Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic, progressive liver disease characterized by the histologic picture of interface hepatitis, hypergammaglobulinemia, and circulating autoantibodies. AIH occurs in all age groups and affects women more often than men (3:1 ratio). The spectrum of AIH ranges from asymptomatic disease to acute or even fulminant hepatitis, to liver failure. Corticosteroids are used for remission induction. In maintenance therapy, azathioprine is preferred to reduce the risk of recurrence for at least two, preferably four years.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) accounts for 11-23% of all chronic hepatopathies. The incidence may be underestimated because viral hepatitis is common and when chronic viral hepatitis is present, autoimmune hepatitis, which may be concurrent, remains undetected. The annual incidence in Caucasians is 0.1-1.9/100,000, and the prevalence is 16.9/100,000 [1]. AIH is responsible for 2.6% of liver transplants in Europe [2] and for 4-6% of liver transplants in the United States [3]. Women are about three times more likely to be affected. In principle, the disease occurs in all age groups, but in 50% of all cases, the disease begins before the age of 30.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of AIH remains unclear. The clinical picture reflects a complex interaction between genetic predisposition, trigger factors, autoantigens, and immunoregulatory mechanisms, ultimately resulting in an immunologic (cell-mediated, antibody-mediated, or combination) process against hepatocytes with development of chronic inflammation leading to cirrhosis. Exact trigger factors are unknown; infectious, drug, and toxic agents are all possible. A molecular mimicry of foreign and self antigens is the most common explanation for the loss of self tolerance [4].

Clinic

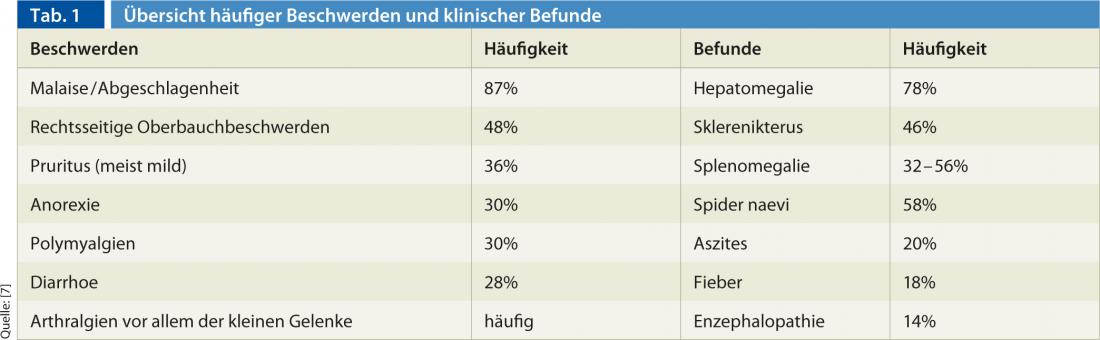

The AIH has a very heterogeneous and fluctuating appearance. The diagnosis is often delayed because often only mild, nonspecific symptoms of acute, self-limiting hepatitis are present. Table 1 provides an overview of typical complaints and clinical findings [5].

There are different forms of manifestation, which are briefly discussed below:

- Asymptomatic: Diagnosis is made based on incidental findings of elevated liver enzymes in asymptomatic patients.

- Acute hepatitis: acute onset in approximately 40% of cases. A detailed history often reveals earlier nonspecific symptoms such as episodes of malaise, nausea, and arthralgias.

- Acute liver failure: in rare cases, initial presentation as fulminant hepatitis (5%) or hepatic decompensation (“burned-out disease”) with ascites (20%), hepatic encephalopathy (14%), and bleeding esophageal varices (8%).

- Liver cirrhosis: Up to 30% of initial diagnoses as liver cirrhosis or with corresponding complications.A typical feature of AIH is its association with extrahepatic immune-mediated syndromes such as autoimmune thyroiditis, vitiligo, alopecia, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and glomerulonephritis.

