Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is an established therapy for the treatment of symptomatic heart failure and reduction of mortality in patients with left bundle branch block and extended medical therapy. The clinical response rate is around 70%. Patients with atrial fibrillation also benefit, provided that AV conduction can be controlled with medication or invasively (AV node ablation). Implantation of a CRT pacemaker reduces mortality. Since the majority of patients have a concomitant indication for implantation of an ICD, most patients receive a CRT-D. In elderly patients, end-of-life decisions are coming into focus in addition to symptomatic management of heart failure. Because CRT-D is associated with more complications and prevents possible sudden cardiac death compared with CRT-P, this difference must be explained to the elderly patient and the possibility of voluntary deactivation of the ICD must be pointed out.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has been a very successful treatment option for many patients with systolic heart failure who meet other specific criteria for more than ten years now. CRT is additive to optimal drug therapy, although the adjective “optimal” is not defined more precisely. In everyday life, it often means the maximum therapy still tolerated by the patient. Despite this extended pharmacological therapy, progression of heart failure on the one hand and ventricular arrhythmias on the other hand are the most frequent causes of death in patients with systolic pump failure and an ejection fraction (EF) of less than 35%. CRT may result in improvement and/or stabilization of symptoms and EF. If a CRT with defibrillator function (CDT-D) is implanted, sudden cardiac death can also be prevented. In principle, CRT should not be indicated differently in the elderly than in younger patients – the question is rather whether a CRT pacemaker (CRT-P) or a CRT-D should be recommended.

In the following, we therefore first address the question of when CRT is indicated at all, and then the question of model selection.

Indication for CRT

Approximately 25% of all heart failure patients have left bundle branch block, which is associated with an increased risk of further worsening of heart failure compared with unimpaired conduction. The delayed lateral wall excited by left bundle branch block (electrical dyssynchrony) contracts at a time when the septum is already in relaxation, which may lead to a relevant loss of ventricular function (mechanical dyssynchrony). Dyssynchrony itself further decreases EF and leads to the onset or worsening of mitral regurgitation and increased filling pressures.

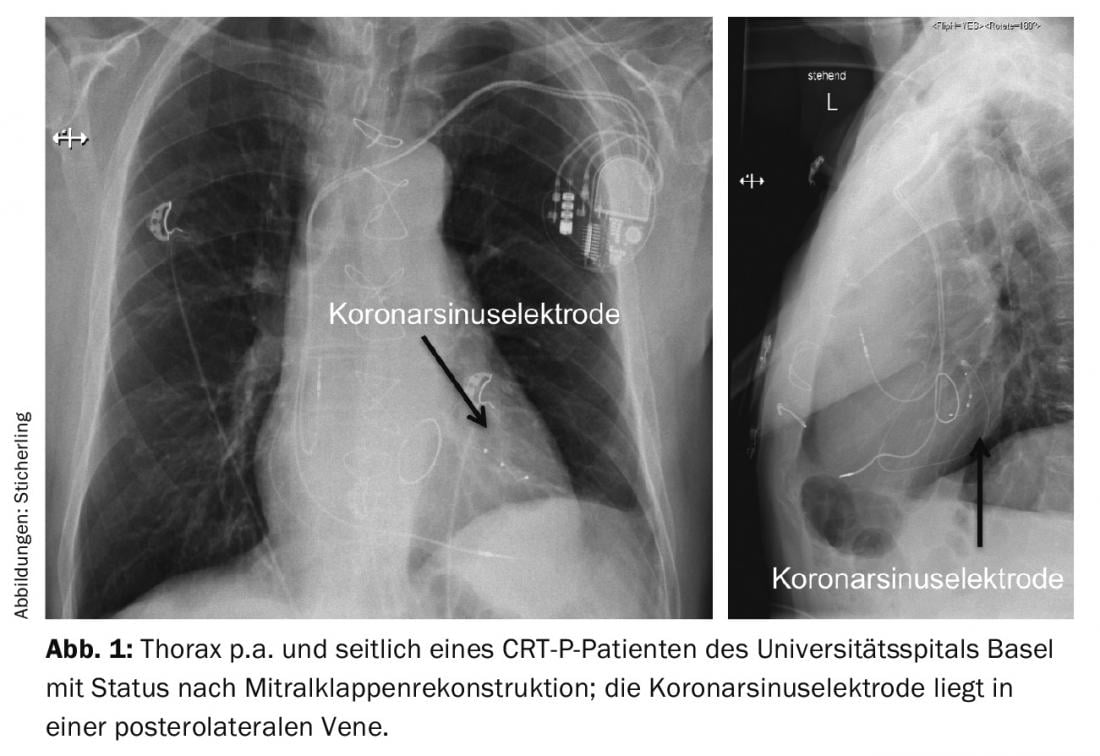

In many affected individuals, this dyssynchrony can be reversed by simultaneous pacing of both ventricles. The lead required for left ventricular pacing is usually implanted via the coronary sinus into a posterolateral epicardial vein branch and is thus maximally distant from the right ventricular lead located in the right apex. (Fig.1). By appropriate programming with an intrinsically unphysiologically short AV conduction time, both ventricles can subsequently be depolarized in a purely technical manner.

