Now they fly again, the bees and the wasps. While bees are bred and sheltered, wasps generally have a bad reputation. However, most insects from the order Hymenoptera (Hymenoptera) only sting when they themselves are threatened, or when they are protecting their nests. Our specialists from Bern show how the allergy cascade works and how to act in an emergency.

Most stings are painful and usually only cause local swelling, but no one likes to be stung. There are probably few people who have never been stung by a Hymenoptera in their lifetime. Children are stung more often than adults and men more than women, which can probably be explained by lifestyle and activity. The frequency of general allergic reactions after a bee or wasp sting is estimated to be between 3 and 4% in Switzerland [1–3]. The risk of allergy increases with the frequency of stings, which is why people who are occupationally exposed to an increased risk of stings (e.g. beekeepers, landscapers, farmers) are significantly more at risk than the average person in the normal population. The risk increases especially when two stings from the same insect family (e.g., wasps) occur within a short period of time (2-6 weeks) [4].

Classification of the Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera venom allergy is one of the most important causes of allergic and anaphylactic reactions worldwide, which can also be fatal at some point. In Switzerland, two to four people die each year after a bee or wasp sting, in Europe about 200, and in the USA 100 [3, 5]. Frequently, deaths involve adults over 40 years of age with preexisting cardiovascular or chronic lung disease or patients with previously undiagnosed mastocytosis [2–4].

The Hymenoptera include the wrinkled wasps with the subfamilies of true wasps (Vespinae) and field wasps (Polistes spp.), bees (Apidae), and ants (Formicidae, Myrmicinae). The true wasps include the short-headed wasp (Vespula spp.), the longheaded wasp (Dolichovespula spp.), and the hornet (Vespa spp.) [2, 3]. In our latitudes, it is mainly the short-headed wasp that is responsible for most allergic events, as it often joins humans and may well spontaneously sting once in a while. Stings by hornets or longheaded wasps, on the other hand, are rather rare and occur practically only near their nests. The elegant field wasps are found practically everywhere in Europe except in Great Britain, but mainly in the Mediterranean region.

The ants sting too! While our native species have only a rudimentary stinging apparatus, ant bites are not uncommon causes of severe general allergic reactions, especially in the southern states of the USA, South and Central America, and Australia [2, 3, 6].

Poison and allergens

On average, about 50 µg of venom enters the skin after a bee sting, but significantly less after a wasp sting [3, 7, 8]. Nevertheless, the amount is sufficient for allergic shock. The venom of bees and wasps is composed of various components and contains biogenic amines such as histamine, peptides such as mellitin, and insect-specific allergens. The major allergens in bee venom are phospholipase A2 (Api m1), hyaluronidase (Api m2), and acid phosphatase (Api m3) [2, 3, 9-11]. In wasp venom, it is phospholipase A1 (Ves v1) and antigen-5 (Ves v5). To date, twelve different bee and six wasp venom allergens have been identified [3, 9-11]. While the venom composition of bee and wasp venom is different, wasp venom allergens including those of hornets are very similar [9]. However, there are differences between the venom of the field wasp and the other wasps native to our country, which must be taken into account if immunotherapy is indicated.

Types of sting reaction

The sting reaction following a hymenopteran sting can be classified as local, severe local, systemic allergic, systemic toxic, and unusual [2–4]. A normal reaction corresponds to a swelling of 5-10 cm in diameter, which usually subsides within a few hours, although itching may persist for days. Severe local reactions are characterized by swelling >10 cm in diameter and lasting more than one day. These reactions can remain clearly visible for up to a week. General reactions after insect stings are mostly IgE-mediated. Based on severity, they are classified either according to H. L. Mueller (most commonly used in Switzerland, Table 1) or Ring & Messmer [2, 3, 7, 22]. Multiple stings – from 10-50 in children and usually from 100 in adults – can result in toxic reactions, and these are usually due to a cytotoxic effect of mellitin and kinin, which can lead to hemolysis or organ damage. Lymphadenopathies, arthralgias, fevers or even vasculitides are not IgE-mediated and are assessed as unusual reactions.

Risk factors for hymenoptera venom allergy

The risk of having a systemic reaction again after a mild general reaction and after another hymenopteran sting is about 30%, whereas after a severe reaction it is between 50 and 70% [2-4, 7]. Children generally have a lower risk of relapse than adults. Older individuals tend to have more severe general reactions due to pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary disease [3, 12]. Beta-blocker and ACE inhibitors can also negatively affect the severity of a general reaction and its therapy [13, 14].

In recent years, an association between elevated basal serum tryptase and the occurrence of general allergic reactions after insect stings has been confirmed several times [15, 16]. An elevated basal tryptase level (>11.4 µg/l) is found in about 10% of patients with a general reaction after a hymenopteran sting. Cutaneous mastocytosis is found in some and systemic mastocytosis in others. Basal tryptase levels >20.0 µg/l increase the likelihood that systemic mastocytosis is present [2–4]. It is estimated that about one third of patients with mastocytosis have an allergic reaction after an insect bite.