Division

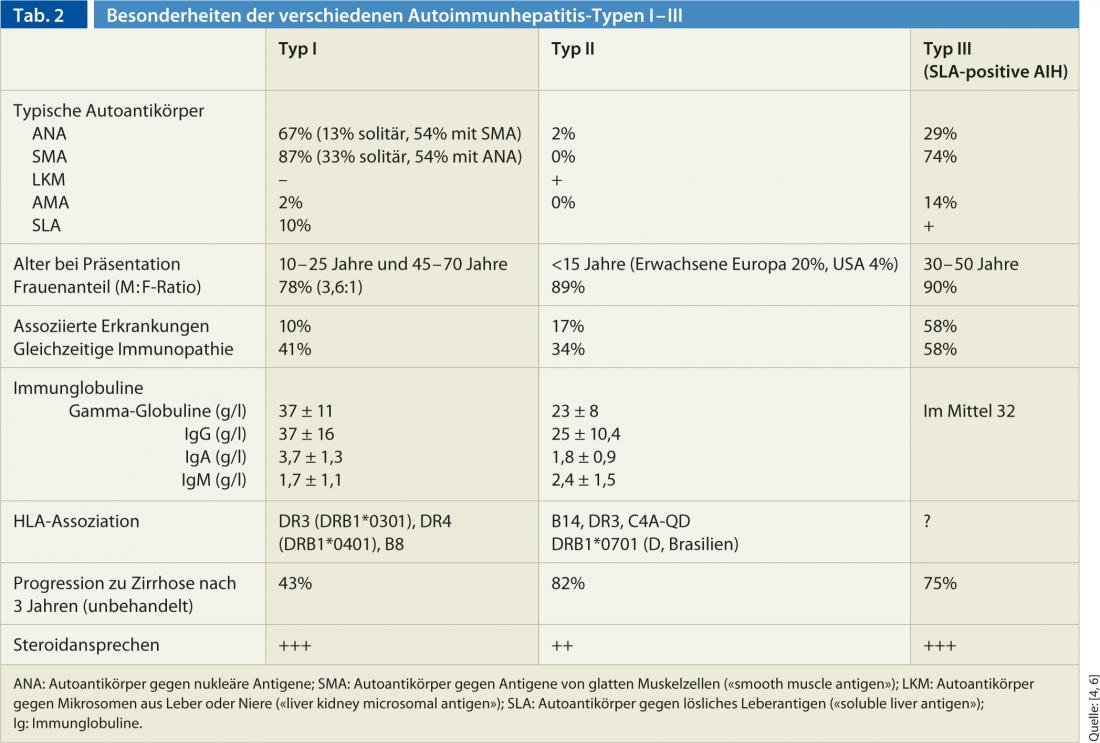

On the basis of antibody constellation, AIH is classified into three different types (type I-III) (Table 2). Type I AIH is the “classic” AIH and most common form worldwide. In comparison, type II AIH is rare and primarily affects pediatric patients (girls/young women). The occurrence of AIH may occur in combination with other autoimmune diseases of the liver (so-called “overlap syndromes”). AIH most commonly overlaps with AMA-positive primary biliary cirrhosis (approximately 88%), but primary sclerosing cholangitis and viral hepatitis may also be present concurrently.

