Cat scratch disease KKK is a self-limiting infection with regional lymphadenopathy. The causative agent is usually Bartonella henselae, and transmission occurs through cat scratches or bites. Diagnosis is based on typical clinic in feline exposure and serology. If the clinic is atypical, PCR analysis and histology may be helpful. In mild clinc, the spontaneous course can be awaited; in severe courses, azithromycin is recommended for 5 days.

Medical history

A 60-year-old female patient presents with a tumor of unclear etiology on the left medial humerus. She reports a moped accident in Bali six weeks earlier, sustaining abrasions to her knee and a right clavicle fracture. A few weeks later, she noticed a stitch-like skin lesion on her left upper arm and, for the past two weeks, an additional progressive solitary hyperthermic swelling. Fever, chills, or other symptoms are denied. However, she said she has noticed a weight loss of 1.5 kg in recent weeks. The patient suffers from insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, lives several months a year in Bali and owns several cats in Switzerland. Allergies are negated.

Findings: The patient is cardiopulmonarily compensated, afebrile and in good general condition with truncal obesity. On the distal left medial upper arm, there is a pressure painful dermal 5×7 cm measuring, reddened, hyperthermic and fluctuant soft tissue swelling with axillary lymphadenopathy. The rest of the internal examination is unremarkable.

Laboratory chemistry reveals CRP elevation to 71 mg/l (norm <5), leukocytosis at 14×10S9/l, and mild eosinophilia at 0.36×10S9/l.

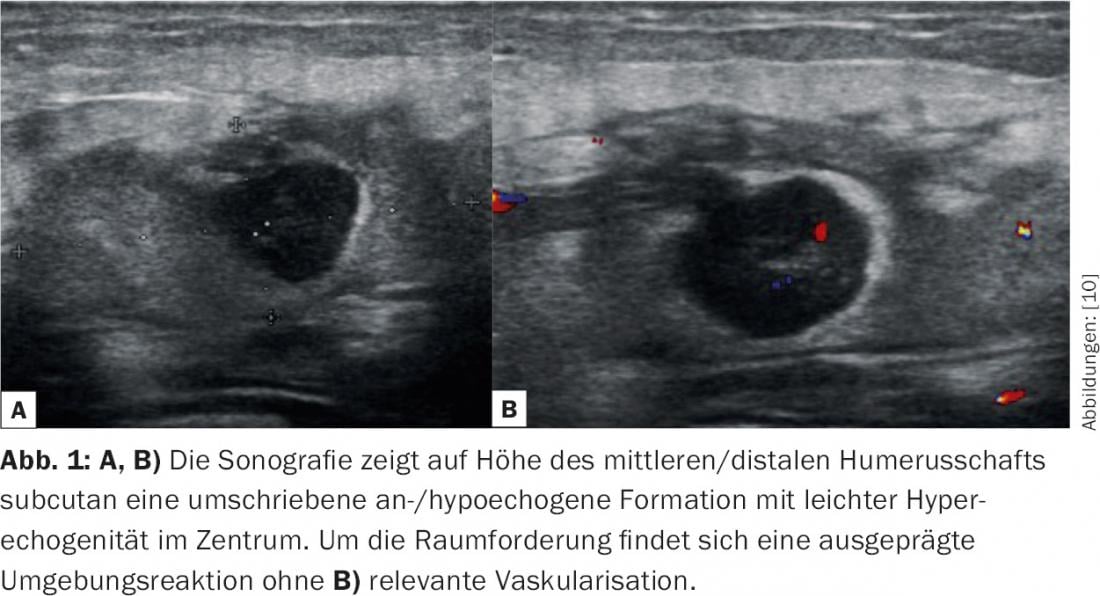

Sonographically, a solitary cystic structure of 1.6×1.2 cm in size can be visualized in the subfascial inner humerus with hyperechogenic marginal zone and hypoechogenic surrounding tissue (Fig. 1).

