Women with known immunosuppression should receive annual cervical screening. When cervical screening is performed, the perianal, vulvar, and vaginal areas should also be inspected. The use of a screening procedure also requires an indication. Unnecessary examinations often result in a clinically irrelevant result, which leads to further diagnostics and unnecessary psychological stress for the patient. Many questions and uncertainties arise in connection with HPV and dysplasia. Take the patient and her psychological stress seriously. HPV vaccination should be strongly recommended for all women under 26 years of age.

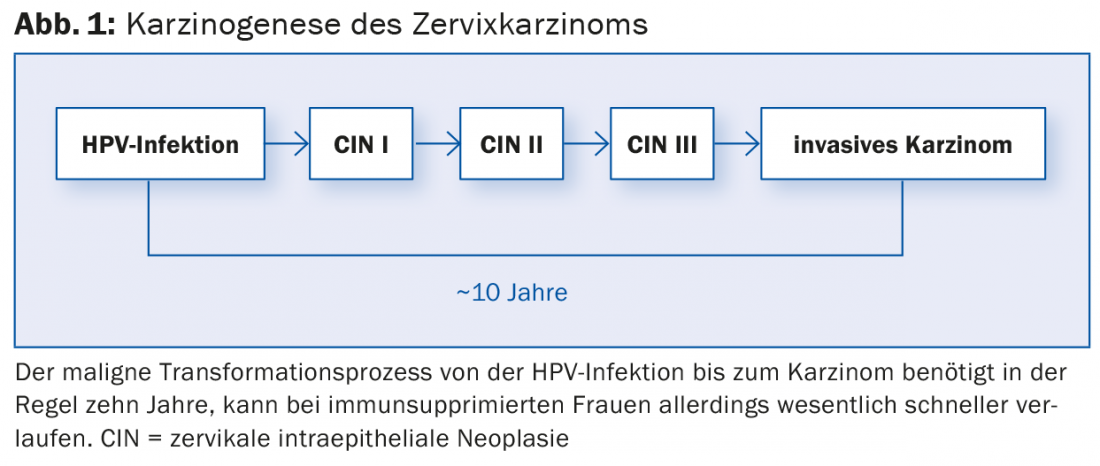

The introduction of the first “vaccination against cancer” has generated a great deal of public interest in the topic of “cervical cancer”. Nevertheless, a large part of the population is unaware of the causative human papilloma virus (HPV). This is surprising, since over 80% of all sexually active women become infected with an HP virus during their lifetime. This makes HP virus infection the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide. Certain HPV types, referred to as high-risk types (hr HPV), are the obligatory prerequisite for the development of cervical carcinoma [1]. However, more than 90% of infections with hr HPV types are asymptomatic without being noticed and leave no harm. However, in a very small proportion of women, infection may initialize a malignant process in which precancerous lesions of varying severity develop stage by stage (Fig. 1) . In the absence of therapy, this may ultimately result in cervical carcinoma.

Screening

The long time interval of about ten years in immunocompetent women between hr HPV infection and appearance of cervical carcinoma allows early detection and therapy of premalignant lesions.

The HP virus exhibits strict tissue tropism. It affects certain cells of the so-called transformation zone of the cervix. Screening is therefore performed by means of a cytological cell smear of the endo- and ectocervix. The false-negative rate of this method is unfortunately high (50%), especially in glandular lesions. In this regard, the conventional Papanicolaou test and thin-layer cytology perform equally well and poorly, respectively. To increase the relatively low sensitivity, cytology must be repeated regularly. The time interval between examinations in the case of an inconspicuous result is currently under discussion. Current recommendations are for checks every two years between the ages of 21-29 years and every three years between 30-70 years [2].

In Switzerland, cytological cell changes are usually designated according to the Bethesda system. Here, the severity of premalignant precursors is divided into low-grade intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) and high-grade intraepithelial lesions (HSIL). Some laboratories also use the Munich nomenclature commonly used in Germany.

Due to the high false-negative rate, alternatives to current screening methods are being sought. One option currently under discussion is the cervical HPV test, which will also become established in Switzerland in the next few years, at least as an additional method [3].

The opportunistic screening program for the early detection of cervical cancer in Switzerland is based on a worldwide observation: cervical cancer is associated with poverty, poor access to the health care system, but also living in rural areas and low education. These socioeconomic and geographic factors also play a role in Switzerland. Rural cantons have higher rates of cervical cancer than urban ones; women from socially disadvantaged backgrounds have higher rates of cervical cancer, diagnosis occurs at later stages, and survival is lower.

In addition to cervical carcinoma, hr HP viruses can also cause vulvar, anal, and laryngeal carcinomas. No screening procedure has yet been established for these diseases.