Diagnostics

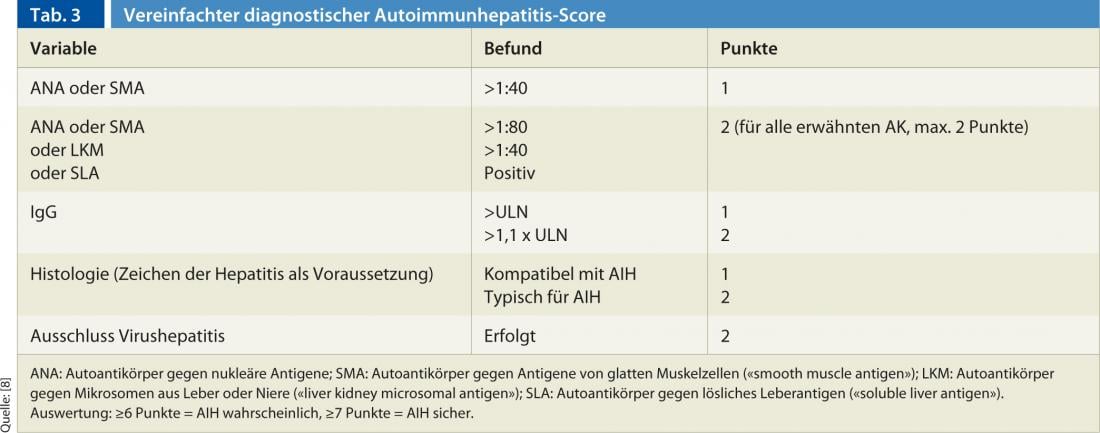

The diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical, histologic, and serologic findings, as well as the exclusion of other chronic hepatopathies (primarily viral hepatitides, drug-induced hepatitis, hereditary and metabolic hepatopathies) [7]. No single finding by itself is pathognomonic for AIH. For this reason, several scores have been established in the past, with the recently published and simplified score by Hennes et al. is easy to handle in everyday clinical practice [8]. The score distinguishes between a definite (min. 7 points) and a probable (min. 6 points) diagnosis of AIH based on the following four criteria (Table 3):

- Presence of autoantibodies

- Elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG)

- Liver Histology

- Exclusion of viral hepatitis

The sensitivity and specificity of this score are high: for a definitive diagnosis, scores of 81% and 99%, respectively; for a probable diagnosis, 88% and 97%, respectively [8].

Laboratory: Laboratory chemistry tests usually show the typical picture of hepatocellular liver damage: transaminases are significantly higher than cholestasis parameters (AST: ALP ratio >3). A cholestatic picture with predominant direct hyperbilirubinemia and ALP elevation is less common. In addition, if AIH is suspected, gamma globulins and autoantibodies to nuclear antigens (ANA), smooth muscle antigen ( [SMA]), and liver or kidney microsomal antigen ( [LKM]) should be determined.

More recent additional autoantibodies include antibodies to liver cytosol 1 (LC-1), whose titers correlate with the inflammatory activity of AIH, or asialoglycoprotein receptor antibodies (ASGPR). These can be detected in up to 90% of type I AIH and have prognostic significance.

