Typical pain symptoms or blood in the urine often indicate a stone disease. There are many possible causes. Imaging procedures such as sonography or computer tomography can be used to detect bladder or urethral stones.

Some of the concretions in the bladder may originate from the kidneys. The primary site of origin is the urinary bladder itself, especially in cases of bladder emptying disorders [1]. Men are more frequently affected than women.

In developing countries, malnutrition is a common cause of the primary formation of urinary bladder stones [2]. Dehydration favors the formation of stones. In Western countries, secondary bladder stones are the most common type and account for around 5% of all urolithiasis. Urinary stasis, recurrent urinary tract infections, foreign bodies and intestinal mucosa in the urinary tract are risk factors for calculus formation. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or neurogenic bladder emptying disorders with the formation of residual urine are the most common causes of cystolithiasis, accounting for around 75%. Urinary tract infections and long-term catheterization can provoke bladder stones. For example, patients with spinal cord injuries and permanent catheterization have a 9-fold increased risk of concrement formation in the urinary bladder [4,5].

The symptoms of cystolithiasis are often characterized by recurrent cystitis, dysuria, alguria, pollakiuria and interrupted urine flow or urinary retention. Small concretions may be asymptomatic. Colic and hematuria are typical with larger stones [3]. Accompanying nausea and vomiting can be a result of the pain.

Without further prophylaxis, recurrences of stone formation often occur. Foods containing oxalic acid should be avoided. Drinking plenty of fluids and exercising is helpful.

As with nephrolithiasis, therapeutic options include ESWL, percutaneous lithotripsy or section alta, depending on the size and number of stones. Spontaneous discharge of small calculi is possible [1]. If there is evidence of urosepsis as a result of cystolithiasis, surgical treatment is the primary therapy.

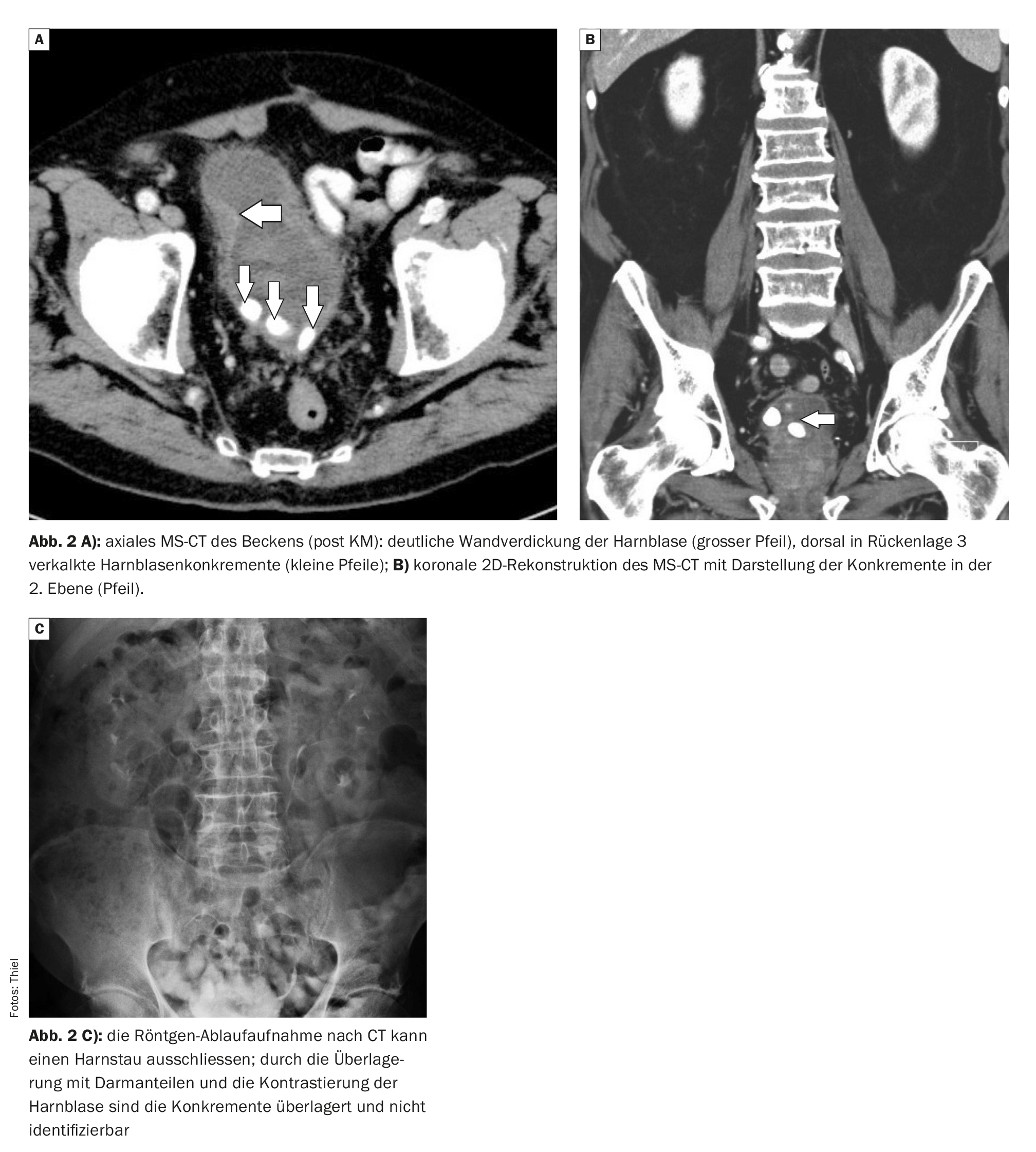

X-ray detection of bladder stones is made more difficult by overlapping with intestinal air and contents.