What to do in case of abnormal cytological cervical smears?

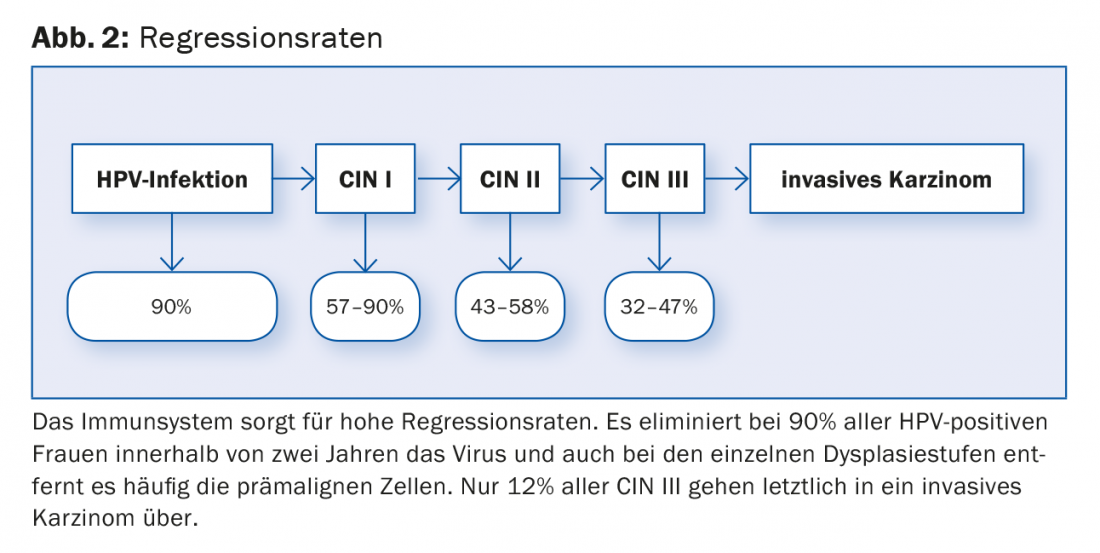

hr HPV infection is a very common event and very rarely leads to malignancy regardless of screening. The probability of spontaneous regression of each precursor is very high (Fig. 2) . The clinician’s dilemma is that to date we have no way of predicting in whom and why the infection will ultimately lead to cervical cancer.

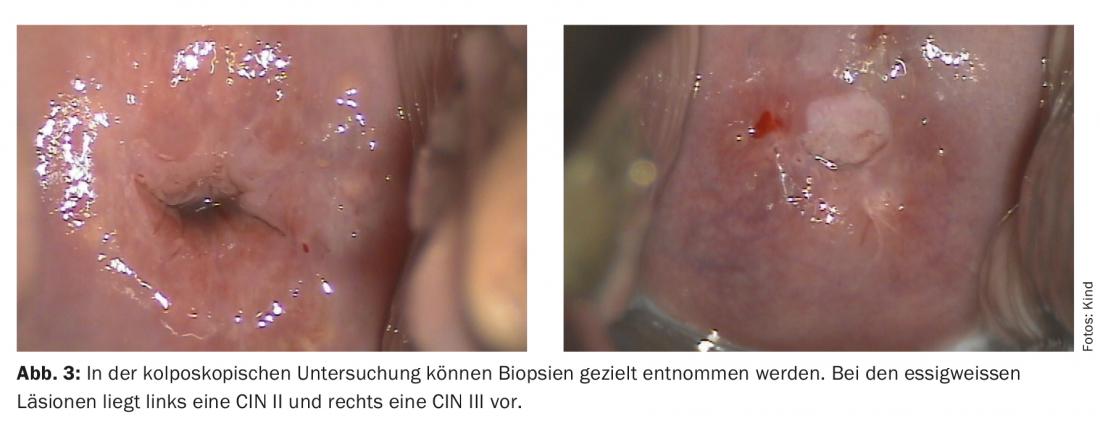

In Switzerland, there are as yet no detailed algorithms for proceeding with cell changes, as is the case in the USA, for example [4]. For this reason, we have developed algorithms together with the Cantonal Hospital Baselland, which can be viewed online free of charge [5]. Listed here is how to proceed with which cytological and histological result. In many cases of cytological cervical carcinoma precursors, further examination in terms of colposcopy must be performed. The cervix is examined by means of transvaginal magnification and cell changes are described macroscopically. If necessary, a histological specimen is taken from the appropriate sites. Special dysplasia consultation hours are available for this clarification diagnosis. These should be quality controlled to avoid over- and under-therapy.

While screening is based on cervical cytology, definitive diagnosis of higher grade dysplasia is made histologically. Three degrees of severity are distinguished: mild cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN I), moderate-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN II) and severe cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN III) (Fig. 3).