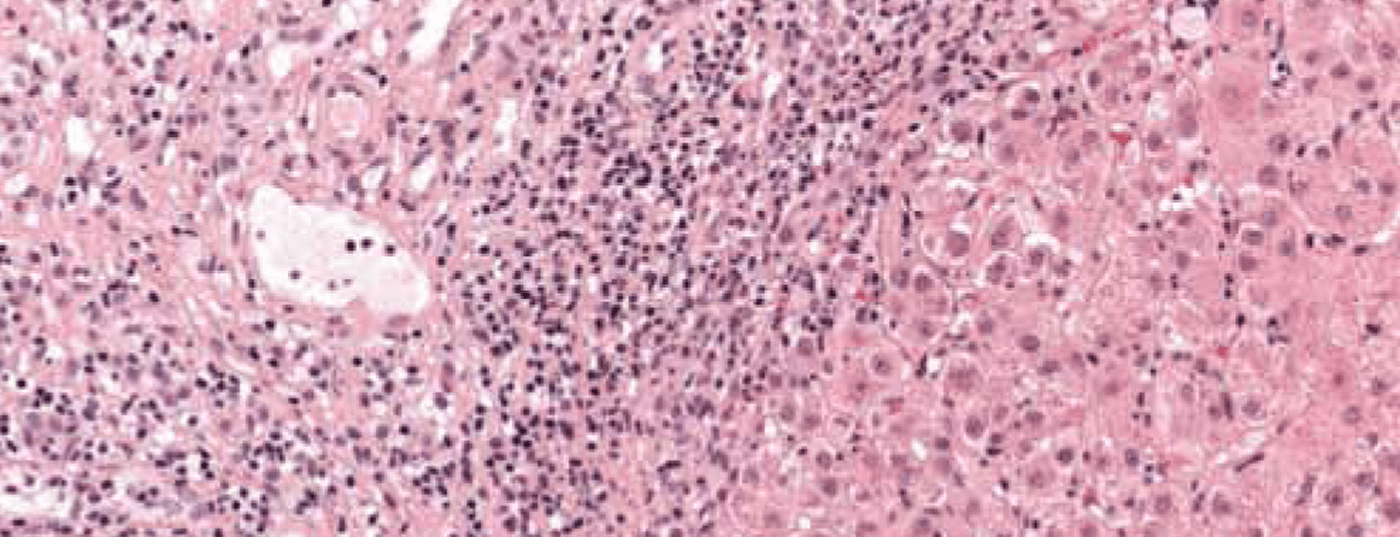

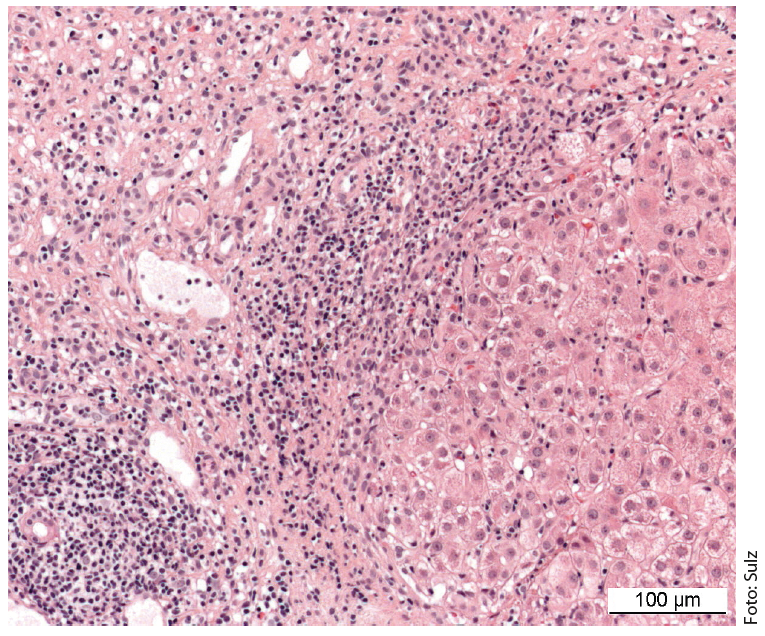

Histology: Histology is essential to establish a definite diagnosis, even if histologic findings are not specific for AIH [5]. Even when the clinical presentation is acute, signs of chronic hepatopathy are usually already present histologically. Histologic expression does not correlate with the degree of elevation of liver enzymes or IgG. Histology is thus a more reliable parameter than laboratory findings for estimating the severity of the disease [9].

Characteristic is the picture of a chronic necroinflammatory disease: portal and periportal (“piecemeal necrosis”, “interface hepatitis”) as well as monocytic (lymphoplasmocytic) infiltrates (Fig. 1). In severe, advanced disease, extensive bridging necrosis and fibrosis are present. Interface hepatitis does not necessarily indicate progressive disease, whereas bridging necrosis increases the likelihood of progression to cirrhosis. The specificity of the overall histologic findings is 81%, and the positive predictive value is 68%. Consequently, differentiating drug-induced or even viral hepatitis from AIH can sometimes be difficult.

Fig. 1: Liver histology of a 12-year-old girl shows partially fibrosed portal field sections with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrates and active interface hepatitis. Staining: hematoxylin-eosin.

