is important.

Falls in old age are frequent and often serious for those affected. In particular, they can be associated with loss of mobility, decrease in independence, anxiety and depression, resulting in a tremendous loss of quality of life. As a consequence of the demographic development in Switzerland, the general practitioner is also increasingly confronted with the problems related to age and falls in his practice. According to the latest figures from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, the number of people over 65 in the population will increase by around 80% across Switzerland by 2045. Around one in three people in this age group falls at least once a year; according to the BFU, this currently affects around 80,000 people in Switzerland. In 2045, about 140,000 falls per year must already be expected. In about 20-30%, injuries requiring treatment are the result, and 5-15% suffer a fracture [1]. Falls are not only a major threat to the health and quality of life of those affected, but also represent an increasingly large socioeconomic burden for our healthcare system. Preventive measures to avoid falls and fractures are therefore urgently needed and are demanded and promoted from various sides.

A report within the framework of “Health Promotion in Old Age” shows that an interdisciplinary collaboration of professionals is needed for the implementation of evidence-based fall prevention measures in Switzerland. In particular, it is emphasized that family physicians have a leading role to play in this regard. Patients make better use of prevention recommendations when their primary care physician is involved in the planning process [2]. We are also of the opinion that the general practitioner is predestined to have a preventive effect on falls, in particular due to a relationship of trust with the patient, which usually goes back many years, as well as comprehensive knowledge of the patient’s medical history. If there is a suspicion of an increased risk of falling, it gives him the opportunity to address the problem, conduct a fall risk screening and initiate appropriate preventive measures.

Since a fall risk is usually multifactorial, we recommend a risk factor survey (medical history and physical status) combined with the performance of simple fall assessments for fall risk screening in the family practice.

