What can we learn from medical historical sources? Traditional “louse remedies” are now used in mosquito control to reduce infectious diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever. They can also be used as anti-protozoal agents.

Louse infestation, whether on the head, on the body or in the pubic area, is an ancient scourge of mankind and as such also described early in medical textbooks. In Switzerland (especially if one is active in the school/care sector), one is particularly familiar with pediculosis capitis, a parasitosis caused by the head louse, which is frequently observed in children between three and eleven years of age, and here especially in girls. Side note: The “group selfie” generation is likely to have to contend with the problem increasingly soon, even in adolescence.

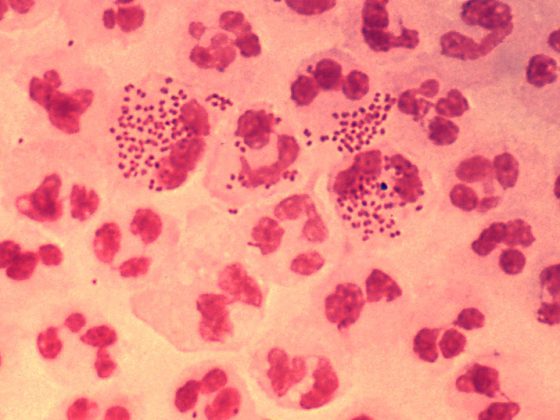

The main clinical feature after the incubation phase is pruritus with erythematous papules and wheals with potential bacterial super-colonization and regional lymphadenopathies. Sleep disturbances and consecutive mood swings and attention disorders may also occur. For the wingless little bloodsuckers, the human head provides an optimal habitat consisting of human hair and the appropriate humidity, temperature and oxygen conditions, as well as a blood meal every few hours (without which they quickly become dehydrated). During their adult life cycle of several weeks, they attach their eggs to the hair. The offspring in turn become capable of reproducing themselves after two to three weeks.

Although head lice are considered harmless in this country, as they generally do not transmit diseases in our latitudes, there is nevertheless a close relationship between head lice and clothes lice, probably also as potential vectors of bacterial pathogens. Clothes lice in particular are known to potentially transmit Rickettsia prowazekii, Borrelia recurrentis, and Bartonella quintana (causative agents of classical spotted fever, lice relapsing fever, and five-day fever). In times of war and famine, there have always been major epidemics in past centuries. Lice-borne infections may have been a problem not only in Napoleon’s army. There is also evidence earlier in the 18th century of an outbreak of typhus in Douai, France, in the context of the war taking place at that time (which also supports the hypothesis that the disease came to Europe from the Americas with Spanish soldiers). They are found – in contrast to head lice, which are primarily a sign of close social contact – especially in poor hygienic conditions. Crowded lounges, where people live close to each other in direct physical contact and with contaminated, rarely washed clothing and bedding, represent the insects’ preferred habitats. Classic spotted fever and louse relapsing fever are still prevalent today mainly in vulnerable populations in developing countries, while five-day fever is still found worldwide, for example, among homeless people. In addition, pathogens and parasites can be introduced across national borders.

Today’s treatment of pediculosis capitis

Widespread distribution, resulting extensive use of evidence-based (and non-evidence-based) treatments for head lice control, and excessive parental activism (absenteeism, scientifically unfounded excessive hygiene measures, etc.) drive up health care costs spent on the condition. Many myths and misconceptions still persist. According to current knowledge, it is considered extremely unlikely that head lice pass on to a new host via objects or clothing (rather, they are fast crawlers when in direct contact with hair), which makes cleaning headgear, cuddly toys, bedding, carpet, sofa or even the entire bed unnecessary, as well as shortening the hair, since even a few millimeters of hair give the eggs/nits sufficient hold. This is important information when advising affected families and should also be passed on by the family doctor in order to prevent unnecessary cleaning orgies and hygiene excesses.

Today, the combination of pediculocides and systematic combing out of damp hair is considered successful and evidence-based in the control of head lice. The latter is also used for diagnosis and verification of treatment success, although the interpretation of the result is not entirely simple and thus the sensitivity varies greatly (confusion of nits or empty egg cases with eggs, i.e. active infestation, or generally of combed-out artifacts with lice). Basically, one should always treat only when a live louse is found. Permethrin (Loxazol®) or also malathion (Prioderm®) are chemical pediculocides with proof of efficacy in controlled studies (but with observed resistance). Silicone (especially Hedrin® and Hedrin® Xpress), combined mineral oil (Elimax®, Paranix®), neem (Licener®) or alcohol-based products (Hedrin® Treat&Go) are physically effective pediculocides of proven efficacy as well. Most of these specifically exploit a “weak point” of the lice, namely their simply constructed respiratory system, e.g. by simply enclosing the lice like a film, penetrating their respiratory system and blocking it. The lice suffocate, can no longer regulate their water balance (they also release excess water vapor through the breathing holes) and dry out. The latter can also be achieved by damaging the shell of the louse, which is what Hedrin® Treat&Go uses, for example. Due to reduced side effects and the lack of resistance issues, physical pediculocides are now considered first-line agents. The treated can return to school, work, etc. directly after correctly performed therapy. However, it is necessary to repeat the procedure after about a week, because the effect of the products on eggs is different and generally limited.