Therapy

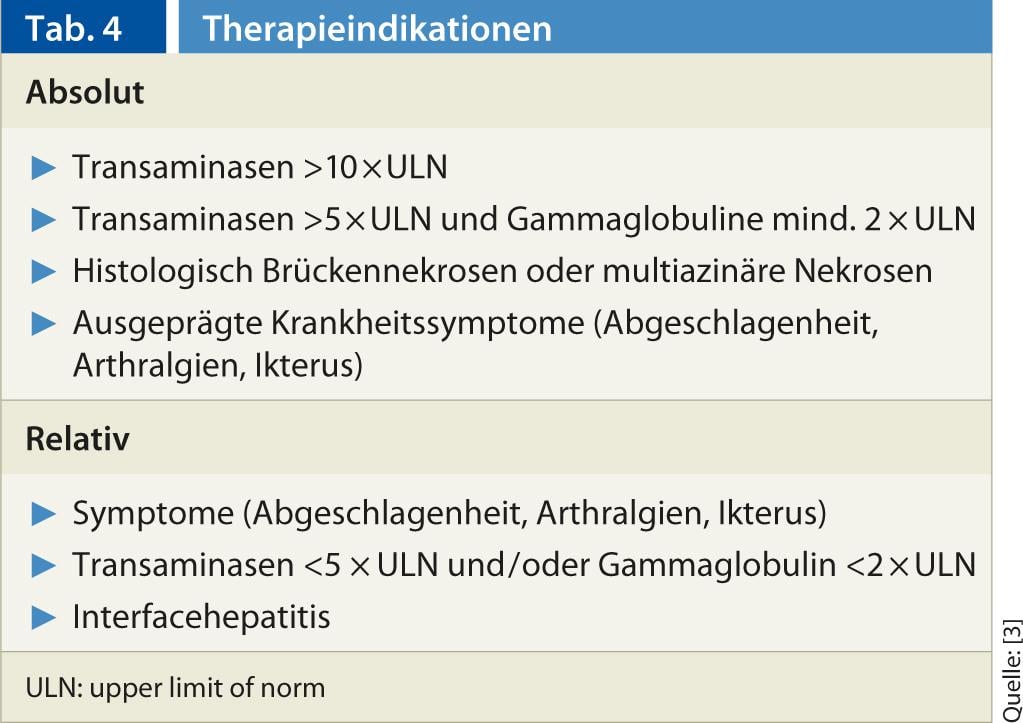

Indications: According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), there are absolute and relative indications for the treatment of AIH (Table 4) [3].

Classification of therapy: Therapy can be divided into different phases:

- Remission induction

- Remission maintenance

- Tapering or discontinuation

- Therapy of a recurrence

Therapeutic goal: The goal of therapy is permanent remission. Classically, remission is defined as a decrease in AST <2 times the upper norm and normalization of gamma globulins [8]. However, recent studies indicate that complete normalization of liver enzymes, histology, and gamma globulins should be the goal of therapy, as this has improved the prognosis of treated patients [10, 11].