Fall risk factors

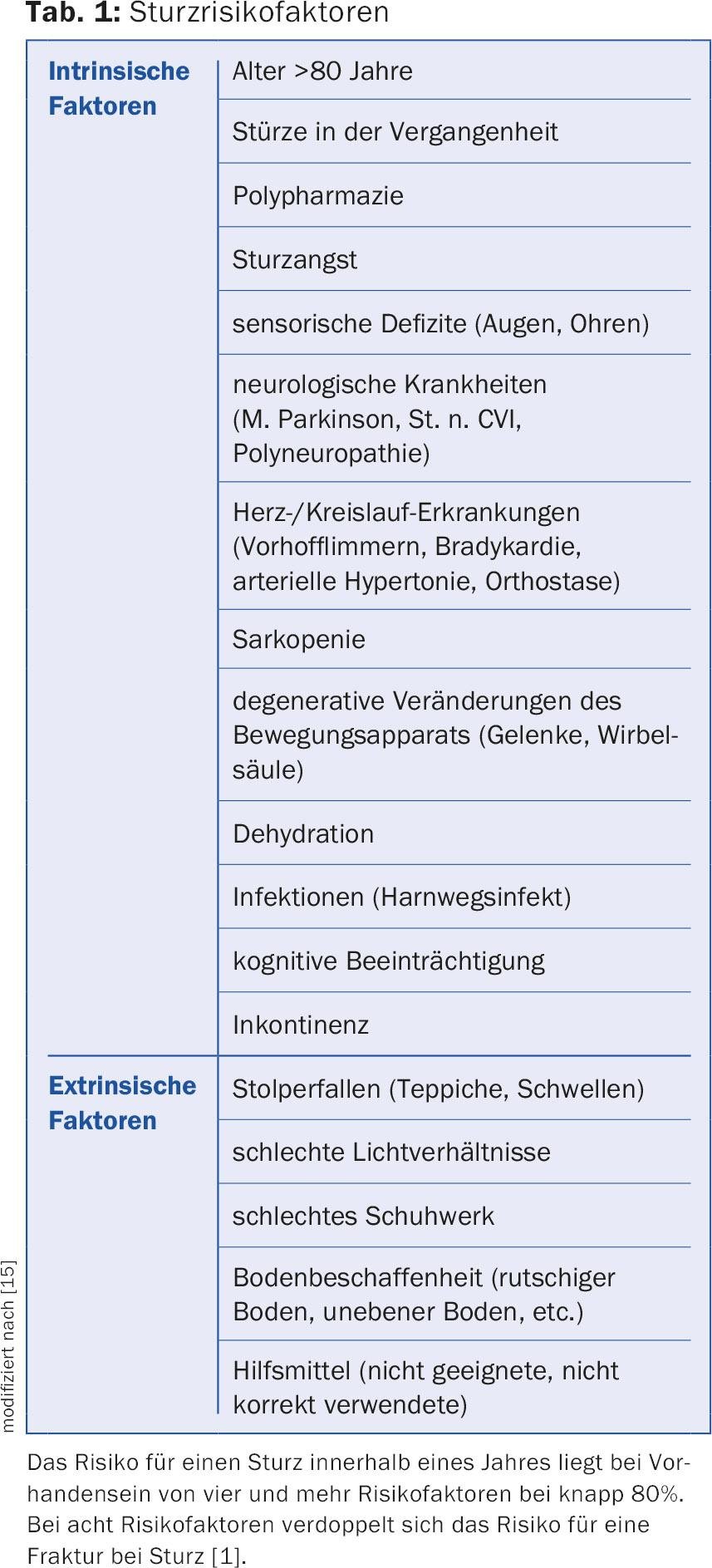

Fall risk factors can be divided into three main groups:

- Intrinsic factors related to changes in the aging body (physiological or disease-related).

- Extrinsic factors, which include external conditions such as housing and living environment.

- Behavioral factors, corresponding to high-risk behavior that is not appropriate to physical abilities and resources.

Table 1 shows an overview of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors.

General anamnesis

A focused history can provide important information to assess current fall risk. This should include questions about whether there has been any recent change in walking, perceived balance problems, dizziness, or a decrease in muscle strength, whether falls have occurred since the last visit to the office, or whether there is a fear of falling. Fear of falling is a factor that should not be underestimated, which can lead to an unfavorable control loop of fear-avoidance behavior and loss of mobility (Fig. 1).

Increasing unsteadiness when walking may also be the first sign of the onset of cognitive impairment. Executive function – the ability to plan procedures – is one of the first functions that can be affected when cognition is impaired. Patients have difficulty performing multiple procedures simultaneously (e.g., walking and talking at the same time). There is a limitation of “dual tasking” which is associated with an increased risk of falls [3,4].

Furthermore, it must be asked whether there are complaints related to the musculoskeletal system, whether symptoms of a cardiovascular or neurological disease have occurred, and also whether problems with memory have been detected. Last but not least, urge incontinence should be specifically asked about. Rushing to the toilet may be associated with an increased risk of falling, both directly as a result of reduced walking ability and as a consequence of reduced executive function. The patient must concentrate on holding urine and no longer has the resources to pay attention to the gait at the same time.

If a fall has already occurred, the more specific circumstances must be inquired about: Was there dizziness or loss of consciousness? Was it a trip and fall? At what time of day or night did the fall occur? Was a sleep medication taken before the event? Did the fall occur before or after going to the bathroom? Was the patient able to get up on his or her own, or did prolonged recumbency occur?

Medication history

Regular medication review is very important in fall prevention. In particular, centrally acting drugs such as neuroleptics, antidepressants or hypnotics have an increased risk of falls. Benzodiazepines should generally be avoided, as they are a frequent cause of falls at night, especially if incontinence is still present and patients have to get up during the night because of it.

Physical status

Physical status includes examination of the cardiovascular system, and blood pressure should be measured in both sitting and standing positions to rule out orthostatic hypotension, which is often responsible for a fall. Furthermore, it should be checked whether a cardiac arrhythmia is present and whether the blood pressure is well adjusted. The status also includes a neurologic examination, particularly with the question of whether polyneuropathy is present, and an assessment of the musculoskeletal system.

