The aim of the EMBARC study was to describe the clinical characteristics of bronchiectasis and compare them between different geographical regions. In a publication published in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine, analyses of a data set with over 16,000 patients are presented. Among other things, it shows that the use of inhaled corticosteroids in bronchiectasis patients without documented COPD or asthma appears to be widespread.

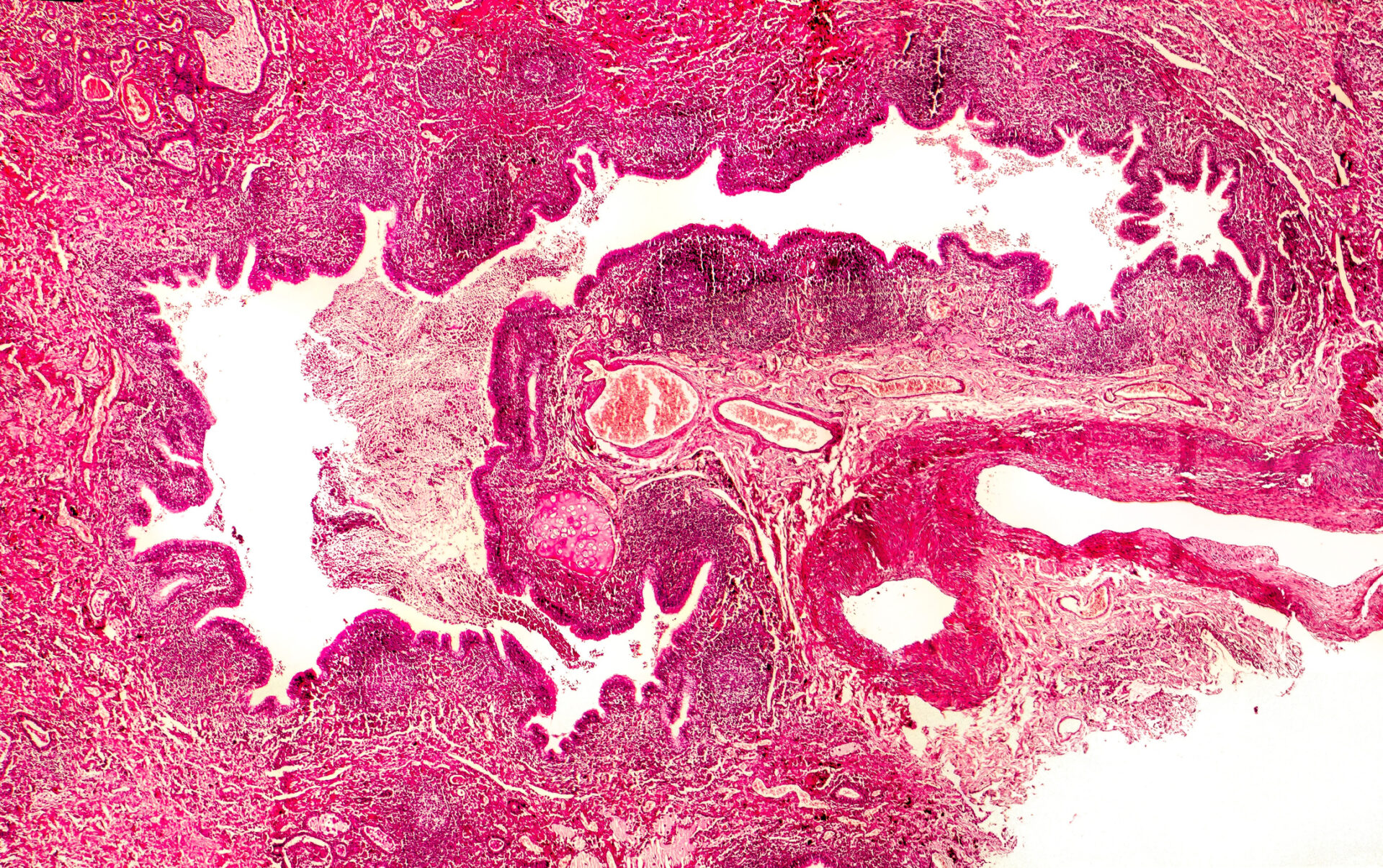

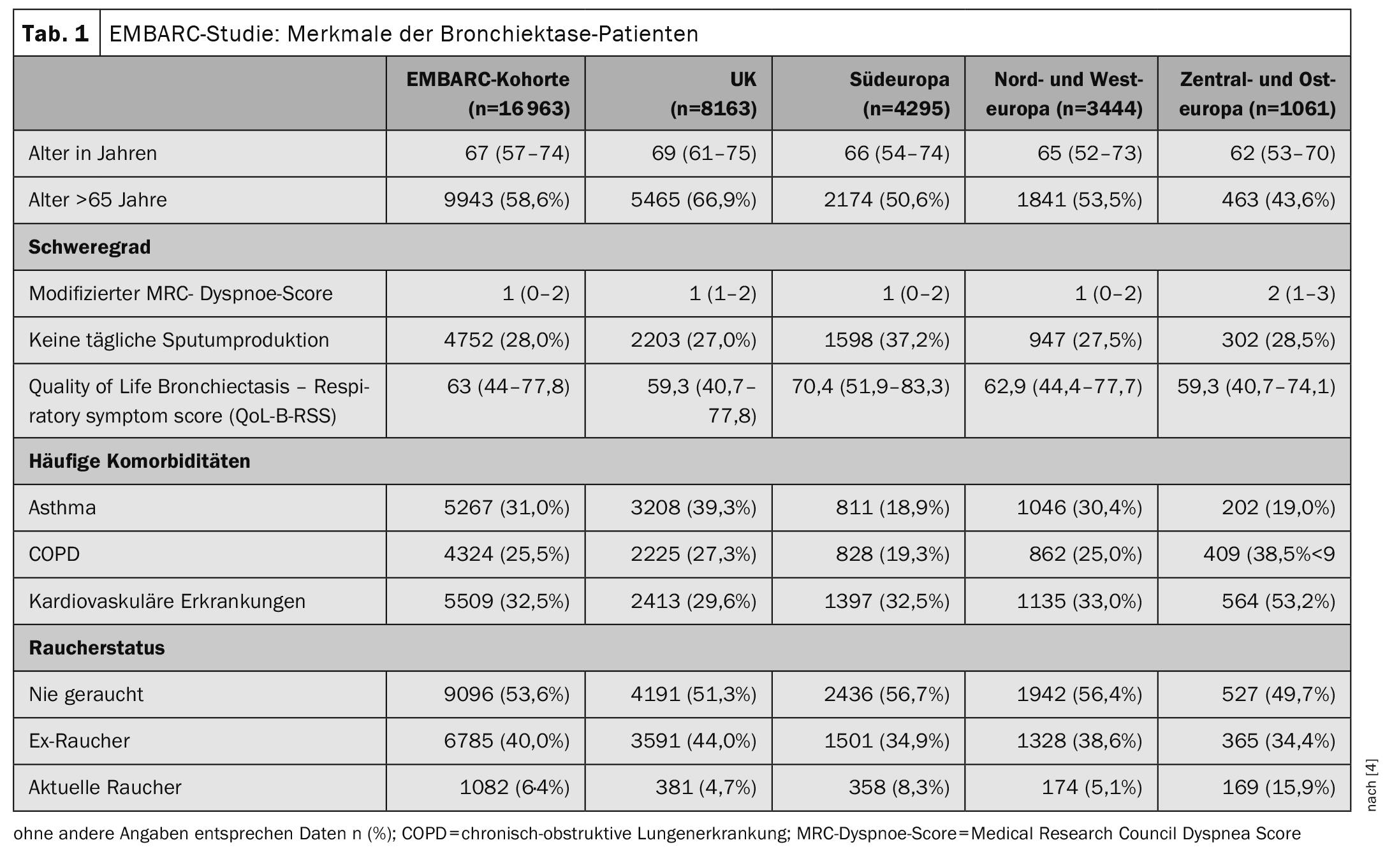

Bronchiectasis is the term used to describe an irreversible widening or bulging of a bronchus. Bronchiectasis occur preferentially in the dorsobasal sections of the lung and are often accompanied by inflammatory processes in the bronchus wall and surrounding tissue. Patients suffer from chronic cough, sputum production, shortness of breath, fatigue and recurrent exacerbations [1]. It is a heterogeneous disease for which there are still many unanswered questions. The most common causes of bronchiectasis are reported to be severe infections such as pneumonia and tuberculosis, but the prevalence of bronchiectasis has increased worldwide over the last 20 years, while the incidence of severe childhood infections and tuberculosis has decreased [2,3]. To date, there are only a few multicenter studies investigating the causes, severity, microbiology and treatment of bronchiectasis. In the period 12.01.2015-12.4.2022, 16,963 people were included in the EMBARC study [4]. The inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of bronchiectasis with a CT finding of bronchial dilatation (bronchoarterial ratio >1). Bronchiectasis due to cystic fibrosis and age <18 years were exclusion criteria. The average age of the study participants was 67 years (Table 1). 60.9% of the participants were female and 39.1% were male.

