The treatment of bipolar disorder is one of the clinical challenges of a psychiatrist. In addition to efficient acute treatment, a sustainable long-term strategy is needed for the chronic recurrent courses. The latest guidelines of the German-speaking professional societies represent the current evidence for clinical practice.

Bipolar affective disorders are characterized by recurrent depressive and (hypo)manic episodes. The disorder, which often begins in young adulthood, is associated with relevant social limitations, a high risk of disability, and long-term neurotrophic brain changes if left untreated. Therapy is demanding and requires an integrative approach: in addition to in-depth psychoeducation, it involves treatment strategies that both treat the acute episode and have a prophylactic effect. The bipolar nature of the disorder must be taken into account. In view of the chronic relapsing course, long-term therapy requires not only effective agents but also agents with few side effects in the long term.

Both the Swiss Society for Bipolar Disorders (SGBS) and the German GeselIschaft für Bipolare Störungen (DGBS) have recently published updated guidelines for the professional treatment of bipolar disorders [1, 2]. While the German S3 guidelines include recommendations on all care issues based on a broad-based trialogical consensus process, the Swiss treatment recommendations focus on the currently evidence-based “first-line” treatments. The authors do not suggest treatments for failure of first-line therapies. The main recommendations of the Swiss Guidelines are reproduced below. Discrepancies with the German guidelines are pointed out in individual cases.