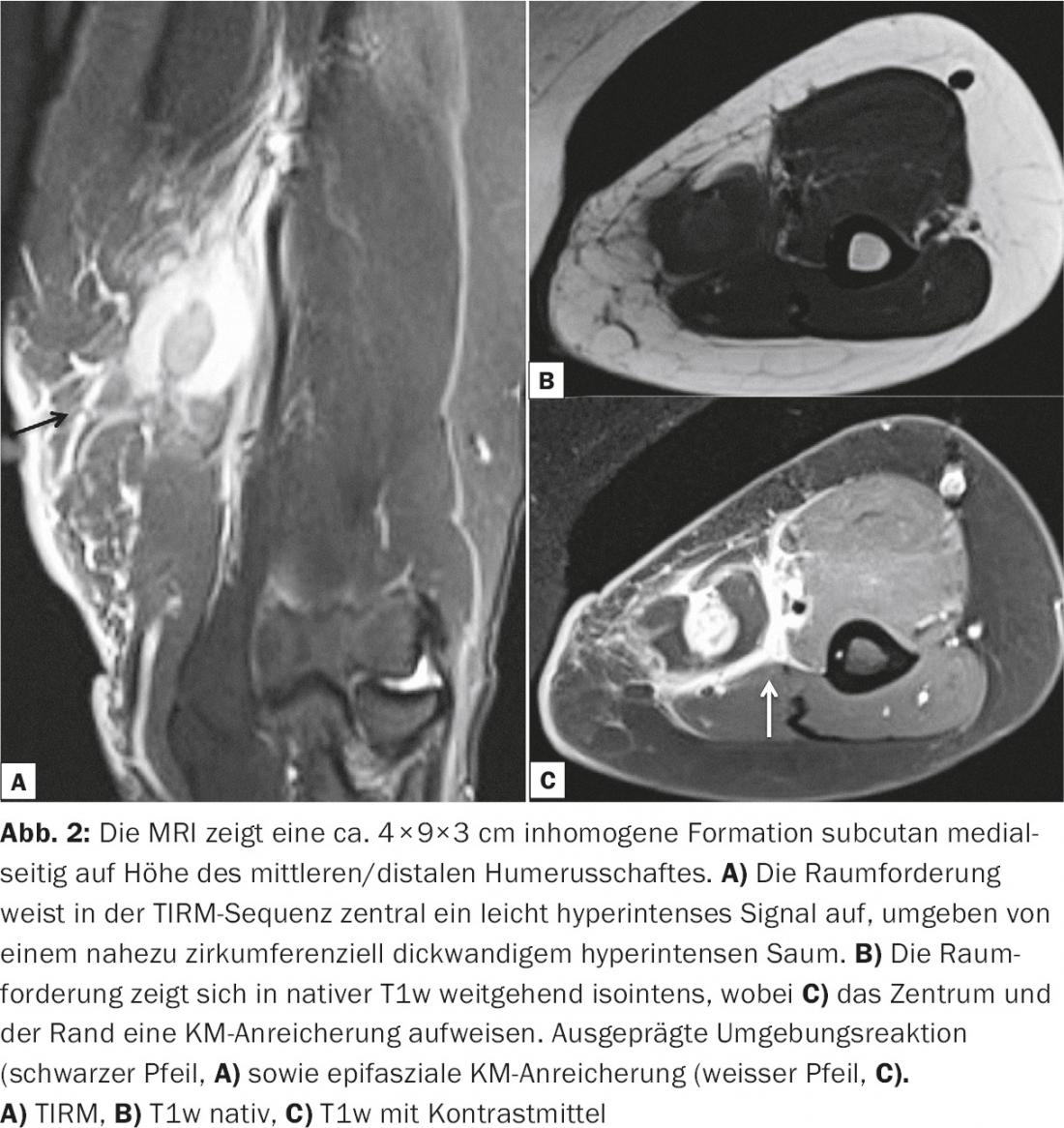

MRI confirms subcutaneously an inhomogeneous, partially KM-affine mass (Fig. 2).