Diagnosis and problem of the test results

The basis for the diagnosis of a general reaction after an insect bite is the clinical symptoms together with the medical history. Typical in an allergic reaction are the occurrence of acute symptoms such as urticaria, angioedema (e.g., Quincke’s edema), acute respiratory distress, general weakness, or shock [2-4, 7]. An allergic mechanism is confirmed by skin or in vitro tests (specific IgE antibodies) [2, 3, 7]. If allergological clarification is performed within twelve months of a systemic reaction, IgE-mediated sensitization to the corresponding insect venom can be detected in nearly 100% of cases [2, 3, 7]. However, the specificity of these tests is limited because even individuals without allergic symptoms show sensitization in up to 25% even years after a hymenopteran sting. It should be known that sensitization is usually triggered by a normally tolerated insect bite. After a general reaction, the clarification should take place after three to four weeks.

About half of all patients with insect venom allergy have double positivity, with evidence of specific IgE antibodies to bee and wasp venom [2, 3, 9]. This may be a true sensitization to both venoms or cross reactions due to partial sequence identities of protein allergens or IgE antibodies against carbohydrate determinants of allergens (so-called “cross reactive carbohydrate determinants”, CCD) [17]. A distinction is important in that in the case of true double sensitization, specific immunotherapy with bee and wasp venom should be given.

Commercial determination of specific IgE antibodies against recombinant, species-specific major allergens (Api m1 for bee, Ves v5 and Ves v1 for wasp) has been available for a few years (Immuno-CAP®, Phadia AG, Thermo Fisher Scientific) [18, 19]. While the sensitivity and specificity of Ves v5 and Ves v1 are good, the sensitivity and specificity of the main allergen Api m1 alone is not optimal [18].

In these situations, allergists often consult an additional in vitro test, namely the basophil activation test (BAT), as a further diagnostic aid. However, the validity of this test is not unconditionally superior to the others. Rarely, despite a suggestive history, the allergological test may be doubly negative, so that occasionally a test is repeated. However, in the case of repeatedly negative diagnostic tests, the implementation of specific immunotherapy is generally not indicated. An exception may be mastocytosis in documented anaphylaxis following a bee or wasp sting [2].

Specific immunotherapy with hymenopteran venoms

In recent decades, specific immunotherapy with bee or wasp venom has proven to be the only causal and effective treatment for insect venom allergy [2, 3, 20, 21]. While over 95% of wasp venom allergy sufferers are fully protected in the event of a repeat wasp sting, this is only the case for around 80% of bee venom allergy sufferers. Nevertheless, even with partial protection, the general reactions are often much weaker than in the index reaction that gave rise to immunotherapy. It is possible that the lower efficiency of immunotherapy in bee venom allergy is related to the fact that at least one of the bee venom allergens (Api m10 and Api m3) is not present in the therapeutic solutions or is present only in low concentrations [10]. According to guidelines, both in Europe and in the USA, specific immunotherapy with insect venoms is indicated in the presence of a severe general reaction with respiratory and/or cardiovascular symptoms and a positive diagnostic test [20, 21]. Given the low risk of severe general reaction after only skin reaction in children and adults, the indication of immunotherapy is performed only in case of high exposure or special risks. Severe local reactions are only rarely considered an indication for immunotherapy, even with positive diagnostic tests.

Contraindications to specific immunotherapy with insect venoms are the same as for other immunotherapies (e.g., pollen or dust mite allergy) [2, 3, 20, 21]. Allergic general reactions associated with immunotherapy with insect venoms are observed with varying frequency, usually occurring in the initiation phase. They are registered more frequently with immunotherapy using bee venom than wasp venom and more frequently with the Ultrarush protocols than with the conventional induction procedures [2, 3]. The risk of an immunotherapy-associated adverse event is increased if the basal serum tryptase level is above the upper reference range (>11.4 µg/l) or if mastocytosis has been diagnosed.

Duration of specific immunotherapy

In general, it is recommended that immunotherapy with insect venoms be safely administered for three to five years because this makes the “vaccine protection” last longer [2, 3, 20, 21]. Prolonged or even lifelong immunotherapies should be considered especially in patients with severe general reactions, chronic cardiac or pulmonary disease, or in patients with elevated basal serum tryptase or mastocytosis [12].