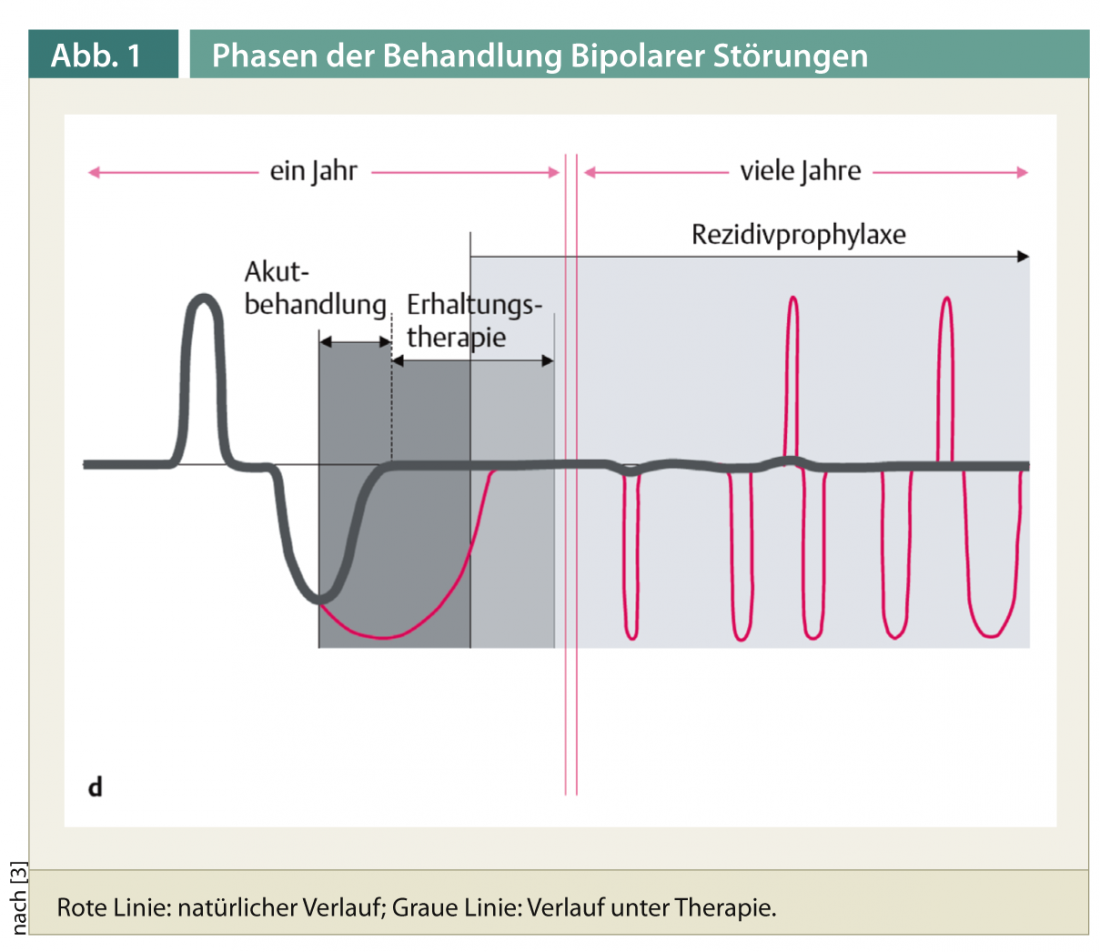

Treatment phases

Treatment begins with a careful assessment, which must lead to an evaluation of the risk potential and the indication of any immediate measures. The basis for further treatment is the establishment of a therapeutic relationship, the inclusion of the social environment and psychoeducation. A treatment concept must be worked out with the patient, comprising the following three phases (Fig. 1):

- The goal of acute treatment is the complete resolution of symptoms.

- This is followed by maintenance therapy: the continuation of acutely effective therapy for approximately six months to prevent relapse.

- Finally, relapse prevention is about preventing the occurrence of future episodes.

Depending on the acute or dominant phase, therapy is directed against phases of the disease of opposite nature: In mania, the focus is on drug therapy at the beginning, while in bipolar depression, psychotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic approaches are used from the beginning.

Psychoeducation and psychotherapy

Psychoeducation teaches a bio-psycho-social model of disorders that takes into account genetic factors, gene-environment interactions, and social and psychological influences on the initiation and course of the disorder. This approach serves as the basis of a multidimensional therapeutic concept ideally within a collaborative care model [4]. The aim is to optimize adherence (“treatment compliance”), which is to be regarded as a decisive factor for course and recurrence rate. Important elements of psychoeducation are the development of insight into the illness, education about the effects and undesirable effects of medication, recognizing and reacting to early warning signs, and the rhythmization of lifestyle. Psychoeducation can be provided in an individual or group setting. The involvement of relatives has proven its worth. Systematic psychoeducation can significantly reduce the risk of relapse [5].

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and family-focused therapy have proven to be effective psychotherapy methods [6]. These methods can improve interpersonal skills, personal stress management, and functional coping with the disorder and have a positive impact on acute and long-term outcomes.