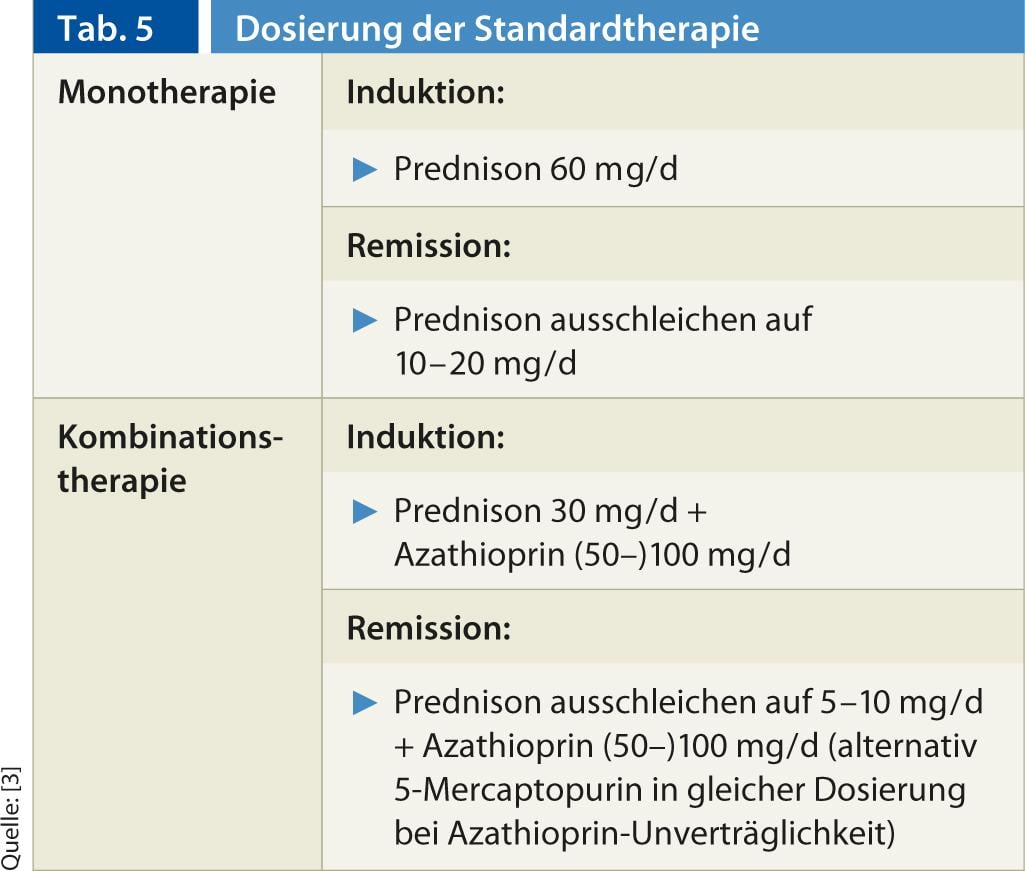

Standard therapy: In immunosuppressive therapy for AIH, collaboration between the primary care provider and a specialist has proven effective. Currently, standard therapy consists of monotherapy or combination therapy with prednis(ol)-one with/without azathioprine, based on prospective, non-randomized studies from the 1960s to early 1980s. The dosage regimens are mentioned in Table 5. It is important that the steroid dose should not be reduced too quickly. Transaminase normalization should be awaited. In the case of steroid/thiopurine combination therapy, azathioprine is rapidly added to the steroid. If azathioprine is intolerant, it can be switched to 5-mercaptopurine (Puri-Nethol) at the same dosage. The efficacy of combination and monotherapy is comparable, but combination therapy is steroid-sparing, associated with less severe steroid side effects (from 66% to <20% during 18 months of therapy) [12].

Alternative therapy with budesonide: In the largest controlled therapy study to date on AIH, the value of budesonide (3 × 3 mg) was compared with prednis(ol)-one in each case in combination with azathioprine [13]. Both study arms showed a relatively low rate of complete remission, but significantly fewer steroid side effects in the budesonide group (28% vs. 53%). Budesonide (2 × 3 mg) also appears to be well suited for remission maintenance.

However, portal hypertension or cirrhosis is a relative contraindication to budesonide due to reduced metabolism [14].

Remission and relapse significance of sufficient duration of therapy: remission is achieved in 65-75% of cases after 24 months of therapy. About 20% do not achieve complete remission. Recurrence (increase in transaminases and/or symptoms during therapy or during tapering or after discontinuation of therapy) occurs in approximately 50% of cases within six months and in 80% after three years after discontinuation of therapy, associated with progression to cirrhosis in nearly 40% and development of liver failure in 14%.

The duration of therapy before discontinuation of immunosuppression seems to be the main factor in distinguishing patients in sustained remission from patients with relapse. Compared to the sustained remission of 67% with therapy >4 years, this rate is only 10% with therapy of 1-2 years [15]. Therefore, discontinuation of therapy is recommended only on the basis of complete clinical, histological and biochemical remission after two, preferably four years at the earliest. Histologic remission may be delayed by up to eight months compared with clinical and biochemical remission.

Newer therapeutic options (“second line”): Alternative therapeutic options should be discussed in the following cases:

- Therapy failure under standard therapy

- Intolerance of standard therapy

- Avoiding steroid side effects in high-risk patients.

- Experimental studies

Among others, mycophenolate, mofetil (MMF), tacrolimus or cyclosporin A are used here.

Liver transplantation: Liver transplantation should be considered early in cases of treatment failure. After successful transplantation, survival is good (5-year survival 91% [16]; 10-year survival 75% [cirrhosis: 62%]). The risk of recurrence in the graft is 20-36% [16] and is even more common in children.

Therapy monitoring and follow-up: Transaminases and the level of IgG indicate the success of therapy and should be determined regularly (three to six months). The determination of classical autoantibodies during the course is not useful, because the titer level does not correlate with the activity level. Liver biopsy is recommended before discontinuing therapy, as a residual inflammatory reaction in the liver may already indicate an increased risk of recurrence.

