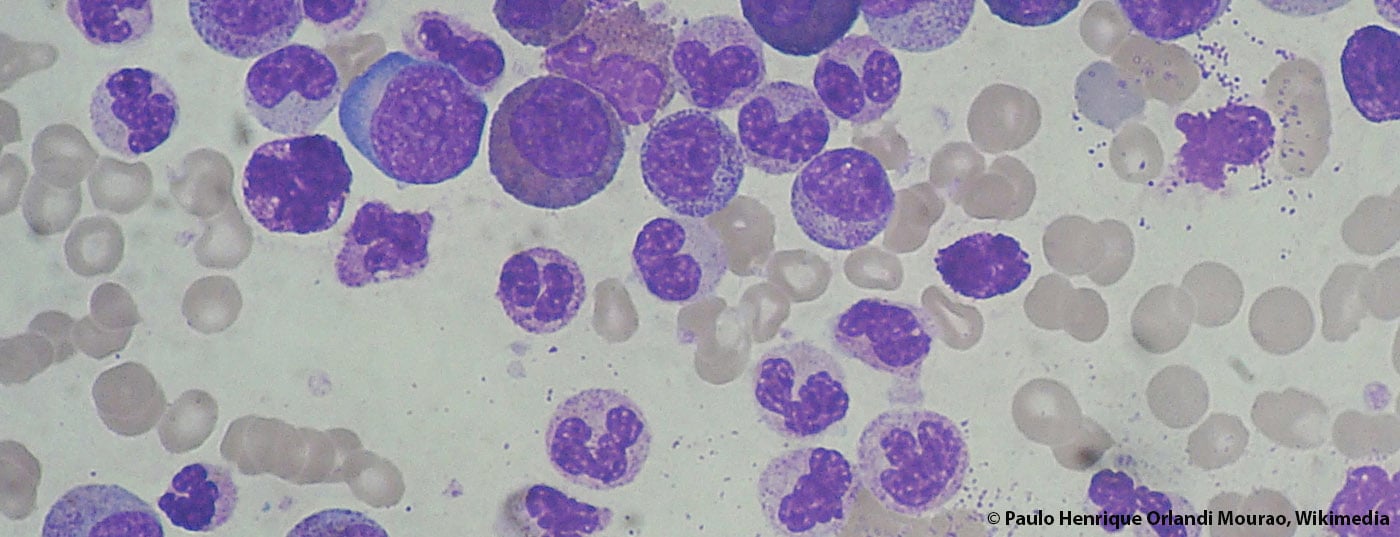

A lot has happened in the field of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in recent years. Response and survival rates have risen sharply, and some patients are even said to be cured. A just-published Annals of Hematology supplement on CML provides a broad overview of the state of diagnostics and therapy in 2015.

According to various European registries, the incidence of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has been stable in recent years. The annual rate is 0.7-1.0/100,000. On average, the age at initial diagnosis is 57-60 years. Exact prevalence data are not known – numbers around 10-12/100,000 population are assumed, with a steady increase here due to greatly improved survival rates. This poses major challenges for healthcare systems; after all, the cost of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy is high. In this respect, it is interesting to see how the generics market will develop. The patent for imatinib expires next year.

Treatment has greatly improved

The therapeutic field in CML is evolving rapidly. Survival rates have risen sharply in recent years and the goal of treatment is increasingly shifting from palliation to cure. Patients who respond to TKIs now have almost as good an overall survival as the healthy population. In some cases, the response is so pronounced that the therapy can possibly even be terminated. This makes it even more important to develop concepts and studies for treatment-free remission.

What choice do you have today in the first, second and third lines?

It is undisputed that imatinib has revolutionized the treatment of CML. However, whether the usual dose of 400 mg is appropriate for all patients to achieve optimal outcome is currently under debate. Several studies therefore investigated the potential benefit of modified imatinib treatment or the use of a second-generation TKI in the first-line setting. Some approaches with high-dose (800 mg) or dose-adapted imatinib therapy or also the combination with interferon, which can still be described as experimental, showed a better cytogenetic and molecular response than with the standard variant – however, so far without benefit in progression-free (PFS) or overall survival (OS). In addition, dasatinib and nilotinib were approved in the first-line setting, expanding options in the treatment of newly diagnosed CML. These two agents induce a very rapid and sustained molecular response.

The second-generation TKIs dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib are also highly likely to be effective in the second line. Their overall efficacy is comparable, so physicians should primarily consider the BCR-ABL1 mutation profile and disease history when making treatment decisions: If there is no mutation or a mutation that responds well to these agents, decisions should be made based on the disease history. On the other hand, if one of the few BCR-ABL1 mutations is present that does not respond well to any of the agents, the TKI that has shown clinical activity against the specific mutation should be selected. In patients with T315I mutations or after failure of nilotinib or dasatinib, the third-generation TKI ponatinib is an option, although its optimal dosing is still under investigation.

Overall, it has been shown that assessment of molecular and cytogenetic response allows prognostic risk stratification of patients as early as three months on treatment. Thus, early response to TKIs is critically related to long-term outcome. This has been demonstrated for both imatinib and second-generation TKIs and likewise for second-line treatment in multiple studies. If a patient on a particular TKI shows early treatment failure, an unfavorable outcome can be assumed, which in turn makes a timely change in treatment all the more important.

Consider all treatment options

In any case, the advantages and disadvantages of long-term TKI therapy should be compared with those of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Indeed, although this remains an option as second- and third-line therapy in first chronic phase CML, transplantation rates have declined significantly since the introduction of TKIs (rates have declined less for the indication as salvage therapy in advanced disease).

Some authors in this issue of Annals of Hematology are critical of the primary consideration of disease risk (defined as failure of TKI therapy) in the decision whether to transplant: they suggest a more balanced approach that includes transplant risk and economic aspects in addition to disease risk. HSCT should be integrated into the treatment algorithm from the time of initial diagnosis. Early after the first treatment failure with TKI, HSCT should be evaluated if the affected patients have a high risk of disease but a low risk of transplantation. Conversely, in patients with very advanced disease and high risk for transplantation, HSCT should be used restrictively and possibly only in the trial setting.

Side effects under TKI

On the one hand, most patients benefit significantly from TKIs, but on the other hand, side effects have come into sharper focus precisely because of the long-term survival now achieved. Anyone who has to be treated with such agents for a lifetime is interested not only in effectiveness but also in tolerance.

Overall, TKIs have a relatively good safety profile in clinical practice because, although many mild to moderate side effects occur, these are usually limited to the beginning of therapy and are well controlled or even resolve spontaneously thereafter. At present, however, questions remain about long-term safety – especially with regard to the newer TKI generations. For example, these new agents have recently been shown to exert adverse and irreversible effects on organs such as the heart and lungs in some cases, particularly in the presence of comorbidities. Thus, selecting the right TKI requires close scrutiny of disease, patient, and drug parameters.

Source: Annals of Hematology 2015; 94(2).

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(5): 22-24.