Drug treatment

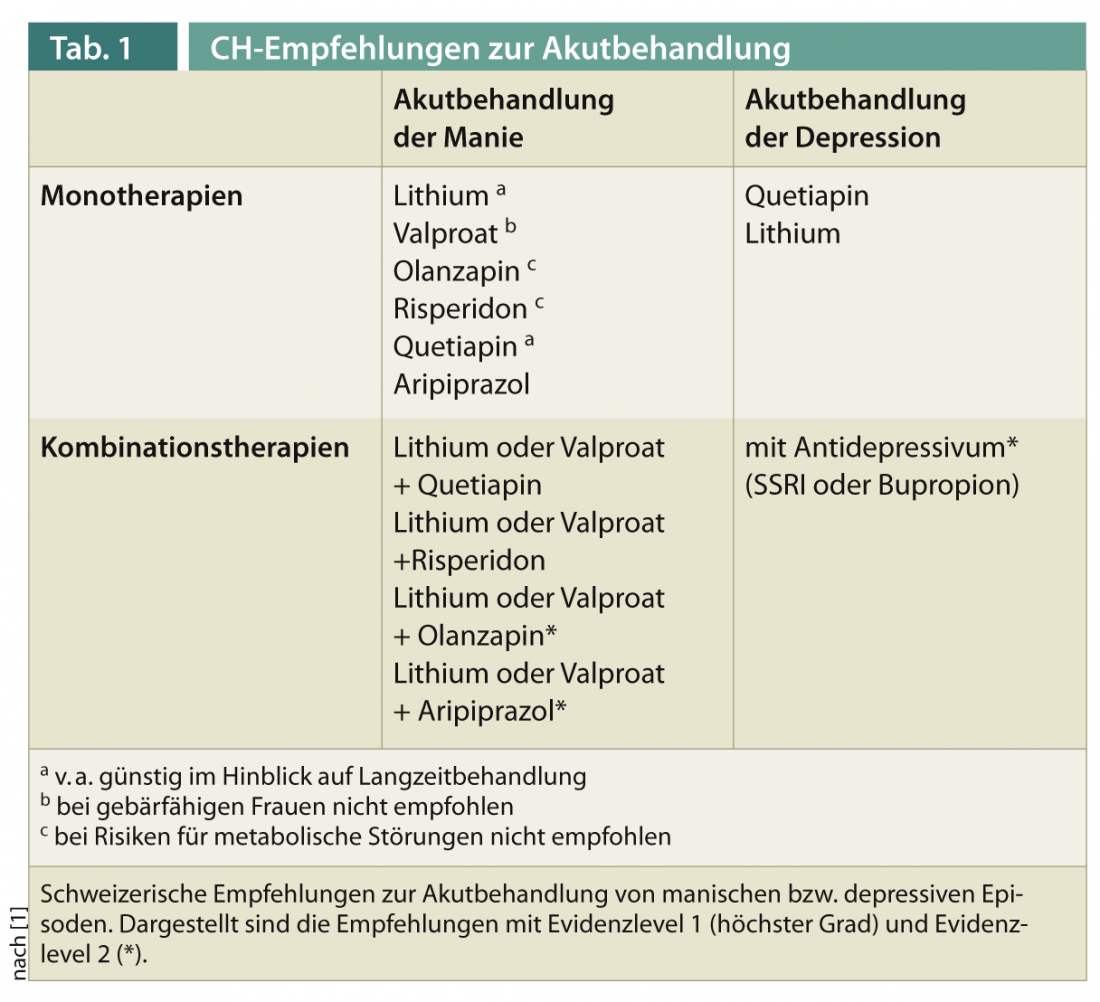

Acute treatment of mania: In recent years, the atypical antipsychotics listed in Table 1 have been shown to be effective in the treatment of acute mania.

Dosages are the same as for schizophrenia treatment. Because quetiapine and olanzapine have also been shown to have phase prophylactic effects, these antipsychotics offer advantages with respect to long-term therapy, although the risk of metabolic syndrome must be considered. Lithium shows a similarly good antimanic effect. In acute treatment, a plasma level >0.8 mmol/L may be necessary. Valproate has advantages over lithium in acute mania because of its rapid dosing and onset of antimanic action. Valproate also works well for mixed episodes. However, it should not be used in women of childbearing potential because of teratogenic risks. Finally, the combination therapies listed in Table 1 have been shown to be effective. However, effective monotherapy should be given primary preference.

Acute treatment of bipolar depression: quetiapine or quetiapine XR has been shown to be the first-line agent for acute treatment of bipolar depression according to several studies. The recommended dose is 300-600 mg per day. Furthermore, lithium or a combination with an antidepressant is recommended. The use of antidepressants in bipolar disorder is controversial. The likelihood of inducing a switch to (hypo)mania appears to be lower than previously thought. Antidepressants such as SSRIs or bupropion are considered safe and effective. According to recent reviews, the antidepressant efficacy of lamotrigine seems to be proven only in major depressive episodes [7]. The slow up-dosage makes it impractical for acute treatment.

relapse prophylaxis (Tab. 2): The efficacy of lithium in long-term therapy is well established. In the German S3 guidelines, lithium is the only drug with an “A” recommendation (highest recommendation class) for relapse prophylaxis. Lithium is superior to monotherapy with valproate as monotherapy and in combination with valproate [8]. A lithium plasma level of 0.6-0.8 mmol/L is prophylactic against both manic and depressive episodes. Another advantage of lithium is its suicide-preventive effect.