It is mandatory that the sensory organs eyes and ears should also be assessed in any fall risk assessment status [1].

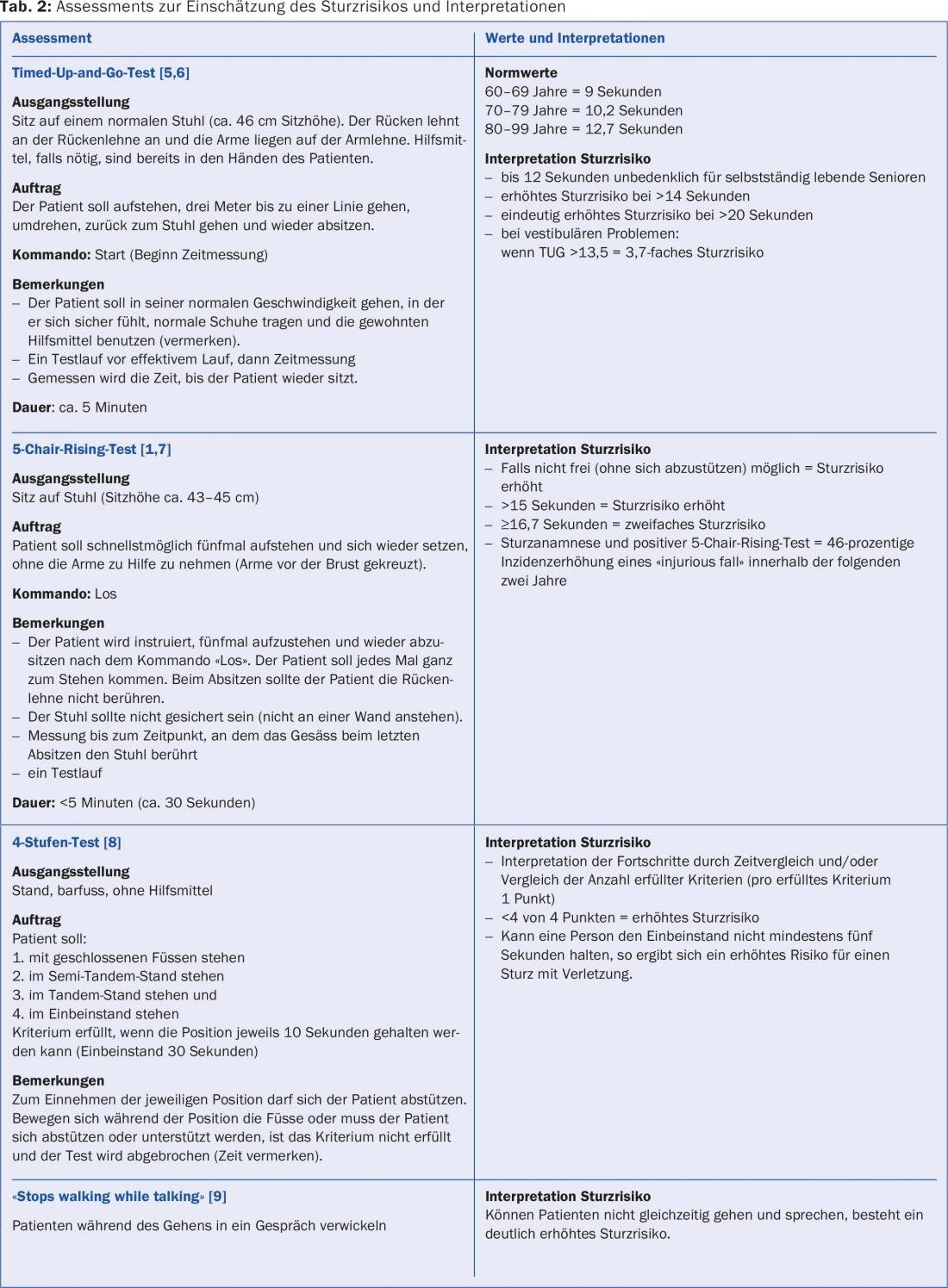

We consider the performance of targeted fall assessments to be very important both for the planning of interventions and for the evaluation of the success of therapy. Table 2 provides an overview of simple functional assessments that can be easily implemented in the family practice, which are primarily based on the assessment of muscle strength, balance and walking ability and which have predictive value for falls.