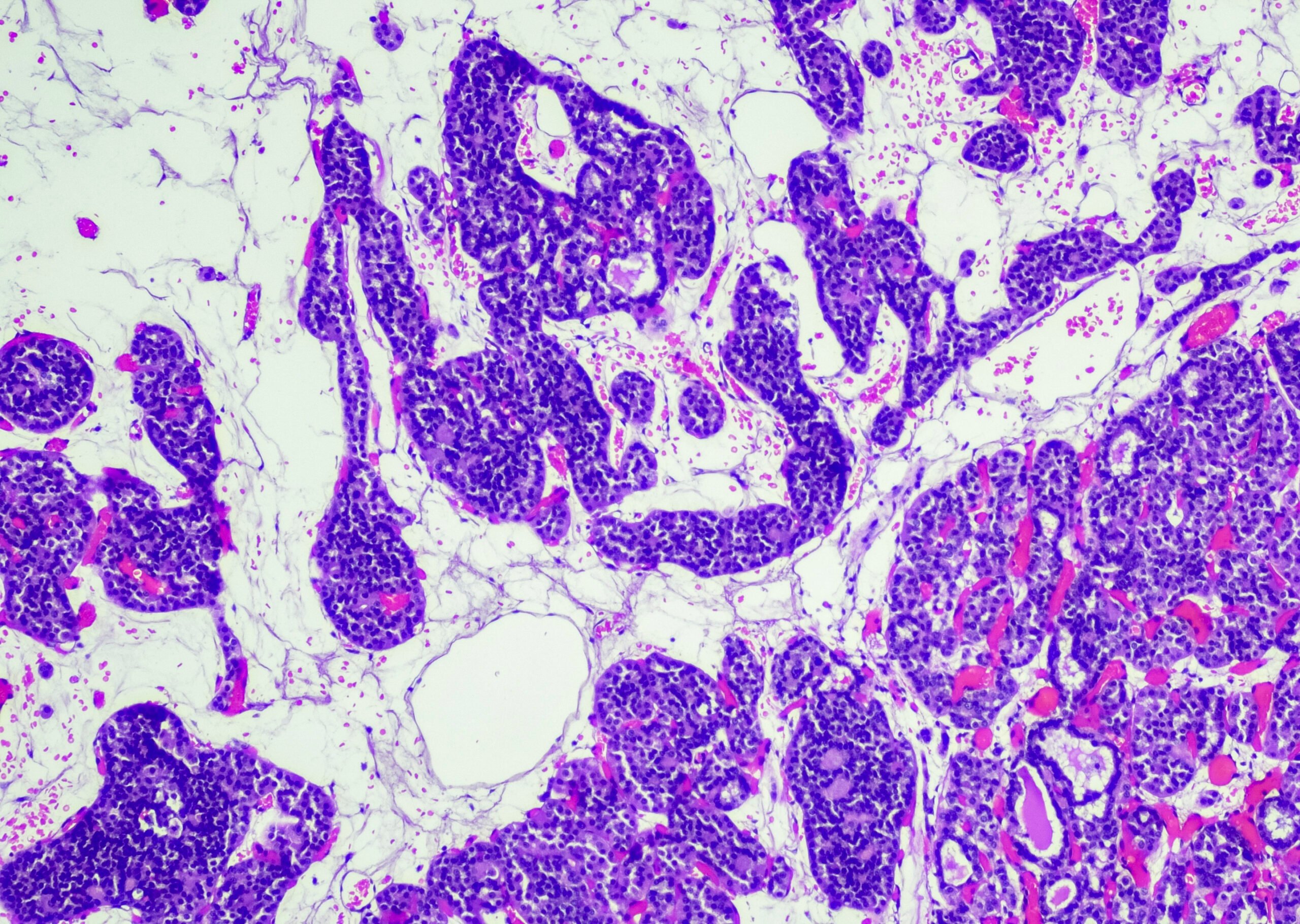

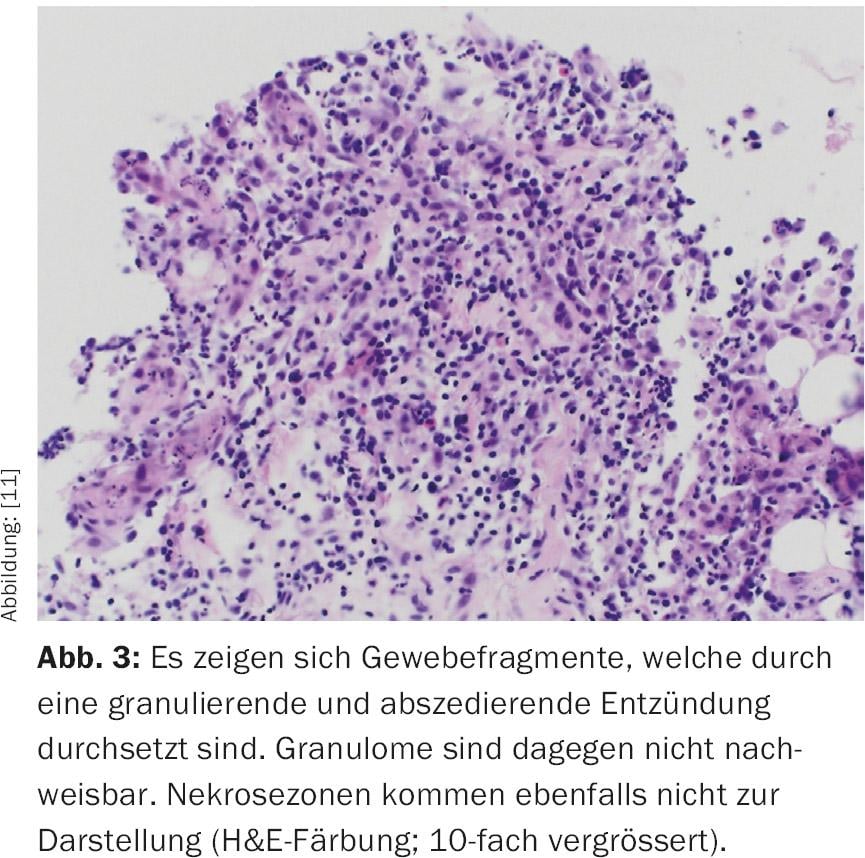

In case of unclear cause and possible tropical parasitosis after the accident in Bali, invasive diagnostics by fine needle aspiration follows. Cytologically, there is evidence of an abscess without evidence of pathogens. In case of progressive pain and increasing local findings, abscess splitting is performed, emptying 10 ml pus. Histologically, there is a florid inflammation with numerous neutrophil granulocytes; necrotizing granulomas cannot be detected. Gram and Whartin-Starry stains fail to detect pathogens (Fig. 3).

Cultures from the fine-needle biopsy and specimens from the abscess show no growth. Therefore, a eubacterial PCR is performed in which Bartonella henselae can be detected. Subsequently requested serology for B. henselae IgG reveals a reactive value of 1:>256.

Diagnosis

It is an abscessing inflammation in cat scratch disease.

Therapy and course

Stop antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 2.2 g. Due to the protracted course, oral therapy with azithromycin 1× 500 mg on day 1 and 1× 250 mg from day 2-5 is recommended. Day initiated.

Within a week, the local finding has clearly regressed and healed after two months.

Discussion

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is a zoonosis caused by Bartonella henselae . The pathogen is a gram-negative aerobic, facultative intracellular rod. B. henselae is endemic worldwide. The main reservoir is young domestic cats [2], which are often clinically healthy but may still show persistent bacteremia [9]. Infection usually occurs through scratches and bite wounds. KKK is characterized by a usually self-limiting, regional lymphadenopathy.

Pathogenetically, a local infection develops in the host organism after inoculation, which manifests as regional lymphadenopathy. In addition, endothelin invasion and occasional bacteremia may occur [1]. Dissemination is observed mainly in patients after organ transplantation and in HIV disease [4].

Clinically, usually three to ten days after a cat scratch or bite injury, a symptomless papular or pustular skin lesion appears at the inoculation site, typically persisting for one to three weeks and healing without scarring. Regional lymphadenopathy occurs in the course. This is the main feature of KKK, is seen in 85% of patients and persists for two to four months [6]. In addition, mild fever and malaise often occur. Generalized lymphadenopathy is rare. Involvement of visceral organs with appearance of granulomas in liver or spleen is seen mainly in children. Atypical manifestations include conjunctivitis, atypical pneumonitis, and prolonged fever [2,3,6,8].