Of the atypical antipsychotics, in the Swiss Treatment recommendations Quetiapine received a “first-line” recommendation for long-term prophylaxis. The S3 guidelines do not yet include the most recent long-term study with quetiapine [9], which is why quetiapine is only recommended in combination with lithium or valproate for response in the acute treatment phase, and not yet as monotherapy. According to the decision criteria of the S3 guidelines, quetiapine monotherapy would now also be recommended as relapse prophylaxis on the basis of this study. Of the other atypical antipsychotics, both guidelines recommend aripiprazole, olanzapine, and depot injections with risperidone primarily for prophylaxis against manic episodes. In the Swiss guidelines, olanzapine is mentioned only with a level 2 recommendation because of the risk for weight gain and metabolic effects.

Valproate has received only a grade 2 recommendation in the CH guidelines due to the above comparison with lithium [8]. In Germany, due to the lack of long-term studies, valproate is only recommended for relapse prophylaxis in the case of a good response in acute mania. Valproate should be given to women of childbearing age only when strictly indicated, as it may cause malformations and reduced intelligence in the child.

Lamotrigine is mentioned in the CH guidelines with restrictions, i.e. primarily for depression prophylaxis in patients with hypomania. According to the German guidelines, it is also recommended for rapid cycling.

In relapse prophylaxis, combination treatments are common practice, although the evidence for this is not very high. There is a positive naturalistic study on combination treatment with lithium or valproate with quetiapine over four years [10].

A period of at least two to three years is recommended for the duration of relapse prophylaxis, although lifelong treatments may also be appropriate.