Important results at a glance

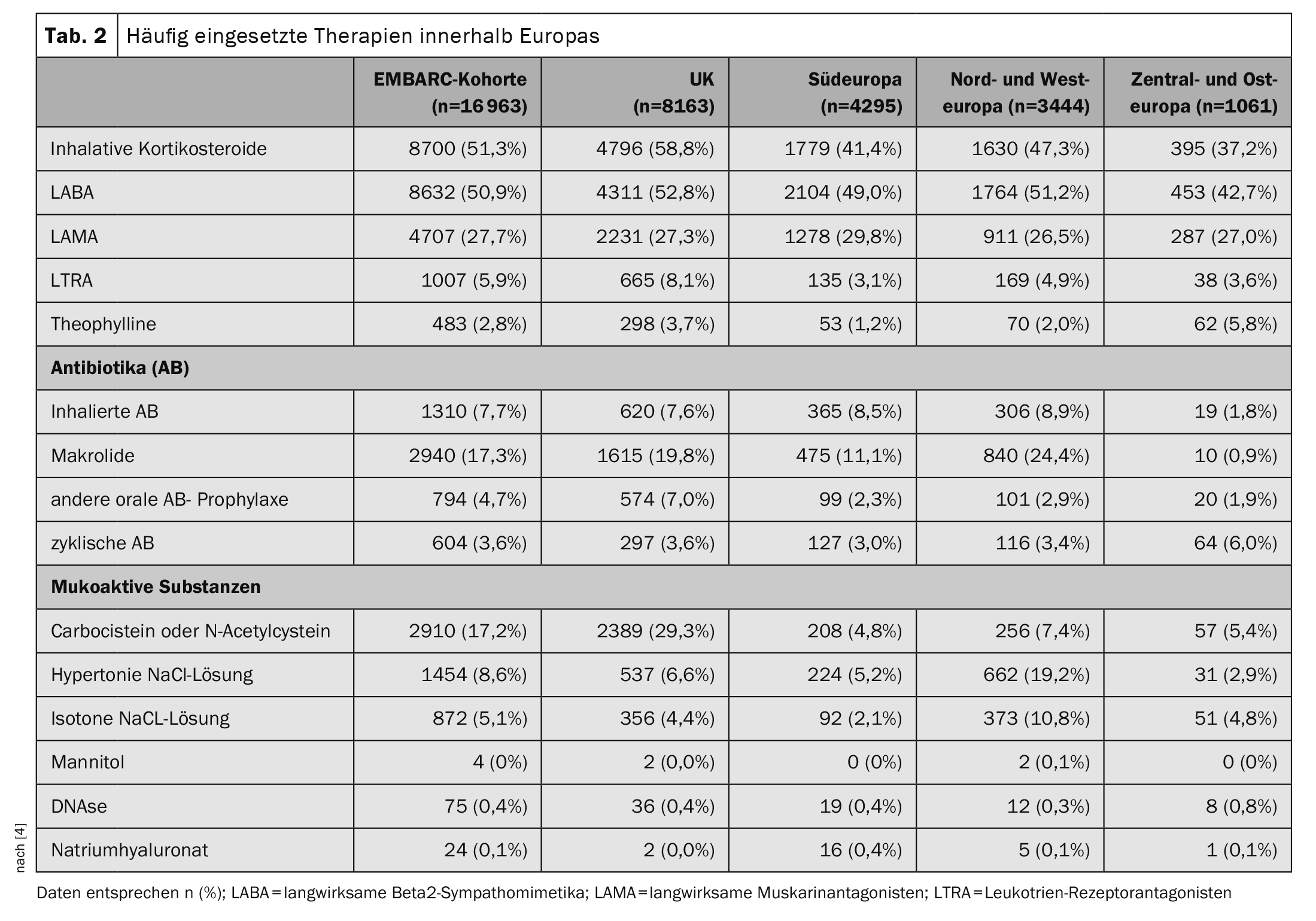

The most common identifiable cause of bronchiectasis in all 16 963 participants was post-infectious disease in 21.2%; in 38.1% the bronchiectasis was classified as idiopathic. A median of two exacerbations (IQR 1-4) occurred per year, and 4483 (26.4%) of patients were hospitalized for an exacerbation in the previous year. When analyzing the percentage of all bacteria isolated, significant differences in microbiology were found between different geographical regions, with a higher incidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and a lower incidence of Haemophilus influenzae in Southern Europe, compared to a higher incidence of H. influenzae in the UK and Northern and Western Europe. Compared to other regions, patients in Central and Eastern Europe had more severe bronchiectasis as measured by the Bronchiectasis Severity Index (51.3% versus 35.1% in the overall cohort) and more exacerbations leading to hospitalization (57.9% versus 26.4% in the overall cohort). Overall, patients in Central and Eastern Europe experienced more exacerbations in total** and exacerbations leading to hospitalization# were also more common than patients in other regions. The treatment of bronchiectasis varied greatly from region to region (Table 2) . This is not surprising given that there is no established standard of care and no approved therapies for bronchiectasis [5].

** Adjusted rate ratio [RR] 1.12; 95% CI: 1.01-1.25

# Adjusted RR 1.71; 95% CI: 1.44-2.02

Inhaled corticosteroids: benefit-risk considerations

The authors point out that it would be important for future clinical trials to understand whether the different phenotypes observed in the EMBARC study lead to differences in response to treatment in different regions. The available data shows that there are inequalities in access to treatment and treatment outcomes in Europe. This inequality is likely to be even greater worldwide. A striking finding of the present analysis was that inhaled corticosteroids were used by over 50% of patients with bronchiectasis in Europe and between one-third and one-half of all patients in