In the presence of cirrhosis, screening for hepatocellular carcinoma is recommended. Furthermore, patients with AIH should receive vaccination against hepatitis A/B as well as the usual standard immunizations [17].

Special therapy situations

High-risk patients: Risks for therapy side effects include: diabetic metabolic status, osteoporosis, poorly controlled arterial hypertension, emotional lability, or positive history for psychosis. These risk situations are not an absolute contraindication, but patients should be monitored closely and steroid-sparing agents such as azathioprine should be used sooner.

Fulminant hepatitis: while one small study failed to show a relevant benefit of steroids in fulminant AIH, steroid response in severe presentation was 36-100% in other studies. In general, if the presentation is fulminant, immediate referral to a transplant center is recommended [18, 19].

Cirrhosis: Patients with and without cirrhosis show a comparable good outcome (death and liver transplantation as endpoints) after ten years (10-year survival >90%), after which the survival curve of patients with cirrhosis (20-year survival <40%) drops significantly compared to non-cirrhotics (20-year survival <80%).

Decompensated cirrhosis: While the treatment benefit is unclear in histologically inactive cirrhosis, the treatment response in decompensated cirrhosis with active hepatitis may be very good. In some cases, regreening of fibrosis is also possible [20].

Forecast

Patients with AIH under adequate treatment have an overall normal life expectancy with well-maintained quality of life. However, approximately ¹⁄3 of AIH patients are already found to have complete liver cirrhosis at initial diagnosis, with a correspondingly poorer prognosis. With the exception of fulminant courses, liver transplantation can be avoided in almost all noncirrhotic patients and most patients with early cirrhosis.

Michael Christian Sulz, MD

PD Tilman J. Gerlach, MD

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- (AIH) accounts for 11-23% of all chronic hepatopathies, and the incidence may be underestimated.

- The exact pathogenesis of AIH remains unclear. The clinical picture reflects a complex interaction between genetic predisposition, trigger factors, autoantigens, and immunoregulatory mechanisms, ultimately resulting in an immunologic process against hepatocytes.

- AIH has a very heterogeneous and fluctuating presentation with different manifestations ranging from asymptomatic to acute hepatitis, to acute liver failure and cirrhosis.

- Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical, histologic, and serologic findings and exclusion of other chronic hepatopathies. The simplified score of Hennes et al. is easy to handle in everyday clinical practice.

- Therapy can be divided into different phases such as induction, maintenance of remission, tapering or discontinuation and therapy of a relapse.

- The goal of therapy is durable remission; standard therapy is monotherapy or combination therapy with prednis(ol)on with/without azathioprine.

Literature:

- Boberg KM, et al: Scand J Gastroenterol 1998; 33: 99-103.

- Milkiewicz P, et al: Transplantation 1999; 68: 253-256.

- Manns MP, et al: Hepatology 2010; 51: 2193-2213.

- Yeoman AD, et al: Hepatology 2009; 50: 538-545.

- Czaja AJ, Freese DK: Hepatology 2002; 36: 479-497.

- Sleisinger, Fordtran’s.: Gastrointestinal and Liver disease. 8th ed. Vol.2. Saunders, 2006.

- Krawitt EL: N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 54-66.

- Hennes EM, et al: International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Hepatology 2008; 48: 169-176.

- Czaja AJ, Wolf AM, Baggenstoss AH: Gastroenterology 1981; 80: 687-692.

- Miyake Y, et al: J Hepatol 2005; 43: 951-957.

- Montano-Loza AJ, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ: Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 1005-1012.

- Summerskill WH, et al: Gut 1975; 16: 876-883.

- Manns MP, et al: Gastroenterology. 2010; 139: 1198-1206.

- Geier A, et al: World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9: 2681-2685.

- Chancellor S, et al: J Hepatol 2001; 34: 354-355.

- Campsen J, et al: Liver Transpl 2008; 14: 1281-1286.

- Gleeson D, Heneghan MA: Gut 2011; 60: 1611-1629.

- Kessler WR, et al: Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2: 625-631.

- Czaja AJ: Liver Transpl 2007; 13: 953-955.

- Dufour JF, DeLellis R, Kaplan MM: Ann Intern Med 1997; 127: 981-985.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 5: 10-14