In immunosuppressed patients (e.g., HIV patients), bacillary angiomatosis and peliosis hepatis occur as severe forms of progression [4,6]. Bacillary angiomatosis is characterized by vascular neoproliferates in the skin, lymph nodes, and visceral organs; peliosis is characterized by blood-filled cysts in the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes.

Diagnostically, a history of cat contact and subsequent onset of lymphadenopathy is suggestive. Serologic, microbiologic, and histologic examinations may be used for confirmation [2], and a combination of matching findings will confirm the diagnosis. With a typical history and clinic, a Bartonella titer of ≥1:64 and a positive IgM – usually detectable only briefly – may be used to confirm the diagnosis. In case of atypical findings, histological processing of a tissue sample with additional Whartin Starry staining as well as PCR and culture for Bartonella may be helpful [3]. Unfortunately, both serology, PCR, and culture of the fastidious bacterium are not very sensitive [5,6,7], and histologic findings demonstrating acellular necrosis surrounded by multiple layers of histiocytes and epithelioid cells are not specific. Thus, diagnosis of acute disease can be difficult.

Infectious and malignant causes must be considered in the differential diagnosis of unclear lymphadenopathy. The most common infectious agents are Staphylococcus aureus and group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. The viral pathogens in question are HIV, CMV, and EBV in particular. In addition, mycobacteria as well as toxoplasmosis should be sought. If there is an additional skin lesion, differential diagnosis should consider pathogens such as Francisella tularensis, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, and Bacillus anthracis. In the case of malignancies, lymphomas are in the foreground. Rarely, systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis are found as the cause.

The therapy of a cat scratch disease depends on the patient and the extent of the disease: In immunocompetent patients with mild to moderate disease, antibiotics may not be necessary, since healing occurs slowly even without therapy [5,8]. For extensive infestation, azithromycin 500 mg on the first day, followed by 250 mg for an additional four days, is recommended [10]. In addition, aspiration or surgical excision may be performed for abscessed lymph nodes. Therapy of immunocompromised patients or patients with disseminated disease should be left to specialists.

Literature:

- Dehio C: Molecular and cellular basis of bartonella pathogenesis.Annu Rev Microbiol 2004; 58: 365.

- Florin TA, et al: Beyond cat scratch disease: widening spectrum of Bartonella henselae infection.Pediatrics 2008; 121(5): 1413.

- Margileth AM: Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment of Cat Scratch Disease. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2000; 2(2): 141.

- Mosepele M, et al: Bartonella infection in immunocompromised hosts: immunology of vascular infection and vasoproliferation. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012; 612809: 1-5.

- Rolain JM, et al: Recommendations for treatment of human infections caused by Bartonella species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004; 48(6): 1921.

- Velho PE, et al: What do we (not) know about the human bartonelloses? Braz J Infect Dis. 2003; Feb; 7(1): 1-6.

- Vermeulen MJ, et al: Low sensitivity of Bartonella henselae PCR in serum samples of patients with cat-scratch disease lymphadenitis. J Med Microbiol. 2008; 57(Pt 8): 1049.

- Windsor JJ: Cat-scratch disease: epidemiology, aetiology and treatment.Br J Biomed Sci 2001; 58(2): 101.

- Demers DM, Bass JW, Vincent JM et al: Cat-scratch disease in Hawaii: etiology and seroepidemiology. J Pediatr. 1995 Jul; 127(1): 23-6.

- Radiology University Hospital Basel, with kind permission of Dr. Garcia Alzamora Meritxell, Stv. Senior Physician Musculoskeletal Diagnostics, University Hospital Basel, Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine.

- Pathology University Hospital Basel, with kind permission of PD Dr. med. Ellen Christina Obermann, Head Physician, University Hospital Basel, Pathology.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(11): 38-41