Sonographically, the bladder concretions show a bright reflex. If the bladder is completely full, small concrements can also be detected [5]. Depending on the size of the stone, a dorsal acoustic shadow may also be visible. The mobility of the stones can be checked by repositioning the patient.

Calcified concretions can be detected very well by computer tomography and their size can be determined precisely.

Concrement detection can be problematic with magnetic resonance imaging. Small calcified concretions can be masked in the absence of a signal, larger ones can be demarcated. The high soft tissue contrast enables the visualization of accompanying inflammatory changes in the bladder wall.

Case studies

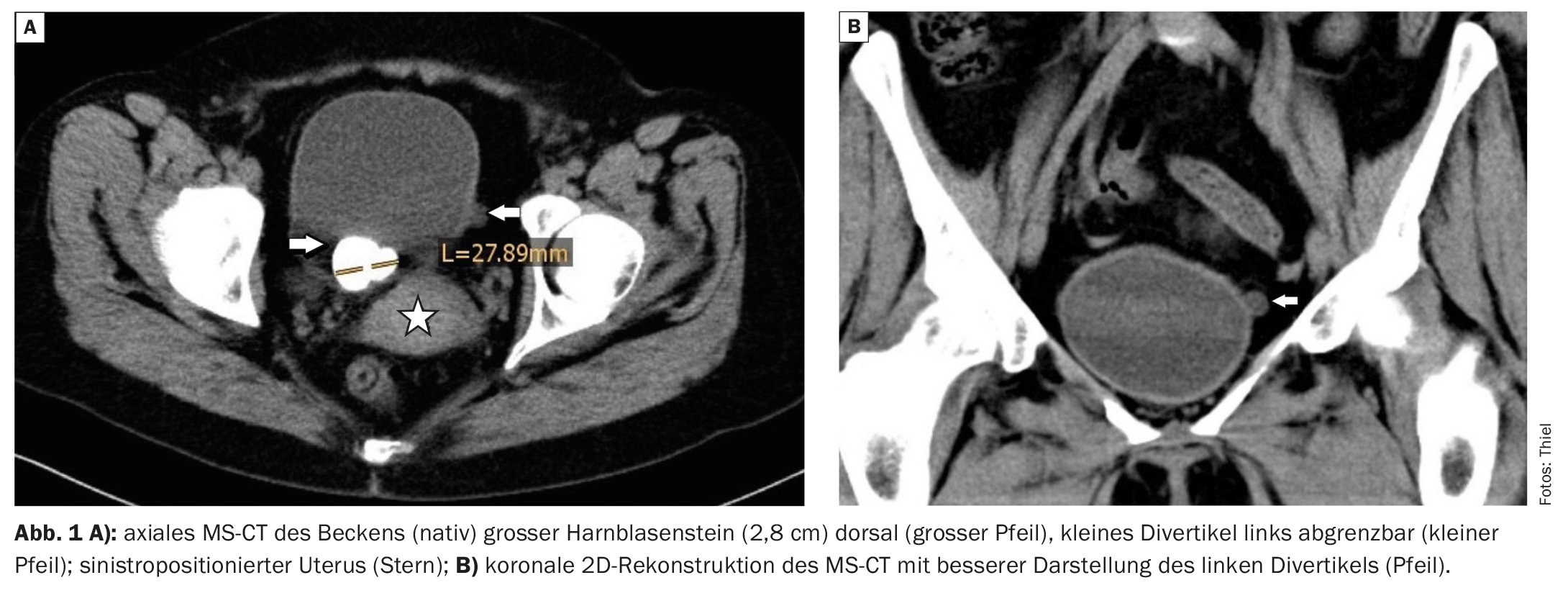

In case example 1 (Fig. 1A to C), a 47-year-old female patient complained of persistent pain when urinating and urinary bladder emptying disorders. Occasionally there was also alguria. CT showed a large calcified concrement of the bladder and diverticula on both sides.

Case 2 (Fig. 2A and B) shows a circular wall thickening of the urinary bladder in an 84-year-old patient with considerable prostatic hypertrophy (6 cm in diameter), which may be due to inflammation or may be the result of reactive muscular hypertrophy of the bladder wall during voiding dysfunction. The CT scan revealed three calcified intravesical concretions, primarily secondary to the obstructed bladder emptying.

Take-Home-Messages

- Urinary bladder stones occur more frequently in men than in women.

- A distinction is made between primary and secondary formation of intravesical calculi.

- Small bladder stones can be asymptomatic, but larger ones can cause considerable discomfort with pain, micturition disorders, urinary retention and urosepsis.

- Depending on the size of the stones and the clinical picture, ESWL, minimally invasive and surgical treatments may be necessary.

- Imaging evidence is primarily obtained by sonography or computer tomography.

Literature:

- Seitz KH, et al: Clinical sonography and sonographic differential diagnosis. 2008. DOI: 10.1055/b-0034-80159

- Manski D: Urinary bladder stones: causes, diagnosis and therapy, www.urologielehrbuch.de/harnblasensteine.html,(last accessed 23.10.2023)

- Matzik S: Bladder stones: causes, symptoms, treatment.

www.netdoktor.de/krankheiten/blasensteine,(last accessed 10/23/2023) - Schwartz BF, Stoller ML: The vesical calculus. Urol Clin Noth Am 2000; 27: 333-346.

- Becht EW, Hutschenreiter G, Klose K (eds.): Urologische Diagnostik mit bildgebenden Verfahren. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York: 1988: pp. 123.

FAMILY PHYSICIAN PRACTICE 2023; 18(11): 50-51

Cover picture: Nevit Dilmen, Wikipedia