Earlier treatment methods – current benefits

Mercury: Corresponding preparations were used (despite the enormous poisoning potential if used incorrectly) as antiseptics or laxatives and against syphilis. Topically, mercury was also used for pediculosis. In 1720 it was called “Neapolitanum” in combination with turpentine and lard. An effect against syphilis, scabies, bedbugs, but also phthiriasis was postulated. In the following century, ointments, rose water and lotions based on mercury remained popular in the fight against lice, also powders consisting of mercury bichloride, starch and sugar are described.

Unlike in the past, mercury is no longer used in the treatment of lice today – at least in Western medicine.

Delphinium Staphisagria (St. Stephen’s wort): Also used against lice (also crabs). Treatises from the 16th century see pediculosis primarily as an expression of poor hygiene (“bathing too infrequently”). If the problem cannot be controlled by frequent washing, staphisagria in combination with arsenic can be used in addition to mercury. Other authors from the 16th century agree, especially women would use it “to kill lice”, it was a “louse herb” of the Romans and is therefore called “herba pedicularis” in Latin. About adverse effects of the oil effective against phthiriasis resp. of the seeds on humans has also been reported. In the form of lotions and hot suds for hair washing, it should specifically kill head lice, but also crabs. In the 19th century it was further used as a powder in combination with sabadill, parsley and tobacco, as an ointment together with lard or as an infusion together with vinegar (pickling the seeds).

The traditional knowledge of the antiparasitic effect of St. Stephen’s wort has been translated into more recent studies on its efficacy against the pathogens of leishmaniasis (Leishmania infantum and braziliensis) and Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi), which are currently virulent mainly in Central/South America and Africa, but will soon become increasingly so in Europe as a result of global warming and mobility. According to current knowledge, the antiproliferative effect of Delphinium Staphisagria against T.cruzi (epimastigote, amastigote and trypomastigote forms) in some cases even exceeds that of the reference drug benznidazole – this with lower toxicity for the host [1]. Against L. infantum, which is also endemic in southern Europe, and against L. braziliensis (promastigote and amastigote forms), flavonoids of the aerial parts of the plant show activity without harming mammals – this in comparison with the reference drug glucantime, according to data from 2012 [2].

Sabadill: In the 19th century, sources on the use of sabadill in the field of pityriasis can be found. Moreover, many different preparations were known in the field of louse control, including (mentioned) powders containing sabadill seeds, staphisagria, parsley and tobacco, louse ointments made of sabadill powder, mustard, lard and pyrethrum, infusions for bed sheets (against bedbugs) or vinegar extracts. However, it also warned against use: if the skin in the affected area was injured, caution should be exercised (due to potential absorption through the skin and subsequent symptoms of poisoning). In any case, skin irritations could occur with certain preparations.

Even today, it is possible to use Sabadill preparations as insecticides against a wide range of insect species. The active components, the alkaloids, are located within the seeds.

Other: As mentioned in part above, parsley, Rhododendron tomentosum (marsh brier), (Virginian) tobacco, and perennial bergamot were also popularly used or used in preparations of all kinds in the 18th and 19th centuries. combined with the other louse active ingredients.

Whether oil of parsley also has potential as an insecticide against pyrethroid-sensitive and resistant Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) is being investigated today – the results are promising [3]. Rhododendron may serve as an effective repellent against the mosquito species. Aphids, small cicadas, mites, and fringe-winged insects are sensitive to Virgin tobacco, but its use as an insecticide has declined today due to its potential toxic and adverse effects on mammals and humans, and certain Leishmania pathogens, as well as Plasmodium falciparum (causative agent of malaria tropica) and Trypanosoma cruzi/brucei rhodesiense (the latter are causative agents of African sleeping sickness), possibly to bertam, which is now said to have an anti-protozoal effect, albeit slight [4].

Conclusion

Some well-known substances from traditional medical history have recently experienced a revival in the fight against diseases and disease vectors. In view of the undesirable toxicities of many pesticides, the development of resistance in vector insects, and unsatisfactory efficacy/side-effect profiles of some drugs, such “advice from the past” is highly welcome. The historical fund of observations, experiments and formulations is huge, but so is the interpretation of the effects or formulations. the causal traceability to a specific substance or by-products of the manufacturing process all the more difficult in some cases.

Sources:

- Vicentini CB, Manfredini S, Contini C: Ancient treatment for lice: a source of suggestions for carriers of other infectious diseases? Infez Med 2018; 26(2): 181-192.

- Feldmeier H: Pediculosis. Pediatrics 2017; 2: 39-43.

Literature:

- Marín C, et al: In vitro and in vivo trypanocidal activity of flavonoids from Delphinium staphisagria against Chagas disease. J Nat Prod 2011; 74(4): 744-750.

- Ramírez-Macías I, et al: Leishmanicidal activity of nine novel flavonoids from Delphinium staphisagria. Scientific World Journal 2012; 2012: 203646.

- Intirach J, et al: Antimosquito property of Petroselinum crispum (Umbellifereae) against the pyrethroid resistant and susceptible strains of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2016; 23(23): 23994-24008.

- Althaus JB, et al: Alkamides from Anacyclus pyrethrum L. and Their in Vitro Antiprotozoal Activity. Molecules 2017 May 12; 22(5). DOI: 10.3390/molecules22050796.

Further information: www.lausinfo.ch

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(11): 27-29