most countries included in the EMBARC cohort used inhaled corticosteroids. According to the 2017 guidelines of the European Respiratory Society, inhaled corticosteroids are only indicated for patients with a history of asthma or COPD [5]. Inappropriate use of inhaled corticosteroids carries the risk of an increase in respiratory tract infections due to the proliferation of pathogenic proteobacteria, and the use of inhaled corticosteroids has been associated with an increase in pneumonia and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections [6]. Conversely, recent data suggest that 20-30% of patients with bronchiectasis may have eosinophilic inflammation, a type of inflammation that responds to treatment with inhaled corticosteroids [7].

Overall, the data from the EMBARC study suggest that clearer guidelines for the use of inhaled corticosteroids are needed and that it should be investigated whether biomarkers such as the eosinophil count in the blood can be used to guide the use of inhaled corticosteroids.

Literature:

- Hill AT, et al: Pulmonary exacerbation in adults with bronchiectasis: a consensus definition for clinical research. Eur Respir J 2017; 491700051.

- Quint JK, et al: Changes in the incidence, prevalence and mortality of bronchiectasis in the UK from 2004 to 2013: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 186-193.

- Ringshausen FC, et al: Increasing bronchiectasis prevalence in Germany, 2009-2017: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J 2019; 541900499.

- Chalmers JD, et al; EMBARC Registry Investigators. Bronchiectasis in Europe: data on disease characteristics from the European Bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC). Lancet Respir Med 2023; 11(7): 637-649.

- Polverino E, et al: European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017; 501700629.

- Keir HR Contoli M Chalmers JD: Inhaled corticosteroids and the lung microbiome in COPD. Biomedicines 2021; 91312.

- Shoemark A, et al: Characterization of eosinophilic bronchiectasis: a european multicohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: 894-902.

GENERAL PRACTITIONER PRACTICE 2024: 19(1): 28-29