Interventions

The aim of the measures to be introduced is to modify or reduce the intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors, but also to carry out behavioral prevention.

A number of evidence-based, multi- and monofactorial, fall prevention interventions exist that focus on intrinsic and extrinsic risk factor reduction and behavioral prevention.

Regarding multifactorial programs, fall rates have been reported to be reduced by 25-46%, but even simple exercise programs based on balance and/or strength exercises can reduce the risk of falls by 10-50% in all older people [1,10].

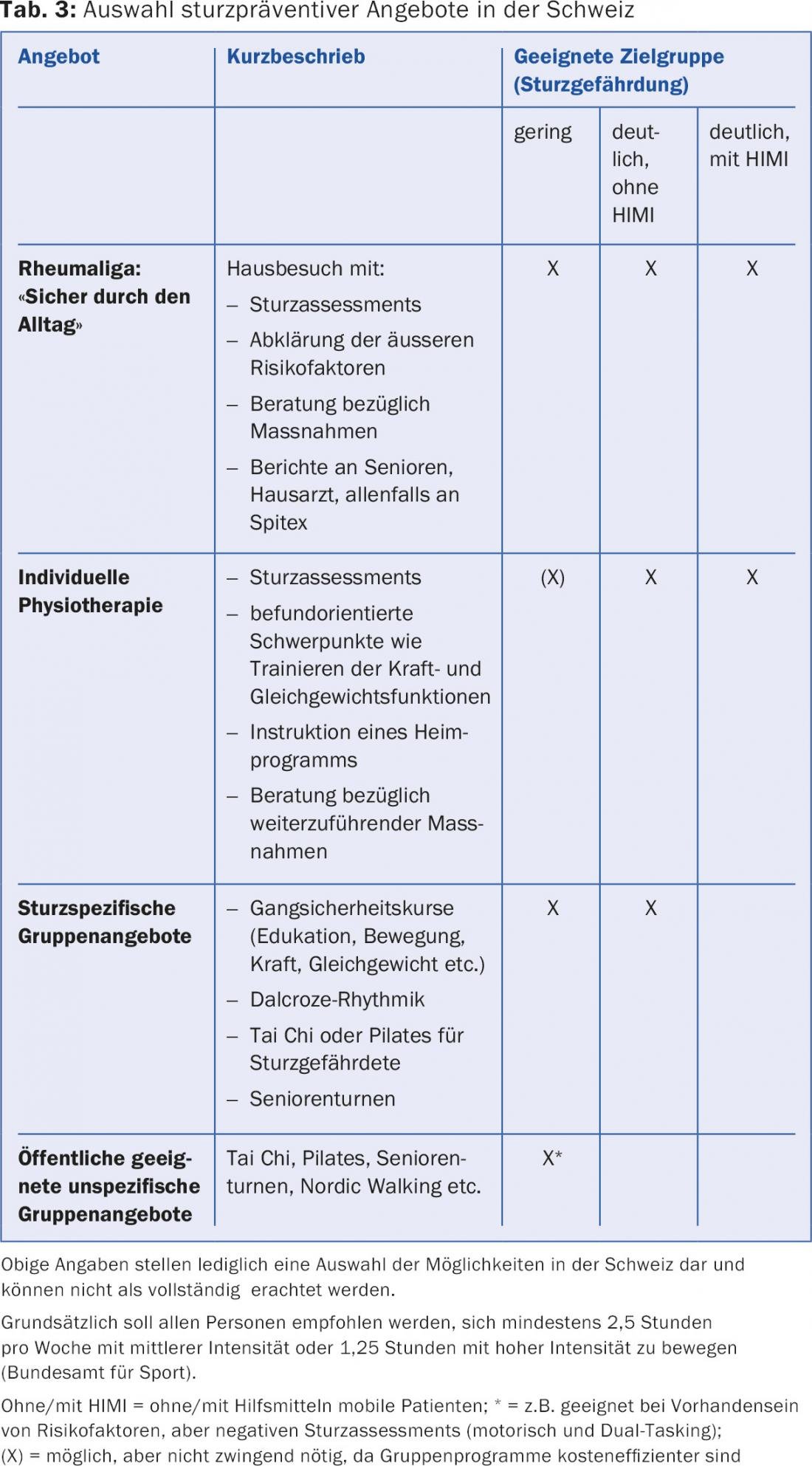

Which measures are suitable for a patient must be assessed on an individual basis. Some intervention approaches by the primary care physician have already been mentioned above. Because of the multifactorial causes of falls described above, the general practitioner should coordinate further measures if indicated ( Table 3).

Regarding secondary prevention of falls after initial fracture has already occurred, studies in patients after hip fracture, for example, indicate that longer, more intensive rehabilitation is necessary to achieve significant improvements in functional abilities [11–13]. Repeated fall risk screenings are especially important for these patients, as we have observed that even patients who are subjectively already satisfied and well mobile often remain at risk for falls. It is therefore important not to stop rehabilitation too early, but to carry it out with sufficient intensity and for a long time in order to sustainably maintain mobility and independence in a fall-preventive manner.

Since fractures in old age are often associated with osteoporosis and the individual risk of fracture increases significantly with decreasing bone density after an already sustained fracture, osteoporosis screening and adequate therapies in case of pathological findings are also mandatory in patients who have sustained a fracture due to a minor trauma and should be part of standard care [14].

Important links:

www.bfu.ch/de/fuer-fachpersonen/sturzprävention

www.rheumaliga.ch/Sturzpraevention

www.prosenectute.ch

Literature:

- Jansenberger H: Fall prevention in therapy and training. Thieme Verlag 2011.

- Gschwind YJ, et al: Fall prevention. Basel University Hospital. Acute Geriatrics 2011.

- Verghese J, et al: Validity of divided attention tasks in predicting falls in older individuals: a preliminary study. JAGS 2002; 50: 1572-1576.

- Mirelmann A, Hermann T, Brozgol M: Executive function and falls in older adults: new findings from a five-year prospective study link fall risk to cognition. PLoS One 2012; 7(6): e40297.

- Podsiadlo D, et al: The timed “up & go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. JAGS 1991; 39: 142-148.

- Oesch P, et al: Assessments in Rehabilitation. Volume 2: Musculoskeletal system. Verlag Hans Huber 2011.

- Ward RE, et al: Functional performance as a predictor of injurious falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(2): 315-320.

- Gardner M, et al: Practical implementation of an exercise-based falls prevention program. Age and Ageing 2001; 30: 77-83.

- Lundin-Olsson L, et al: “Stops walking while talking” as a predictor of falls in elderly people. Lancet 1997; 349(9052): 617.

- Gillespie LD, et al: Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Sep 12; 9: CD007146.

- Sylliaas H, et al: Prolonged strength training in older patients after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Age and Ageing 2012; 41: 206-212.

- Auais MA, et al: Extended exercise rehabilitation after hip fracture improves patients’ physical function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther 2012; 92: 1437-1451.

- Handoll HH, et al: Interventions for improving mobility after hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011 Mar 16; (3): CD001704.

- Marshall D, et al: Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 1996 May 18; 312(7041): 1254-1259.

- Zeyfang A, et al: Basiswissen Medizin des Alterns und des alten Menschen. Springer-Verlag 2013.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(12): 10-14