The original guidelines for CRT were shaped by the inclusion criteria of larger trials such as COMPANION [1] (patients with an LVEF <35%, a QRS width of >120 ms, and NYHA stage III) or CARE-HF [2] (slightly different QRS width and additional echo criteria). In CARE-HF, both the primary end point (death or hospitalization for heart failure) and the secondary end point of mortality alone were reduced by nearly 35% in relative terms (16% and 7%, respectively, in absolute terms). Because only CRT-P had been implanted, the mortality benefit was achieved by fewer patients entering terminal heart failure.

Subsequent studies focused on markedly symptomatic patients (stage III/IV) with a narrow QRS complex (RethinQ) and on more oligosymptomatic patients with a more narrow QRS complex (Echo-CRT) [3,4]. Unfortunately, both studies failed to show CRT benefit; in fact, Echo-CRT demonstrated excess mortality with CRT. The largest CRT trial, MADIT-CRT, included patients with stage NYHA I and II who had an LVEF of <30% and a QRS width of >130 ms [5]. Long-term follow-up over a mean of 5.6 years showed a relative mortality reduction of 41% in the CRT-D group compared with the ICD-only group. With regard to a heart failure event, the relative reduction was as high as 62%.

The detailed assessment of all studies and especially of subgroup analyses led to a differentiated assessment of when CRT can be effectively indicated.

Whereas in the past only the QRS width was relevant, today the exact QRS morphology is also considered important. Patients with a typical left bundle branch block (according to the definition of D. Strauss: QS or rS in V1, a “slurring” best visible in V5, QRS width >140 ms in man resp. >130 ms in woman [6]) benefited massively in MADIT-CRT, whereas patients with a right bundle branch block or a non-specific block did not benefit at all. In addition, other subgroup analyses also showed that patients with long-standing permanent right ventricular pacing benefit little from an upgrade.

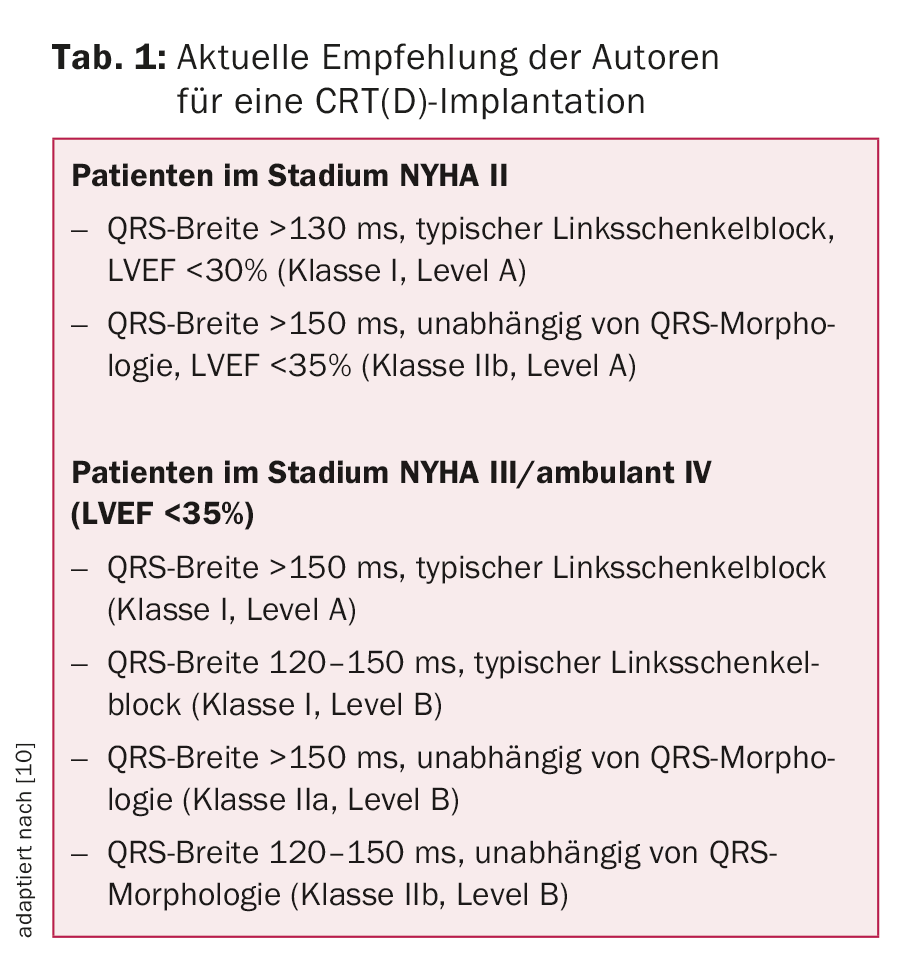

The current 2015 indications are shown in Table 1. In general, CRT should only be considered if optimal medical therapy has already been established for at least three months and the presumed life expectancy is at least one year.