The approach to the various alterations has become more complex in recent years, affecting CIN II lesions, for example. In the past, it was recommended to treat all patients with CIN II. Today, this is considered absolutely indicated only in patients with CIN III. In patients with CIN II and not completed family planning, experienced colposcopists may also perform follow-up every six months. Due to the high spontaneous regression rate of CIN II lesions, especially in young women, this usually eliminates the need for surgical therapy. The regression rate for CIN III is also high, but there is currently no test that shows us which patient will develop a malignancy. For this reason, all patients with CIN III have been treated up to now.

Therapy of choice for women with CIN III and CIN II with completed family planning is conization. This is a routine procedure that can be performed on an outpatient basis and takes well under 30 minutes. During conization, cone-shaped excision (diathermic snare or laser) is used to treat high-grade dysplasia in an organ-preserving manner.

The most common complication is postoperative bleeding. The most feared complication is the increase in the risk of preterm birth in the next pregnancy [6]. This depends on the size of the cone and is the reason why today no conizations should be performed without a really clear indication.

Six months after conization, an HPV test is performed. If this is negative and a new HPV test after another six months is also negative, the patient is considered “cured”. Today, however, it is believed that the HPV virus is not completely eliminated from the body in all patients, but persists in some and just cannot be detected with an HPV test. Previous studies show that reactivation of these persistent infections can occur even after more than 30 years. For this reason, women who report a history of CIN II or higher grade lesions are recommended cervical screening once a year for life.

The “vaccination against cancer

In 2007, the two HPV vaccines Gardasil® and Cervarix® were approved in Switzerland. Both vaccines are effective against the most common hr HPV types 16 and 18, Gardasil® also against HPV types 6 and 11, which are responsible for the development of genital warts. The active principle of the vaccines is the endogenous development of antibodies by VLPs (“virus like particles”), biotechnologically produced viral envelopes without effective nucleic acid-containing content. Thus, there is no infectivity.

The Federal Commission on Immunization (EKIF) recommends vaccination for all girls 11 to 14 years old – as well as a booster shot for 15- to 19-year-old girls. Vaccination is also useful for women up to 26 years of age and is paid for as part of cantonal vaccination programs [7]. Beginning in the fall of 2015, male adolescents will also be included in the vaccination recommendation. HPV vaccination shows up to 100 percent effectiveness on new infections and precancerous lesions in the anogenital region associated with the HPV types included in each vaccine. Due to the high proportion of HPV 16/18-induced cervical cancers, HPV vaccination is expected to prevent approximately 70% of all cervical cancers. Because current vaccines do not include all hr HPV types, vaccinated women should continue to participate in screening. Unfortunately, the great interest in “vaccination against cancer” is not reflected in vaccination rates.

Despite the fact that more than 180 million doses of vaccine have now been administered worldwide, the debate about the safety of vaccination has not yet died down. However, its safety has been clearly confirmed in numerous studies and recommendations by national and international bodies.

In 2012, the vaccination rate in Switzerland averaged 55% with large regional differences. Unfortunately, vaccination rates are often lowest in the very cantons that also have the highest cervical cancer rates, i.e., those that have not yet adequately participated in cancer screening.

In comparison, 80% of all women in Australia were vaccinated in 2012, and significant reductions in rates of pre-cervical cancer and genital warts are already evident [8].

Every year, approximately 240 women in Switzerland develop cervical cancer and 80-90 women die from it. Thousands of women regularly have to go for medical check-ups because of abnormal smear results, many of them to dysplasia consultations for biopsy collection and ultimately for conization. One aspect of HPV infection and precancerous cervical lesions that has received too little investigation and attention to date is the significant psychological impact on affected women, with reduction in quality of life and impact on relationship and sexual life. With a high vaccination rate, a majority of these would be preventable.

It is the responsibility of all stakeholders in the health care system to continue to improve primary and secondary prevention.

Literature:

- Muñoz N: Human papilloma virus and cancer: the epidemiological evidence. J Clin Virol 2000; 19(1-2): 1-5.

- Gerber S, et al: Update of screening for cervical cancer and follow-up by colposcopy. www.sggg.ch; 2012 Expert Letter No. 40.

- Ronco G, et al: Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. The Lancet 2014; 383(9916): 524-532.

- Saslow D, et al: American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology Screening Guidelines for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2012; 62(3): 147-172.

- www.unispital-basel.ch (gynecological clinic, information for referring physicians)

- Arbyn M, et al: Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008; 337: a1284.

- www.ekif.ch: Swiss Vaccination Plan

- Ali H, et al: Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346: f2032.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(4): 22-24