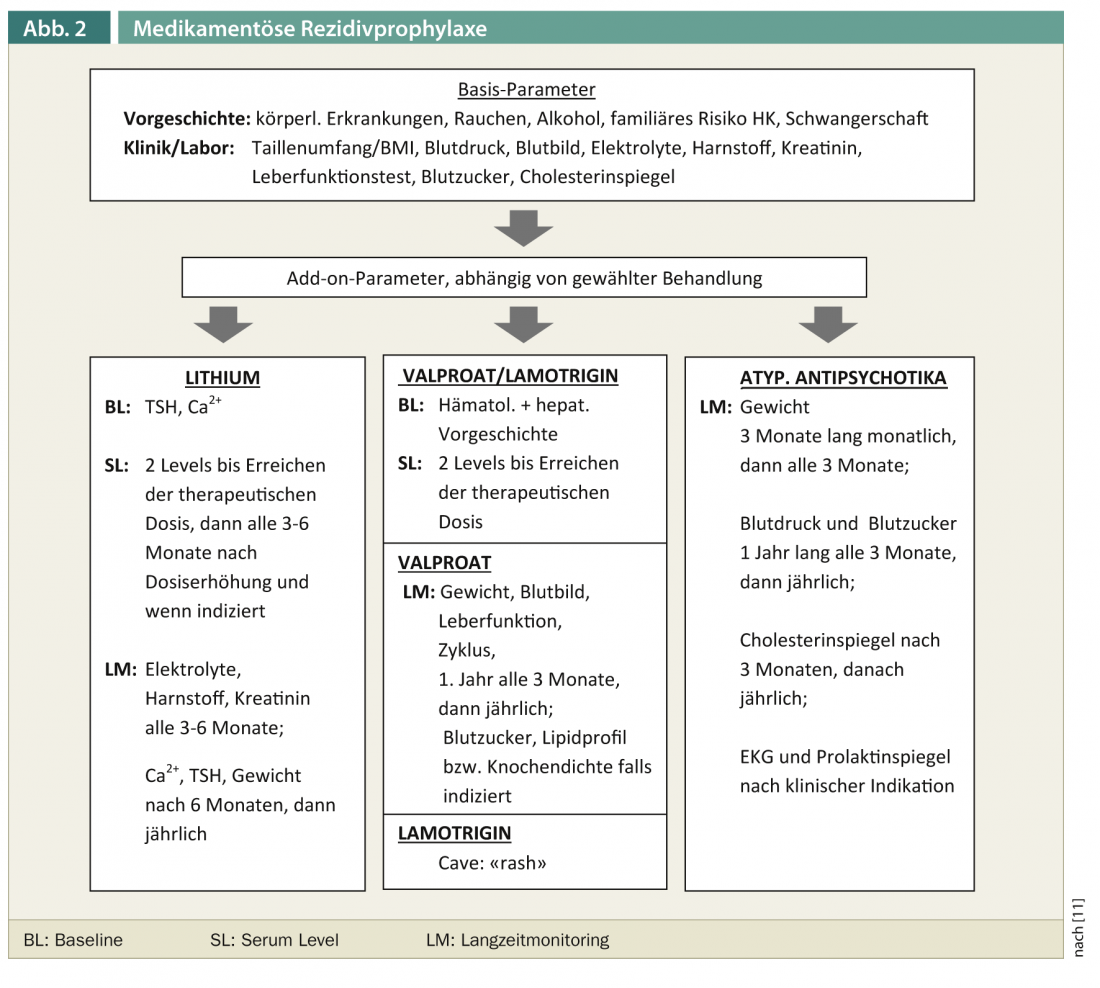

Laboratory controls and routine examinations

In view of the fact that drug therapy for bipolar disorder is often a long-term treatment and individual agents can have serious adverse effects in the long-term course, a careful baseline examination and regular checks of risk parameters are essential. Figure 2 shows a compilation of recommended laboratory controls [11].

Conclusions

Lithium is the “gold standard” for the treatment of bipolar disorder in both CH treatment recommendations and German S3 guidelines, with good antimanic, antidepressant, and suicide prophylactic properties and very good evidence for relapse prevention. Atypical antipsychotics are used as agents in the acute treatment of mania, in depressive episodes (especially quetiapine), and in relapse prevention. Individual medications have differential efficacies on the manic or depressive pole. An integrative therapy concept incl. Psychoeducation, specific psychotherapeutic interventions and involvement of relatives can significantly improve the long-term prognosis.

Thorsten Mikoteit, MD

Literature:

- Swiss Society for Bipolar Disorders. Hasler G, Preisig M, Müller T, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Conus P, Aubry JM, Greil W: Treatment recommendations for bipolar disorder. Switzerland Med Forum (2011); 11: 308-313.

- DGBS e.V. and DGPPN e.V.: S3-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie Bipolarer Störungen. Long version 1.0, May 2012.

- Greil W, Giersch D: Mood-stabilizing therapies in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness. A reference book for affected persons, relatives and therapists. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2006.

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, Parikh S, MacQueen G, McIntyre R, et al: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: consensus and controversies. Bipolar Disord 2005; 7(Suppl 3): 5-69.

- Rouget BW, Aubry JM: Efficacy of psychoeducational approaches on bipolar disorders: a review of the literature. J Affect Disord 2007; 98: 11-27.

- Miklowitz DJ: A review of evidence-based psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67(Suppl 11): 28-33.

- Calabrese JR, Huffman RF, White RL, Edwards S, Thompson TR, Ascher JA, et al: Lamotrigine in the acute treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10: 323-333.

- Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Rendell J, Azorin JM, Cipriani A, Ostacher MJ, et al: Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (BALANCE): a randomised open-label trial. Lancet 2010; 375: 385-395.

- Weisler RH, Nolen WA, Neijber A, Hellqvist A, Paulsson B; Trial 144 Study Investigators: continuation of quetiapine versus switching to placebo or lithium for maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder (Trial 144: a randomized controlled study). J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72: 1452-1464.

- Altamura AC, Mundo E, Dell’Osso B, Tacchini G, Buoli M, Calabrese JR: Quetiapine and classical mood stabilizers in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder: a 4-year follow-up naturalistic study. J Affect Disord 2008; 110: 135-141.

- Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, Sachs GS, Ferrier IN, Cassidy F, et al: The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord 2009; 11: 559-595.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2013; 11(1): 13-16.