Factors for a response

Unfortunately, all randomized trials so far have not really succeeded in achieving even better selection of future responders (i.e., response to CRT). In the PROSPECT study, various echocardiographic dyssynchrony parameters were investigated [7]. Because of the low sensitivity and specificity of each individual and also certain combined echo-parameters, it is believed that echocardiography is not suitable at this time to predict a responder with sufficient certainty. This means that echocardiography has no value in patient selection in clinical practice, except for the determination of EF.

Factors that are relevant to response but cannot be influenced are female sex and nonischemic cardiomyopathy-and, from a technical point of view, avoiding placement of the coronary sinus probe in an apical position. If the coronary sinus electrode cannot be placed in a favorable location for anatomic reasons (scar region, threshold problems, or simultaneous diaphragmatic pacing) or if selfconduction is too rapid, as in atrial fibrillation, and thus complete resynchronization is not possible, patients also do not respond to CRT. Extracardiac factors such as obesity, COPD, or PAVD may preclude improvement in NYHA class despite echocardiographic response.

Whether patients with impaired LV function who, because of higher-grade AV block, are likely to be significantly or always paced in the right ventricle during follow-up should receive a CRT system was investigated in the Block HF trial [8]. It was shown that there was a significant reduction in the combined end point of heart failure hospitalization, death, or at least a 15% increase in an echocardiographically determined LV volume index in the CRT group. However, the quality of the study is limited by the mix of end points and of pacemaker/ICD patients and the unclear definition of “impaired LV function.” We recommend CRT implantation to a patient if his LV function is below 45-50%.

Special aspects of CRT in elderly patients

Currently, the mean age of the approximately 5000 patients who receive a pacemaker in Switzerland each year is 77 years; the mean age of the approximately 1200 ICD patients is 64 years. While only 4% of all pacemaker patients receive CRT, the proportion of ICD patients is already 33%. According to the Swiss mortality tables, the mean life expectancy of male pacemaker patients is ten years, of female patients twelve years.

Although patients with symptomatic heart failure certainly have a shorter life expectancy than the overall population, life expectancy should be the primary consideration in deciding whether to use CRT with defibrillator backup (CRT-D). It is important to explain to the patient that the use of the CRT pacemaker, when properly indicated, offers a good chance of improving symptoms. This is a primary concern for many patients, not least because the number of comorbidities is often not insignificant and increases with age. CRT per se has also shown mortality reduction.

Compared with the CRT pacemaker, the CRT-D is more expensive and causes more potentially distressing complications such as unwarranted shock therapy, infection, and electrode complications. It must be explained to the patient that sudden cardiac death (which is sometimes desired) is prevented by the CRT-D (tab. 2) . The possible deactivation of the defibrillator function at the patient’s request must also be mentioned. Incidentally, the same applies to the pacemaker function, although the patient must then be aware that the remaining quality of life may decrease significantly. In an American study of elderly patients who received CRT-D at a mean age of 83 years, 10% had died after one year, 21% after two years, and half after 3.6 years [9].

In Switzerland, about twice as many patients currently receive a CRT-D than a CRT-P. In light of the above figures, the use of CRT without defibrillator function should be seriously considered and discussed with the patient. In addition, there are numerous comorbidity indices that are helpful in predicting whether the patient will die from something other than sudden cardiac death. Strong predictors of death without prior ICD therapy include terminal renal failure or malignancies.

Conclusion

CRT is also a very effective therapy for improving heart failure symptoms in elderly patients when properly indicated. Especially in old age, such symptomatic improvement is often the main concern of patients. The elderly patient must therefore be made aware that a CRT-D can prevent sudden cardiac death. Once a decision has been made to use a CRT-D, the patient and family should be informed that the defibrillator function can be deactivated at any time, and efforts should be made to document this in an advance directive.

Literature:

- Bristow MR, et al: Cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2140-2150.

- Cleland JGF, et al: The Effect of Cardiac Resynchronization on Morbidity and Mortality in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1539-1549.

- Beshai JF, et al: Cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure with narrow QRS complexes. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 2461-2471.

- Ruschitzka F, et al: Cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure with a narrow QRS complex. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1395-1405.

- Goldenberg I, et al: Survival with Cardiac-Resynchronization Therapy in Mild Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1694-1701.

- Strauss DG, et al: Defining left bundle branch block in the era of cardiac resynchronization therapy. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107: 927-934.

- Chung ES, et al: Results of the Predictors of Response to CRT (PROSPECT) trial. Circulation 2008; 117: 2608-2616.

- Curtis AC, et al: Biventricular Pacing for Atrioventricular Block and Systolic Dysfunction N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1585-1593.

- Rickard J, et al: Survival in octogenarians undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy compared to the general population. PACE 2014; 37: 740-744.

- Priori SG, et al: 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 2793-2867.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(3): 15-17