Prevention and allergological clarification

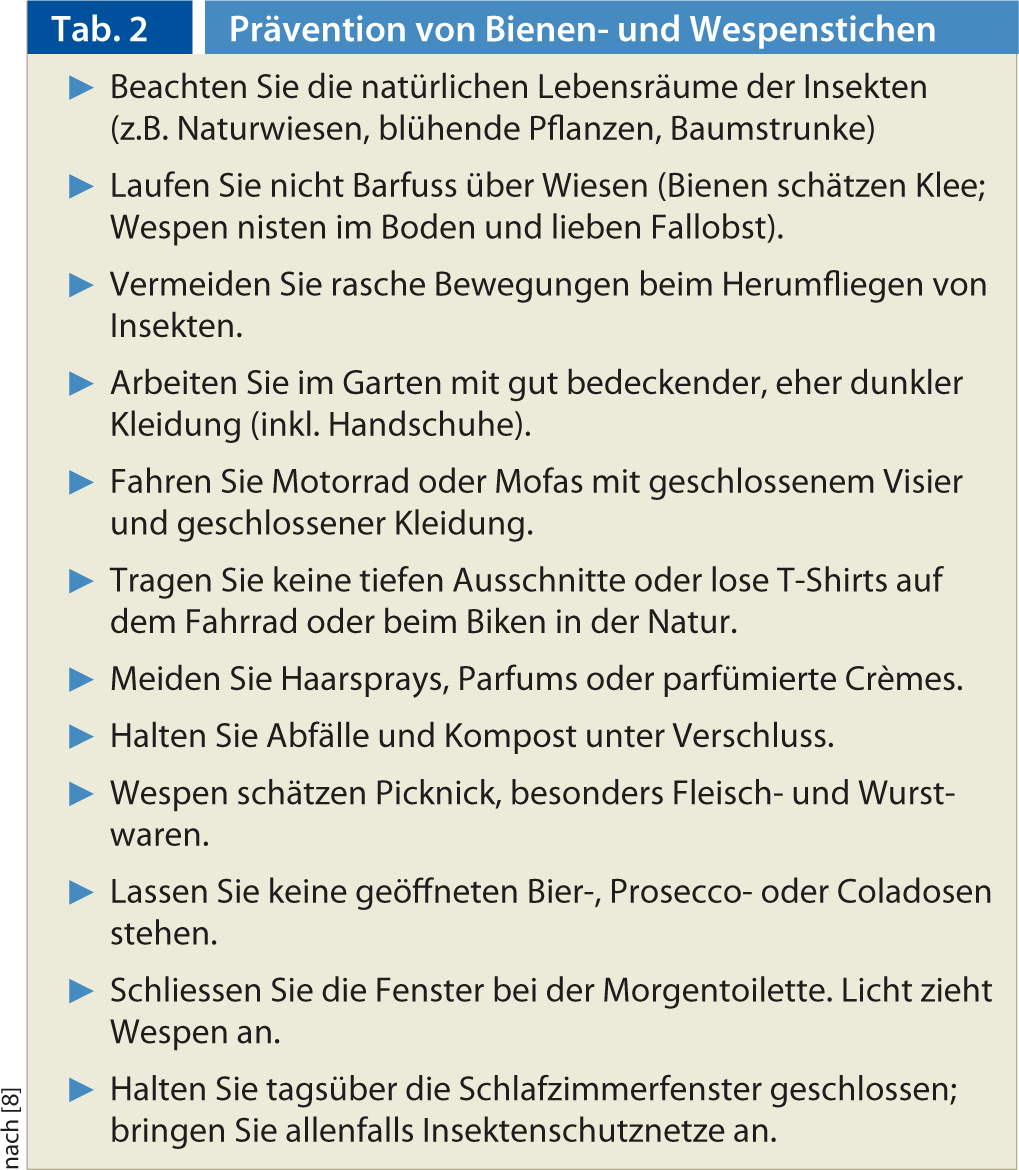

There are a few recommendations on how we can all beware of hymenopteran stings that should be taken to heart when coming into contact with the insects(Table 2) [2, 3, 20, 21]. All patients with a generalized reaction, even if it was not life-threatening (e.g., generalized urticaria), should be equipped with an emergency medication kit (e.g., cetirizine and corticosteroid 50 mg 2 tablets each) and an epinephrine auto-injector (e.g., Epipen® or Jext®) [22]. For children up to twelve years of age, one tablet each is usually sufficient; however, the epinephrine auto-injector should be prescribed based on weight (<30 kg: 0.15 mg; >30 kg: 0.3 mg) [22]. It is very important that patients are properly instructed in its use. The recommendation is justified by the fact that in the event of a renewed general reaction after a sting, the severity cannot be predicted. It is also true that not every sting has to lead to an allergic reaction, even if you have had an allergic reaction before! Nevertheless, we can all be at risk. Every patient should be evaluated allergologically after a systemic reaction because, if necessary, a high level of safety protection can be achieved by means of specific immunotherapy in case of re-exposure.

Conclusion for practice

- The frequency of hymenoptera venom allergy in Switzerland is between 3 and 4%; nobody is immune to it!

- The sting reactions can lead to various clinical

- lead to a change in the appearance of the product.

- The risk of becoming allergic again after a renewed sting

- reaction is around 30% after an initial mild general reaction, and between 50 and 70% after a severe reaction.

- After a general reaction, every patient should receive emergency medication and be clarified allergologically.

- By means of specific immunotherapy with hymenopteran venoms, a high degree of safety protection against re-exposure can be achieved.

Prof. Arthur Helbling, MD